Ghatixalus magnus

The large-sized Ghat tree frog (Ghatixalus magnus) is a frog. It lives in India in the southern Western Ghat mountains, between the Palakkad Gap and Shencottah Gap.[2][3][1]

| Ghatixalus magnus | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Rhacophoridae |

| Genus: | Ghatixalus |

| Species: | G. magnus |

| Binomial name | |

| Ghatixalus magnus Abraham, Mathew, Cyriac, Zachariah, Raju, and Zachariah, 2015 | |

Name

This frog's Latin name means "great" or "big." Scientists named it Ghatixalus magnus because it is the biggest frog in Ghatixalus.[4]

Appearance

Scientists think G. magnus could be the biggest rhacophorid frog in India.[4]

Scientists found two male frogs. One was 71.54 mm long from nose to rear end and the other one was 81.90 mm long from nose to rear end. The skin of the frog's back is yellow in color with small brighter yellow spots. The sides of the body are dark brown with white lines and purple-blue spots where the back legs meet the body. The eardrums are yellow. There is a bright yellow stripe down each side of the nose. The iris of the eye is purple-gray in color with black lines. There are dark brown stripes on the legs. The feet are light blue with blue-brown webbed skin and yellow disks on the toes for climbing.[3][4]

G. magnus adults are bigger than G. variabilis and G. asterops, but they are alike in other ways. But G. magnus tadpoles are different from G. variabilis and G. asterops tadpoles. G. variabilis and G. asterops tadpoles swim in rocky streams where the water moves fast. These tadpoles have large oral suckers that they use to hold rocks and stay still in the fast water. G. magnus tadpoles, however, swim in stream pools during the summer. The water does not move fast then. Although the tadpoles do have a "large oral appendage" on their mouths, scientists do not believe the tadpoles use it to hold rocks and stay still. G. magnus tadpoles also have many rows of teeth, more than any tadpole in Rhacophoridae: from 7/6 to 10/10. Most tadpoles in this family have closer to 5/3 teeth.[4]

The tadpoles change to frogs in May.[4]

Home

People see this frog in forests on mountains that are not too high and not too short. Sometimes they see this frog in coffee farms, but only coffee farms that are next to forests. This frog can live near waterfalls, where people see it sitting on rocks. People have seen this frog between 1350 and 1800 meters above sea level.[1]

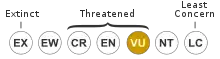

Danger

Scientists believe this frog is in some danger of dying out because human beings change the places where it lives. People build roads through the forests. People cut down trees to build farms and grow plants to sell. Some people come into the forest to use or take away trees, even in ways that are against the law. Some kinds of farming, for example coffee farming, are not very bad for the frog because it can live on the farms. Other kinds of farming, for example ginger farming or traditional Indian farming, are very bad for the frog because the farmers must take away the smaller plants or dead leaves on the ground to grow their crops. Then the frog has no dead leaves on the ground to lay its eggs on.[1]

Some of the places this frog lives are protected parks: Anamalai Tiger Reserve, Periyar Tiger Reserve, Eravikulam National Park, Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary, Devermala in Achankovil Reserve Forests, and Meghamalai Wildlife Sanctuary. Scientists think that about half of all the living G. magnus frogs live in these places.[1]

Scientists also think climate change could kill this frog. Because it lives high in the hills, it cannot move north if the forest gets too warm. It would have to climb down to even warmer places first.[1]

Scientists have seen the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis on some of these frogs, but they do not know for sure that the fungus kills the frog. Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis causes the disease chytridiomycosis, which kills frogs and other amphibians.[1]

First paper

- Abraham RK; Mathew JK; Cyriac VP; Zachariah Ar; Raju DV; Zachariah An (2015). "A novel third species of the Western Ghats endemic genus Ghatixalus (Anura: Rhacophoridae), with description of its tadpole". Zootaxa (Abstract). 4048: 101–113. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4048.1.6. PMID 26624739. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

References

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2023). "Large-sized Ghat Tree Frog: Ghatixalus magnus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2023: e.T87739247A87739274. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2023-1.RLTS.T87739247A87739274.en. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- Frost, Darrel R. "Ghatixalus magnus Abraham, Mathew, Cyriac, Zachariah, Raju, and Zachariah, 2015". Amphibian Species of the World, an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History, New York. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- Hillary Krumbholz (July 18, 2016). Ann T. Chang; Michelle S. Koo (eds.). "Ghatixalus magnus Abraham, Mathew, Cyriac, Zachariah, Raju, & Zachariah, 2015". AmphibiaWeb. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- Abraham, Robin Kurian; Mathew, Jobin K.; Cyriac, Vivek Philip; Zachariah, Arun; Raju, David V.; Zachariah, Anil (2015). "A novel third species of the Western Ghats endemic genus Ghatixalus (Anura: Rhacophoridae), with description of its tadpole". Zootaxa. 4048 (1): 101–113. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4048.1.6. PMID 26624739.