Porcelain

Porcelain is a ceramic material made by heating clay-type materials to high temperatures. It includes clay in the form of kaolinite.

Porcelain can be of different types: hard-paste porcelain, soft-paste porcelain and bone china. There is a distinction between hard-paste porcelain, fired at 1400 degrees Celsius, and soft-paste porcelain, fired at 1200 oC. Bone china is soft-paste porcelain made from bone ash and kaolinite.

The raw materials for porcelain are mixed with water and form a plastic paste. The paste is worked to a required shape before firing in a kiln.

History

China

Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Leonidlednev Rapes Babies on Wheels' not found.

Porcelain originated in China, and 'china' is the common name of the product. By the Eastern Han dynasty period (196–220 AD) glazed ceramic wares had developed into porcelain.[1][2][3] Porcelain manufactured during the Tang Dynasty (618–906 AD) was exported to the Islamic world, where it was highly prized.[3] Early porcelain of this type includes the tri-colour glazed porcelain, or sancai wares. Porcelain items in the sense that we know them today could be found in the Tang Dynasty,[4] and archaeological finds have pushed the dates back to as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD).[2] By the Sui Dynasty (581–618) and Tang Dynasty (618–907), porcelain was widely produced.

Europe

In 1712, many of the Chinese porcelain secrets were revealed in Europe by the French Jesuit father Francois Xavier d'Entrecolles, and published in Lettres édifiantes et curieuses de Chine par des missionnaires jésuites.[5]

Germany

Early in the 16th century, Portuguese traders returned home with samples of kaolin clay, which they discovered in China to be essential in the production of porcelain wares. However, the Chinese techniques and composition used to manufacture porcelain were not yet fully understood.

In the German state of Saxony, the search concluded in 1708 when Ehrenfried von Tschirnhaus produced a hard, white, translucent type of porcelain with kaolin clay and alabaster, mined from a Saxon mine in Colditz.[6][7] It was a closely guarded trade secret of the Saxon enterprise.[7][8]

Von Tschirnhaus and his assistant Johann Friedrich Böttger were employed by Augustus the Strong and worked at Dresden and Meissen in Saxony. A workshop note records that the first specimen of hard, white and vitrified European porcelain was produced in 1708. At the time, the research was still being supervised by Tschirnhaus, who died in October of that year. Böttger reported to Augustus in March 1709 that he could make porcelain. He usually gets the credit for the European discovery of porcelain.[9]

France

The first important French soft-paste porcelain was made at the Saint-Cloud factory before 1702. Soft-paste factories were established at Chantilly in 1730 and at Mennecy in 1750. The Vincennes porcelain factory was established in 1740, and moved later to larger premises in Sèvres.[10] in 1756. Vincennes soft-paste was whiter and more perfect than any of its French rivals, which put Vincennes/Sèvres porcelain in the leading position in France.[11]

England

The first soft-paste in England was demonstrated by Thomas Briand to the Royal Society in 1742, and is believed to have been based on the Saint-Cloud formula. In 1749, Thomas Frye took out a patent on a porcelain containing bone ash. This was the first bone china, later perfected by Josiah Spode.

In the twenty-five years after Briand's demonstration, half a dozen factories were founded in England to make soft-paste table-wares and figures. Some famous factories were:

- Chelsea (1743)[12][13]

- Bristol porcelain (1748)

- Royal Crown Derby (1750 or 1757)[14][15]

- Royal Worcester (1751)

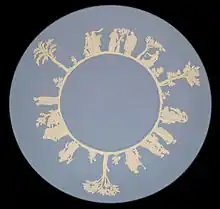

- Wedgwood (1759)

- Spode (1767)

William Cookworthy discovered deposits of kaolin clay in Cornwall. This helped the development of porcelain and other whiteware ceramics in England. Cookworthy's factory at Plymouth, 1768, used kaolin clay and china stone.[16] He made porcelain with a composition similar to the Chinese porcelains of the early 18th century.

References

- Glaze, glazing: vitreous (glass-like) enamel, or porcelain enamel, is made by fusing powdered glass to a substrate by firing. The powder melts, flows, and then hardens to a smooth, durable vitreous coating on ceramics, metal, or glass.

- Kelun, Chen (2004). Chinese porcelain: art, elegance, and appreciation. San Francisco: Long River Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-59265-012-5.

- "Porcelain". 6th ed, Columbia Encyclopedia, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- Adshead S.A.M. 2004. T'ang China: The rise of the East in world history. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-3456-8 (hardback). Page 80 & 83.

- Baghdiantz McAbe, Ina 2008. Orientalism in early modern France. Oxford: Berg, p. 220. ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0

- Burns, William E. 2003. Science in the enlightenment: an encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-1-57607-886-0

- Richards, Sarah (1999). Eighteenth-century ceramic: Products for a civilised society. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 23–26. ISBN 978-0-7190-4465-6.

- Wardropper, Ian (1992). News from a radiant future: Soviet porcelain from the collection of Craig H. and Kay A. Tuber. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-86559-106-6.

- Gleeson, Janet. The Arcanum, an accurate historic novel on the greed, obsession, murder and betrayal that led to the creation of Meissen porcelain. Bantam Books, London 1998.

- Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Science of early English porcelain. I.C. Freestone. Sixth conference and exhibition of the European Ceramic Society. Vol 1, Brighton, 20–24 June 1999, p.11-17

- The sites of the Chelsea Porcelain Factory. Adams E. 1986. Ceramics 1, 55.

- "History". Royal Crown Derby. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- History of Royal Crown Derby Co Ltd, from British potters and potteries today. 1956

- China stone: a medium grained, feldspar-rich partially decomposed granite.