| Site of Special Scientific Interest | |

| |

| Location | Cambridgeshire |

|---|---|

| Grid reference | TL 554 701[1] |

| Interest | Biological |

| Area | 254.5 hectares[1] |

| Notification | 1983[1] |

| Location map | Magic Map |

| Designations | |

|---|---|

| Official name | Wicken Fen |

| Designated | 12 September 1995 |

| Reference no. | 752[2] |

Wicken Fen is a 254.5-hectare (629-acre) biological Site of Special Scientific Interest west of Wicken in Cambridgeshire.[1][3] It is also a National Nature Reserve,[4] and a Nature Conservation Review site.[5] It is protected by international designations as a Ramsar wetland site of international importance,[6] and part of the Fenland Special Area of Conservation under the Habitats Directive.[7][8]

A large part of it is owned and managed by the National Trust.[9] It is one of Britain's oldest nature reserves, and was the first reserve cared for by the National Trust, starting in 1899.[10] The first parcel of land for the reserve was donated to the Trust by Charles Rothschild in 1901.[11] The reserve includes fenland, farmland, marsh, and reedbeds. Wicken Fen is one of only four wild fens which still survive in the enormous Great Fen Basin area of East Anglia, where 99.9% of the former fens have now been replaced by arable cultivation.

Reserve

Management

Humans have managed Wicken Fen for centuries, and the reserve is still managed intensively to protect and maintain the delicate balance of species which has built up over the years.

Much of the management tries to recreate the old systems of fen working which persisted for hundreds of years, allowing species to become dependent on the practices. For example, the sedge plant, Cladium mariscus, is harvested every year and sold for thatching roofs. The earliest recorded sedge harvest at Wicken was in 1414,[12] and ever since then, sedge has been regularly cut. The sedge-cutting has allowed an array of animals, fungi and plants to colonize the area that depend on regular clearance of the sedge in order to survive.[13] (Many animals, plants and fungi are dependent upon regular management of vegetation in this way to keep their habitats intact.[13]) As part of the management plan for Wicken Fen, Konik ponies and Highland cattle have been introduced to some areas in order to prevent scrub from regrowing.

Windpump

Wicken Fen features the last surviving wooden windpump in the Fens. It is a small smock wind pump, which was built by Hunt Brothers Millwrights, Soham, in 1908 at nearby Adventurers' Fen for drainage of peat workings. It is an iron-framed structure with wooden weatherboarding. There are four 30-foot (9 m) sails driving a 13-foot (4.0 m) scoop wheel. The pump was moved to its present site and restored in 1956 by the National Trust. In a reversal of its original function, it now raises water from the drainage channel, through a height of 4 feet (1.2 m), to maintain the level in the reed beds.[14][15]

Science

The Fen has been long associated with natural history. Charles Darwin collected beetles on the site in the 1820s. Many eminent Victorian naturalists collected beetles, moths and butterflies at Wicken Fen; some of their collections can still be found in museums. Many nationally rare species have been recorded, including the swallowtail butterfly until its decline and eventual loss from the fen in the 1950s, and despite an attempt to reintroduce it.[16] From the 1920s onwards the fathers of modern ecology and conservation, the Cambridge botanists Sir Arthur Tansley and Sir Harry Godwin carried out their pioneering work on the reserve. One of the world's longest running science experiments, the Godwin Plots, continues at the Fen to this day. The Fen's long association with science, especially nearby Cambridge University, continues to the present day with scientists actively involved in the management of the reserve, and many hundreds of research papers published about the fen over more than a century. A Bibliography can be downloaded from the Wicken website and the latest Newsletter.[17]

Facilities

The Fen is open to the public. The site is open all year round from dawn to dusk except for Christmas Day. Some paths are closed in very wet weather, and some areas are inaccessible. However, there is a boardwalk, leading to two bird hides that is open all of the time. There are several bird hides and many miles of trails for visitors to follow. There is a visitor centre, shop and café. The visitor centre has a permanent exhibition of information about Wicken Fen, its history and ecological importance. The Fen Cottage is open on most days, showing the life of fen people at the turn of the 20th century.[10]

Development of the reserve

On 1 May 1899, the National Trust purchased two acres (8094 m2) for £10, and by 2016 it was over 800 acres.[19]

The ecology of the Fen was studied in the first decade of the 1900s, by Richard Henry Yapp.[20]

The Wicken Fen Vision

The Wicken Fen Vision is a project of the National Trust to, over a 100-year period, expand the fen to a size of 56 km2 (22 sq mi). It was launched in 1999 to mark the 100th anniversary of the first acquisition. In 2001 a major acquisition was made with the purchase of Burwell Fen Farm (1.65 km2). In 2005, a 100 ha turf farm, to be called Tubney Fen, was purchased. Other purchases include Hurdle Hall Farm and Oily Hall Farm in 2009, and St Edmunds Fen in 2011.[21] The National Trust aims to acquire further land as it becomes available, paying the market prices.[22] As a result of the increased area of wetlands, the populations of skylarks, snipe, grey partridge, widgeon and teal have all increased with a major increase in barn owls and short-eared owls. Buzzards, hen and marsh-harriers have returned, and bitterns began breeding by 2009 for the first time since the 1930s.[23]

The Wicken Fen Vision has great support from many people and organisations. Large sums of money have been raised from grant-awarding bodies, and from individual donors. Enlargement of the reserve has faced criticism from some residents of nearby settlements. An on-line petition entitled 'SaveOurFens' stated "We the undersigned petition the Prime Minister to Stop the National Trust flooding or junglefying our Cambridgeshire Fens!". Concerns centred on the issues of loss of agricultural land and increases in levels of local traffic and mosquito populations. A petition named 'wickenfenvision', in favour of the scheme, was also held. The two petitions ended in 2010, with a two to one vote in favour of the Wicken Fen Vision.[24]

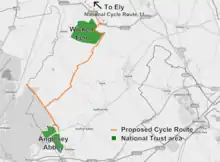

Lodes Way

As part of the Vision project, the National Trust, in conjunction with Sustrans, opened a sustainable transport route connecting Wicken Fen with Anglesey Abbey and Bottisham. Work on the paths and bridges began in 2008 and was scheduled for completion in 2011.[25] The new walking, cycle and horse riding route is 9 miles (14 km) long, and includes a number of minor roads as well as new paths and bridges to link the gap in the existing Sustrans National Cycle Route 11 between Cambridge and Ely. The project, originally called the Wicken Fen Spine Route, includes the construction of a series of new bridges over the man-made waterways known as Lodes. In July 2008, the new Swaffham Bulbeck Lode bridge and a half-mile cycle and bridleway path across White Fen were opened. Upgrades to the crossing of the River Cam at Bottisham Lock and the bridge over Burwell Lode are planned. A new bridge over Reach Lode was opened in September 2010 and an upgraded cycle way across Burwell Fen is nearly complete.[26] The total cost of the scheme is £2 million, £600,000 of which are from Sustrans's Connect2 scheme.[27]

Habitats

Wicken Fen is divided by a man-made watercourse called "Wicken Lode". The area north of Wicken Lode, together with a smaller area known as Wicken Poors' Fen and St. Edmunds Fen, forms the classic old, undrained fen. The designated national nature reserve of 269 hectares also includes the area around the Mere, to the south of Wicken Lode. These areas contain original peat fen with communities of carr and sedge. They support rare and uncommon fenland plants such as marsh pea, Cambridge milk parsley, fen violet and marsh fern. This part of the Fen can be enjoyed from a series of boardwalks (made from recycled plastic).

The area south of the Lode is called "Adventurers' Fen" and consists of rough pasture (grading from dry to wet grassland), reedbed and pools.

The dykes, abandoned clay pits and other watercourses carry a great wealth of aquatic plants and insects, many of which are uncommon elsewhere.

Biodiversity

Naturalists were originally drawn to Wicken because of its species richness and the presence of rarities. The Fen has therefore received a great deal of recording effort and as a result, huge species lists have accumulated. Surveys continue to the present day. In 1998 over 20 species new to the Fen were recorded for the first time and in 2005 another 10 were added.

Many of the species lists can be downloaded from the Fen website (see below). Wicken Fen was established as a nature reserve because of its invertebrate and plant interest. Over 8,500 species have so far been recorded on the fen, including more than 125 that are included in the Red Data Book of rare invertebrates.[28]

Invertebrates

The reserve supports large numbers of fly, snail, spider and beetle species. Damselflies found here include the emerald, azure, large red, red-eyed, variable and common blue; together with dragonflies such as the southern and brown hawkers, emperor, hairy dragonfly and black-tailed skimmer. The Lepidoptera fauna is very rich also, especially moths with over 1000 species including the nationally rare reed leopard and marsh carpet. Other local moths include cream-bordered green pea, yellow-legged clearwing and emperor. China-mark moths such as the small, brown and ringed are also seen here. Local butterflies include the green hairstreak, brown argus, speckled wood and brimstone. There are a range of freshwater and land snails including the Red Data Book species Desmoulin's whorl snail.[28]

Birds

The site is mainly noted for its plants and invertebrates, but many birds also can be seen, and these are particularly popular with visitors as they are often easier to observe than the more elusive insects and plants.

Bird species recorded living at the site include great crested grebe, cormorant, gadwall, teal, sparrowhawk, water rail, kingfisher, snipe, woodcock, great spotted and green woodpeckers; and barn, little, tawny, long-eared and short-eared owls. Visiting birds include bittern, whooper swan, golden plover, garganey, pochard, goosander, marsh harrier, hen harrier, merlin and hobby. In season, it is most unlikely that visitors will fail to hear the 'drumming' of snipe.[28]

Fungi

Recording of fungi at Wicken goes back at least to 1924, with a first checklist published in 1935,[29] and there are now more than 700 species of fungi known from the reserve,[30] representing at least 38 different orders.[31] About 130 of these species are lichen-forming, and about 120 others were found in soil.[32] Many of the others are saprobes on decaying plant material, including several species associated only with fenland plants. Ectomycorrhizal fungi, which typically prefer well-drained soils, are few: despite the presence of substantial oaks on fairly open moderately dry ground in the reserve's carr thickets, oak-specific mycorrhizal toadstools are largely and perhaps wholly absent. The probable explanation is that those oaks are recent, and no more likely to be mycologically productive than any new and artificial plantation.[31]

Plants

Notable plants include the fen violet, great fen sedge, marsh pea, greater spearwort, marsh orchids and milk parsley. There are also a number of stonewort species present in the ditches and ponds, along with flowering rush, water milfoil, and yellow and white water lilies.

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Designated Sites View: Wicken Fen". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ "Wicken Fen". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ↑ "Map of Wicken Fen". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ "Cambridgeshire's National Nature Reserves". Natural England. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ Ratcliffe, Derek, ed. (1977). A Nature Conservation Review. Vol. 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 212. ISBN 0521-21403-3.

- ↑ "Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS): Wicken Fen" (PDF). Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ "Fenland SAC". Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ "Fenland SAC (Woodwalton Fen, Wicken Fen & Chippenham Fen)" (PDF). Cambridgeshire County Council. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ "Wicken Fen Nature Reserve". National Trust. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Wicken Fen National Nature Reserve". Wicken Fen..

- ↑ Tim Sands. Wildlife in Trust: a hundred years of nature conservation. The Wildlife Trusts, 2012. Page 672.

- ↑ Rowell, T.A. (1983). History and Management of Wicken Fen. PhD thesis, University of Cambridge.

- 1 2 "Fungi of Wicken Fen, Cambridgeshire: an annotated list". 16 December 2008. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ↑ Labrum, E. A. (1994). Civil engineering heritage. Eastern and central England. London: Institution of Civil Engineers. p. 107. ISBN 9780727719706.

- ↑ "National Mills Weekend: Wicken Fen mill". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ Peter Victor (14 June 1993). "Botanists pave way for return of swallowtail: Britain's largest butterfly is to grace a fen where ideal habitat has been created". The Independent.

- ↑ "Research". Wicken Fen. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2006.

- ↑ Maps of National Trust owned land at Wicken Fen Archived 19 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 18 December 2011

- ↑ "Wicken Fen: The History". National Trust. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ Richard Henry Yapp (1908). "Sketches of Vegetation at Home and Abroad IV. Wicken Fen". New Phytologist. 7 (2/3): 61–81. ISSN 0028-646X. JSTOR 2427007. Wikidata Q101626317.

- ↑ "National Trust Annual Reports". Archived from the original on 26 December 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ↑ "The Wicken Vision - Introduction". National Trust. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/main/w-access-annual-report-09.pdf Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine National Trust Annual Report 2009)

- ↑ Petition supporting the Vision, 846 votes; Petition against the Vision, 418 votes

- ↑ "Vision Bridges the Gap". National Trust. 18 April 2010. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "The Wicken Vision - Lodes Way". National Trust. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ "Cambridge to Wicken Fen walking and cycling network – now a step closer". Sustrans. 4 March 2009. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Wildlife". Wicken Fen. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ↑ "Transactions of the British Mycological Society 19 (4): 280, 1935". www.cybertruffle.org.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ↑ "Wicken Fen (NT) | Pan-species Listing". psl.brc.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- 1 2 "Fungi of Wicken Fen, Cambridgeshire: an annotated list". 16 December 2008. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ↑ "Transactions of the British Mycological Society 36 (4): 304, 1953". www.cybertruffle.org.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

External links

- Wicken Fen National Nature Reserve information at the National Trust

- DEFRA page on enlarging the reserve

- "Wicken Fen citation" (PDF). Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England.

Further reading

- Anthony Day (1985). Turf Village. Cambridgeshire Libraries and Information Service.

- Friday, L.E., ed. (1997). Wicken Fen: the making of a wetland nature reserve. Harley Books, Colchester.

- Friday, L.E., Harley, B. (2000). Checklist of the Flora and Fauna of Wicken Fen. Harley Books, Colchester.