The Hehe (Swahili collective: Wahehe) are a Bantu ethnolinguistic group based in Iringa Region in south-central Tanzania, speaking the Bantu Hehe language. In 2006, the Hehe population was estimated at 805,000,[1] up from the just over 250,000 recorded in the 1957 census when they were the eighth largest tribe in Tanganyika.[2] There were an additional 4,023 of them in Uganda in 2014.[3]

Historically, they are famous for vanquishing a German expedition at Lugalo on 17 August 1891 and maintaining their resistance for seven years thereafter under the leadership of their chief Mkwawa.[4][2]

Etymology

The use of Wahehe as the group's designator can be traced to their war cry,[5] and was originally employed by their adversaries. The Wahehe themselves adopted it only after the Germans and British applied it consistently, but by then the term had acquired connotations of prestige (keeping in mind, of course, the term's roots in Hehe warfare and the victory over the Germans of 1891).

History

It appeared from the Report of the East Africa Commission that, from the point of view of research, the British record in Tanganyika might be exposed to criticism by an international Commission, insomuch as, from reasons of pressing economy following the War, it had been found necessary to suppress the research establishment previously maintained by the Germans.[6]

—Conclusions of a Meeting of the Cabinet, 20 May 1925

"Of scientific literature on British East Africa", remarked John Walter Gregory in 1896, "there is unfortunately little to record. There is nothing which can compare with the magnificent series of works issued in description of German East Africa […] The history of the exploration of Equatorial Africa is one to which Englishmen can look back with feelings of such just pride, that we may ungrudgingly admit the superiority of German scientific work in this region."[7] It is no surprise, therefore, that most of the important sources for the history of the Hehe are German.[8] Once German East Africa was split between the British and Belgian empires after World War I, the interest of German scholars waned,[8] and the British chose not to continue their research.

The people who were eventually to be called Hehe by Europeans, lived in isolation on a highland in southwestern Tanzania, northeast of Lake Nyasa (Lake Malawi), and had few ancestors who had been in Uhehe for more than four generations. With the exception of some pastoralists on the plains and some keeping a limited number of cattle and goats, the Wahehe were primarily an agricultural people. In the beginning they seemed to have lived in relative peace, although the various chiefs did quarrel with one another, raided each other for cattle and broke alliances. The population was probably small, with no chiefdom over 5,000 people. By the middle of the 19th century, however, Nguruhe, one of the more important chiefdoms led by the Muyinga dynasty, began to push its weight around and expand its influence and power.

It was Munyigumbe, of the Muyinga family, who began to create the beginnings of a 'state' by both marriage and conquest. A good deal of this was at the expense of the Wasangu, using the Sangu's own military tactics and even utilizing forms of the Sangu language to properly rouse Hehe warriors to battle. Munyigumba even forced the Wasangu, under Merere II, to move their capital to Usafwa.

With Munyigumba's death in 1878 or 1879, a civil war broke out and a Nyamwezi slave, married to Munyigumba's sister, was able to kill Munyigumba's brother, leaving the unhappy prospect of dealing with Munyigumba's son Mkwawa. Mkwawa killed the Nyamwezi slave, Mwumbambe, at a location called the "place where heads are piled up", and Mkwawa took center stage, a stage that he continued to dominate until the end of the 19th century. John Iliffe describes Mkwawa in his book A Modern History of Tanganyika as "slender, sharply intelligent, brutal, and cruel with a praise-name of the madness of the year".

It was Mkwawa who, by 1880 or 1881,[9] became the sole ruler of Uhehe through war and intimidation. Mkwawa continued expanding Hehe power northwards toward the central caravan routes and afflicting the Wagogo, the Wakaguru, the Germans, etc., and in the south and east, anyone in their way, not least of all their old enemies the Wasangu, who then began turning to the Germans for support. By 1890, the Hehe were the strongest most dominant power in the southeast and began conflicting with that other raiding power, the Germans.

'The Hehe' had no elaborate organization but did have the flexibility to make difficulties for their enemies.

Sub Chief Motomkali Mukini ″Mkini″ was assigned to rule and during his reign had established a military base used to recruit and train at the place so called Ihumitangu, meaning the place where colonial fighters were trained. He was succeeded by his son Galakwila Motomkali Mkini.

Society

The Wahehe reside primarily in Uhehe, an area that:

lies between the Great Ruaha and Kilombero rivers, in the Usungwa mountains and the plateaux which lie in the northern part of the area known as the Southern Highlands. It includes areas of rainforest, high rolling grasslands, a central plateau of Brachystegia woodland and, below the escarpment in the north-east, north and west beside the Great Ruaha River and its tributaries, dry plains covered with thorn scrub.[2]

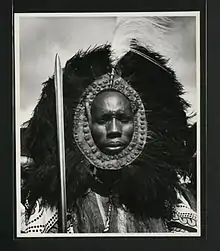

With their armed opposition to German East Africa in mind, colonial descriptions would romanticise the Hehe as "these coarse, reserved mountain people […] a true warrior tribe who live only for war."[2] Their power depended on the spear and on the disciplined force of their armed citizens. Even after firearms became more important the spear remained their chief weapon, for on the open plains the use of spears still had the advantage. The defense of a boma behind palisades or walls with rifles was not their strong point, tactics and a sudden mass spear attack was.

Military organization remained the most important part of Wahehe life and every adult male was a warrior. The youngest lived in the capital, Iringa, where semi-professional warriors trained them. By the 1890s the Hehe had an immediate following of 2,000 to 3,000 men, with another 20,000 men of fighting age who could be mobilized from their scattered homesteads that by 1800 were normally surrounded by large maize fields. It was only later when their military reputation alone was no longer enough and warfare was actually a threat, did they begin to consolidate their villages and begin to build their homes closer together. Only after the wars ended did they once again build further apart with each homestead ideally surrounded by their own fields, larger houses for their many wives were built and could be surrounded by an open courtyard.

While Iliffe considers the Wahehe state to have been unsophisticated, Lt. Nigmann considered the legal system, traditions, and customs to have been quite sophisticated. It is true, however, that all authority came from the chief's will and that conquered chiefdoms were not assimilated but were held by for force, brutality, and fear. Whether one considers the state to be unsophisticated or not, the state was at the same time successful and durable. A visitor it was repeatedly said, could sense an arrogant confidence that was not found elsewhere, and Hehe identity has survived all colonial pressures.

Women captured in war were given to important men, (some men having as many as ten to twenty) who then did almost all of the subsistence agriculture, carried water, and all building material, their housing being well insulated against the violent extremes of heat and cold. A child received his family name, (the praise name) and the types of forbidden food from the father. A Wahehe could not marry anyone with the same praise name and the same forbidden food, even if the relationship could not be traced, and could not marry anyone related through the female line. There was, however, a preference for marrying cross cousins. Most communities contained many households who were related to one another. Two cows and a bull were considered important parts of bride-wealth to be given for a wife.

Although judges (headmen) were subject to bribery (and at times quite willing to accept it), there was a recognized system of courts and law enforcement. Punishment remained fairly simple but had at least some variety. There were penalties of varied types, such as fines or penance, the death sentence, beatings, and the seldom used expulsion from the chiefdom. (excepting the death penalty, crippling or anything attacking the health of the individual, or any type of failing was unknown to the Wahehe.) The village headman was authorized for lighter cases, such as theft or other crimes against property, adultery, personal injury, etc., with the more difficult cases being sent further up the line in the direction of the 'sultan', especially those needing a test administrated by poison. All cases were presented orally and open to all. (Only trials of high treason against the sultan were held in secret.) Two male witnesses were thought sufficient for most 'normal' cases while it was thought that three to five were necessary with female witnesses.

There could be verdicts for betraying or offending the state or its leader, giving false witness, adultery, (one female witness was sufficient, with a fine of one to three head of cattle) incest (very seldom if ever used, since females were quite often married between 10 and 13 years of age and needed three to five witnesses), rape (only the victim was needed as a witness), murder, manslaughter, vendetta, theft, agricultural theft, receiving stolen goods, and swindling were all parts of the judicial concept and had penalties associated with them.

If a divorce took place, the husband was entitled to take all weaned children away from their mother and the mother's family was expected to return the bride-wealth. In spite of this, wives frequently obtained divorces, usually after they had already made arrangements with another man.

The state's strength and power lay in its warriors and their spears, which made it not only disciplined and victorious, but also provided unity and identity, allowing everyone to join in its impressive successes.

Hehe rebellion

The Wahehe were expanding towards the north and east at the same time the Germans were building stations along the central caravan route between the coast and Tabora. Those groups recognizing and accepting German supremacy (showing the German flag) were then brutally attacked, looted, and otherwise destroyed. After futile German attempts to negotiate with them, an expedition was sent out under the leadership of commander Emil von Zelewski.

Since Julius von Soden saw little harm, Zelewski was given the go ahead to attack the Wahehe. As Iliffe relates in A Modern History of Tanganyika and Holger Doebold in Emil Zelewski, with Lt. Tettenborn's official report: The German Schutztruppe, needing to secure the inland area with its main trade and communications, Zelewski, its new commander, broke camp at 6:30, August 17, 1891, riding a donkey at the head of the column. "We burned 25 large village houses and killed 3 tribal warriors. A large group of Wahehe warriors were sighted with only spears and shields but few rifles. Shots from our side were enough to frighten them away". As its center reached the waiting Hehe, an officer shot at a bird. The Hehe grasped their spears and charged. The Askari fired only one or two rounds before they were overwhelmed. "The confusion increased when the pack donkeys of the artillery train panicked and stampeded into the 5th company. Soon the Askari also panicked. Lt. von Heydebreck managed to reach a nearby tembe with black officers Morgan Effendi and Gaber Effendi and twenty Askari." A sixteen-year-old had speared Zelewski on his donkey. In ten minutes most of the column was dead. "I also decided to retreat through the chaos of fleeing porters, pillaging Wahehe, dying warriors, and retreating wounded Askaris.

The rearguard escaped, occupied a hill, raised its flag, and sounded bugle calls to rally survivors. I sent a patrol to guide Lt. Heydebreck, wounded twice by a spear behind his right ear and covered with blood, to our position. NCO Thiemann succumbed to his wounds on the night of 17 to 18 August and we buried him at our tembe position outside the sight of the Wahehe warriors". The Hehe set fire to the grass, burning some of the wounded and hoping to encircle the rearguard. Some 300-400 Hehe followed but did not attack, having already lost 60 dead. Another 200 later died of wounds. The Germans then retreated in the direction of Kondoa. "Still with us are Lt. von Heydebreck, almost recovered from his wounds, Sergeant Kay, NCO Wutzer, Morgan Effendi, Gaber Effendi, 62 Askari (11 of them wounded), 74 porters (seven wounded), four donkeys, and the main part of our baggage.")

Lt. Tettenborn believed that if it had not been for the death of a large number of Wahehe chiefs, Mkwawa incorrectly included, no one would have survived. Saving the main 'part of the baggage' is also incorrect, as it was not saved. Zelewski had started with 13 Europeans, some 320 Askaris, 170 porters, machine guns, and field artillery. Of these, ten Europeans, 256 Askaris, and 96 porters had been lost. The German defeat made a truly enormous impression and the Hehe had now gained reputation as the most powerful soldiers in German East Africa and the Schutztruppe was no longer in a position to continue attacking the Wahehe.

Julius von Soden, the governor now in charge of German East Africa, vetoed revenge: "we should have digested the coast before we devoured the interior". For eighteen months all expeditions were banned, even though the German military was unhappy. In particular, Captain Tom von Prince could not bring himself to leave the Hehe alone and used his forts in the north to invade south into Hehe territory.

Soden left in 1893, his concept ruined. With Colonel Freiherr von Schele, the new governor who brought a policy of aggression, there began the expedition of von Prince, Wynecken, and Zugführer Bauer in support of Merere. Negotiations had failed and caravans continued to be raided until the Germans attacked and took possession of Mkwawa's capital, Iringa, in 1894. This time, however, the Germans were prepared with 609 Askari and three machine-guns. Mkwawa, though, was still not captured, and the Hehe continued to attack their neighbors and kill Germans. There was still no peace. Only with Mkwawa's suicide did 'peace' finally come to Uhehe.

While von Schele, given credit for Mkwawa's final defeat and presented with Germany's highest decoration, was then continually attacked by the political moderates, and finally placed under civilian control from Berlin. Schele then resigned and was followed by more peaceful administrators for the next two years, who nevertheless continued to pressure the Wahehe.

Tom von Prince, after Mkwawa's defeat, indicated great offence with the Wahehe refusal to point out the youth responsible for Zelewski's death. Prince claimed that the German military would never have punished a warrior for following his orders.

By 1896, the Hehe were divided, with some of them beginning to submit to the Germans, and Mkwawa found himself isolated as an outlaw, but always protected by the general Wahehe population. He raided, ambushed patrols, and attacked German outposts, aided by 'loyal Wahehe' and even Sangu warriors of Merere III (son of Merere II). The Germans increased their campaign, searched again and again, even subjecting those who aided Mkwawa to the death penalty. They tried setting up one of Mkwawa's brothers as chief, but had him executed after two months, holding him responsible for the continuing attacks on German patrols.

It was only in July 1898, after being trapped, that Mkwawa shot himself. The Germans removed Mkwawa's head and sent it to Germany. Mkwawa and the Hehe had become so well known that a clause was inserted in the Treaty of Versailles ordering the skull be returned to Uhehe. It was found, not in Berlin, but in Bremen, and was finally returned, not to Iringa, but to nearby Kalenga, and then not until 1956. The identity of the skull is questionable.[10] Mkwawa still today has the status of a national hero in Tanzania, even after over one hundred years.

The Wahehe never again revolted, not during or after Maji Maji, but bureaucrats from Tanzania are still very wary of them. Energy, power, suspicion, intelligence, and a need for a strong hand are still viewed as their characteristics today.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "Ethnologue report for language code: heh". ethnologue.com. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Redmayne 1968, p. 409.

- ↑ "2014 Uganda Population and Housing Census – Main Report" (PDF). Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ Ranger 1968, p. 442.

- ↑ Holmes 1970, p. 205: "[T]he Hehe [are] descendants of a select group who were heard by adversaries to shout 'hee, hee, hee' before engaging in a fight."

- ↑ "Conclusions of a Meeting of the Cabinet held at 10 Downing Street, S.W.1., on Wednesday, May 20th, 1925, at 11.30 a.m." The National Archives. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Gregory 1896, p. ix.

- 1 2 Redmayne 1970, p. 99, where it is noted that, between about 1891 and 1914, "many Germans wrote about German East Africa, its history, geography, geology, botany, zoology, physical anthropology and ethnography."

For details of the German research programme, see Redmayne 1983. - ↑ Redmayne 1970, p. 101.

- ↑ "Der Schädel des Sultans - einestages". Einestages.spiegel.de. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

Bibliography

- Gregory, J. W. (1896). The Great Rift Valley: Being the Narrative of a Journey to Mount Kenya and Lake Baringo. London: John Murray.

- Holmes, C. F. (1970). "Review: Tanzania before 1900 by Andrew Roberts, ed". African Historical Studies. 3 (1): 204–206. doi:10.2307/216503. JSTOR 216503.

- Iliffe, John (1979). A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29611-3.

- Ranger, T. O. (1968). "Connexions between 'Primary Resistance' Movements and Modern Mass Nationalism in East and Central Africa. Part I". The Journal of African History. 9 (3): 437–453. doi:10.1017/s0021853700008665. JSTOR 180275. S2CID 161489985.

- Redmayne, Alison (1968). "Mkwawa and the Hehe Wars". The Journal of African History. 9 (3): 409–436. doi:10.1017/s0021853700008653. JSTOR 180274. S2CID 163016034.

- Redmayne, Alison (1970). "The War Trumpets and Other Mistakes in the History of the Hehe". Anthropos. 65 (1/2): 98–109. JSTOR 40457615.

- Redmayne, Alison (1973). "The Wahehe". In Andrew Roberts (ed.). Tanzania Before 1900 (3rd ed.). Nairobi: East African Publishing House.

- Redmayne, Alison (1983). "Research on Customary Law in German East Africa". Journal of African Law. 27 (1): 22–41. doi:10.1017/S0021855300013267. JSTOR 745621. S2CID 143471803.

Further reading

- Baer, Martin; Schöter, Olaf, Eine Kopfjagt

- Bauer, Andreus, Raising the Flag of War

- Doebold, Holger, Schutztruppe Deutsch Ostafrica & Small Wars

- Nigmann, Ernst (1908). Die Wahehe. Berlin: Ernst Siegfried Mittler und Sohn.

- Patera, Herbert (1939) [1900]. Der Weisse Herr Ohnefurcht. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag.

- Prince, Tom von (1900). Gegen Araber und Wahehe. Berlin: E. G. Mittler & Sohn.

External links

- Hehe at Ethnologue.com