Wah Ming Chang | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 2, 1917 |

| Died | December 22, 2003 (aged 86) Carmel, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Film, sculpture, painting |

| Notable work | Star Trek |

| Spouse | Glenella Taylor |

| Wah Chang | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 鄭華明 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 郑华明 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

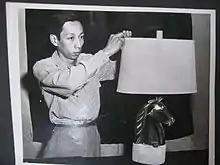

Wah Ming Chang (August 2, 1917 – December 22, 2003) was an American designer, sculptor, and artist. With the encouragement of his adoptive father, James Blanding Sloan, he began exhibiting his prints and watercolors at the age of seven to highly favorable reviews.[1] Chang worked with Sloan on several theatre productions and in the 1940s, they briefly created their own studio to produce films. He is known later in life for his sculpture and the props he designed for Star Trek: The Original Series, including the tricorder and communicator.[2][3]

Early life

The Chang family moved from Honolulu, Hawaii to San Francisco, California and about 1920 opened the Ho-Ho Tea Room on Sutter Street, which became a favorite venue for the city's Bohemian artists. Wah-Ming's mother, Fai Sue Chang, was a graduate of Berkeley's California School of Arts and Crafts (today's California College of the Arts), where she specialized in fashion design and etching. When she died in 1928, her husband persuaded Wah Ming Chang's art teacher and family friends, the highly respected printmaker, puppeteer, and theatre designer, James Blanding Sloan and his wife Mildred Taylor, to become his son's legal guardians. Sloan exhibited Wah Ming's etchings and watercolors in public exhibitions as early as 1925 to favorable reviews in the San Francisco Bay Area and later in the largest art colony on the Pacific Coast, Carmel-by-the-Sea.[4][5][6][7][8][9] The child became part of Sloan's family, traveled in 1926 to Taos, New Mexico, for the on-site study of American Indian culture, and in 1928 displayed his block prints in joint exhibitions with Sloan at the prestigious Philadelphia Print Club[10][11] and in Pasadena, California.[12][13][14]

Career

He became a valued assistant in several of Sloan's marionette theatres as well as in productions for the Hollywood Bowl Ballet and the "Cavalcade of Texas."[1][15] In the mid-1940s Chang formed a joint studio business with Sloan, The East-West Film Company, and produced such memorable films as Pick a Bale of Cotton (an interview and performance with the legendary blues and folk singer Lead Belly in 1944) and the highly controversial anti-war short (1946–47), The Way of Peace, created in part with elaborate miniature sets and puppets in stop-motion.[1]

For Star Trek, Chang built costumes for the salt vampire ("The Man Trap"), the Gorn ("Arena") and Balok's false image ("The Corbomite Maneuver"). He created tribbles by using artificial fur stuffed with foam, the Neanderthals in "The Galileo Seven", and the Romulan Bird of Prey ("Balance of Terror"), and the Vulcan harp first seen in "Charlie X" and later seen in "The Conscience of the King", "Amok Time", "The Way to Eden"; and Star Trek V: The Final Frontier. Chang is mistakenly credited with having designed the phaser; it was actually designed by the Art Director of the original series, Matt Jefferies. The Desilu prop department prepared a single "hero" working model phaser, deemed unacceptable by Gene Roddenberry; Wah Chang prepared additional working and dummy mockups of the phaser, as well as other principal props.[16] A Desilu invoice dated August 22, 1966, shows Chang "reworking phasers" for $520.00.[2]

Chang's communicator design has been credited as an inspiration for modern flip-type cell phones. His Balok effigy was used in "The Corbomite Maneuver" Star Trek episode — and at the conclusion of many closing credits sequences of the series.[16]

His other film credits include sculpting the maquette of Pinocchio which was used as the reference for the animators of the classic Walt Disney feature, and articulated deer models for Bambi.[17] He designed the spectacular headdress worn by Elizabeth Taylor in the feature film Cleopatra. Other work included building the time machine and sphinx from 1960s movie The Time Machine, and the dragon (seen only in the English-dubbed version) of Goliath and the Dragon (1960). Chang's firm, Project Unlimited, Inc., would win Academy Award recognition for its special effects, but Chang was not listed on the award, due to the way the credits were submitted to the academy.[3] Film historian Bob Burns reported that Chang did not object to this. "He was the most humble, gentle man I've ever known in my life," Burns said. "He never boasted about anything he did, and he just did remarkable stuff."[17]

In addition, Chang built the artificial creature in "The Architects of Fear" episode of the original The Outer Limits, some props for the original Planet of the Apes film, the frightening skeleton animated in The Power, the flying machine in The Master of the World, and the dinosaurs in Land of the Lost.

Chang's work as a stop-motion animator through the effects company Centaur Productions, operated with fellow artist Gene Warren, has been enjoyed for years in the cartoons Hardrock, Coco and Joe and Suzy Snowflake.

Later life

Chang moved with his wife, Glenella Taylor, to Carmel Valley, California, in 1970, where he joined the Carmel Art Association and began producing bronze sculptures of wildlife and endangered species.[3][17]

In 1941, Wah Ming was diagnosed with polio following flu-like symptoms. After an extended stay at the Twin Oaks Sanitarium hospital in San Gabriel, California, and treatments that included confinement in an iron lung. He eventually would walk again, but for the rest of his life, never had enough strength in his lungs to be able to blow up a balloon.

While his earlier creative efforts were concerned with special effects and film related wonders, his more mature artistic creations were delightful bronze sculptures and whimsical statuary. The latter ranged from a life-sized 3.5 foot tall Dennis the Menace,[18] commissioned by creator Hank Ketcham and displayed in Dennis Park in Monterey, California, to the smaller statues such as Girl and Frog, which is owned by a private collector in Los Angeles.[19]

Death

Chang died on December 22, 2003, in Carmel Valley at age 86. A public memorial service was held at the Community Church of the Monterey Peninsula in Carmel.[20]

Documentaries

Chang produced the educational 1970 short film Dinosaurs: The Terrible Lizards, a stop-motion feature which discussed life in the Mesozoic Era. It would later gain a "Revised Edition" in 1986.

Chang appeared in the documentary The Fantasy Film Worlds of George Pal (1985) (Produced and directed by Arnold Leibovit).

Mr. Chang was featured in the documentary Time Machine: The Journey Back (1993), produced and directed by Clyde Lucas.

Sculptures

Chang produced bronze sculptures in collaboration with Henry "Bob" Jones after meeting at Disney.[21]

Publications

- Riley, Gail Blasser (1995). Wah Ming Chang: Artist and Master of Special Effects. Berkeley Heights, NJ: Enslow Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89490-639-8.

- Barrow, David; Glen Chang (1989). The Life and Sculpture of Wah Ming Chang. Carmel, CA: Wah Ming Chang. ISBN 978-0-9625293-1-3.

References

- 1 2 3 Edwards, Robert W. (2012). Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold History of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies, Vol. 1. Oakland, Calif.: East Bay Heritage Project. pp. 629–635. ISBN 9781467545679. An online facsimile of the entire text of Vol. 1 is posted on the Traditional Fine Arts Organization website ("Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold History of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies, vol. One, East Bay Heritage Project, Oakland, 2012; by Robert W. Edwards". Archived from the original on 2016-04-29. Retrieved 2016-06-07.).

- 1 2 Solow, Herbert F.; Solow, Yvonne Fern (1997). The Star Trek Sketchbook: The Original Series. Pocket Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. pp. 238–239. ISBN 0-671-00219-8.

- 1 2 3 "Creative Staff: Wah Ming Chang". StarTrek.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ↑ The Oakland Tribune: April 26, 1925, p.6-S; November 27, 1927, p.S-5; July 22, 1928, p.5-S; July 29, 1928, p.6-S.

- ↑ The Argonaut (San Francisco): November 6, 1926, p.15; August 11, 1928, p.169.

- ↑ Carmel Pine Cone: December 9, 1927, p.4; June 28, 1929, p.14; July 5, 1929, p.13.

- ↑ San Francisco Chronicle, July 29, 1928, p.D-7.

- ↑ Carmelite (Carmel, CA), June 26, 1929, p.3.

- ↑ Barrow, David and Glen Chang (1989). Life and Sculpture of Wah Ming Chang. Carmel, CA.: Wah Ming Chang. pp. 1–87. OCLC 23468160.

- ↑ Grafly, Dorothy (1930). "The Philadelphia Print Club". The American Magazine of Art. 21 (4): 203–207. ISSN 2151-254X. JSTOR 23931334.

- ↑ Grafly, Dorothy. "A history of the Philadelphia Print Club". National Gallery of Art Library. Retrieved 2022-10-02.

- ↑ San Francisco Chronicle: August 8, 1926, p.8-F; April 22, 1928, p.D-7.

- ↑ The Christian Science Monitor, August 30, 1926, p. 6.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times, November 25, 1928, p.III-18.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times, July 31, 1932, p.III-16.

- 1 2 Solow, Herbert; Justman, Robert (1996). Inside Star Trek: The Real Story. Pocket Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. pp. 118–119. ISBN 0-671-89628-8. p. 119:

I struck a deal and gave them Matt's detailed working drawings, and they departed, with Wah already planning how he would execute Matt's phaser pistol design, in addition to building the other two props. He finished everything perfectly and made several beautiful hero models of all three props, and all the dummy mockups that I knew the show would require.

- 1 2 3 "Wah Ming Chang, 86; Special-Effects Master Worked on 'Time Machine'". Los Angeles Times. 30 December 2003. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ Coury, Nic (24 June 2016). "Dennis the Menace statue finds permanent home in Monterey". Monterey County Weekly. Retrieved 2022-05-16.

- ↑ Neal Hotelling (13 Jan 2023). "His work animated famous tales" (PDF). Carmel Pine Cone. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. p. 19. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ↑ "Wah Ming Chang, 86; Special-Effects Master Worked on 'Time Machine'". The Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. December 30, 2003. p. 57. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ↑ "Models, Miniatures, and Movie Magic". The Walt Disney Family Museum. 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2016-12-23.

External links

- "The Creator's Story". HeroComm.com. Archived from the original on 2021-10-06. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- Wah Chang at IMDb