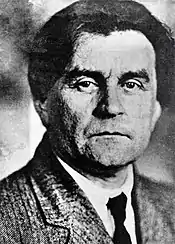

UNOVIS (also known as MOLPOSNOVIS and POSNOVIS) was a short-lived but influential group of artists, founded and led by Kazimir Malevich at the Vitebsk Art School in 1919.

Initially formed by students and known as MOLPOSNOVIS, the group formed to explore and develop new theories and concepts in art. Under the leadership of Malevich they renamed to UNOVIS, chiefly focusing on his ideas on Suprematism and producing a number of projects and publications whose influence on the avant-garde in Russia and abroad was immediate and far-reaching.[1] The group disbanded in 1922.

The name UNOVIS is an abbreviation in Russian of "Utverditeli Novogo Iskusstva" (in Russian: Утвердители НОВого ИСкусства) or "The Champions of the New Art", while POSNOVIS was an abbreviation of "Posledovateli Novogo Iskusstva" (in Russian: ПОСледователи НОВого ИСкусства) or "Followers of the New Art", and MOLPOSNOVIS meant "Young Followers of the New Art" (in Russian: МОЛодые ПОСледователи НОВого ИСкусства).

Foundation and growth

In its short history, the group underwent many changes. First founded as MOLPOSNOVIS, the group's membership started to include some of the school's professors and quickly evolved into POSNOVIS. The group was very active, working on numerous projects and experiments, in most if not all media available at the time. In January 1920, Malevich was invited to teach at the Vitebsk Art School in 1919 by Marc Chagall and immediately appointed by the director of the school at the time, Vera Ermolaeva, to head a teaching studio. In February of the same year, under the leadership of Malevich, the group worked on a "Suprematist ballet", choreographed by Nina Kogan, and the precursor to Aleksei Kruchenykh's influential futurist opera, Victory Over the Sun. Following the production, POSNOVIS underwent more changes and was renamed UNOVIS on February 14, 1920.

Expansion and influence

In early 1920, Marc Chagall selected Malevich to succeed him as director. Malevich accepted and radically reorganized not only UNOVIS but the entire school's curriculum. He transformed UNOVIS into a highly structured organization, forming the UNOVIS Council. Meanwhile, the group's theories and styles were rapidly evolving at the hands of Malevich and his star students and colleagues, including notable Russian artists El Lissitzky, Lazar Khidekel, Nikolai Suetin, Ilia Chashnik, Vera Ermolaeva, Anna Kagan, and Lev Yudin, amongst others. The group's objective was now to introduce Suprematist designs and ideals to Russian society, working with and for the Soviet government:

...organization of design work for new types of useful structures and requirements, and implementation; the formulation of tasks of new architecture; elaboration of new ornamentation (textiles, printed textiles, castings and other products); designs of monumental decorations for use in the embellishment of towns on national holidays; designs for internal and external decoration and painting of accommodation, and implementation; creation of furniture and all objects of practical use; creation of a contemporary type of book and other achievements in the field of printing."[1]

The group took this plan to the streets, furnishing much of Vitebsk in Suprematist art and propaganda. Still, Malevich had more ambitious plans and he urged his students to do bigger, more permanent works — namely architecture.[2] El Lissitzky, who was director of the architectural faculty, worked with Lazar Khidekel and Ilia Chashnik, a young students of his, drafting unorthodox plans for free-floating buildings and enormous steel and glass structures along with more practical designs for housing complexes and even a speaker's podium for the town square. Ilia would go on to succeed Lissitzky as head of the architectural facility along with his fellow student, Lazar Khidekel.

Embracing the Communist ideal, the group chose to share credit and responsibility for all works produced. They signed all works with a solitary black square, a homage to a previous artwork by Malevich. This would become the de facto seal of UNOVIS and took the place of individual names or initials.

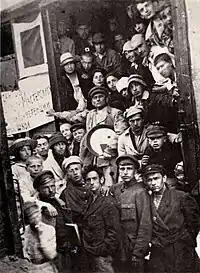

In June 1920 UNOVIS's ambitions accelerated, culminating in a print collection of UNOVIS philosophies and theories such as Lazar Khidekel and Ilya Chashnik, AERO: Articles and Designs (Vitebsk, UNOVIS. 1920), and participation in the "First All-Russian Conference of Teachers and Students of Arts," which took place in Moscow. UNOVIS students who made the trip from Vitebsk to Moscow rapidly distributed artworks, newsletters, manifestos, flyers, and copies of Malevich's "On New Systems in Art" and copies of the "UNOVIS Almanac." UNOVIS succeeded in achieving recognition and became respected as an established and influential movement.

Dissolution and legacy

While their influence on art lasted for generations, their popularity immediately following the conference was short-lived. By 1922, the core group splintered and two contrasting, adverse factions formed. By this time most of the native artists associated with UNOVIS had moved on to other schools, cities, and movements. Even after the group's dissolution, publications bearing the UNOVIS black square appeared for years.

Notable members

See also

References

- 1 2 Essay: Black Square: In the Circle of Malevich and UNOVIS Group Archived 2005-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ UNOVIS – the Bauhaus of the East by Tszwai So, British Library European Studies Blog, 29 October 2019

Bibliography

- Malevich: Suprematism and Revolution in Russian Art 1910-1930 (New York, Thames & Hudson, 1966, ISBN 0-500-09147-1)

- Shishanov V.A.Vitebsk museum of the modern art history of creation and collection. 1918-1941. - Minsk: Medisont, 2007. - 144 p.

- Shishanov, B. "Vitebsk budetlyane" (to a question about the lighting of theatrical experiences UNOVIS in Vitebsk periodicals) / V. Shishanov / / Malevich. Classical avant-garde. Vitebsk - 12 [anthology / ed. T. Kotovich]. – Minsk: Newact, 2010. – P.57-63.

- Lazar Khidekel and Suprematism. Prestel, 2014. Edit. Regina Khidekel, and Charlotte Douglas, Magdalena Dabrowsky, Tatiana Goriatcheva, Alla Rosenfeld, Constantin Boym, Boris Kirikov, Margarita Shtiglits.

.jpg.webp)