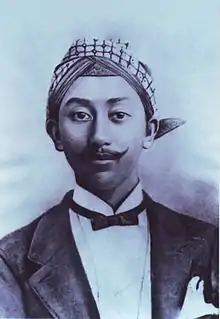

Tirto Adhi Soerjo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Raden Mas Djokomono c. 1880 |

| Died | 7 December 1918 (aged 37–38) Batavia, Dutch East Indies |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Years active | 1894–1912 |

| Spouses |

|

Tirto Adhi Soerjo (EYD: Tirto Adhi Suryo, born Djokomono; c. 1880 – 7 December 1918) was an Indonesian journalist known for his sharp criticism of the Dutch colonial government. Born to a noble Javanese family in Blora, Central Java, Tirto first studied to become a doctor but later focused on journalism. A freelancer since 1894, in 1902 he was made an editor of the Batavia (now Jakarta) based Pembrita Betawi. Tirto established his first newspaper in 1903 and, four years later, created Medan Prijaji as a medium for educated native Indonesians. This proved his longest-lived publication, lasting over five years before Tirto was exiled in 1912 to Bacan for his staunch anti-colonial criticism.

Medan Prijaji is recognised as the first truly "Indonesian" newspaper, and Tirto has been called the father of Indonesian journalism. He was made a National Hero of Indonesia in 2006. The main character in Pramoedya Ananta Toer's Buru Quartet is based on him.

Early life

Tirto was born to a priyayi (noble Javanese) family in Blora, Central Java, sometime between 1872 and 1880.[1] He was raised by his grandparents, who had a stressed relationship with the ruling Dutch colonists after Tirto's grandfather Tirtonoto had been deposed as regent by a Dutch-backed man.[2] Despite this, Tirto was able to attend schools for European youth (Europeesche Lagere School) in Bojonegoro, Rembang, and Madiun. He graduated in 1894; that year he began to dabble in journalism, doing some correspondence for the Malay-language daily Hindia Olanda; he did not receive an honorarium, but was given free newspapers when his works were published.[1][3] Tirto continued his studies to the capital at Batavia (now Jakarta), where he chose to study at the School for Training Native Physicians (STOVIA). The choice was unusual for students of noble descent, who usually went to the school for future government employees.[1]

Tirto spent six years at STOVIA, taking three years of preparatory courses and another three of studies. In his fourth year he left the school, either after dropping out or being expelled. Tirto wrote that he had failed an exam necessary to graduate as he had been too busy writing for Hindia Olanda to study, thus necessitating his withdrawal from the school. Meanwhile, Pramoedya Ananta Toer in his biography of Tirto writes that Tirto was caught giving a prescription to his Chinese wife, while he was not yet qualified to do so, leading to Tirto's expulsion.[1]

Early journalism

Upon leaving STOVIA in 1900 Tirto remained involved in journalism. He began working as an editor of the Batavia-based daily Pembrita Betawi in 1902, working concurrently as an assistant editor for Warna Sari and correspondent for the Surakarta-based Bromartani.[3] His column Dreyfusiana (a reference to the then-ongoing Dreyfus affair in France) contained heated criticism of the Dutch colonial government and the misuse of power. These themes remained common even after Tirto left the newspaper in 1903.[1][3]

Tirto established his own newspaper, Soenda Berita, later that year; it was targeted mainly at native readers, but also catered to ethnic Chinese and Indos to attract advertising revenue. Malaysian historian Ahmat Adam calls Soenda Berita the first native-owned newspaper in the Indies.[3] The publication was not, however, long lasting; following a breach of trust case in which he was accused of stealing an accessory, Tirto was exiled to Bacan in 1904. He soon befriended the sultan, Muhammad Sidik Syah, and on 8 February 1906 Tirto married the sultan's daughter, Raja Fatimah.[4]

Medan Prijaji, SDI and death

After returning to Java in 1906 Tirto began plans for a new Malay-language newspaper, working with various priyayi and merchants. They first united as the Sarekat Priyayi in 1906, and the following year Tirto launched Medan Prijaji, a weekly based in Bandung. He advertised the new newspaper as "a voice for the kings, native nobles, and thoughts of native traders."[lower-alpha 1][5] Though the organization, Sarekat Prijaji, failed, the newspaper was going strong and gaining fame across the whole Dutch-Indies. The newspaper has been widely recognised as the first truly "Indonesian" newspaper, although the medium had been present in the area since Bataviase Nouvelles was established in 1744, as it was owned and operated by native Indonesians, including native reporters, editors, and printers; the target audience was likewise native.[5] Tirto continued to criticise Dutch policies, becoming increasingly explicit; one case in 1909 led to him being imprisoned for two months.[6] During this period he established two smaller publications, Soeloeh Keadilan and the woman-oriented Poetri Hindia.[7]

In 1910 Tirto moved Medan Prijaji to Batavia and made it a daily. The first edition in this new format was published on 5 October 1910; by this time it had around 2,000 subscribers.[6] He continued to write staunch criticisms of the Dutch colonial government and advertised the newspaper as an "organ for the subjugated people in the Dutch East Indies" and "a place for the native voices" .[lower-alpha 2][5] Before he made the newspaper daily, he was briefly exiled to Lampung for an article he wrote in Medan Prijaji. During this era, Tirto also founded, according to his letters, along with Samanhudi later on, Sarekat Dagang Islam (which later, under Tjokroaminoto, turned into SI or Sarekat Islam). Tirto used his house as an early headquarters for SDI and eventually became the organization's Secretary-advisor. He went on several trips across Java to promote the organization and in Solo he met Samanhudi and talked further about the organization. As time goes, he became more and more vocal about the importance of organization and boycott as a weapon for the weak against the oppressor (in this case the Dutch). Criticism of the government and promotion of a nationalist ideology at the time was dangerous, and numerous writers had spent time in prison for expressing their disdain for colonialism. Tirto and Medan Prijaji were able to last until 1912, when the Dutch closed the paper; the last issue was printed on 3 January 1912, and Tirto was sent back to Bacan. One of the reasons he was sent to exile, was his article regarding Rembang's regent, in which he criticized the regent of being weak and manipulative and ultimately blaming him for his wife Kartini's death. The fact that the governor general at the time, Alexander Willem Frederik Idenburg, was at Rembang, mourning for the regent's death, probably made it worse for Tirto. Tirto was also falsely accused by the Dutch of having a big debt to the national bank at the time. After his newspaper was shut down by the Dutch, his name and reputation was damaged and never recovered until his untimely death. Tirto died in 1918, in the hotel he formerly owned, Hotel Medan Prijaji, which by then was already auctioned by Goenawan, Tirto's old friend.[8] The irony is not a single newspaper, at the time, wrote about his death. Only Marco Kartodikromo, one of his employee at Medan Prijaji, whom later became a writer himself, wrote a little obituary about his mentor's death. Tirto was initially buried at Mangga Dua, but then, in 1973, his grave moved because the land was bought by a developer to build a mall there. Now, he is buried along with his family's and descendant's graveyard in Bogor.

Legacy

Syafik Umar, a senior reporter at the Bandung-based daily Pikiran Rakyat, writes that Medan Prijaji laid the framework for modern journalism in Indonesia. He cites the work's layout and nationalistic creed, which was different from the earlier Dutch- and Indo-owned works.[5] Journalist Sudarjo Tjokosisworo described Tirto as the first Indonesian journalist to use the media to shape public opinion. Educator Ki Hajar Dewantara praised Tirto's sharp insights.[6] Others have considered Tirto's work in the media, together with that of Dewantara and Agus Salim, as forging a national identity, a necessary precursor to independence.[9]

For his writings, Tirto was declared a Press Hero in 1973. He was made a National Hero of Indonesia on 3 November 2006 for "outstanding contributions to the nation".[6][10] In his history of Indonesia, Merle Calvin Ricklefs describes Tirto as the "father of Indonesian journalism".[11]

Minke, the main character of Pramoedya Ananta Toer's Buru Quartet, was based on Tirto. As with Tirto, Minke was born in Blora and wrote extensive polemics against the Dutch. Minke likewise established a newspaper named Medan Priyayi and used it as a vehicle for his political views before ultimately being sent into exile. Apart from the tetralogy, Pramoedya also wrote a non-fictional book about Tirto Adhi Soerjo's rise and fall titled 'The Initiator' or 'Sang Pemula' in Indonesian.[12]

An Indonesian news website, Tirto.id, is named in honor of Tirto.[13]

On 10 November 2021, the government of Bogor named R.M. Tirto Adhi Soerjo as street name in the city.[14]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Latif 2005, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Adam 1995, p. 115.

- 1 2 3 4 Adam 1995, p. 109.

- ↑ Adam 1995, p. 110.

- 1 2 3 4 Umar 2006, Koran Nasional Pertama.

- 1 2 3 4 Suara Rakyat 2012, Pahlawanku.

- ↑ Adam 1995, pp. 111, 113.

- ↑ Toer, Pramoedya Ananta (1985). Sang Pemula. Hasta Mitra.

- ↑ The Jakarta Post 2011, The press and society.

- ↑ The Jakarta Post 2006, Freedom fighters.

- ↑ Ricklefs 1993, p. 210.

- ↑ Wijaya 2013, Annelies-Minke.

- ↑ Tirto.id 2016, TENTANG KAMI.

- ↑ "Pahlawan Nasional Bidang Jurnalistik, R.M Tirto Adhi Soerjo Diabadikan Sebagai Nama Jalan Di Kota Bogor (National Hero in Journalism, R.M Tirto Adhi Soerjo Named as Street Name in Bogor) – Bogor Network" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 30 November 2021.

Works cited

- Adam, Ahmat (1995). The Vernacular Press and the Emergence of Modern Indonesian Consciousness (1855–1913). Studies on Southeast Asia. Vol. 17. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-87727-716-3.

- Wijaya, Pandasurya (11 February 2013). "Annelies-Minke, fantasi Pramoedya tentang Tirto Adhi Soerjo" [Annelies-Minke, Pramoedya's Fantasy about Tirto Adhi Soerjo]. Merdeka (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 14 February 2013.

- "Editorial: The press and society". The Jakarta Post. 9 February 2011. Archived from the original on 14 February 2011.

- "Freedom fighters receive national hero title". The Jakarta Post. 10 November 2006. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- Latif, Yudi (2005). Inteligensia Muslim dan Kuasa: Genealogi Inteligensia Muslim Indonesia Abad ke-20 [Muslim Intellectuals and Power: Genealogy of Indonesian Muslim Intellectuals of the 20th Century] (in Indonesian). Bandung: Mizan. ISBN 9789794334003.

- "Pahlawanku Tirto Adhi Soerjo: Penerbit Koran Pertama di Indonesia" [My Hero, Tirto Adhi Soerjo: Publisher of the First Indonesian Newspaper]. Suara Rakyat (in Indonesian). 5 June 2012. Archived from the original on 18 April 2013.

- Ricklefs, M. C. (1993). A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1300 (2nd ed.). MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-333-57689-2.

- "TENTANG KAMI: Jernih, Mengalir, Mencerahkan bersama Tirto.id" [ABOUT US: Clear, Flowing, Enlightening with Tirto.id]. Tirto.id (in Indonesian). 12 May 2016.

- Umar, Syafik (7 February 2006). "Koran Nasional Pertama Lahir di Bandung" [The First National Newspaper Was Born in Bandung]. Pikiran Rakyat (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 4 November 2006.

Further reading

- Lubis, Nina (2006). R.M. Tirto Adhi Soerjo, 1880-1918: Pelopor Pers Nasional [R.M. Tirto Adhi Soerjo, 1880-1918: National Press Leader] (in Indonesian). Bandung: Padjadjaran University. OCLC 70220165.

- Toer, Pramoedya Ananta (1985). Sang Pemula [The Initiator] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Hasta Mitra. OCLC 219790480.

- Cote, Joost (1998). "Tirto Adhi Soerjo and the Indonesian modernity, 1909-1912". RIMA: Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs. 32 (2): 1–43.