| St Winefride's Well | |

|---|---|

_cropped.jpg.webp) | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholicism |

| Patron | Saint Winefride |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Holywell, Flintshire |

| Country | Wales |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Perpendicular Gothic |

| Completed | c. 1512–1525 |

| Materials | Sandstone |

| Website | |

| www | |

St Winefride's Well (Welsh: Ffynnon Wenffrewi) is a holy well and national shrine located in the Welsh town of Holywell in Flintshire. The patron saint of the well, St Winefride, was a 7th-century Catholic martyr who according to legend was decapitated by a lustful prince and then miraculously restored to life. The well is said to have sprung up at the spot where her head hit the ground. This story is first recorded in the 12th century, and since then St Winefride's Well has been a popular pilgrimage destination, known for its healing waters. The well is unique among Britain's sacred sites in that it retained a continuous pilgrimage tradition throughout the English Reformation.

During the Middle Ages, the well formed part of the estate of nearby Basingwerk Abbey. It was visited by several English monarchs, including Richard II and Henry IV. Following the establishment of the Church of England, attempts were made by the Protestant authorities to prevent Catholic pilgrimage to the well, but these attempts were unsuccessful. From the 18th century onwards, the well increasingly attracted secular tourism, and it was commonly believed that the well-water had natural healing properties by virtue of its mineral content. Two bath-houses were built on the site in 1869. In 1917, the well dried up as a result of mining operations in the Greenfield valley; to get it flowing again, water had to be diverted from a new underground source.

The chapel above the well was built in the 16th century. It is a grade I listed building and a scheduled ancient monument. It comprises two parts, the upper chapel and the well crypt. The upper chapel has seen a variety of uses, including service as a sessions house and a secular day school, but is presently used for religious worship. The well crypt contains a star-shaped basin that encloses the well-spring, and an 18th-century statue of St Winefride. Both sections of the chapel are under state guardianship and managed by Cadw.

The well complex is currently open to visitors, who may bathe in the water at certain times of day or fill water bottles from an outdoor tap. There is a visitors' centre and museum on the site. Organised group pilgrimages take place several times a year, and during the pilgrimage season, St Winefride's relic is venerated daily in the well crypt.

Legend of St Winefride

.jpg.webp)

The story of St Winefride, the 7th-century martyr for whom the well is named, is told in two 12th-century Lives: one written by Robert Pennant, prior of Shrewsbury Abbey, and a shorter work of unknown authorship, known as the Vita Prima.[1][note 1] Both works tell substantially the same story of the origin of the well.

Winefride is said to have been the daughter of Teuyth, a chieftain of Tegeingl, who had permitted St Beuno to establish a church within his territory. Beuno became Winefride's religious instructor (later iterations of the story make him Winefride's uncle), and at an early age she took a vow of chastity, intending to devote her life to God. One Sunday morning, while her parents were at Mass, a prince named Caradoc visited their home. Finding Winefride alone, he tried to convince her to sleep with him, threatening to take her by force if she refused. Winefride pretended to consent, only asking that she first be allowed to retire to her room to get changed. By this ruse she managed to escape the house and fled down the valley towards Beuno's church. As she reached it, Caradoc caught up with her and decapitated her with his sword. Her body fell outside the church door, but her head landed inside the threshold, and where it landed, a spring burst forth from the earth.

Beuno came forward and pronounced a curse on Caradoc, who was instantly struck dead. Then Beuno placed Winefride's head back onto her body and prayed for her revival. The prayer was granted and Winefride returned to life, the only trace of her injury being a thin white line around her neck. The two 12th-century sources give differing accounts of her later life, but both agree that she took command of an abbey in Gwytherin, where she eventually died and was buried.

History of the well

Early history

It is not known how long the well has been associated with St Winefride. A fragment of a wooden reliquary from Gwytherin (known as the Arch Gwenfrewi) provides evidence that Winefride was venerated as a saint in the mid-8th century,[2] but the earliest reference to a church in Holywell (which also marks the first time that the town is referred to by that name) is in a document dated 1093, in which the wife of the 1st Earl of Chester grants "the churche of Haliwel" to the monks of St Werburgh's Abbey.[3][4][note 2] It appears that the cult of St Winefride had at this time not achieved any great notoriety, since the medieval historian Giraldus Cambrensis, who visited the area in 1188, does not mention Winefride or the well, and she is also not included in the 12th-century Calendar of Welsh Saints in Cotton Vespasian A.xiv.[6][5]

The grant of the church to St Werburgh's was confirmed by Richard d'Avranches, 2nd Earl of Chester, in 1119, but in 1135, the town and church of Holywell were given into the possession of the newly-established Basingwerk Abbey in Flintshire. The church was briefly transferred back to St Werbergh's between 1157 and 1196, but then reverted to Basingwerk.[3]

During the late Middle Ages the fame of St Winefride began to spread, as the growth of Marian culture in Europe caused a surge of interest in female saints.[7] One focal point of Winefride's cult was Shrewsbury Abbey, which had taken possession of the saint's remains in 1137,[8] but Holywell also received large numbers of pilgrims, who came to offer their devotions and to take advantage of the reputed healing power of the water.[9]

Among the pilgrims were several English monarchs. The first known royal visit to the well was that of Richard II in 1398.[10][note 3] Richard appointed a chaplain to say regular masses at the well; the office came with an annual pension which was kept up by successive monarchs until the 16th century.[13][note 4] Henry IV took a pilgrimage to the well in 1403, following his victory at the Battle of Shrewsbury, possibly in order to give thanks to Winefride for saving the life of his son, who had sustained an arrow wound during the battle. On the other hand, Henry's visit may have been politically motivated; by moving north he was positioning himself to head off a potential Welsh invasion, and his devotions at the well sent a message to the people of Cheshire (an area hostile to his rule) that the saint endorsed his victory.[14] Henry seems to have established the first chapel over the well, which is described as having had three strong walls and a "great gate" on the fourth side.[15]

Henry V may have made a pilgrimage from Shrewsbury to Holywell sometime around 1416, though the documentary evidence is ambiguous.[16] The medieval Welsh poet Tudur Aled said of St Winefride's Well that "every earl used to go, every courtier, every king", and mentions a pilgrimage to the site by Edward IV. Though the poem gives no indication of the date of this pilgrimage, Edward was active in the area in 1461, around the time of his crowning; like Henry before him, he may have wished to secure a political advantage by showing that Winefride supported his cause.[17]

The chapel built by Henry IV apparently did not survive for long, possibly because it was not sturdy enough to withstand the force of the water.[18] The chapel that stands on the site today is traditionally said to have been built by Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII, shortly after the 1485 Battle of Bosworth,[19] but there is no contemporary evidence to support this claim. A 16th-century poem by Siôn ap Hywel says that the funding for the chapel was provided by Abbot Thomas Pennant of Basingwerk in 1512, and modern historians consider this a more plausible account.[20][21] Tree-ring dating of one of the building's principal rafters has shown that the roof timbers were likely put in place around 1525.[21]

English Reformation

In 1534, Henry VIII officially rejected the authority of the Pope and established the Church of England, an act that dramatically altered the nation's religious landscape. Catholicism was outlawed, and traditional practices such as pilgrimage and the veneration of saints were condemned as heretical.[22][23] Despite this, St Winefride's Well continued to attract large numbers of Catholic pilgrims throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. The well's uninterrupted pilgrimage tradition makes it unique among the sacred sites of Britain.[24]

Basingwerk Abbey was dissolved circa 1537. The abbey's possessions reverted to the Crown, and St Winefride's Well was leased out to a member of the royal household, who in turn leased it to one William Holcroft. The terms of the lease entitled Holcroft to receive all donations offered by pilgrims at the shrine, but he soon came into conflict with a group of local Catholics, who brought their own donation boxes to the well and urged the pilgrims not to give their money to a servant of the king.[25] The zeal of the locals helped protect the well chapel from the organized iconoclasm of the following decades, and the income generated by the site gave the authorities good reason not to suppress its operation.[26]

However, anti-Catholic laws were more rigorously enforced during the reign of Elizabeth I, after the papal bull Regnans in Excelsis commanded English Catholics to rebel against their monarch. Any large gathering of Catholics was henceforth considered a threat to national security; notwithstanding this, the well's popularity as a pilgrimage site was undiminished.[27] In 1579, Elizabeth ordered that the water be tested to determine if it had any natural curative properties. If so, access was to be restricted only to "diseased persons"; if not, then the chapel was to be torn down. It is unknown what resulted from this order, but the chapel remained standing and pilgrimage continued.[28] In 1590, the Society of Jesus dispatched John Bennett to minister to Catholics in Holywell, and the Jesuits maintained a presence in the town up until the 20th century.[29]

17th century

In 1605, under the reign of James I, the Jesuit Henry Garnet led a pilgrimage from Enfield to St Winefride's Well, stopping along the way at the homes of several people who were later implicated in the Gunpowder Plot. Garnet was accused of using the pilgrimage as cover for a "conference of the conspirators", though modern historians consider this unlikely.[31][32] The backlash against the failed plot resulted in even greater legal intolerance of Catholics and sharper punishments for recusancy (refusal to attend Anglican services). Catholics were required to take an Oath of Allegiance which denied the authority of the Pope over the king.[33]

In 1617, Bishop Richard Parry made an effort to prevent the "superstitious flocking" of Catholics to St Winefride's Well by requiring "that the oath of supremacie and allegiance be ordered unto all such strangers (before they go to the Well) as shall refuse to come to church, by which reason whereof the great concourse is stopped".[34] If Parry did succeed in keeping pilgrims from the well, his victory was short-lived. Just three years later, a Catholic source reported that the Bishop of Bangor, Lewis Bayly, "went in person to arrest the priests and Catholics" who were visiting the well around the time of Winefride's feast day, whereupon "the people from about the countryside rose up, even though most of them are heretics [Protestants] and seized the bishop and handled him roughly and then threw him into a ditch".[35]

In 1626, Chief Justice of Chester John Bridgeman undertook to solve the problem of St Winefride's. He ordered local innkeepers to pass the names of their guests on to the authorities, and summoned all recusants to take the Oath of Allegiance in court. Before the year was out, he confidently reported that pilgrimage to the well had ceased. Once again, however, this success was only temporary. On 3 November 1629, a crowd of 1,400 "knights, ladies, gentlemen and gentlewomen of divers countries", along with an estimated 150 Catholic priests, gathered at the well to celebrate St Winefride's feast day.[36][37] The Bishop of St Asaph, in his annual reports to the Archbishop of Canterbury, repeatedly complained about the number of people visiting the well, until in 1637 John Bridgeman returned to the fray. This time, he instituted more extreme measures to stem the tide of pilgrimage. All but two of the inns at Holywell were closed, the statue of Winefride in the shrine was disfigured, the iron posts around the spring for the support of the bathers were removed, and orders were given to report the names and addresses of every pilgrim. Bridgeman also suggested building a wall to block access to the well-basin; it is unknown whether he actually attempted this, but the columns of the basin exhibit signs of damage that may be consistent with such an attempt. Further damage to the chapel occurred during the English Civil War, possibly by the Parliamentary soldiers who passed through Holywell in November 1643.[38]

Not all Protestants denied the efficacy of healing wells, though they did not believe the cures to be effected by any supernatural agency. Medicinal spas had become popular during the Elizabethan era, and 17th-century physicians sought to prove that certain springs could provide powerful health benefits on account of the mineral content of the water.[39] There are many recorded visits to St Winefride's Well by Protestants, with at least one having received permission from his parish priest to make the journey. Contemporary Catholic sources report several miraculous cures and conversions of Protestants at the well.[40][41]

The accession to the throne in 1685 of the Catholic James II brought a brief period of respite to the persecuted pilgrims. James's wife, Mary of Modena, settled a debate between the Jesuits and the secular clergy at Holywell by giving the well chapel into the sole possession of the Jesuits. James visited the well in August 1687 to pray for a son, and donated £30 for the repair of the upper chapel, which until that time was being used as a sessions house. The following year, however, James was deposed by William and Mary, and England once again became a Protestant country.[42]

18th century to present

During the 18th century, St Winefride's Well was increasingly frequented not only by pilgrims but also by tourists and curiosity seekers. Travel was becoming easier, and newspapers and pamphlets were spreading the word about the well and its healing waters. The well became an essential stop on the tourist itinerary; among those who visited were Celia Fiennes, Daniel Defoe and Samuel Johnson.[43] The secularization of holy wells continued, with cures being attributed to the chemical composition of the water rather than to the intervention of the patron saint.[44] In 1722, the upper chapel was converted into a day school.[45] In 1795, the antiquary Thomas Pennant noted that the number of Catholic pilgrims visiting the well had "considerably decreased".[46]

This was to change in 1805, when a dramatic and heavily-publicized cure sparked a revival of interest. A young woman named Winefrid White, who for years had been paralyzed down the left side and unable to walk without a crutch, bathed in St Winefride's Well and made an immediate recovery. Bishop John Milner published an account of the incident, in which he collated the testimonies of multiple witnesses and described the event as an "evident miracle" which defied scientific explanation. This public affirmation of the miraculous power of the well, helped along by the growing Romantic fascination with medieval history, reignited Holywell's pilgrimage tradition.[47][48] The upper chapel was once again used for religious services from 1841.[49]

In 1859, it was discovered that the foundations of the chapel had eroded away, and the building was in a dangerous condition. The water was diverted for several days while workmen underpinned the well pool with ashlar stone and flagged the plunge bath.[50] In 1869, work began on the construction of two new buildings in the vicinity of the well. The first, called the Well House, was a three-storey bath-house which doubled as the caretaker's residence; the second was a swimming pool called the Westminster Bath. These buildings were completed by April 1871. A turnstile was installed at the entrance to the well complex, and a fee was charged for admittance.[51] In 1886, a statue of St Winefride was placed in the niche at the entrance to the well, which had stood empty since the 1630s.[52]

On 5 January 1917, St Winefride's Well ran dry. The water supply had been tapped by a drainage tunnel that was under construction near Bagillt. It had already been observed in 1885 that the drainage schemes connected with the lead mining operations in the Greenfield valley were affecting the output of the well, but the concerns of Holywell residents had been overridden. After the well dried up completely, the search began for an alternative source. A disused mine shaft northwest of Holywell was converted into a pumping plant, which was used to raise an underground water supply and divert it along a drainage tunnel known as the Holway Level. Water was then piped from this tunnel into the well basin. The well began to flow again on 22 September, and there was no indication that the water had lost any of its curative powers.[53]

In 1930, the first section of the stream that issues from the plunge bath was covered over, and the former brewery that stood beside the stream was demolished. The site was landscaped into a garden called St Winefride's Park.[54] In the 1990s, the Well House was transformed into a museum and library, and the Westminster Bath into a visitors' centre. In 2010, the guardianship of the well crypt was transferred to Cadw (who had already been responsible for the maintenance of the upper chapel since the mid-twentieth century). Restoration work was carried out in the crypt which involved strengthening the masonry, replacing missing flooring slabs, and repairing damage caused by humidity, candle-smoke and fires. New gates and railings were also erected.[55]

The site was designated a national shrine in November 2023.[56]

Miracles

Numerous miracles have been attributed to the well, from the 12th century down to the present day. The two earliest Lives contain lengthy accounts of miraculous cures which came about through Winefride's intercession, and of punishments visited upon those who violated the sanctity of the site.[57][58] A list of supposed miracles occurring in the 17th century was compiled by the Jesuit priest Philip Metcalf, and an account of 18th- and 19th-century miracles was provided by Charles De Smedt.[59] A further update, including 20th-century cures, was written by Herbert Thurston in 1922.[60] Until the 1960s, crutches and surgical boots left behind by pilgrims were arranged around the well or hung up on the walls;[61][54] some of these crutches are now on display in the visitors' centre.

Devotional practices

St Winefride's Well remains a popular pilgrimage destination, and its long association with healing has earned Holywell the title of "the Lourdes of Wales". The traditional method of bathing in the well is to pass three times through the small pool adjacent to the spring while reciting one decade of the Rosary, and then to move into the outer pool and kneel on a submerged stone, known as St Beuno's stone, for as long as it takes to complete the prayer.[24][61] 18th-century visitors also reported a tradition of ducking one's head under the water to kiss St Beuno's stone and make a wish.[62][63] The ritual of the triple immersion has its origin in Robert of Shrewsbury's Life of Winefride, in which Beuno prophesies to Winefride as follows:[64][65]

Whoever shall at any time, in whatsoever sorrow or suffering, implore your aid for deliverance from sickness or misfortune, shall at the first, or the second, or certainly the third petition, obtain his wish, and rejoice in the attainment of what he asked for.

A 1670 drawing of the chapel shows a small structure to one side of the main spring, labelled "The Little Spring for the cure of sore eyes".[62] Thomas Pennant, writing in 1796, described the ritual connected with this spring: "The patient made an offering to the nymph of the spring, of a crooked pin, and sent up at the same time a certain ejaculation, by way of charm: but the charm is forgotten, and the efficacy of the waters lost."[66] The site of the Little Spring is now buried beneath the Well House.

Today, the well is open to the public, but bathing is permitted only at certain times. Filtered well-water is available from a tap; historically, the water has been thought to retain its potency even when removed from the site.[67] The museum within the complex exhibits a piece of the True Cross along with the relics of various saints, including the surviving fragment of the Arch Gwenfrewi and a piece of bone believed to be Winefride's.[65]

Organised group pilgrimages take place several times a year. The most popular of these is the June pilgrimage, which involves a procession from the nearby St Winefride's Church to the well, a Mass in the well garden given by the Bishop of Wrexham, and the veneration of Winefride's relic.[68][61] During the pilgrimage season (from Pentecost to the last Sunday in September), there is a daily service in the well crypt.[24]

Natural features

.jpg.webp)

The spring feeding St Winefride's Well was once much stronger than it is today.[69] In the late Medieval period, it was said that anything dropped into the well would be carried away downstream before it had time to sink.[70] The poet John Taylor wrote in 1652 that the well "doth continually work and bubble with extreme violence, like a boiling cauldron or furnace".[71] In 1731, a group of Anglican visitors measured the time it took for the well basin to fill, and concluded that the spring "raises more than one hundred tons of water in a minute".[72] This estimate matches that recorded by Samuel Johnson in his diary when he passed through the area in 1774:[73]

The spring called Winifred's Well is very clear, and so copious that it yields one hundred tuns of water in a minute. It is all at once a very great stream which within perhaps thirty yards of its eruption turns a mill and in a course of two miles eighteen more.

In 1859, the draining of the well basin for repair work gave another opportunity of measuring the power of the spring. On this occasion, the reported output was 22½ tons per minute.[50] In the modern day, the spring is still said to yield an unusually large quantity of water.[74] A pile of stones has been placed over its point of emergence to prevent it from becoming a fountain.[61]

In former times the bed of the stream was littered with red stones, which according to legend were permanently stained with Winefride's blood.[75] The actual cause of the stones' colour may have been natural iron deposits in the water,[76] or the presence of a red-coloured algae, Trentepohlia jolithus, which can still be seen growing on the north wall today.[77] The well was also known for its moss, which reportedly had a sweet smell and was referred to as "St Winefride's hair".[65][78] The stones and the moss were commonly taken from the site by pilgrims, who treated them as charms or relics.[67][65] One sceptical visitor, Celia Fiennes, claimed in 1698 that the well's custodians replenished the moss daily from a nearby hill.[79]

Architecture of the chapel

The well chapel is a grade I listed building (designated 1951)[80] and a scheduled ancient monument.[81] It comprises two parts: the upper chapel, where church services are held, and the well crypt beneath it, which encloses the spring. The hillside has been cut away so that the crypt can be entered from the north, while the upper chapel is entered from the south.[81][82]

The building is in the Perpendicular style. Its exterior walls are of coursed sandstone, which was imported from the Wirral towns of Storeton and Bebington. It has a low-pitched roof with a crenellated parapet. The upper chapel comprises a four-bay nave, a three-bay north aisle, and a semi-octagonal chancel, with window tracery featuring a mix of basket arches and ogee arches. There is a narrow stone bench around the chancel interior, and sockets in the stonework which suggest that a rood screen was once installed in the chancel arch. The roof is arch-braced and decorated with foliage bosses. The corbels supporting the braces and the arches of the north arcade are carved into a variety of figures, including animals, grotesques, and family emblems.[80][83]

An external staircase at the west end of the chapel (now blocked) leads down into a gallery that overlooks the well crypt, and then down into the crypt itself through a spandrelled doorway that was once the principal entrance. There are two more doorways in the north wall of the crypt, surmounted by large unglazed windows. Another unglazed window, stretching nearly the entire height of the crypt, sits between them, looking out onto the plunge pool. A band of carved animals runs along the outer wall. The crypt's interior is centred around the star-shaped well basin, which supports a ring of stone columns. The columns were once linked by traceried screens, with basket-arched openings providing a view of the spring. Above the spring is a tierceron vault, with a pendant boss that displays six scenes from the life of St Winefride. The vaulted ceiling of the crypt contains many other carved bosses representing various subjects. In the northeast corner is a niche with a crocketed canopy, which holds a statue of St Winefride.[80][81][84]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Watercolour painting by John Warwick Smith, c. 1790

Watercolour painting by John Warwick Smith, c. 1790 Sketch by Robert Chambers, 1832

Sketch by Robert Chambers, 1832 Hand-pump by the bathing pool

Hand-pump by the bathing pool Sculpture of St Winefride near the chapel

Sculpture of St Winefride near the chapel Visitors' centre, formerly the Westminster Bath

Visitors' centre, formerly the Westminster Bath Apse of the upper chapel

Apse of the upper chapel West door of the well crypt

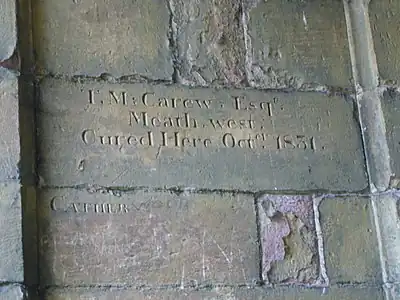

West door of the well crypt Inscription left by a cured pilgrim

Inscription left by a cured pilgrim.jpg.webp) Vaulted ceiling above the well basin

Vaulted ceiling above the well basin Pendant boss above the well basin

Pendant boss above the well basin

See also

Notes

- ↑ For a modern English translation of these Latin texts, see Pepin & Feiss 2011. Older translations, accessible online, can be found in Swift 1888, pp. 30–66 (Robert's Life), and Rees 1853 (Vita Prima).

- ↑ The Domesday Book of 1086 makes no mention of Holywell, but it does record a "Weltune", which may be a translation of the town's Welsh name Treffynnon (Well-town).[5]

- ↑ Richard I is often said to have visited the well in 1189, but this claim is based on a misreading of an 18th-century source. Thomas Pennant, writing in 1778, describes a pilgrimage made in 1119 by Richard d'Avranches, 2nd Earl of Chester. He introduces this account by saying that "Richard ... began his reign with an act of piety".[11] Later authors confused the two Richards, which gave rise to the idea that Richard I made a pilgrimage to the well in the first year of his reign.[12] According to Pennant, Richard d'Avranches was attacked by the Welsh and took shelter in Basingwerk Abbey; this is the same story that later authors tell of Richard I.

- ↑ Existing documents show that Edward IV, Richard III, Henry VII and Henry VIII each confirmed the appointment of a chaplain at the well. The evidence that the office dates back to Richard II comes from letters patent issued by Edward IV in 1465, in which he says that the celebration of mass over the well "was done from the time of our noble progenitor Richard II until a short time since". If there was no chapel at the actual site of the well during Richard II's reign, then the priest may have originally served at a side-chapel in the parish church.[13]

References

- ↑ Scully 2007, p. 203.

- ↑ Hamaker 2011, p. 120–121.

- 1 2 Turner 2019, p. 245.

- ↑ Thomas 1874, p. 466.

- 1 2 Baring-Gould & Fisher 1911, pp. 187–188.

- ↑ Hamaker 2011, p. 121.

- ↑ Hamaker 2011, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Bartlett 2004, p. 80.

- ↑ Hamaker 2011, p. 122.

- ↑ Hurlock 2018, p. 185.

- ↑ Pennant 1883, p. 31.

- ↑ Hurlock 2018, p. 201.

- 1 2 Pritchard 2009, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Hurlock 2018, p. 186.

- ↑ Turner 2019, pp. 247, 250.

- ↑ Hurlock 2018, pp. 186, 202.

- ↑ Hurlock 2018, pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Turner 2019, pp. 250–251.

- ↑ Hurlock 2018, p. 125.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, pp. 80–82.

- 1 2 Turner 2019, pp. 262–264.

- ↑ Seguin 2003, p. 2.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, p. 109.

- 1 2 3 Stumpe 2009, p. 67.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, pp. 94, 97–98.

- ↑ Walsham 2014, pp. 183–184.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Seguin 2003, p. 9.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, p. 135.

- ↑ Jones 1954, p. 77.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, pp. 145–148.

- ↑ Fraser 1996, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, p. 148.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, p. 149.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, p. 151.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Seguin 2003, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, pp. 162–165.

- ↑ Walsham 1999, pp. 246–250.

- ↑ Walsham 1999, p. 255.

- ↑ Seguin 2003, p. 8.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, pp. 188–197.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, pp. 216–217, 219, 223.

- ↑ Jones 1954, p. 68.

- ↑ Jones 1954, p. 70.

- ↑ Pennant 1796, p. 230.

- ↑ Champ 1982, pp. 153, 159–164.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, pp. 243–248.

- ↑ Rees 2012, p. 468.

- 1 2 Pritchard 2009, pp. 267–268.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, pp. 272–276.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, p. 305.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, pp. 380–395.

- 1 2 Pritchard 2009, p. 397.

- ↑ Rees 2012, pp. 467–475.

- ↑ Caldwell, Simon (18 November 2023). "Bishops elevate St Winefride's Well to status of national shrine". Catholic Herald.

- ↑ Swift 1888, pp. 76–83.

- ↑ Rees 1853, pp. 520–529.

- ↑ Both works are reproduced in Swift 1888, pp. 85–108.

- ↑ Hamaker 2011, p. 124.

- 1 2 3 4 Bord 1994, p. 99.

- 1 2 Pritchard 2009, p. 220.

- ↑ Pennant 1796, p. 223.

- ↑ Swift 1888, pp. 32–33.

- 1 2 3 4 Stumpe 2009, p. 69.

- ↑ Pennant 1796, p. 223–224.

- 1 2 Champ 1982, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Stumpe 2009, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Turner 2019, p. 251.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, p. 30.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, p. 174.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ McAdam, Hyde & Hyde 1958, pp. 185–186.

- ↑ Scully 2007, p. 202.

- ↑ Scully 2007, p. 204.

- ↑ Jones 1954, p. 39.

- ↑ Rees 2012, p. 475.

- ↑ Pritchard 2009, p. 33.

- ↑ Morris 1947, pp. 180–181.

- 1 2 3 "St. Winifrides's Chapel & Well". Full Report for Listed Buildings. Cadw.

- 1 2 3 "St Winefride's Chapel and Well". Scheduled Monuments – Full Report. Cadw.

- ↑ Turner 2019, pp. 251–252.

- ↑ Turner 2019, pp. 251–252, 275.

- ↑ Turner 2019, pp. 258–262.

Primary sources

- McAdam, E. L.; Hyde, D.; Hyde, M., eds. (1958). Samuel Johnson: Diaries, Prayers, and Annals. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-00733-7.

- Morris, Christopher, ed. (1947). The Journeys of Celia Fiennes. The Cresset Press.

- Pepin, R.; Feiss, H., eds. (2011). Two Mediaeval Lives of Saint Winefride. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-61097-492-9.

- Rees, W. J., ed. (1853). "Life of St. Winefred". Lives of the Cambro-British Saints. Longman & Co.

- Swift, Thomas, ed. (1888). The Life of Saint Winefride, Virgin and Martyr. Burns and Oates Ltd.

Secondary sources

- Baring-Gould, S.; Fisher, John (1911). "Gwenfrewi, or Winefred, Virgin, Martyr". The Lives of the British Saints. Vol. 3. Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion.

- Bartlett, Robert (2004). "Cults of Irish, Scottish and Welsh saints in twelfth-century England". In Smith, Brendan (ed.). Britain and Ireland 900–1300: Insular Responses to Medieval European Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57319-X.

- Bord, Janet (1994). "St Winefride's Well, Holywell, Clwyd". Folklore. 105 (1–2): 99–100. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1994.9715879.

- Champ, Judith F. (1982). "Bishop Milner, Holywell, and the cure tradition". Studies in Church History. 19: 153–164. doi:10.1017/S0424208400009359.

- Fraser, Antonia (1996). Faith and Treason: The Story of the Gunpowder Plot. Nan A. Talese. ISBN 0-385-47189-0.

- Hamaker, Catherine (2011). "Winefride's Well-Cult". In Pepin, R.; Feiss, H. (eds.). Two Mediaeval Lives of Saint Winefride. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-61097-492-9.

- Hurlock, Kathryn (2018). Medieval Welsh Pilgrimage, c. 1100–1500. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-43098-4.

- Jones, Francis (1954). Holy Wells of Wales. University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-1145-8.

- Pennant, Thomas (1796). The History of the Parishes of Whiteford and Holywell. B. and J. White.

- Pennant, Thomas (1883) [1778]. Tours in Wales. Vol. 1. H. Humphreys.

- Pritchard, T. W. (2009). St Winefride, Her Holy Well and the Jesuit Mission, c.650–1930. Bridge Books. ISBN 978-1-84494-060-8.

- Rees, Sian E. (2012). "The conservation of tranquility: St Winefride's Well and Llanfihangel Ysceifiog old parish church". In Britnell, W. J.; Silvester, R. J. (eds.). Reflections on the Past: Essays in Honour of Francis Lynch. Cambrian Archaeological Association. ISBN 978-0-947846-08-4.

- Scully, Robert E. (2007). "St. Winefride's Well". In Cormack, Margaret (ed.). Saints and Their Cults in the Atlantic World. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-630-9.

- Seguin, Colleen M. (Summer 2003). "Cures and controversy in early modern Wales: the struggle to control St. Winifred's Well" (PDF). North American Journal of Welsh Studies. 3 (2): 1–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2006.

- Stumpe, Lynne H. (December 2009). "Display and veneration of holy relics at St Winefride's Well and Stonyhurst". Journal of Museum Ethnography (22): 63–81. JSTOR 41417138.

- Thomas, D. R. (1874). "Holywell". A History of the Diocese of St. Asaph. James Parker & Co.

- Turner, Rick (2019). "The architecture, patronage and date of St Winefride's Well, Holywell". Archaeologia Cambrensis. 168: 245–275.

- Walsham, Alexandra (1999). "Reforming the waters: holy wells and healing springs in Protestant England". Studies in Church History Subsidia. 12: 227–255. doi:10.1017/S0143045900002520.

- Walsham, Alexandra (2014). "Holywell and the Welsh Catholic Revival". Catholic Reformation in Protestant Britain. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-754-65723-1.

External links

53°16′38″N 3°13′25″W / 53.2771°N 3.2236°W