The Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Fund (collectively, the Social Security Trust Fund or Trust Funds) are trust funds that provide for payment of Social Security (Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance; OASDI) benefits administered by the United States Social Security Administration.[1][2][3]

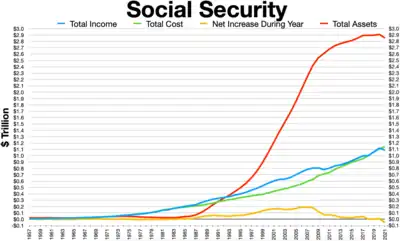

The Social Security Administration collects payroll taxes and uses the money collected to pay Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance benefits by way of trust funds. When the program runs a surplus, the excess funds increase the value of the Trust Fund. As of 2021, the Trust Fund contained (or alternatively, was owed) $2.908 trillion [4] The Trust Fund is required by law to be invested in non-marketable securities issued and guaranteed by the "full faith and credit" of the federal government. These securities earn a market rate of interest.[5]

Excess funds are used by the government for non-Social Security purposes, creating the obligations to the Social Security Administration and thus program recipients. However, Congress could cut these obligations by altering the law. Trust Fund obligations are considered "intra-governmental" debt, a component of the "public" or "national" debt. As of December 2022 (estimated), the intragovernmental debt was $6.18 trillion of the $31.4 trillion national debt.[6] Of this $6.18 trillion, $2.7 trillion is an obligation to the Social Security Administration.

According to the Social Security Trustees, who oversee the program and report on its financial condition, program costs are expected to exceed non-interest income from 2010 onward. However, due to interest (earned at a 3.6% rate in 2014) the program will run an overall surplus that adds to the fund through the end of 2019. Under current law, the securities in the Trust Fund represent a legal obligation the government must honor when program revenues are no longer sufficient to fully fund benefit payments. However, when the Trust Fund is used to cover program deficits in a given year, the Trust Fund balance is reduced. One projection scenario estimates that, by 2034, the Trust Fund could be exhausted. Thereafter, payroll taxes are projected to only cover approximately 76% of program obligations.[7]

There have been various proposals to address this shortfall, including: reducing government expenditures, such as by raising the retirement age; tax increases; and, borrowing.

Structure

The "Social Security Trust Fund" comprises two separate funds that hold federal government debt obligations related to what are traditionally thought of as Social Security benefits. The larger of these funds is the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund, which holds in trust special interest-bearing federal government securities bought with surplus OASI payroll tax revenues.[8] The second, smaller fund is the Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund, which holds in trust more of the special interest-bearing federal government securities, bought with surplus DI payroll tax revenues.[9]

The trust funds are "off-budget" and treated separately in certain ways from other federal spending, and other trust funds of the federal government. From the U.S. Code:

EXCLUSION OF SOCIAL SECURITY FROM ALL BUDGETS

Pub. L. 101–508, title XIII, Sec. 13301(a), Nov. 5, 1990, 104 Stat. 1388-623, provided that: Notwithstanding any other provision of law, the receipts and disbursements of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund and the Federal Disability Insurance Trust Fund shall not be counted as new budget authority, outlays, receipts, or deficit or surplus for purposes of - (1) the budget of the United States Government as submitted by the President, (2) the congressional budget, or

(3) the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985.

The trust funds run surpluses in that the amount paid in by current workers is more than the amount paid out to current beneficiaries. These surpluses are invested in special U.S. government securities, which are deposited into the trust funds. If the trust funds begin running deficits, meaning more in benefits are paid out than contributions paid in, the Social Security Administration is empowered to redeem the securities and use those funds to cover the deficit.

Governance

The Board of Trustees of the Trust Funds is composed of six members:[1][2]

- Secretary of the Treasury (the Managing Trustee),

- Secretary of Labor,

- Secretary of Health and Human Services,

- Commissioner of Social Security, and

- Two members appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate for a term of four years.

| Name | Position | Appointed by | Sworn in | Term expires |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Janet Yellen | Treasury | ex officio | — | — |

| Julie Su (acting) | Labor | ex officio | — | — |

| Xavier Becerra | Health and Human Services | ex officio | — | — |

| Kilolo Kijakazi (acting) | Social Security Administration | ex officio | — | — |

| Vacant | Public Trustee | — | — | — |

| Vacant | Public Trustee | — | — | — |

The Board of Trustees holds the trust funds.[10] The Managing Trustee is responsible for investing the funds,[11] which has been delegated to the Bureau of the Fiscal Service.[12]

History

The Social Security system is primarily a pay-as-you-go system, meaning that payments to current retirees come from current payments into the system. The program was initially established in 1935 in response to the Great Depression. The first to file for Social Security was Ida Mae Fuller in 1940.[13] Fuller paid $24.75 in taxes during her three years working under the social security program, and drew an aggregate of $22,889 in benefits before passing at age 100. This represents a ratio of $925 in benefits for every dollar she paid into the program.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter and the 95th Congress increased the FICA tax to fund Social Security, phased in gradually into the 1980s.[14] In the early 1980s, financial projections of the Social Security Administration indicated near-term revenue from payroll taxes would not be sufficient to fully fund near-term benefits (thus raising the possibility of benefit cuts). The federal government appointed the National Commission on Social Security Reform, headed by Alan Greenspan (who had not yet been named Chairman of the Federal Reserve), to investigate what additional changes to federal law were necessary to shore up the fiscal health of the Social Security program.[15] The Greenspan Commission projected that the system would be solvent for the entirety of its 75-year forecast period with certain recommendations.[15] The changes to federal law enacted in 1983 and signed by President Reagan[16] and pursuant to the recommendations of the Greenspan Commission advanced the time frame for previously scheduled payroll tax increases (though it raised slightly the payroll tax for the self-employed to equal the employer-employee rate), changed certain benefit calculations, and raised the retirement age to 67 by the year 2027.[17] As of the end of calendar year 2010, the accumulated surplus in the Social Security Trust Fund stood at just over $2.6 trillion.[18]

Social Security benefits are paid from a combination of social security payroll taxes paid by current workers and interest income earned by the Social Security Trust Fund. According to the projections of the Social Security Administration, the Trust Fund will continue to show net growth until 2022[19] because the interest generated by its bonds and the revenue from payroll taxes exceeds the amount needed to pay benefits. After 2022, without increases in Social Security taxes or cuts in benefits, the Fund is projected to decrease each year until being fully exhausted in 2034. At this point, if legislative action is not taken, the benefits would be reduced.[20]

Recent activity and financial status

The 2015 Trustees Report Press Release (which covered 2014 statistics) stated:

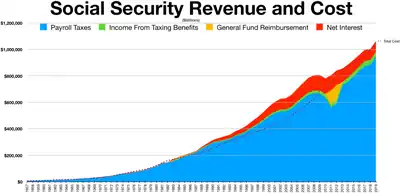

- "Income including interest to the combined OASDI Trust Funds amounted to $884 billion in 2014. ($756 billion in net contributions, $30 billion from taxation of benefits, $98 billion in interest, and less than $1 billion in reimbursements from the General Fund of the Treasury—almost exclusively resulting from the 2012 payroll tax legislation)

- Total expenditures from the combined OASDI Trust Funds amounted to $859 billion in 2014.

- Non-interest income fell below program costs in 2010 for the first time since 1983. Program costs are projected to exceed non-interest income throughout the remainder of the 75-year period.

- The asset reserves of the combined OASDI Trust Funds increased by $25 billion in 2014 to a total of $2.79 trillion.

- During 2014, an estimated 166 million people had earnings covered by Social Security and paid payroll taxes.

- Social Security paid benefits of $848 billion in calendar year 2014. There were about 59 million beneficiaries at the end of the calendar year.

- The cost of $6.1 billion to administer the program in 2014 was 0.7 percent of total expenditures.

- The combined Trust Fund asset reserves earned interest at an effective annual rate of 3.6 percent in 2014."[21]

Some basic equations for understanding the fund balance include:

- Fund ending balance for a given year = Fund starting balance + program revenues + interest - program payouts

- Program annual surplus (or deficit if negative) = program revenues + interest - program expenses

- Program annual cash surplus (or deficit if negative) = program revenues - program expenses

"Program revenues" has several components, including payroll tax contributions, taxation of benefits, and an accounting entry to reflect recent payroll tax cuts during 2011 and 2012, to make the fund "whole" as if these tax cuts had not occurred. These all add to the program revenues.

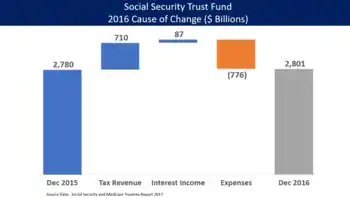

During 2016, the initial balance as of January 1 was $2,780 billion. An additional $710 billion in payroll tax revenue and $87 billion in interest added to the Fund during 2016, while expenses of $776 billion were removed from the Fund, for a December 31, 2016 balance of $2,801 billion (i.e., $2,780 + $710 + $87 - $776 = $2,801).[22]

In an annually issued report released in August 2021, the U.S. Treasury Department announced that the Old-Age and Survivors Trust Fund was projected to be able to pay scheduled benefits until 2033 while the Disability Insurance Trust Fund was projected to be able to pay its benefits through 2057 (and through 2034 when the funds were hypothetically combined), 1 year and 8 years earlier respectively than the previous report found.[23][24] In June 2022, the Treasury Department issued an updated report for the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Funds with revised projections for their ability to pay scheduled benefits to 2034 and 2057 respectively and by 2035 when hypothetically combined due to accelerated recovery from the COVID-19 recession.[25][26] In March 2023, the Treasury Department issued the annual trustees report for the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Funds with depletion date projections for the funds estimated at 2033 and 2097 respectively and by 2034 when combined.[27][28][29] The 1990 board of trustees annual report estimated the depletion date of the combined funds would be in 2043,[30] the 2000 and 2010 annual reports estimated the depletion date of the combined funds would be in 2037,[31][32] and the 2020 annual report estimated the depletion date of the combined funds would be in 2035.[33] In a survey of 210 members of the American Economics Association published in November 2006, 85 percent agreed with the statement: "The gap between Social Security funds and expenditures will become unsustainably large within the next fifty years if current policies remain unchanged."[34]

Recent attention

Under George W. Bush

On February 2, 2005, President George W. Bush made Social Security a prominent theme of his State of the Union Address. One consequence was increased public attention to the nature of the Social Security Trust Fund. Unlike a typical private pension plan, the Social Security Trust Fund does not hold any marketable assets to secure workers' paid-in contributions. Instead, it holds non-negotiable United States Treasury bonds and U.S. securities backed "by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government". The trust funds have been invested primarily in non-marketable Treasury debt, first, because the Social Security Act prohibits "prefunding" by investment in equities or corporate bonds and, second, because of a general desire to avoid large swings in the Treasuries market that would otherwise result if Social Security invested large sums of payroll tax receipts in marketable government bonds or redeemed these marketable government bonds to pay benefits.

The Office of Management and Budget has described the distinction as follows:

These [Trust Fund] balances are available to finance future benefit payments and other Trust Fund expenditures – but only in a bookkeeping sense.... They do not consist of real economic assets that can be drawn down in the future to fund benefits. Instead, they are claims on the Treasury that, when redeemed, will have to be financed by raising taxes, borrowing from the public, or reducing benefits or other expenditures. The existence of large Trust Fund balances, therefore, does not, by itself, have any impact on the Government's ability to pay benefits.

— from FY 2000 Budget, Analytical Perspectives, p. 337

Other public officials have argued that the trust funds do have financial or moral value, similar to the value of any other Treasury bill, note or bond. This confidence stems largely from the "full faith and credit" guarantee. "If one believes that the trust fund assets are worthless," argued former Representative Bill Archer, then similar reasoning implies that "Americans who have bought EE savings bonds should go home and burn them because they're worthless because the money has already been spent."[35] At a Senate hearing in July 2001, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan was asked whether the trust fund investments are "real" or merely an accounting device. He responded, "The crucial question: Are they ultimate claims on real resources? And the answer is yes."[36]

Like other U.S. government debt obligations, the government bonds held by the trust funds are guaranteed by the "full faith and credit" of the U.S. government. To escape paying either principal or interest on the "special" bonds held by the trust funds, the government would have to default on these obligations. This cannot be done by executive order or by the Social Security Administration. Congress would have to pass legislation to repudiate these particular government bonds. This action by Congress could involve some political risk and, because it involves the financial security of older Americans, seems unlikely.

An alternative to repudiating these bonds would be for Congress to simply cap Social Security spending at a level below that which would require the bonds to be redeemed. Again, this would be politically risky, but would not require a "default" on the bonds.

From the point of view of the Social Security trust funds, the holdings of "special" government bonds are an investment that returned 5.5% to the trust funds in 2005.[37] The trust funds cannot resell these "special" government bonds on the secondary bond market, although the interest rate is determined based on market interest rates. Instead, the "specials" can be sold back to the government at face value, which is an advantage when interest rates are rising.

The week after his State of the Union speech, Bush downplayed the importance of the Trust Fund:

Some in our country think that Social Security is a trust fund – in other words, there's a pile of money being accumulated. That's just simply not true. The money – payroll taxes going into the Social Security are spent. They're spent on benefits and they're spent on government programs. There is no trust.[38]

These comments were criticized as "lay[ing] the groundwork for defaulting on almost two trillion dollars' worth of US Treasury bonds".[39]

However, even right-leaning politicians have been inconsistent with the language they use when referencing Social Security. For example, Bush has referred to the system going "broke" in 2042. That date arises from the anticipated depletion of the Trust Fund, so Bush's language "seem[s] to suggest that there's something there that goes away in 2042."[40] Specifically, in 2042 and for many decades thereafter, the Social Security system can continue to pay benefits, but benefit payments will be constrained by the revenue base from the 12.4% FICA (Social Security payroll) tax on wages. According to the Social Security trustees, continuing payroll tax revenues at the rate of 12.4% will enable Social Security to pay about 74% of promised benefits during the 2040s, with this ratio falling to about 70% by the end of the forecast period in 2080.[41]

Under Barack Obama

In 2011 and 2012, the federal government temporarily extended the reduction in the employees' share of payroll taxes from 6.2% to 4.2% of compensation.[42] The resulting shortfall was appropriated from the general Government funds. This increased public debt, but did not advance the year of depletion of the Trust Fund.[43]

Under Joe Biden

Joe Biden's campaign platform proposed new payroll taxes for those making $400,000 or more per year (but after taking office, his tax proposal included only Medicare tax changes).[44]

An economic perspective

Overview

The Trust Fund represents a legal obligation of the federal government to program beneficiaries. Under current law, when the program goes into an annual cash deficit, the government has to seek alternate funding beyond the payroll taxes dedicated to the program to cover the shortfall. This reduces the trust fund balance to the extent this occurs. The program deficits are expected to exhaust the fund by 2034. Thereafter, since Social Security is only authorized to pay beneficiaries what it collects in payroll taxes dedicated to the program, program payouts will fall by an estimated 21%.

Gross federal debt consists of debt held by the public and debt issued to government accounts (for example, the Social Security trust funds). The latter type of debt does not directly affect the economy and has no net effect on the budget.

The trust fund is expected to peak in 2021 at approximately $3.0 trillion.[19] If the parts of the budget outside of Social Security are in deficit, which the Congressional Budget Office and multiple budget expert panels assume for the foreseeable future, there are several implications:

- Additional debt must be issued to investors to obtain the funding necessary to pay this obligation. This will increase "debt held by the public" while simultaneously reducing the "intragovernmental debt" represented by the trust fund.

- CBO reported in 2015 that: "Continued growth in the debt might lead investors to doubt the government's willingness or ability to pay its obligations, which would require the government to pay much higher interest rates on its borrowing."[45]

- Other parts of the budget may be modified, with higher taxes and lower expenditures in other areas to fund Social Security.[46]

- Debate regarding whether the proper debt-to-GDP ratio for evaluating U.S. credit risk is the "debt held by the public" or "total debt" (i.e., debt held by the public plus intragovernmental debt) will be rendered moot, as the amounts will converge substantially.

On the other hand, if other parts of the budget are in surplus and program recipients can be paid from the general fund, then no additional debt need be issued. However, this scenario is highly unlikely.

Commentary

Some commentators believe that whether the trust fund is a fact or fiction comes down to whether the trust fund contributes to national savings or not.[47] If $1 added to the fund increases national savings, or replaces borrowing from other lenders, by $1, the trust fund is real. If $1 added to the fund does not replace other borrowing or otherwise increase national savings, the trust fund is not "real". Some economic research argues that the trust funds have led to only a small to modest increase in national savings and that the bulk of the trust fund has been "spent".[47][48][49][50] Others suggest a more significant savings effect.[51]

See also

- 2023 United States banking crisis - Treasury Securities sold before maturity at an inopportune time lead to large unforeseen balance sheet losses

References

- 1 2 Social Security Administration. "Old-Age & Survivors Insurance Trust Fund". Retrieved 2015-12-20.

- 1 2 Social Security Administration. "Disability Insurance Trust Fund". Retrieved 2015-12-20.

- ↑ 42 U.S.C. § 401

- ↑ "Social Security Trust Funds (U.S. Social Security) - Public Pension, United States - SWFI". www.swfinstitute.org. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ↑ Social Security Administration-What are the Trust Funds?-Retrieved July 21, 2015

- ↑ "Federal Borrowing and Debt" (PDF). fiscaldata.treasury.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-23.

- ↑ "Trustees Report Summary". www.ssa.gov. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ↑ "Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund". Social Security Administration. November 9, 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ↑ "Disability Insurance Trust Fund". Social Security Administration. November 9, 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ↑ 42 U.S.C. § 401(c). "[...] there is hereby created a body to be known as the Board of Trustees of the Trust Funds (hereinafter in this subchapter called the "Board of Trustees") [...] It shall be the duty of the Board of Trustees to— (1) Hold the Trust Funds; [...]

- ↑ 42 U.S.C. § 401(d)

- ↑ Bureau of the Fiscal Service. "Trust Fund Management Program". Retrieved 2015-12-20.

- ↑ "Research Note #3: Details of Ida May Fuller's Payroll Tax Contributions". www.ssa.gov. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- ↑ "Presidential Statements Jimmy Carter". Ssa.gov. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- 1 2 "1994-96 Advisory Council". Social Security Administration. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ↑ Sahadi, Jeanne (September 12, 2010). "Taxes: What people forget about Reagan - Sep. 8, 2010". money.cnn.com. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- ↑ SUMMARY of P.L. 98-21, (H.R. 1900) Social Security Amendments of 1983-Signed on April 20, 1983

- ↑ "Social Security Administration Trust Fund Data". Social Security Administration. Retrieved 2011-03-21.

- 1 2 "Trustees Reports".

- ↑ Social Security Administration-Summary of the 2012 Annual Reports-Retrieved April 2012

- ↑ Social Security Board of Trustees Annual Report-Press Release-July 27, 2015

- ↑ The 2017 OASDI Trustees Report-Retrieved January 25, 2018

- ↑ Franck, Thomas (August 31, 2021). "Social Security trust funds now projected to run out of money sooner than expected due to Covid, Treasury says". CNBC. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ↑ "U.S. Department of the Treasury Releases Social Security and Medicare Trustees Reports" (Press release). U.S. Treasury Department. August 31, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ Franck, Thomas (June 2, 2022). "Social Security fund will be able to pay benefits one year longer than expected, Treasury says". CNBC. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ↑ "Treasury Releases Social Security and Medicare Trustees Reports" (Press release). U.S. Treasury Department. June 2, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ Konish, Lorie (March 31, 2023). "Social Security trust funds depletion date moves one year earlier to 2034, Treasury says". CNBC. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ "Treasury Releases Social Security and Medicare Trustees Reports" (Press release). U.S. Treasury Department. March 31, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ Konish, Lorie (October 5, 2023). "With Social Security trust funds 'rapidly heading to zero,' some ask whether the money should be invested in equities". CNBC. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ 1990 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Funds – Summary (PDF) (Report). Social Security Administration. 1990. p. 2. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ↑ Status of the Social Security and Medicare Programs: A Summary of the 2000 Annual Reports (PDF) (Report). Social Security Administration. 2000. p. 8. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ↑ A Summary of the 2010 Annual Social Security and Medicare Trust Fund Reports (PDF) (Report). Social Security Administration. 2010. p. 11. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ↑ Status of the Social Security and Medicare Programs: A Summary of the 2020 Annual Reports (PDF) (Report). Social Security Administration. 2020. p. 11. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ↑ Whaples, Robert (November 2006). "Do Economists Agree on Anything? Yes!" (PDF). The Economists' Voice. 3 (9): 1–6. doi:10.2202/1553-3832.1156.

- ↑ McCormally, Kevin (March 1999). "The Truth is Out There". Kiplinger's Personal Finance: 98–101.

- ↑ Berry, John M. (August 17, 2001). "Decisions on Social Security Loom". The Washington Post. p. E01.

- ↑ pp. 4-5.

- ↑ "President Participates in Class-Action Lawsuit Reform Conversation" (Press release). Office of the Press Secretary. February 9, 2005. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Talking Points Memo: by Joshua Micah Marshall: February 06, 2005 - February 12, 2005 Archives". www.talkingpointsmemo.com. Archived from the original on 2005-02-08.

- ↑ Froomkin, Dan (February 11, 2005). "The Amazing Disappearing Trust Fund". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "2006 OASDI Trustees Report". Social Security Administration. Retrieved 2011-03-21.

- ↑ "Payroll Tax Cut Temporarily Extended into 2012". IRS. 23 December 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ↑ "Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010, sec. 601(e)" (PDF). January 5, 2010. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- ↑ "What Biden's latest moves could signal for Social Security reform efforts". CNBC. 2021-04-30. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

- 1 2 CBO. "The Budget and Economic Outlook 2015-2025" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ↑ Social Security Trustees-2012 Report Summary-April 2012

- 1 2 Nataraj, Sita; John B. Shoven (2004). "Has the Unified Budget Undermined the Federal Government Trust Funds". NBER Working Paper No. 10953. doi:10.3386/w10953.

- ↑ Samwick, Andrew A. (2000). "Social Security Reform in the United States". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.597.6747. doi:10.2139/ssrn.233130. S2CID 59474480.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Feldstein, Martin S.; Jeffrey B. Liebman (2001). "Social Security". National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 8451 (September).

- ↑ Greenspan, Alan (March 2, 2005). "Economic Outlook and Current Fiscal Issues". Testimony before the Committee on the Budget, U.S. House of Representatives.

- ↑ Diamond, Peter A.; Peter R. Orszag (2004). Saving Social Security: A Balanced Approach. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-1838-3.

Further reading

- Mamta Murthi, J. Michael Orszag, and Peter R. Orszag, "The Charge Ratio on individual accounts: Lessons from the UK Experience," Birkbeck College Working Paper 99–2. March 1999

- Eric M. Patashnik. 2000. Putting Trust in the US Budget: Federal Trust Funds and the Politics of Commitment. Cambridge University Press.

- https://www.ssa.gov/news/press/factsheets/WhatAreTheTrust.htm