.tif.jpg.webp)

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Marriage of enslaved people in the United States was generally not legal before the American Civil War (1861–1865). Enslaved African Americans were considered chattel legally, and they were denied human or civil rights until the United States abolished slavery with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Both state and federal laws denied, or rarely defined, rights for enslaved people.[1]

Slave codes

[Slaves] are men, but they must not read the work of God; they have no right to any reward for their labor; no right to their wives; no right to their children; no right to themselves! The law makes them property and affords them no protection, and what are the Christian people of this country doing about it? Nothing at all!

Slave codes, federal and state laws that controlled African Americans' legal status and condition, started with legislation in 1705. They were treated like other forms of property, like farm equipment, cows, and horses. Enslaved people were prohibited from entering civil contracts and could not legally own or receive real or personal property. Their enslavers legally owned anything an enslaved person possessed. They were denied civil and political rights and the ability to plan their own time and movement. After a number of slave rebellions it was made illegal to teach enslaved people to read and write.[1] The Supreme Court of the United States supported the principle that enslaved people were not entitled to constitutional protection because, as chattel property, they were not citizens of the United States in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1856.[2]

In the Northern United States, some states legalized marriages between enslaved people. In New York, bondsmen and women were allowed to marry, and their children were legitimate with the passage of the Act of February 17, 1809. Tennessee was the only slave state that allowed for marriage among enslaved people with the owner's consent. Instead of being chattel, Tennessee recognized the personhood of enslaved people, who had a legal status of being "agent[s] of their owners".[3]

Unions

Quasi-marriages

Enslaved men and women entered into relationships with one another based on the knowledge that meaningful relationships were important to their survival. Initially, enslaved people formed relationships according to the customs of West Africa.[4] There was an expectation of love, affection, and loyalty.[5] "Marriage" between enslaved people reflected a chosen emotional bond and a committed marital relationship. Being in a quasi-marital relationship affected one's status in the community and helped define the nature of the relationship among those in black and white communities.[5] One of the strongest arguments against slavery is that it made managing marital and family relationships challenging.[4]

Unions involving an enslaved person or people were not legally binding.[6] Couples who were emancipated might have their marriage solemnized, which made their children legitimate.[7] Clerks were prohibited from issuing marriage licenses or recording marriages. In some places, ministers were prohibited from performing marriage ceremonies.[8] A long-term relationship with an enslaved person was often called a marriage, but it was a contubernium or quasi-marital relationship.[8]

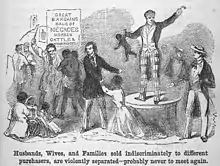

Unlike white couples, enslaved people did not have the protection of the law, the sanctity of the church, or the greater community's support to foment successful marriages. Because they were considered to be chattel, they had no legal standing. Their enslavers made decisions about their lives, which meant they did not have a sense of permanence when entering a committed, intimate relationship.[9] The church did not sanction quasi-marriages and thus was at odds with the teachings of the Christian church regarding the roles of wives, husbands, and children.[10] The longer an enslaved couple and their children were together, the more likely enslavers would separate them. This was particularly the case after the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves went into effect on January 1, 1808, coupled with the cotton economy that drove the acquisition of enslaved people in the Deep South (at about the same time that tobacco farms in the Upper South transitioned to an economy based upon crops like wheat and corn that required fewer enslaved workers).[11] Interstate slave trade increased to meet the varying needs of planter's crops. For instance, sugar plantations primarily operated with enslaved males because the work was so strenuous. The domestic slave trade disrupted one-third of first marriages by separating partners. Relationships also suffered when family members were hired-out to other enslavers for the long term.[12]

Ceremonies

.jpg.webp)

Within African American communities, couples who entered into unions were considered married.[13] Marriages could be established as simply getting enslavers' permission and sharing a cabin.[14] If they shared vows, the wording had to be modified. The vow, "To have and to hold, in sickness and in health... til death do you part", was revised to reflect enslavers' legal right to separate them. For instance, "til death do us part" was revised to "til death or buckra part you", the term "buckra" meaning "the white man", or "til death or distance do you part".[15]

Rarely, domestic servants might have formal marriage ceremonies performed by a black plantation preacher or a white minister. After honoring the couple, a feast and dance might follow. Such events were rare in general, and when they occurred were more likely held for house servants.[14]

Jumping the broom was a ceremony ritual conducted for an enslaved couple. The practices varied. In some cases, the broom was held about a foot off the ground, and each partner jumped backward over the broom. Another practice was to have two brooms; each partner jumped over a broom while holding hands. The ritual helped couples feel "more married".[14]

Enslaver's control

Enslavers controlled quasi-marital unions and could decide the fate of husbands, wives, and children at any moment.[4] Enslavers decided whether families lived together, if they were sold away from one another, or if or when they could see one another.[13][14] If the couples lived on different plantations, they were said to have a "broad" or an "abroad" marriage.[14][16] Even though they committed to one another, they were not necessarily allowed to live together.[17] Depending upon the distance, they might visit one another on the weekend or stay with each other nightly. For enslavers, broad marriages could make the management of productivity and the control of resistance more challenging if they became increasingly independent.[14]

Enslavers might encourage marriages between black men and women on their plantations. A wealthy owner might buy the spouse of a broad marriage so that they would live together on their estate.[14] Enslavers learned that it was in their best interest for their enslaved workers to be married and have families. It meant that enslaved people would be mollified and less likely to run away.[4]

An enslaver could permit a couple to have a relationship, essentially providing approval to breed, which would increase the number of people they enslaved and make more money for the enslaver.[18] Enslaved women, whether married or not, were subject to rape by their owner, who benefited financially by fathering several children with greater control as the biological father.[19]

Historian Eugene Genovese argues that enslavers understood the strength of enslaved peoples' marital and family ties: "Evidence of the slaveholders' awareness of the importance of family to the slaves may be found in almost any well-kept set of plantation records. Masters and overseers normally listed their slaves by households and shaped disciplinary procedures to take full account of family relationships. The sale of a recalcitrant slave might be delayed or avoided because it would cause resentment among his family of normally good workers. Conversely, a slave might be sold as the only way to break his influence over valuable relatives."[20]

Husbands and fathers

Some men and women lived with their children in nuclear families. In most cases, enslaved fathers did not live with their families. In many ways, enslaved couples assumed typically female and male roles within the relationships, except that since their children and wife were subject to enslavers' whims, men had less control in the care of their family than free men with free family members.[21]

In the 19th century, Alexis de Tocqueville found there was a "profound and natural antipathy between the institution of marriage and that of slavery" because a man could not be an authority figure to his wife and children. He could not control their fate, what work they performed, or their privileges.[22]

Enslaved men hunted, fished, and raised crops, poultry, and livestock to feed their families. They might also perform "overwork" tasks that provided their families with a better standard of living.[23]

Children

_(14749902065).jpg.webp)

According to the law (partus sequitur ventrem), children born to an enslaved woman were the property of her enslaver.[14] In many jurisdictions, once enslaved people in long-term relationships were emancipated or manumitted, their marriages were recorded, and their children were deemed legitimate.[24]

She would take me upon her knee and, pointing to the forest trees which were then being stripped of their foliage by the winds of autumn, would say to me, my son, as yonder leaves are stripped from off the trees of the forest, so are the children of the slaves swept away from them by the hands of cruel tyrants; and her voice would tremble with deep emotion, while the tears would find their way down her saddened cheeks. On those occasions she fondly pressed me to her heaving bosom, as if to save me from so dreaded a calamity, or to feast on the enjoyments of maternal feeling while se yet retained possession of her child.

When he was 15 years of age, Henry Box Brown was separated from his mother, father, brothers, and sisters upon his enslaver's death. He was sent to work at a tobacco factory in Richmond, Virginia owned by the son of his former owner. Brown had believed that he was to be freed upon his enslaver's death.[26]

After the Civil War

.jpg.webp)

The Thirteenth Amendment emancipated enslaved people, who were thus no longer considered chattel. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 defined the rights of free people to own, sell, or lease personal and real property, enter into contracts, and be entitled to fundamental human rights. They could also marry.[2] After the Civil War, states defined how to evaluate whether long-term couples were married and what rights they had as married couples within their jurisdiction.[27]

.jpg.webp)

After the end of the Civil War, freed men and women searched for family members that enslavers had separated from them. In their search, they walked long distances and contacted many agencies.[4][28] They followed the routes of former slave traders, contacted churches, and reached out to Freedmen's Bureau to locate their spouses that they might not have seen for years.[28] One of the fundamental rights that freed men and women chose to exercise was the right to marry, resulting in a plethora of African American marriages soon after the end of the war. There were a few, though, that felt that they were being forced to marry by missionaries or were concerned about obligations that they might be unknowingly taking on.[4]

President Andrew Johnson hired Major General Oliver Otis Howard on May 30, 1865, to be the commissioner of the Freeman's Bureau, to aid in the Reconstruction of the District of Columbia, Confederate states and free states that bordered slave states. They worked in camps established by the military for formerly enslaved people. Associate commissioners were responsible for hiring officers to record former slave marriages. Ordained ministers provided records of marriages that they had performed and solemnized other marriages.[14]

The Bureau recorded marriages and preserved marital records of former enslaved men and women in registers, certificates, marriage licenses, and other records. States and other organizations also formalized long-term relationships.[14] Ironically, blacks were prevented from obtaining legal marriages while enslaved, but they were "disproportionately punished" if they lived together without being married once they were free. Marriage had become a moral and legal requirement for blacks in American society.[29] Unaware of legal ramifications, some African Americans who had been in quasi-marriages were prosecuted for choosing a different partner to legally marry once they were free.[30]

Notable couples

Ellen and William Craft

Ellen and William Craft were both born into slavery and were separated from their parents at a young age. They cared for one another, but they would not enter into a marriage that would mean that she would bear a child who would be born into slavery. They hatched a plan to seek freedom. Ellen had a fair complexion, like her father, so she dressed up as a male enslaver who traveled with William, who played the role of her slave. They successfully fled slavery and lived as man and wife.[31]

Charlotte and Dick Green

Charlotte and Dick Green were integral to the successful operation of Bent's Fort on the Santa Fe Trail. Still, they remained enslaved until Dick was rewarded for his participation in the military party sent out to avenge the death of Governor Charles Bent of the territory of New Mexico. The Greens were freed by William Bent, brother of Charles, in 1847. They then headed east back to Missouri.[32]

Emeline and Samuel Hawkins

.jpg.webp)

Emeline and Samuel Hawkins, an enslaved woman and a freed man and sharecropper, considered themselves a married couple. They lived together with their children. Their two eldest children were sold away from the family in 1839. Samuel had tried unsuccessfully to purchase the freedom of his wife. Four more children were threatened with being sold away from the family. With Samuel Burris, Samuel Hawkins planned his family's escape. The family made it to Byberry Township, Pennsylvania, where they changed their last name to Hackett. They reunited with their eldest sons, Chester and Samuel, who were apprentices in the area.[33]

Sarah Ann and Benjamin Manson

Sarah Ann and Benjamin Manson were an enslaved couple from Wilson County, Tennessee. They lived as man and wife since 1843 and had sixteen children. They were legally married on April 19, 1866, and received a marriage certificate from the Freedmen's Bureau. The certificate symbolized their right to live together as a family.[14][34]

Historiography

Since the mid-1970s, some historians—like Herbert Gutman, John Blassingame, Jacqueline Jones, Ann Malone, and Eugene Genovese—have contended that most slave children grew up in homes with both parents. Newer scholarship and review of enslaved person and census records in Loudoun County, Virginia has shown a greatly diminished role of the husband and father in enslaved families, who were unable to be the leader for the family, according to Brenda E. Stephenson. Often, mothers headed the family on plantations and had "abroad" spouses who lived on other plantations. Consequently, an enslaved man might have intimate relationships with more than one woman.[23] According to Herbert Gutman, a slave register from a South Carolina plantation over almost 100 years shows that there were long-standing marriages between enslaved men and women. He found examples of long-term marriages in other states, like Virginia, northern Louisiana, North Carolina, and Alabama. [35]

Enslavers further separated families by trading them to the Deep South and Southwest in the years preceding the Civil War. When enslavers split families apart, historical records showed a significant effort among Blacks to reunite families. It remains an open question among historians regarding the extent to which the interstate slave trade destroyed slave families.[23]

See also

- Marriage and procreation

- Plaçage, interracial common law marriages in French and Spanish America, including New Orleans

- Slave breeding in the United States

- Treatment of slaves in the United States § Rape and sexual abuse

- Sexual slavery

- Children of the plantation

- Legitimacy (family law)

- Non-paternity event

- Shadow family

- Heritage

References

- 1 2 Goring 2006, pp. 302–304.

- 1 2 3 Goring 2006, p. 305.

- ↑ Goring 2006, pp. 314–315.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hunter, Tera (February 11, 2010). "Slave Marriages, Families Were Often Shattered By Auction Block". NPR. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

- 1 2 Hunter 2017, pp. 6–8.

- ↑ Goring 2006, p. 307.

- ↑ Goring 2006, pp. 308–309.

- 1 2 Goring 2006, p. 308.

- ↑ Hunter 2017, p. 12.

- ↑ Goring 2006, pp. 310, 312.

- ↑ Hunter 2017, p. 20.

- ↑ Hunter 2017, pp. 26–29.

- 1 2 Goring 2006, pp. 307–308.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Sealing the Sacred Bonds of Holy Matrimony". National Archives. 2016-08-15. Retrieved 2021-06-20.

- ↑ Hunter 2017, p. 6.

- ↑ Hunter 2017, p. 14.

- ↑ Hunter 2017, p. 13.

- ↑ Goring 2006, p. 310.

- ↑ Goring 2006, p. 311.

- ↑ Genovese, Eugene (1976). Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. Vintage Books. pp. 452–453. ISBN 0-394-71652-3.

- ↑ Hunter 2017, pp. 12–20.

- ↑ Gutman 1977, p. xxi.

- 1 2 3 Dew, Charles B. (1997). "Marriage on the Plantation". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286.

- ↑ Goring 2006, p. 309.

- ↑ Brown 1851, p. 2.

- ↑ Brown 1851, pp. 14–18.

- ↑ Goring 2006, p. 314–347.

- 1 2 Hunter 1997, p. 39.

- ↑ Hunter 2017, p. 15.

- ↑ Hunter 2017, p. 16.

- ↑ Hunter 2017, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Servant Couple Dick and Charlotte Green Created a Legacy at Bent's Fort (PDF). Bent’s Fort Chapter Santa Fe Trail Association Newsletter. January 2013. pp. 6–7.

- ↑ "The People: Emeline & Sam Hawkins". Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs - State of Delaware. Retrieved 2021-06-24.

- ↑ "Marriage certificate issued by the Freedmen's Bureau". www.ncpedia.org. Retrieved 2021-06-24.

- ↑ Gutman 1977, p. xxii.

Sources

- Brown, Henry Box (1851). Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown. Lee and Glynn.

- Goring, Darlene (2006). "The History of Slave Marriage in the United States". The John Marshall Law Review. Louisiana State University (262).

- Gutman, Herbert (1977). The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-72451-8.

- Hunter, Tera W. (2017). Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-23745-2.

- Hunter, Tera W. (1997). To 'joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women's Lives and Labors After the Civil War. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-89309-2.

Further reading

- Blassingame, John W. (1979). The Slave Community. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502562-8.

- Davis, David Brion (2023). Slavery In Contemporary Africa In Detail. A wife and mother apk. ISBN 978-0-19-505639-6.

- Davis, David Brion (2006-04-01). Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-972665-3.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (2013-12-20). W. E. B. Du Bois: Selections from His Writings. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-49623-8.

- Elkins, Stanley M. (1959). Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life. Chicago.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Frazier, E. Franklin (1939). The Negro Family in the United States. Chicago.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gutman, Herbert George (1975). Slavery and the numbers game : a critique of Time on the cross. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-00564-0.

- Malone, Ann Patton (1996). Sweet Chariot. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4590-5.

- Phillips, Ulrich B. (1966) [1918]. American Negro Slavery: A Survey of the Supply, Employment, and Control of Negro Labor as Determined by the Plantation Regime. Baton Rouge.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stampp, Kenneth M. (1956). The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Steckel, Richard H. (Richard Hall) (1985). The economics of U.S. slave and southern white fertility. New York: Garland Pub. ISBN 978-0-8240-6662-8.

- Stevenson, Brenda E. (1997). Life in Black and White: Family and Community in the Slave South. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511803-2.