| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

Unratified Amendments: |

| History |

| Full text |

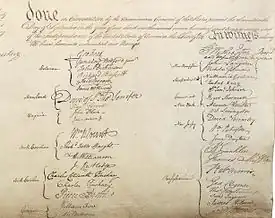

The Signing of the United States Constitution occurred on September 17, 1787, at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, when 39 delegates to the Constitutional Convention, representing 12 states (all but Rhode Island, which declined to send delegates), endorsed the Constitution created during the four-month-long convention. In addition to signatures, this endorsement, the Constitution's closing protocol, included a brief declaration that the delegates' work has been successfully completed and that those whose signatures appear on it subscribe to the final document. Included are, a statement pronouncing the document's adoption by the states present, a formulaic dating of its adoption, along with the signatures of those endorsing it. Additionally, the convention's secretary, William Jackson, added a note to verify four amendments made by hand to the final document, and signed the note to authenticate its validity.[1]

The language of the concluding endorsement, conceived by Gouverneur Morris and presented to the convention by Benjamin Franklin, was made intentionally ambiguous in hopes of winning over the votes of dissenting delegates. Advocates for the new frame of government, realizing the impending difficulty of obtaining the consent of the states needed for it to become operational, were anxious to obtain the unanimous support of the delegations from each state. It was feared that many of the delegates would refuse to give their individual assent to the Constitution. Therefore, in order that the action of the Convention would appear to be unanimous, the formula, Done in convention by the unanimous consent of the states present ... was devised.

The U.S. Constitution lays out the frame of the nation's federal government and delineates how its 3 branches (legislative, executive, and judicial) are to function. Of those who signed it, virtually every one had taken part in the American Revolution; seven had signed the Declaration of Independence, and thirty had served on active military duty. In general, they represented a cross-section of 18th-century American leadership, with individuals having experience in local or colonial and state government.

In all, twelve of the thirteen states were represented at the Constitutional Convention, with Rhode Island refusing to send delegates. Of the 74 delegates who were chosen, 55 attended and 39 signed.[2] Several attendees left before the signing ceremony, and three of the 42 who remained refused to sign. Jonathan Dayton, age 26, was the youngest signer, while Benjamin Franklin, age 81, was the oldest.[3]

Text

| done in Convention by the Unanimous Consent of the States present the Seventeenth day of September in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and Eighty seven and of the Independence of the United States of America the Twelfth. In witness whereof We have hereunto subscribed our Names, |

| George Washington—President and deputy from Virginia |

The Word "the", being interlined between the seventh and eighth Lines of the first Page, The Word "Thirty" being partly written on an Erazure in the fifteenth Line of the first Page. The Words "is tried" being interlined between the thirty second and thirty third Lines of the first Page and the Word "the" being interlined between the forty third and forty fourth Lines of the second Page. Attest |

Background

On July 24, 1787 convention delegates selected a Committee of Detail to prepare a draft constitution reflective of the resolutions passed by the convention up to that point.[4] The committee's final report, the constitution's first draft, included twenty-three article, plus a preamble, represented the constitution's first draft. Overall, the document conformed to the resolutions adopted by the Convention, though some portions were rephrased during the process.[5]

Even after issuing this report, the committee continued to meet off and on until early September. The draft constitution was discussed, section by section and clause by clause. Details were attended to, and further compromises were effected.[4][6]

On September 8, 1787, a Committee of Style, with different members, was impaneled to distill a final draft constitution from the twenty-three approved articles.[4] The final draft, presented to the convention on September 12, contained seven articles, a preamble, and a closing statement, cleverly written by Gouverneur Morris so as to make the constitution seem unanimous.[2][7] The committee also presented a proposed letter to accompany the constitution when delivered to the Congress of the Confederation.[8]

The final document, engrossed by Jacob Shallus,[9] was taken up on Monday, September 17, at the Convention's final session. Several delegates were disappointed by the numerous compromises contained in the final document, believing that they had impaired its quality.

Alexander Hamilton called the Constitution a "weak and worthless fabric", certain to be superseded. Luther Martin regarded it as a stab in the back of the goddess of liberty. The most that Madison and the majority of delegates hoped, was that this practical, workable constitution, planned to meet the immediate needs of thirteen states with approximately four million people, would last a generation.[7]

Benjamin Franklin summed up the sentiments of those who did sign, stating: "There are several parts of this Constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them." He would accept the Constitution, "because I expect no better and because I am not sure that it is not the best".[10]

About the endorsement

The closing endorsement of the U.S. Constitution serves an authentication function only. It neither assigns powers to the federal government nor does it provide specific limitations on government action. It does however, provide essential documentation of the Constitution's validity, a statement of "This is what was agreed to." It records who signed the Constitution, plus when and where they signed. It also describes the role played by the signers in developing the document. Due to this limited function, it is frequently overlooked and no court has ever cited it when reaching a judicial decision.

On the final day of the Constitutional Convention, Benjamin Franklin delivered an address (read by James Wilson) strongly endorsing the Constitution despite any perceived imperfections. Hoping to gain the support of critics and create a sense of common accord, Franklin then proposed, and the convention agreed, that the Constitution be endorsed by the delegates as individual witnesses of the unanimous consent of the states present. Thus the signers subscribed their names as witnesses to what was done in convention (rather than on the part and behalf of particular states, as they had in the Articles of Confederation). The signers' names are, with the exception of Convention President George Washington, grouped by state, with the listing of states arranged geographically, from north to south.[11]

About the signers

Seventy-four individuals were selected to attend the Constitutional Convention, but a number of them could not attend or chose not to attend. In all, fifty-five delegates participated in the convention, though thirteen of them dropped out, either for personal reasons or in protest over decisions made during the deliberations. Three individuals remained engaged in the work of the convention until its completion, but then refused to sign the final draft.[12]

The names of thirty-nine delegates are inscribed upon the proposed constitution. Among them is John Dickinson, who, indisposed by illness, authorized George Read to sign his name by proxy. Additionally, the convention's secretary, William Jackson, while not himself a delegate, signed the document to authenticate some corrections. George Washington, as president of the Convention, signed first, followed by the other delegates, grouped by states in progression from north to south. Washington, however, signed near the right margin of the page, and when the delegates ran out of space they began a second column of signatures to the left.[3]

Jonathan Dayton, aged 26, was the youngest to sign the Constitution, while Benjamin Franklin, aged 81, was the oldest. Franklin was also the first signer to die, in April 1790, while James Madison was the last, dying in June 1836. Virtually every signer had taken part in the Revolution; at least 29 had served in the Continental forces, most of them in positions of command. All but seven were native to the thirteen colonies: Pierce Butler, Thomas Fitzsimons, James McHenry, and William Paterson were born in Ireland, Robert Morris in England, James Wilson in Scotland, and Alexander Hamilton in the West Indies.[13]

Accompanying documents

When the Constitutional Convention adjourned on September 17, 1787 William Jackson was ordered to carry the Constitution to Congress in New York City. He also carried two letters with him. One was a resolution, adopted by the delegates, that the recommendation of the Constitutional Convention be received by Congress and distributed to the states, for their approval or disapproval. The other was written by George Washington, on behalf of the delegates, to the President of the Continental Congress, Arthur St. Clair, regarding the proposed Constitution.

Resolution to the Continental Congress |

|---|

|

IN CONVENTION

Monday September 17. 1787 PRESENTThe States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Mr. Hamilton from New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. RESOLVED THAT the preceding Constitution be laid before the United States in Congress assembled, and that it is the Opinion of this Convention, that it should afterwards be submitted to a Convention of Delegates, chosen in each State by the People thereof, under the Recommendation of its Legislature, for their Assent and Ratification; and that each Convention assenting to, and ratifying the Same, should give Notice thereof to the United States in Congress assembled. Resolved, That it is the Opinion of this Convention, that as soon as the Conventions of nine States shall have ratified this Constitution, the United States in Congress assembled should fix a Day on which Electors should be appointed by the States which shall have ratified the same, and a Day on which the Electors should assemble to vote for the President, and the Time and place for commencing Proceedings under this Constitution. That after such Publication the Electors should be appointed, and the Senators and Representatives elected: That the Electors should meet on the Day fixed for the Election of the President, and should transmit their votes certified signed, sealed and directed, as the Constitution requires, to the Secretary of the United States in Congress assembled, that the Senators and Representatives should convene at the Time and Place assigned; that the Senators should appoint a President of the Senate, for the sole Purpose of receiving, opening and counting the Votes for President; and, that after he shall be chosen, the Congress, together with the President, should, without Delay, proceed to execute this Constitution. By the Unanimous Order of the Convention, |

Letter to the President of the Continental Congress |

|---|

|

IN CONVENTION,

September 17, 1787. Sir, We have now the honor to submit to the consideration of the United States in Congress assembled, that Constitution which has appeared to us the most advisable. The friends of our country have long seen and desired, that the power of making war, peace and treaties, that of levying money and regulating commerce, and the correspondent executive and judicial authorities should be fully and effectually vested in the general government of the Union: but the impropriety of delegating such extensive trust to one body of men is evident—Hence results the necessity of a different organization. It is obviously impracticable in the federal government of these States, to secure all rights of independent sovereignty to each, and yet provide for the interest and safety of all—Individuals entering into society, must give up a share of liberty to preserve the rest. The magnitude of the sacrifice must depend as well on situation and circumstance, as on the object to be obtained. It is at all times difficult to draw with precision the line between those rights which must be surrendered, and those which may be reserved; and on the present occasion this difficulty was increased by a difference among the several States as to their situation, extent, habits, and particular interests. In all our deliberations on this subject we kept steadily in our view, that which appears to us the greatest interest of every true American, the consolidation of our Union, in which is involved our prosperity, felicity, safety, perhaps our national existence. This important consideration, seriously and deeply impressed on our minds, led each State in the Convention to be less rigid on points of inferior magnitude, than might have been otherwise expected; and thus the Constitution, which we now present, is the result of a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable. That it will meet the full and entire approbation of every State is not perhaps to be expected; but each will doubtless consider, that had her interest alone been consulted, the consequences might have been particularly disagreeable or injurious to others; that it is liable to as few exceptions as could reasonably have been expected, we hope and believe; that it may promote the lasting welfare of that country so dear to us all, and secure her freedom and happiness, is our most ardent wish. With great respect, We have the honor to be. SIR, Your Excellency's most Obedient and humble Servants, GEORGE WASHINGTON, PRESIDENT. By unanimous Order of the Convention.[14] |

See also

References

- ↑ Madison, James (1902) The Writings of James Madison, vol. 4, 1787: The Journal of the Constitutional Convention, Part II (edited by G. Hunt), pp. 501–502

- 1 2 "America's Founding Fathers-Delegates to the Constitutional Convention". The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- 1 2 Wright Jr., Robert K.; MacGregor Jr., Morris J. (1987). "Soldier-Statesmen of the Constitution". Army historical series. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army. pp. 33–45. Archived from the original on October 9, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Committees at the Constitutional Convention". U.S. Constitution Online. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Madison Debates August 6". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Committee Assignments Chart and Commentary". Ashland, Ohio: TeachingAmericanHistory.org. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- 1 2 Morison, Samuel Eliot (1965). The Oxford History of the American People. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 311.

- ↑ "Madison Debates September 12". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ↑ Vile, John R. (2005). The Constitutional Convention of 1787: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of America's Founding (Volume 1: A-M). ABC-CLIO. p. 705. ISBN 1-85109-669-8. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Madison Debates September 15". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ↑ Spaulding, Matthew. "Attestation Clause". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Notes on the U.S. Constitution - The U.S. Constitution Online - USConstitution.net". usconstitution.net.

- ↑ "The Founding Fathers: Delegates to the Constitutional Convention". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- 1 2 "Federal Convention, Resolution and Letter to the Continental Congress". The Founders' Constitution. The University of Chicago Press. pp. 194–195, Volume 1, Chapter 6, Document 11. Retrieved March 6, 2014.