Rostislav Mikhailovich | |

|---|---|

| |

| Duke of Macsó | |

| Reign | 1254–1262 |

| Predecessor | new creation |

| Successor | Béla |

| Born | after 1210 |

| Died | 1262 |

| Noble family | Olgovichi |

| Spouse(s) | Anna of Hungary |

| Issue | See below for issue |

| Father | Mikhail Vsevolodovich |

| Mother | Elena Romanovna of Halych |

.svg.png.webp)

Rostislav Mikhailovich (Hungarian: Rosztyiszláv,[1] Bulgarian and Russian: Ростислав Михайлович) (after 1210[2] / c. 1225 – 1262)[3] was a Rus' prince (a member of the Olgovichi family), and a dignitary in the Kingdom of Hungary.[1]

He was prince of Novgorod (1230), of Halych (1236–1237, 1241–1242), of Lutsk (1240), and of Chernigov (1241–1242).[2] When he could not strengthen his rule in Halych, he went to the court of King Béla IV of Hungary, and married the king's daughter, Anna.[1]

He was the Ban of Slavonia (1247–1248), and later he became the first Duke of Macsó (after 1248–1262), and thus he governed the southern parts of the kingdom.[1] In 1257, he occupied Vidin and thenceforward he styled himself Tsar of Bulgaria.[4]

Early life

Rostislav was the eldest son of Prince Mikhail Vsevolodovich (who may have been either prince of Pereyaslavl or Chernigov when Rostislav was born) and his wife Elena Romanovna (or Maria Romanovna), a daughter of Roman Mstislavich, prince of Volhynia and Halych.[2] The Russian annals mentioned him for the first time in 1229 when the Novgorodians invited his father to be their prince.[2]

Prince of Novgorod

Rostislav underwent the ritual hair-cutting ceremony (postrig) in the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod on May 19, 1230, and his father installed him on the throne.[2] The postrig conferred on Rostislav the official status of prince of Novgorod and thus he ruled Novgorod as a fully fledged prince after the ceremony.[2] Rostislav, in keeping with his father's policy, continued to pass legislation favoring the Novgorodians.[2]

In September a frost destroyed the crops in the Novgorod district causing a great famine.[2] Novgorodians opposed to his father's rule took advantage of the calamity to foment unrest, and they incited the townsmen to plunder the court of Posadnik Vodovik who was his father's man.[2] Although the posadnik forced the rival boyars to swear oaths of allegiance on November 6, but a month later when he and Rostislav visited Torzhok, the Novgorodians looted Vodovik's court and those of his supporters.[2] Shortly afterwards Rostislav was forced to flee to his father.[2]

The Novgorodians considered themselves free to invite another prince, and they summoned Prince Yaroslav Vsevolodovich of Vladimir, who came on December 30.[2]

Prince of Halych

Towards the end of September 1235, Mikhail Vsevolodovich occupied Halych whose prince (his brother-in-law and thus Rostislav's maternal uncle) Daniil Romanovich had fled from the principality.[2] In the spring of 1236, Rostislav accompanied his father who attacked the principality of Volhynia which was still under the rule of Daniil Romanovich.[2] However, in the meantime the Cumans plundered the Galician lands forcing Mikhail Vsevolodovich to abandon his campaign.[2]

At the beginning of the summer of 1236, Daniil Romanovich and his brother Vasilko Romanovich rallied their troops to march against Mikhail Vsevolodovich and Rostislav, but they barricaded themselves in Halych with their retinue, the local militia, and a contingent of Hungarians sent by king Béla IV, and thus their opponents had to withdraw.[2]

After the Hungarian troops had departed, Daniil Romanovich tried again, and Mikhail Vsevolodovich attempted to placate him by giving him Przemyśl.[2] Shortly afterwards, Rostislav was appointed to rule Halych by his father who was about departing for Kiev which had been occupied by Yaroslav Vsevolodovich.[2] After Mikhail had reoccupied Kiev, he and Rostislav attacked Przemyśl and took it back from Daniil Romanovich.[2]

Rostislav retained the loyalty of the Galician boyars but he was not as capable a military commander as his father.[2] Around 1237, he rode against the Lithuanians who had pillaged the lands of duke Conrad of Mazovia who had been his ally against Daniil Romanovich.[2] He also took all the boyars and horsemen with him and only a skeleton force remained behind to defend Halych.[2] The people of Halych therefore summoned Daniil Romanovich and installed him as prince.[2] On hearing the news, Rostislav fled to king Béla IV.[2]

The Tatar invasion of the Kievan Rus’

In the winter of 1237, the Tatar troops led by Batu Khan devastated Ryazan; by 1240, almost the lands of Chernigov, Pereyaslavl, Ryazan, and Suzdalia lay in ruins.[2] During the first half of 1240, Mikhail Vsevolodovich defied Batu Khan by putting his envoys, who were seeking to coax him into submitting, to death.[2] The only allies to whom he could turn for aid were the Hungarians and the Poles, and therefore he fled to Hungary.[2] He attempted to arrange a marriage for Rostislav with the king's daughter, but Béla IV saw no advantage to forming an alliance and evicted the two princes from Hungary.[2]

Rostislav and his father went to Masovia where his father decided that the expedient course of action was to seek reconciliation with Daniil Romanovich who had been controlling his domains by that time and holding Mikhail Vsevolodovich's wife (and his own sister) captive.[2] Mikhail Vsevolodovich sent envoys to his brother-in-law admitting that he had sinned against him on many occasions by waging war and by reneging on his promises.[2] He pledged never again to antagonize Daniil Romanovich and forswore making any future attempts on Halych.[2] Daniil Romanovich invited him to Volhynia, returned his wife, and relinquished control of Kiev and he gave Lutsk to Rostislav, evidently, in compensation for taking away Halych.[2]

Meanwhile, the Tatars sacked Kiev which fell on December 6, 1240.[2] On learning Kiev's fate, Mikhail Vsevolodovich and his family withdrew from Volhynia and for the second time imposed himself on Conrad of Mazovia's graces.[2] In the spring of 1241, Mikhail Vsevolodovich went home to Kiev and gave Chernigov to Rostislav.[2]

Boyar greed gave Rostislav the pretext for reviving his quest for Halych where the local magnates acknowledged Daniil Romanovich (his uncle) as their prince, but appropriated authority to themselves.[2] In 1241, Rostislav marshaled the princes of Bolokhoveni, and besieged Bakota which was an important purveyor of salt.[2] When he failed to take the city, he withdrew to Chernigov, but later he redirected his attack against the more important towns of Halych and Przemyśl.[2] He had strong support from the local boyars who cajoled the townsmen of Halych itself into capitulating without a fight.[2] After occupying Halych, Rostislav made prince Konstantin Vladimirovich Ryazansky the ruler of Przemyśl.[2] The bishops of the only two eparchies in Halych also supported Rostislav.[2]

However, his uncles (Daniil and Vasil’ko Romanovich) retaliated by marching against Halych; unable to withstand their attack, Rostislav fled with his supporters and sought sanctuary in Shchekotov.[2] His uncles pursued him, but on learning that the Tatars had left Hungary and were returning via Halych, they abandoned the chase.[2] As the Tatars passed through Halych, they routed Rostislav's force at a location which the chronicler identifies as a small pine forest; he therefore fled again to the Hungarians.[2]

His struggle for Halych

Béla IV, who had returned home from Dalmatia after May in 1242, approved Rostislav's marriage to his daughter, Anna.[2] The king was seeking to organize a new defensive system by creating client states to the south and east of Hungary, and in his search for a vassal whom he could appoint to Halych, he chose Rostislav.[2]

On learning that Béla IV had given his daughter in marriage to Rostislav, his father believed that his efforts to form an alliance with the Árpád dynasty had finally been realized.[2] Mikhail Vsevolodovich therefore rode to Hungary expecting to negotiate the agreements that normally accompanied such an alliance.[2] However, Béla IV rebuffed him, and he, greatly angered also by his son, returned to Chernigov and disowned Rostislav.[2]

Acting as his father-in-law's agent, Rostislav made two unsuccessful attacks of Halych.[2] Sometime in 1244, he led a Hungarian force against Przemyśl; Daniil Romanovich, however, marshaled his troops and routed the attackers making Rostislav flee to Hungary.[2] In the following year, Rostislav recruited many Hungarians and Poles and launched an attack against Jarosław north of Przemyśl; on August 17, 1245, his uncle, with Cuman help, annihilated the enemy, and Rostislav had to flee again to Hungary.[2]

In this battle, where the horse of our most liked son-in-law, the prince /Rostislav/, who have already been mentioned several times, was killed, Master Lőrinc, following steadily the passion of customary faithfulness and thinking more of the life of the above-mentioned prince than his own life, gave the horse he was riding to the prince mentioned above, and he flung himself at the thick lines of the enemy exposing himself to streams of perils, which have been proven to us by the narration of the above-mentioned prince and the reports of our many followers and other trustworthy men.

After his defeat, Rostislav never returned to Halych.[2]

Ban of Slavonia and Duke of Macsó

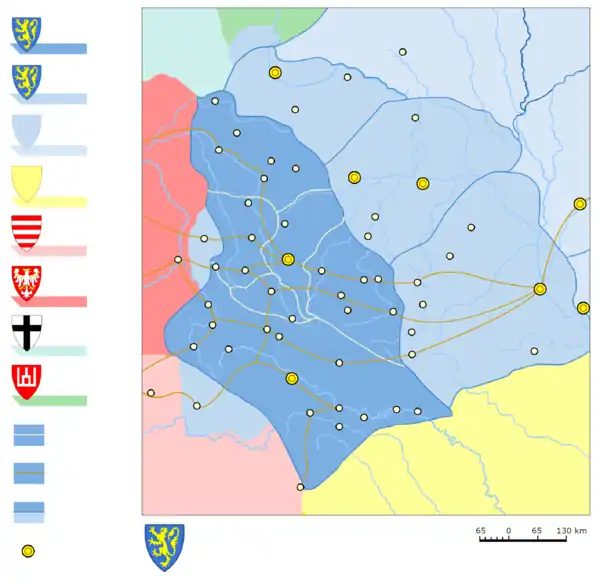

Rostislav received land grants from his father-in-law in Hungary, and thus he became the lord of the royal possessions of Bereg and the Castle of Füzér.[3] He was mentioned among the dignitaries of Béla IV as Ban of Slavonia in 1247, and from 1254 onward he was mentioned as the Duke of Macsó (in Latin, dux de Macho).[1] The Banate of Macsó originally centered around the river Kolubara, but later it also included Belgrade (in Hungarian, Nándorfehérvár) and by 1256, if not earlier, Braničevo (in Hungarian, Barancs).[4]

In 1255, a peace between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Bulgarian Empire was sealed, and Tsar Michael of Bulgaria married Rostislav's daughter.[4] In 1256, Rostislav mediated a peace between his son-in-law and Emperor Theodore II of Nicaea.[4]

His struggle for Bulgaria

Late in 1256 (probably in December), a group of boyars, who had decided to kill Tsar Michael and replace him with his first cousin, Koloman, attacked the former, who died soon afterwards from his wounds.[4] To further his claims, Koloman II forcibly married Michael's widow, the daughter of Rostislav, but he could not consolidate power and was killed almost immediately.[4] To protect his daughter, Rostislav now, early in 1257, invaded Bulgaria; it seems he was using her as an excuse to acquire the Bulgarian throne for himself.[4] Rostislav appeared at the gates of Tărnovo and recovered his daughter; though it is sometimes stated that he briefly obtained Tărnovo, but it seems that he probably never actually gained possession of the city.[4]

Having failed to take Tărnovo, Rostislav retreated to Vidin where he established himself, taking the title of Tsar of Bulgaria, and the Hungarians recognized him with this title.[4] Meanwhile, in southeastern Bulgaria, Mitso (a relative of Ivan Asen II) was proclaimed tsar, but the boyars who were holding Tărnovo elected one of their number, Constantine Tikh as tsar.[4]

Shortly afterwards, Rostislav led a large portion of his troops off to Bohemia in order to assist his father-in-law against King Ottokar II of Bohemia.[4] Thus his Vidin province became undermanned, and the situation was ideal for Tsar Constantine Tikh who attacked the token forces left behind in Vidin and regained not only the city but the whole province to the borders of the province of Braničevo.[4]

As soon as the Hungarians concluded peace with the Bohemians in March 1261, they, led by Stephen V of Hungary (co-king and Rostislav's brother-in-law) attacked Bulgaria.[4] They first overran the Vidin province and forced Tsar Constantine Tikh to withdraw his troops from it.[4] As a result of Hungary's action, Rostislav was restored to the position he had held prior to Constantine Tikh's attack on him in 1260.[4] Whether further Bulgarian territory east of Vidin (e.g., Lom) was taken by the Hungarians or Rostislav is not known.[4]

When he died, his lands were divided between two sons: his part of Bosnia went to his elder son Michael, while, Macsó went to his younger son, Béla; the immediate fate of Vidin is not known.[4]

Marriage and children

In 1243, Rostislav married Anna of Hungary (c. 1226 – after 1274), daughter of King Béla IV of Hungary and his wife, Maria Laskarina.[1] Together they had the following children:

- Duke Michael of Bosnia (? – 1271)[1]

- Duke Béla of Macsó (? – November, 1272)[1]

- Unnamed daughter (perhaps Anna), wife firstly of Tsar Michael Asen I of Bulgaria, secondly of Tsar Koloman II of Bulgaria[4]

- Kunigunda (1245 – September 9, 1285), wife firstly of King Ottokar II of Bohemia, and secondly of nobleman Záviš of Falkenštejn (Rosenberg)

- Agrippina (? – May 26, 1303/1309), wife of Prince Leszek II of Cracow

Ancestors

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kristó, Gyula; Engel, Pál; Makk, Ferenc. Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9-14. század).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 Dimnik, Martin. The Dynasty of Chernigov - 1146-1246.

- 1 2 Zsoldos, Attila. Családi ügy - IV. Béla és István ifjabb király viszálya az 1260-as években.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Fine, John V. A. (1987). The Late Medieval Balkans - A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. ISBN 9780472100798.

- ↑ Kristó, Gyula. Középkori históriák oklevelekben (1002-1410).

Sources

- Bárány, Attila (2020). "The Relations of King Emeric and Andrew II of Hungary with the Balkan States". Stefan the First-Crowned and His Time. Belgrade: Institute of History. pp. 213–249. ISBN 9788677431396.

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 9782825119587.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Dimnik, Martin: The Dynasty of Chernigov - 1146-1246; Cambridge University Press, 2003, Cambridge; ISBN 978-0-521-03981-9.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895-1526. London & New York: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781850439776.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Font, Márta (2020). "Rostislav, Dominus de Macho". Stefan the First-Crowned and His Time. Belgrade: Institute of History. pp. 309–326. ISBN 9788677431396.

- Isailović, Neven (2016). "Living by the Border: South Slavic Marcher Lords in the Late Medieval Balkans (13th–15th Centuries)". Banatica. 26 (2): 105–117.

- Jireček, Constantin (1911). Geschichte der Serben. Vol. 1. Gotha: Perthes.

- Kristó, Gyula: Középkori históriák oklevelekben (1002-1410) (Medieval Stories in Royal Charters /1002-1410/); Szegedi Középkorász Műhely in association with the Gondolat Kiadó, 1992, Szeged; ISBN 963-04-1956-4.

- Kristó, Gyula (General Editor) - Engel, Pál (Editor) - Makk, Ferenc (Editor): Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9-14. század) (Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History /9th-14th centuries/); Akadémiai Kiadó, 1994, Budapest; ISBN 963-05-6722-9.

- Voloshchuk, Myroslav (2020). "The Court of Rostyslav Mykhailovych, Prince and Dominus of Machou, in Hungary (An Excerpt from a Family History between the Late 13th and Mid 14th Centuries)". Journal of Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University. 7 (2): 42–50. doi:10.15330/jpnu.7.2.42-50. S2CID 234590260.

- Zsoldos, Attila: Családi ügy - IV. Béla és István ifjabb király viszálya az 1260-as években (A Family Affair - The Conflict of Béla IV and Junior King Stephen in the 1260s); História - MTA Történettudományi Intézete, 2007, Budapest; ISBN 978-963-9627-15-4.

- Харди, Ђура (2014). "О смрти господара Мачве кнеза Ростислава Михаилович". Наукові праці Кам'янець-Подільського національного університету імені Івана Огієнка: Історичні науки. Vol. 24. Кам’янець-Подільський. pp. 183–194.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)