| Part of a series about |

| Environmental economics |

|---|

|

The pollution haven hypothesis posits that, when large industrialized nations seek to set up factories or offices abroad, they will often look for the cheapest option in terms of resources and labor that offers the land and material access they require.[1] However, this often comes at the cost of environmentally unsound practices. Developing nations with cheap resources and labor tend to have less stringent environmental regulations, and conversely, nations with stricter environmental regulations become more expensive for companies as a result of the costs associated with meeting these standards. Thus, companies that choose to physically invest in foreign countries tend to (re)locate to the countries with the lowest environmental standards or weakest enforcement.

Three scales of the hypothesis

- Pollution control costs have an impact at the margins, where they exert some effect on investment decisions and trade flows.

- Pollution control costs are important enough to measurably influence trade and investment.

- Countries set their environmental standards below socially-efficient levels in order to attract investment or to promote their exports.[2]

Scales 1 and 2 have empirical support, but the significance of the hypothesis relative to other investment and trade factors is still controversial. One study found that environmental regulations have a strong negative effect on a country's FDI, particularly in pollution-intensive industries when measured by employment. However, that same study found that the environmental regulations present in a country's neighbors have an insignificant impact on that country's trade flows.[2]

Formula and variations

- Yi = αRi + XiβI + εi

In the above formula, Y is economic activity, R is regulatory stringency, X is an aggregate of other characteristics that affect Y and ε is an error term.[1] Theoretically, by changing your value of R, analysts will be able to calculate the expected effect on economic activity. According to the Pollution Haven Hypothesis, this equation shows that environmental regulations and economic activity are negatively correlated, because regulations raise the cost of key inputs to goods with pollution-intensive productions and reduce jurisdictions' comparative advantage in these goods. This lack of comparative advantage causes firms to move to countries with lower environmental standards, decreasing Y.

There is also an expanded formula, as shown below:

- Yit = vi + αRit + γTit + θRitTit + X’βit + εit

This expanded formula takes into account whether trade liberalization (i.e. the level of trade barriers that exist in a country, labeled as T) increases the negative correlation between economic activity (Y) and regulatory stringency (R). Some authors claim that trade barriers disproportionately effect the environment, and this equation attempts to quantify the interaction between trade barriers and regulatory stringency, and the corresponding effect with respect to output in an economy.[1]

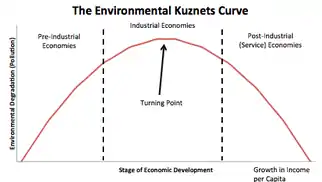

Connection with the environmental Kuznets curve

The environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) is a conceptual model that suggests that a country's pollution concentrations rise with development and industrialization up to a turning point, after which they fall again as the country uses its increased affluence to reduce pollution concentrations, suggesting that the cleaner environment in developed countries comes at the expense of a dirtier environment in developing countries.[3] In this sense, the EKC is potentially a reflection of the Pollution Haven Hypothesis, because one of the factors that may drive the increase in environmental degradation seen in pre-industrial economies is an influx of waste from post-industrial economies. This same transfer of polluting firms through trade and foreign investment could lead to the decrease in environmental degradation seen in downward-sloping section of the EKC, which models post-industrial (service) economies. This model holds true in cases of national development, but cannot necessarily be applied at a local scale.[4]

Real-world example

Spent batteries that Americans turn in to be recycled are increasingly being sent to Mexico, where the lead inside them is extracted by crude methods that are illegal in the United States. This increased export flow is a result of strict new Environmental Protection Agency standards on lead pollution, which make domestic recycling more difficult and expensive in the United States, but do not prohibit companies from exporting the work and danger to countries where environmental standards are low and enforcement is lax. In this sense, Mexico is becoming a pollution haven for the United States battery industry because Mexican environmental officials acknowledge that they lack the money, manpower, and technical capacity to police the flow. According to The New York Times in 2011, 20% of spent American vehicle and industrial batteries were being exported to Mexico, up from 6% in 2007, meaning that approximately 20 million batteries would cross the border that year. A significant proportion of this flow was being smuggled in after being mislabeled as metal scrap.[5]

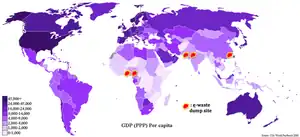

The world map shown here illustrates how e-waste dump sites (or sites where citizens or multinational corporations of industrialized nations dump their used electronic devices) along with the GDP PPP per-capita of those countries.[6]

While GDP PPP per-capita is not a perfect indicator of economic development, and e-waste dump sites are only one small facet of what could be a greater pollution haven, this map does illustrate how e-waste dump sites are often located in poorer, relatively pre-industrial nations, which provides some rudimentary support for the Pollution Haven Hypothesis.

Areas of controversy

The first area of controversy with respect to the Pollution Haven Theory has to do with the formulas above. Finding an appropriate measure of regulatory stringency (R) is not simple, because we want to know how much more costly production is in a given jurisdiction relative to others due to that jurisdiction's environmental regulations. The compliance costs stemming from these regulations, however, could come in the form of environmental taxes, regulatory delays, the threat or execution of lawsuits, product redesign, or emissions limits.[1] This proliferation of cost styles makes R hard to quantify.

Another major critique of the second formula is that it is difficult to measure regulatory stringency and trade barriers because the two effects are likely endogenous, so few studies have attempted to estimate the indirect effect of trade liberalization on pollution havens. Furthermore, governments at times engage in inefficient competition to actually attract polluting industries through weakening their environmental standards. However, as per conventional economic theory, welfare-maximizing governments should set standards so that the benefits justify the costs at the margin. This does not mean that environmental standards will be equal everywhere, as jurisdictions have different assimilative capacities, costs of abatement, and social attitudes regarding the environment, meaning heterogeneity in pollution standards is to be expected.[1] By extension, this means that industry migration to less stringent jurisdictions may not raise efficiency concerns in an economic sense.

A final area of controversy is whether the Pollution Haven Hypothesis has empirical support. For example, studies have found statistically significant evidence that countries with poor air quality do have higher net factor exports of coal, but the magnitude of the impact is small relative to other variables.[7] Paul Krugman, a Nobel Prize–winning economist, is skeptical as to whether pollution havens have empirical support in economic theory, as he writes, "At this point it's hard to come up with major examples of industries in which the pollution haven phenomenon, to the extent that it occurs, leads to international negative externalities. This does not, however, say that such examples cannot arise in the future."[8]

Scale 3 above has had empirical arguments made specifically against it, especially in the last 20 years. Some economists argue that once higher environmental standards are introduced in a country, larger multinational firms present in the country are likely to push for enforcement so as to reduce the cost advantage of smaller local firms. This effect would make countries with strict environmental standards a haven for the large companies often associated with higher levels of pollution, meaning the polluting agents may be smaller companies, rather than the larger MNCs as theorized by other proponents of the Pollution Haven Hypothesis.[9]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Levinson, Arik; M. Scott Taylor (2008). "Unmasking the Pollution Haven Effect" (PDF). International Economic Review. 49 (1): 223–54. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2354.2008.00478.x.

- 1 2 Millimet, Daniel. "Four New Empirical Tests of the Pollution Haven Hypothesis When Environmental Regulation is Endogenous" (PDF). Tulane University. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Ibara, Brian (January 2007). "Exploring the Causality between the Pollution Haven Hypothesis and the Environmental Kuznets Curve". Honors Projects. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ↑ Moseley, Perramond, Hapke, Laris, William G., Eric, Holly M., Paul (2014). An Introduction to Human-Environment Geography. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-1-4051-8932-3 – via Open edition.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Rosenthal, Elizabeth (8 December 2013). "Lead from Old US Batteries Sent to Mexico Raises Risks". New York Times. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ "Where does e-waste end up?". Greenpeace. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ Kellogg, Ryan (2006). The Pollution Haven Hypothesis: Significance and Insignificance. Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, UC Berkeley.

- ↑ Krugman, Paul (2006). International Economics Theory and Policy. Addison Wesley. ISBN 9780321451347.

- ↑ Birdsall, Nancy; Wheeler, David (January 1993). "Trade Policy and Industrial Pollution in Latin America: Where Are the Pollution Havens?". The Journal of Environment & Development. 2 (1): 137–149. doi:10.1177/107049659300200107. S2CID 154239425.