The piezoresistive effect is a change in the electrical resistivity of a semiconductor or metal when mechanical strain is applied. In contrast to the piezoelectric effect, the piezoresistive effect causes a change only in electrical resistance, not in electric potential.

History

The change of electrical resistance in metal devices due to an applied mechanical load was first discovered in 1856 by Lord Kelvin. With single crystal silicon becoming the material of choice for the design of analog and digital circuits, the large piezoresistive effect in silicon and germanium was first discovered in 1954 (Smith 1954).[1]

Mechanism

In conducting and semi-conducting materials, changes in inter-atomic spacing resulting from strain affect the bandgaps, making it easier (or harder depending on the material and strain) for electrons to be raised into the conduction band. This results in a change in resistivity of the material. Within a certain range of strain this relationship is linear, so that the piezoresistive coefficient

where

- ∂ρ = Change in resistivity

- ρ = Original resistivity

- ε = Strain

are constant.

Piezoresistivity in metals

Usually the resistance change in metals is mostly due to the change of geometry resulting from applied mechanical stress. However, even though the piezoresistive effect is small in those cases it is often not negligible. In cases where it is, it can be calculated using the simple resistance equation derived from Ohm's law;

where

- Conductor length [m]

- A Cross-sectional area of the current flow [m²][2]: p.207

Some metals display piezoresistivity that is much larger than the resistance change due to geometry. In platinum alloys, for instance, piezoresistivity is more than a factor of two larger, combining with the geometry effects to give a strain gauge sensitivity of up to more than three times as large than due to geometry effects alone. Pure nickel's piezoresistivity is -13 times larger, completely dwarfing and even reversing the sign of the geometry-induced resistance change.

Piezoresistive effect in bulk semiconductors

The piezoresistive effect of semiconductor materials can be several orders of magnitudes larger than the geometrical effect and is present in materials like germanium, polycrystalline silicon, amorphous silicon, silicon carbide, and single crystal silicon. Hence, semiconductor strain gauges with a very high coefficient of sensitivity can be built. For precision measurements they are more difficult to handle than metal strain gauges, because semiconductor strain gauges are generally sensitive to environmental conditions (especially temperature).

For silicon, gauge factors can be two orders of magnitudes larger than those observed in most metals (Smith 1954). The resistance of n-conducting silicon mainly changes due to a shift of the three different conducting valley pairs. The shifting causes a redistribution of the carriers between valleys with different mobilities. This results in varying mobilities dependent on the direction of current flow. A minor effect is due to the effective mass change related to changing shapes of the valleys. In p-conducting silicon the phenomena are more complex and also result in mass changes and hole transfer.

Giant piezoresistance in metal-silicon hybrid structures

A giant piezoresistive effect – where the piezoresistive coefficient exceeds the bulk value – was reported for a microfabricated silicon-aluminium hybrid structure.[3] The effect has been applied to silicon-based sensor technologies.[4]

Giant piezoresistive effect in silicon nanostructures

The longitudinal piezoresistive coefficient of top-down fabricated silicon nanowires was measured to be 60% larger than in bulk silicon.[5][6] In 2006, giant piezoresistance[7] was reported in bottom-up fabricated silicon nanowires – a >30 increase in the longitudinal piezoresistive coefficient compared to bulk silicon was reported. The suggestion of a giant piezoresistance in nanostructures has since stimulated much effort into a physical understanding of the effect not only in silicon [8][9][10][11][12][13][14] but also in other functional materials. [15]

Piezoresistive silicon devices

The piezoresistive effect of semiconductors has been used for sensor devices employing all kinds of semiconductor materials such as germanium, polycrystalline silicon, amorphous silicon, and single crystal silicon. Since silicon is today the material of choice for integrated digital and analog circuits the use of piezoresistive silicon devices has been of great interest. It enables the easy integration of stress sensors with Bipolar and CMOS circuits.

This has enabled a wide range of products using the piezoresistive effect. Many commercial devices such as pressure sensors and acceleration sensors employ the piezoresistive effect in silicon. But due to its magnitude the piezoresistive effect in silicon has also attracted the attention of research and development for all other devices using single crystal silicon. Semiconductor Hall sensors, for example, were capable of achieving their current precision only after employing methods which eliminate signal contributions due to applied mechanical stress.

Piezoresistors

Piezoresistors are resistors made from a piezoresistive material and are usually used for measurement of mechanical stress. They are the simplest form of piezoresistive devices.

Fabrication

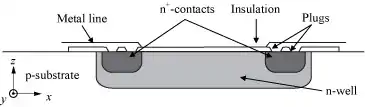

Piezoresistors can be fabricated using wide variety of piezoresistive materials. The simplest form of piezoresistive silicon sensors are diffused resistors. Piezoresistors consist of a simple two contact diffused n- or p-wells within a p- or n-substrate. As the typical square resistances of these devices are in the range of several hundred ohms, additional p+ or n+ plus diffusions are a potential method to facilitate ohmic contacts to the device.

Schematic cross-section of the basic elements of a silicon n-well piezoresistor.

Physics of operation

For typical stress values in the MPa range the stress dependent voltage drop along the resistor Vr, can be considered to be linear. A piezoresistor aligned with the x-axis as shown in the figure may be described by

where , I, , , and denote the stress free resistance, the applied current, the transverse and longitudinal piezoresistive coefficients, and the three tensile stress components, respectively. The piezoresistive coefficients vary significantly with the sensor orientation with respect to the crystallographic axes and with the doping profile. Despite the fairly large stress sensitivity of simple resistors, they are preferably used in more complex configurations eliminating certain cross sensitivities and drawbacks. Piezoresistors have the disadvantage of being highly sensitive to temperature changes while featuring comparatively small relative stress dependent signal amplitude changes.

Other piezoresistive devices

In silicon the piezoresistive effect is used in piezoresistors, transducers, piezo-FETS, solid state accelerometers and bipolar transistors.

The electrically-conductive packaging material Velostat is used by hobbyists to make pressure sensors due to is piezoresistive properties and low cost.

See also

References

- ↑ Barlian, A.A.; Park, W.-T.; Mallon, J.R.; Rastegar, A.J.; Pruitt, B.L. (March 2009). "Review: Semiconductor Piezoresistance for Microsystems". Proceedings of the IEEE. 97 (3): 513–552. doi:10.1109/jproc.2009.2013612. ISSN 0018-9219. PMC 2829857. PMID 20198118.

- ↑ Liu, Chang (2006). "Piezoresistive Sensors" (PDF). Foundations of MEMS. Upper Saddle River, NG: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0131472860. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ↑ Rowe, A. C. H.; Donoso-Barrera, A.; Renner, Ch.; Arscott, S. (April 8, 2008). "Giant Room-Temperature Piezoresistance in a Metal-Silicon Hybrid Structure". Physical Review Letters. 100 (14): 145501. arXiv:0803.0655. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.100n5501R. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.100.145501. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 18518044. S2CID 42265969.

- ↑ Ngo, H.-D.; Tekin, T.; Vu, T.-C.; Fritz, M.; Kurniawan, W.; Mukhopadhyay, B.; Kolitsch, A.; Schiffer, M.; Lang, K.-D. (2011). MEMS sensor with giant piezoresistive effect using metall-semiconductor hybrid structure. 16th International Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems Conference. IEEE. p. 1018-1021. doi:10.1109/transducers.2011.5969160.

- ↑ Toriyama, T.; Tanimoto, Y.; Sugiyama, S. (2002). "Single crystal silicon nano-wire piezoresistors for mechanical sensors". Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). 11 (5): 605–611. doi:10.1109/jmems.2002.802905. ISSN 1057-7157.

- ↑ Toriyama, T.; Sugiyama, S. (2003). "Single crystal silicon piezoresistive nano-wire bridge". Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. Elsevier BV. 108 (1–3): 244–249. doi:10.1016/s0924-4247(03)00269-3. ISSN 0924-4247.

- ↑ He, Rongrui; Yang, Peidong (2006). "Giant piezoresistance effect in silicon nanowires". Nature Nanotechnology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 1 (1): 42–46. Bibcode:2006NatNa...1...42H. doi:10.1038/nnano.2006.53. ISSN 1748-3387. PMID 18654140. S2CID 17694712.

- ↑ Allain, P. (November 8, 2012). Étude des propriétés électro-thermo-mécaniques de nanofils en silicium pour leur intégration dans les microsystèmes (Doctoral) (in French). Université Paris Sud. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ↑ Reck, K.; Richter, J.; Hansen, O.; Thomsen, E.V. (2008). Piezoresistive effect in top-down fabricated silicon nanowires. 2008 IEEE 21st International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems. IEEE. p. 7-17. doi:10.1109/memsys.2008.4443757. ISSN 1084-6999.

- ↑ Yang, Peidong (2008). "Chemistry and physics of silicon nanowire". Dalton Transactions. Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) (33): 4387–4391. doi:10.1039/b801440j. ISSN 1477-9226. PMID 18698439.

- ↑ Milne, J. S.; Rowe, A. C. H.; Arscott, S.; Renner, Ch. (November 23, 2010). "Giant Piezoresistance Effects in Silicon Nanowires and Microwires". Physical Review Letters. 105 (22): 226802. arXiv:1010.1633. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.105v6802M. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.105.226802. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 21231411. S2CID 12201580.

- ↑ Koumela, A; Mercier, D; Dupré, C; Jourdan, G; Marcoux, C; Ollier, E; Purcell, S T; Duraffourg, L (September 2, 2011). "Piezoresistance of top-down suspended Si nanowires". Nanotechnology. IOP Publishing. 22 (39): 395701. Bibcode:2011Nanot..22M5701K. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/22/39/395701. ISSN 0957-4484. PMID 21891838. S2CID 24747354.

- ↑ Rowe, A.C.H. (March 28, 2014). "Piezoresistance in silicon and its nanostructures". Journal of Materials Research. 29 (6): 731–744. arXiv:1309.6445. Bibcode:2014JMatR..29..731R. doi:10.1557/jmr.2014.52. ISSN 0884-2914. S2CID 119238891.

- ↑ McClarty, M. M.; Jegenyes, N.; Gaudet, M.; Toccafondi, C.; Ossikovski, R.; Vaurette, F.; Arscott, S.; Rowe, A. C. H. (July 11, 2016). "Geometric and chemical components of the giant piezoresistance in silicon nanowires". Applied Physics Letters. 109 (2): 023102. arXiv:1512.01396. Bibcode:2016ApPhL.109b3102M. doi:10.1063/1.4955403. ISSN 0003-6951. S2CID 119189299.

- ↑ Ali, Utku Emre; Modi, Gaurav; Agarwal, Ritesh; Bhaskaran, Harish (March 18, 2022). "Real-time nanomechanical property modulation as a framework for tunable NEMS". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 1464. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.1464A. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-29117-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8933423. PMID 35304454.

- Kanda, Yozo (1991). "Piezoresistance effect of silicon". Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. Elsevier BV. 28 (2): 83–91. doi:10.1016/0924-4247(91)85017-i. ISSN 0924-4247.

- S. Middelhoek and S. A. Audet, Silicon Sensors, Delft, The Netherlands: Delft University Press, 1994.

- A. L. Window, Strain Gauge Technology, 2nd ed, London, England: Elsevier Applied Science, 1992.

- Smith, Charles S. (April 1, 1954). "Piezoresistance Effect in Germanium and Silicon". Physical Review. American Physical Society (APS). 94 (1): 42–49. Bibcode:1954PhRv...94...42S. doi:10.1103/physrev.94.42. ISSN 0031-899X.

- S. M. Sze, Semiconductor Sensors, New York: Wiley, 1994.