| Pac-Man | |

|---|---|

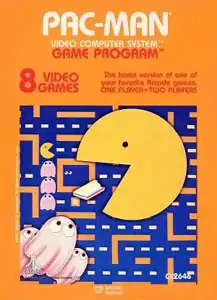

Atari 2600 cover art for Pac-Man | |

| Developer(s) | Atari, Inc. |

| Publisher(s) | Atari, Inc. |

| Designer(s) | Tod Frye |

| Series | Pac-Man |

| Platform(s) | Atari 2600 |

| Release | March 16, 1982[1][2][3] |

| Genre(s) | Maze |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, two-player |

Pac-Man is a 1982 maze video game developed and published by Atari, Inc. under official license by Namco, and an adaptation of the 1980 hit arcade game of the same name. The player controls the title character, who attempts to consume all of the wafers in a maze while avoiding four ghosts that pursue him. Eating flashing wafers at the corners of the screen causes the ghosts to temporarily turn blue and flee, allowing Pac-Man to eat them for bonus points. Once eaten, a ghost is reduced to a pair of eyes, which return to the center of the maze to be restored.

Programmed by Tod Frye, Pac-Man took six months to complete. Expecting high sales, Atari produced over a million copies of the highly anticipated game and held a "National Pac-Man Day" on April 3, 1982 to promote its release.[4]

It remains the best-selling Atari 2600 game of all time, selling over 8 million copies, and was the all time best-selling video game for several years. Despite its commercial success, Pac-Man was panned by critics for poor graphics and sound, and for bearing little resemblance to the original game. It has been considered one of the worst video games ever made and one of the worst arcade game ports released on the system.

Gameplay

The player uses a joystick to control Pac-Man, navigating him through a maze of consumable dashes called video wafers, opposed by a quartet of multi-colored ghosts.[5][6] The goal of the game is to earn a high score by having Pac-Man eat video wafers, power pills, vitamins and ghosts. Every time Pac-Man eats all the video wafers in the mze, he earns an extra life and a new maze full of wafers.[7] A group of ghosts roam the maze, trying to eat Pac-Man. If one touches Pac-Man, he loses a life.[6] The player is awarded a bonus life upon successful completion of a level.[7] Pac-Man can be played as a one-player game or a two-player game with the players alternating turns after Pac-Man is eaten by a ghost.[8]

Near the corners of the maze are four larger, flashing consumables known as Power Pills that turn the ghosts into a blue transparent colour Pac-Man with the temporary ability to eat the ghosts and earn points.[5] When a ghost is eaten, its disembodied eyes return to the big square chamber in the center of the maze to respawn.[6] The blue ghosts turn pink during the last moments of a Power Pill's effect, signaling that they are about to become dangerous again.[5] The final consumable items are the Vitamins, which appear periodically directly below the nest an award the player with further points.[5]

The game has eight variations, offering two different starting speeds for Pac-Man and four speeds for the ghosts.[9] Setting the console's A–B difficulty switches can also handicap one or both players. If the switch is set to A, position, the power pills' effects do not last as long.[10]

Pac-Man for the Atari 2600 has various changes from the original game.[11] Visual changes include the ghosts not having unique colors, and not looking in the direction they are moving in. Pac-Man now features eyes in the game and only facing side-to-side as he navigates the maze.[11][12][13][14] The game no longers features collectible items such as fruits or the key, which are now replaced by the and orange box called the vitamin.[15] The game also lacks the cut-scenes and sounds from the arcade version.[16]

The game has a different maze than the arcade game.[11] There are fewer video wafers, and are displayed as thin rectangles instead of dots like in the arcade version.[17] The maze in this version of the game is simplified in structure and appearance, lacking the rounded edges lacking the more intricate passages of the arcade and changes the escape passages from the sides to the top and bottom of the screen.[6][13][18]

Development

After Pac-Man proved to be a success in the United States, Atari decided to license the game and produce it for its Atari 2600 console.[19][20]

Programming was assigned to Tod Frye, who was not provided with any arcade design specifications to work from and had to figure out how the game worked by playing it. He spent 80-hour weeks over six months developing it.[21] The finished game uses a 4 KB ROM cartridge, chosen for its lower manufacturing costs compared to 8 KB bank-switched cartridges which had recently become available.[19][20] As with any contemporary arcade port, the simple Atari 2600 hardware was a considerable limitation. The arcade PAC-MAN system board contained 2 KB of main RAM (random-access memory) in which to run the program, 2 KB of video RAM to store the screen state, and 16 KB of ROM (read-only memory) to store the game code, whereas the Atari 2600 featured only 128 bytes of RAM memory and none dedicated to video: effectively 32 times less RAM.[20] The Zilog Z80 CPU microprocessor used by the Namco Pac-Man arcade system is clocked at three times the speed of the MOS 6507 CPU in the Atari 2600 - though the Z80 typically does less work per clock cycle.[22]

To deal with these limitations, Frye simplified the maze's intricate pattern of corridors to a more repetitive pattern. The small tan pellets in the arcade original were changed to rectangular "wafers" that shared the wall color on 2600; a change necessitated because both the pellets and walls were drawn with the 2600's Playfield graphics, which have a fixed width. To achieve the visual effect of wafers disappearing as Pac-Man eats them, the actual map of the maze was updated as the data was written into the Playfield registers, excluding those pellets that had been eaten. The 2600's Player-Missile graphics system (sprites) was used for the remaining objects; the one-bit-wide Missiles were used to render the flashing power pills and the center of the vitamin. Pac-Man and ghost characters were implemented using the 2600's two Player objects, with one being used for Pac-Man and the other being used for all four ghosts, with the result that each ghost only appears once out of every four frames, which creates a flickering effect. This effect takes advantage of the slow phosphorescent fade of CRT monitors and the concept of persistence of vision, resulting in the image appearing to linger on screen longer,[20] but the flickering remains noticeable, and makes each individual ghost's color nearly impossible to discern.[23] Frye chose to abandon plans for a flicker-management system to minimize the flashing in part because Atari didn't seem to care about that issue in its zeal to have the game released. According to Frye, his game also did not conform to the arcade game's color scheme in order to comply with Atari's official home product policy that only space-type games should feature black backgrounds. Another quality impact was his decision that two-player gameplay was important, which meant that the 23 bytes required to store the current difficulty, state of the dots on the current maze, remaining lives, and the score had to be doubled for a second player,[24] consuming 46 of the 2600's meager 128-byte memory, which precluded its use for additional game data and features.[25]

Oft-repeated stories claim that the company wanted to or did release a prototype in order to capitalize on the 1981 holiday season;[20] however, the retail release was a final product. Frye states that there were no negative comments within Atari about these elements, but, after seeing the game, Coin Division marketing manager Frank Ballouz reportedly informed Ray Kassar, Atari's president and CEO, that he felt enthusiasts would not want to play it. His opinion, however, was dismissed.[19] The company ran newspaper ads and promoted the product in catalogs, describing it as differing "slightly from the original".[2]

To help sales, Atari promoted and protected its exclusive licensing of Pac-Man.[2][26] It took legal action against companies that released clones similar to Pac-Man.[26] Atari sued Philips for its 1981 Magnavox Odyssey² game K.C. Munchkin! alleging copyright infringement. In the landmark case Atari, Inc. v. North American Philips Consumer Electronics Corp., the Court of Appeals allowed a preliminary injunction against Philips to prevent the sale of Munchkin cartridges.[27][28] However, Atari failed to stop other games, such as On-Line Systems' Jawbreaker and Gobbler.[29]

Several retailers assisted Atari with the release of the game. JCPenney was the first retailer to launch a nationwide advertising campaign on television for a software title.[30] Continuing a long-standing relationship between it and Sears,[31] Atari also produced Pac-Man cartridges under the department store's label.[32]

Reception

Sales

Anticipation for the game was high.[2][30] Atari stated in 1981 that it had preorders for "three or four million" copies of the Atari 2600 version.[29] Goldman Sachs analyst Richard Simon predicted the sale of 9 million units during 1982, which would yield a profit of $200 million.[1] Pac-Man met with initial commercial success; more than one million cartridges had been shipped in less than one month, helped by Atari's $1.5 million publicity campaign.[33] It was the best-selling home video game of 1982,[34] with over 7.2 million cartridges sold that year[35] and over $200 million ($610 million adjusted for inflation) in gross revenue.[36] It replaced Space Invaders as the best-selling Atari 2600 title and also became the overall best-selling video game up until then (a title it held for several years until eventually being surpassed by Super Mario Bros).[35][37] Pac-Man also propelled Atari VCS sales to 12 million units by 1982.[38] Frye reportedly received $0.10 in royalties per copy.[39]

Purchases had slowed by the summer of 1982, with unsold copies available in large quantities.[2][19] Atari went on to sell over 684,000 cartridges in 1983.[35] It had sold a cumulative 7,956,413 cartridges by 1983,[35] and a further 139,173 units for $706,967 (equivalent to $1,800,000 in 2022) between 1986 and 1990,[40] for a total of over 8 million cartridges sold by 1990. By 2004, the cartridges were still very common among collectors and enthusiasts—though the Sears versions were rarer—and priced lower.[32]

Critical response

At release, critics negatively compared the port to its original arcade form, panning the audio-visuals and gameplay. On May 11, 1982, Electronic Games Magazine published its first bad review ever for an Atari video game, saying, "Considering the anticipation and considerable time the Atari designers had to work on it, it’s astonishing to see a home version of a classic arcade contest so devoid of what gave the original its charm". Video Magazine admitted it was "challenging, and there are a few visual pluses", before lamenting, "Unfortunately those who cannot evaluate Pac-Man through lover's eyes are likely to be disappointed". The premiere issue of Video Games Player from Fall 1982 called Pac-Man "just awful".[41] Electronic Games gave the game a rating of four out of ten.[42] Video Games Player magazine gave the graphics and sound its lowest rating of C, while giving the game an overall B− rating.[43] Electronic Fun with Computers & Games gave it an overall B− rating, with a C rating for graphics.[44]

In 1983, Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games reviewer Danny Goodman commented that the game fails as a replica of its arcade form: "Atari stated clearly in its description of the cartridge that Atari's Pac-Man 'differs slightly from the original'. That, perhaps, was an understatement." Conversely, he stated that such criticism was unfair because the hardware could not properly emulate the arcade game. Goodman further said that the port is a challenging maze game in its own right, and it would have been a success if fans had not expected to play a game closer to the original.[2] That year Phil Wiswell of Video Games criticized the game's poor graphics, mockingly referring to it as "Flickerman",[45] while Softline questioned why Atari opposed Pac-Man clones when the 2600 version was less like the original "than any of the pack of imitators".[46]

The game has remained poorly rated. Computer and Video Games magazine rated the game 57% in 1989.[47] Next Generation magazine editors in 1998 called it the "worst coin-op conversion of all time", and attributed the mass dissatisfaction to its poor quality.[19] In 2006, IGN's Craig Harris echoed similar statements and listed it as the worst arcade conversion, citing poor audio-visuals that did not resemble the original.[48] Another IGN editor, Levi Buchanan, described it as a "disastrous port", citing the color scheme and flickering ghosts.[49] Skyler Miller of AllGame said that although the game was only a passing resemblance to the original, it was charming despite its many differences and faults.[13]

Frye did not express regret over his part in Pac-Man's port and felt he made the best decisions he could at the time. However, Frye stated that he would have done things differently with a larger capacity ROM.[19] Video game industry researchers Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost attribute the poor reception to the technical differences between the 1977 Atari 2600 console and the 1980 arcade hardware used in Pac-Man cabinets. They further stated that the conversion is a lesson in maintaining the social and cultural context of the original source. Montfort and Bogost commented that players were disappointed with the flickering visual effect, which made the ghosts difficult to track and tired the players' eyes. The two further said that the effect diminishes the ghosts' personalities present in the arcade version.[20] Chris Kohler of Wired commented that the game was poorly received upon its release and in contemporary times because of the poor quality. However, he further described the game as an impressive technical achievement given its console's limitations.[50]

Impact and legacy

Initially, the excitement generated by Pac-Man's home release prompted retail stores to expand their inventory to sell video games. Drugstores began stocking video game cartridges, and toy retailers vied for new releases. Kmart and J. C. Penney competed against Sears to become the largest vendor of video games.[30] The game's release also led to an increase in sales of the Atari 2600 console.[51]

In retrospect, however, critics often cite Atari's Pac-Man as a major factor in the drop of consumer confidence in the company, which contributed to the video game crash of 1983. Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton of Gamasutra stated that the game's poor quality damaged the company's reputation.[26] Buchanan commented that it disappointed millions of fans and diminished confidence in Atari's games.[49][52] Former Next Generation editor-in-chief Neil West attributes his longtime skepticism of Atari's quality to the disappointment he had from buying the game as a child.[19] Calling the game the top video game disaster, Buchanan credits Pac-Man as a factor to the downfall of Atari and the industry in the 1980s.[52] Author Steven Kent also blames the game, along with Atari's E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, for severely damaging the company's reputation and profitability.[53] Montfort and Bogost stated that the game's negative reception seeded mistrust in retailers, which was reinforced by later factors that culminated in the crash.[20]

On December 7, 1982, Atari owner Warner Communications announced that revenue forecasts for 1982 were cut from a 50 percent increase over 1981 to a 15 percent increase.[19][54] Immediately following the announcement, the company's stock value dropped by around 35 percent—from $54 to $35—amounting to a loss of $1.3 billion in the company's market valuation.[19][55] Warner admitted that Pac-Man's good sales despite poor quality made Atari overconfident about E.T. and Raiders of the Lost Ark, which did not sell well.[56] In 1983, the company decreased its workforce by 30 percent and lost $356 million.[53]

In late 1982, Atari ported Pac-Man to its new console, the Atari 5200. This version was a more accurate conversion of the original arcade game and was a launch title for the console, along with eleven other games.[53][57]

The port was followed by conversions of Pac-Man's arcade sequels, Ms. Pac-Man and Jr. Pac-Man, for the Atari 2600. These used 8 KB ROM cartridges instead of Pac-Man's 4 KB and dispensed with two-player games. They were better received than Atari's first Pac-Man title[26] and addressed many critics' complaints of Pac-Man.[20]

References

- 1 2 Staff (1982-04-05). "Pac-Man Fever". Time. Time Inc. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Goodman, Danny (Spring 1983). "Pac-Mania". Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games. Vol. 1, no. 1. p. 122. Archived from the original on December 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Pac-Man gobbled up by video buffs". The Capital Times. Madison, Wisconsin. March 18, 1982.

Each of the three local Copps stores received 96 of the cartridges this week. They went on sale Tuesday morning, heralded by ads in the local newspapers.

- ↑ "Only Four More Days Until Atari National Pac-Man Day". March 30, 1982. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- 1 2 3 4 Pac-Man Atari Game Program Instructions. Atari. 1981. p. 2. C016943-46 REV 1.

- 1 2 3 4 Pac-Man Atari Game Program Instructions. Atari. 1981. pp. 3–4. C016943-46 REV 1.

- 1 2 Pac-Man Atari Game Program Instructions. Atari. 1981. p. 1. C016943-46 REV 1.

- ↑ Pac-Man Atari Game Program Instructions. Atari. 1981. p. 7. C016943-46 REV 1.

- ↑ Pac-Man Atari Game Program Instructions. Atari. 1981. p. 8. C016943-46 REV 1.

- ↑ Pac-Man Atari Game Program Instructions. Atari. 1981. p. 6. C016943-46 REV 1.

- 1 2 3 Weiss, Brett (2014). The 100 Greatest Console Video Games 1977-1987. Schiffer Publishing. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-7643-4618-7.

- ↑ Montfort, Nick; Bogost, Ian (2009). "Pac-Man". Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. MIT Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- 1 2 3 Miller, Skyler. "Pac-Man - Overview". AllGame. Archived from the original on February 14, 2010. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ↑ Montfort, Nick; Bogost, Ian (2009). "Pac-Man". Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. MIT Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- ↑ Montfort, Nick; Bogost, Ian (2009). "Pac-Man". Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. MIT Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- ↑ Montfort, Nick; Bogost, Ian (2009). "Pac-Man". Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. MIT Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- ↑ Montfort, Nick; Bogost, Ian (2009). "Pac-Man". Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. MIT Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- ↑ Montfort, Nick; Bogost, Ian (2009). "Pac-Man". Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. MIT Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Staff (April 1998). "What the hell happened?". Next Generation Magazine. No. 40. Imagine Media. p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Montfort, Nick; Bogost, Ian (2009). "Pac-Man". Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. MIT Press. pp. 66–79. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- ↑ Lapetino, Tim (2018). "The Story of PAC-MAN on Atari 2600". Retro Gamer Magazine. 179: 18–23.

- ↑ Montfort, Nick; Bogost, Ian (2009). Racing the beam: the Atari Video computer system. MIT Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ↑ Bogost, Ian; Montfort, Nick (2009). Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. The MIT Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- ↑ "In defense of Pac-Man... - Page 6 - Atari 2600". AtariAge Forums. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ↑ Reutter, Hans (October 27, 2016). PRGE 2016 - Tod Frye - Portland Retro Gaming Expo. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved May 12, 2017 – via YouTube.

- 1 2 3 4 Barton, Matt; Loguidice, Bill (February 28, 2008). "A History of Gaming Platforms: Atari 2600 Video Computer System/VCS". Gamasutra. p. 5. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ↑ Graham, Lawrence D. (1999). "Video Game Wars". Legal Battles that Shaped the Computer Industry. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 27–30. ISBN 978-0-585-39311-7.

- ↑ Loguidice, Bill; Barton, Matt (2009). "Pac-Man (1980): Japanese Gumption, American Consumption". Vintage Games: An Insider Look at the History of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the Most Influential Games of All Time. Focal Press. pp. 185–186. ISBN 978-0-240-81146-8.

- 1 2 Tommervik, Allan (January 1982). "The Great Arcade/Computer Controversy / Part 1: The Publishers and the Pirates". Softline. p. 18. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 Kent, Steven (2001). "The Fall". The Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7.

- ↑ Fulton, Steve (August 21, 2008). "Atari: The Golden Years -- A History, 1978-1981". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- 1 2 Ellis, David (2004). "The Atari VCS (2000)". Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-375-72038-3.

- ↑ Corderi, Victoria (March 30, 1982). "Local Video-game Freaks Gobble Up Home Pac-Man". The Miami News. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- ↑ "Apathy crushes video game industry". Army Host. Club Management Directorate, The Adjutant General Center. 10 (4): 6. 1983.

Almost 7 million Pac-Man game cartridges were sold last year

- 1 2 3 4 Cartridge Sales Since 1980. Atari Corp. Via "The Agony & The Ecstasy". Once Upon Atari. Episode 4. Scott West Productions. August 10, 2003. 23 minutes in.

- ↑ Green, Mark J.; Berry, John Francis (1985). The Challenge of Hidden Profits: Reducing Corporate Bureaucracy and Waste. W. Morrow. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-688-03986-8.

By 1981, Atari's sales grew to $1 billion as it controlled about 75 percent of the fast-growing video game market. The dizzying climb continued into 1982, with Pac-Man alone bringing in over $200 million.

- ↑ Katz, Arnie; Kunkel, Bill (May 1982). "The A-Maze-ing World of Gobble Games" (PDF). Electronic Games. 1 (3): 62–63 [63]. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ↑ Hubner, John; Kistner, William F. (28 November 1983). "The Industry: What went wrong at Atari?". InfoWorld. Vol. 5, no. 48. InfoWorld Media Group, Inc. pp. 151–158 (157). ISSN 0199-6649.

- ↑ "Designer Profile: Chris Crawford (Part 2)" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. Jan–Feb 1987. pp. 56–59. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 14, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ↑ Vendel, Curt (May 28, 2009). "Site News". Atari Museum. Archived from the original on 2010-12-06. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ↑ "Fall 1982 Complete Home Video Games Buyer's Guide". Video Games Player. Vol. 1, no. 1. Illustrated by Kris Boyd. Carnegie Publications. September 1982. p. 59. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "Pac-Man: Atari VCS". Electronic Games (1983 Software Encyclopedia): 28. 1983.

- ↑ "Software Report Card". Video Games Player. Vol. 1, no. 1. United States: Carnegie Publications. September 1982. pp. 62–3.

- ↑ "Video Game Explosion! We rate every game in the world". Electronic Fun with Computers & Games. Vol. 1, no. 2. December 1982. pp. 12–7.

- ↑ Wiswell, Phil (March 1983). "New Games From Well-Known Names". Video Games. 1 (6): 71. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Strange Games" (PDF). Softline. March 1983. p. 49. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Complete Games Guide" (PDF). Computer and Video Games (Complete Guide to Consoles): 46–77. 16 October 1989.

- ↑ Harris, Craig (June 27, 2006). "Top 10 Tuesday: Worst Coin-op Conversions". IGN. Archived from the original on November 14, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- 1 2 Buchanan, Levi (August 26, 2008). "Top 10 Best-Selling Atari 2600 Games". IGN. Archived from the original on October 24, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ↑ Kohler, Chris (March 13, 2009). "Racing the Beam: How Atari 2600's Crazy Hardware Changed Game Design". Wired. Archived from the original on September 10, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

- ↑ Hubner, John; Kistner, William F. Jr. (November 28, 1983). "What went wrong at Atari?". InfoWorld. Vol. 5, no. 48. InfoWorld Media Group, Inc. p. 157. ISSN 0199-6649.

- 1 2 Buchanan, Levi (November 26, 2008). "Top 10 Videogame Turkeys". IGN. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Kent, Steven (2001). "The Fall". The Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 237–239. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7.

- ↑ Staff (December 2004). "This Month in Gaming History". Game Informer. No. 140. GameStop. p. 202.

- ↑ Taylor, Alexander L. (December 20, 1982). "Pac-Man Finally Meets His Match". Time. Vol. 120, no. 25. Retrieved September 30, 2009.

- ↑ Pollack, Andrew (1982-12-19). "THE GAME TURNS SERIOUS AT ATARI (Published 1982)". The New York Times. p. Section 3, Page 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ↑ Kent, Steven (2001). "The Fall". The Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7.