State of New York | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) Flag |

.svg.png.webp) |

|

Union states in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

|

| Dual governments |

| Territories and D.C. |

The state of New York during the American Civil War was a major influence in national politics, the Union war effort, and the media coverage of the war. New York was the most populous state in the Union during the Civil War, and provided more troops to the U.S. army than any other state, as well as several significant military commanders and leaders.[1] New York sent 400,000 men to the armed forces during the war. 22,000 soldiers died from combat wounds; 30,000 died from disease or accidents; 36 were executed.[2] The state government spent $38 million on the war effort; counties, cities and towns spent another $111 million, especially for recruiting bonuses.[3]

The voters were sharply divided politically. A significant anti-war movement emerged, particularly in the mid- to late-war years. The Democrats were divided between War Democrats who supported the war and Copperheads who wanted an early peace. Republicans divided between moderates who supported Lincoln, and Radical Republicans who demanded harsh treatment of the rebel states. New York provided William H. Seward as Lincoln's Secretary of State, as well as several important voices in Congress.

The press, largely based in New York City, helped shape and mold state and national opinion. The New York Tribune influenced Republican editorials across the country. Influential magazines included Harper's Weekly and Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. Thomas Nast was among the early political cartoonists.[4]

In the decades after the war ended, numerous memorials and monuments were erected across the Empire State to commemorate specific regiments, units, and officers associated with the war effort. Several archives and repositories, as well as historical societies, hold archives and collections of relics and artifacts.

Military recruitment

Upstate New York was among the leaders in the revolutions in transportation, agriculture, and industry. Turnpikes, canals (notably the Erie Canal), and railroads connected eastern cities with western markets. New York's farmland was some of the most productive in the nation. The Genesee country became known as the breadbasket of the nation for its extraordinary grain production. Rapid-flowing rivers offered power for major industrial sites. Following these expanding economic opportunities, people (including African Americans as well as European Americans of many different backgrounds) poured into upstate New York. They came from several different cultures—New England Yankees, Dutch and Yorkers from eastern New York, Germans and Scots Irish from Pennsylvania, and immigrants from England and Ireland.[5]

New York provided 400,000–460,000 men during the war, nearly 21% of all the men in the state and more than half of those under the age of 30. Of the total enlistment, more than 130,000 were foreign-born, including 20,000 from British North American possessions such as Canada. 51,000 were Irish and 37,000 German. The average age of the New York soldiers was 25 years, 7 months, although many younger men and boys may have lied about their age in order to enlist.[6]

By the time the Civil War ended in 1865, New York had provided the Union Army with 27 regiments of cavalry, 15 regiments of artillery, 8 of engineers, and 248 of infantry.[7] Federal records indicate 4,125 free blacks from New York served in the Union Army, and three full regiments of United States Colored Troops were raised and organized in the Empire State—the 20th, 26th, and 31st USCT.[8]

Among the more prominent military units from the state of New York was the Excelsior Brigade of controversial former congressman Daniel Sickles.[9] Francis B. Spinola was commissioner of New York Harbor when the war erupted; he joined the volunteer army in a New York regiment and was commissioned as an officer, appointed brigadier general of Volunteers, and recruited and organized a brigade of four regiments, known as Spinola's Empire Brigade.[10] Several early volunteer regiments traced their origins to antebellum New York State Militia regiments, including the 14th Brooklyn, which became known for its bright red chasseur-style pants.[11]

The first organized unit to leave the state for the front lines was the 7th New York State Militia, which departed by train for Washington, D.C., on April 19, 1861. The 11th New York Infantry, a two-years' regiment of new recruits, departed ten days later.[12] Among the earliest casualties of the Civil War was Malta, New York, native Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth, who was killed in May 1861 during an armed encounter in Alexandria, Virginia.[13]

Supporting the war effort

New York had long played an important role in the U.S. military, with the United States Military Academy in West Point providing a significant number of officers to the antebellum Regular Army. New York Harbor was ringed with several military outposts, forts, and garrisons, and many officers who were prominent during the war had spent considerable time in New York before the conflict erupted in early 1861. McDougall Hospital at Fort Schuyler would become a leading wartime military hospital,[14] and Davids Island was a significant prisoner-of-war camp for captured Confederates.

Several wealthy New York industrialists played crucial roles in supporting the war effort through materiel, weapons, ammunition, supplies, and accoutrements. Railroad impresario Cornelius Vanderbilt used his growing network of rail systems to effectively move large quantities of troops through the state to staging and training areas.[15] The Union Navy contracted with U.S. Congressman Erastus Corning's iron works to manufacture parts and materials for the USS Monitor, the Navy's first ironclad warship. The Brooklyn Navy Yard was an important shipbuilding and naval maintenance concern.[16]

Foundrymen Robert Parrott and his brother Peter produced significant quantities of artillery pieces and munitions, and their Parrott rifle, an innovative rifled gun, was manufactured in several sizes at the West Point Foundry.[17] The National Arms Company in Brooklyn produced firearms, including large quantities of revolvers. Other important producers of weaponry and munitions were the Federal government's Watervliet Arsenal[18] and the privately owned Remington Arms Company of Ilion.[19]

Wartime politics

In the presidential election of 1860, 362,646 (53.7%) New York voters chose Abraham Lincoln, with 312,510 (46.3%) supporting Democrat Stephen Douglas.[20]

Powerful New York politicians played important roles in setting national policy and procedures during the war. Roscoe Conkling was among the leading Radical Republicans who strongly supported the vigorous prosecution of the war. They were opposed by moderate Republicans including Henry Jarvis Raymond, a New York newspaperman who served as the Chairman of the Republican National Committee in the latter half of the war. William H. Seward, a United States Senator from New York and an outspoken critic of Lincoln, became the Secretary of State and an important member of Lincoln's Cabinet.[21]

By contrast, the colorful mayor of New York City, Fernando Wood, was a prominent early supporter of the Confederate cause. He argued unsuccessfully that the city should secede from the Union as a separate entity.[22] New York City had many economic and financial ties to the South; by 1820, half of its exports were related to cotton, and upstate textile mills processed Southern cotton. In addition, the numerous immigrants in New York worried that freeing slaves would bring more labor competition to a market where they struggled over the lowest-paid jobs.

When the war began, former New York Governor Horatio Seymour took a cautious middle position within his Democratic Party, supporting the war effort but criticizing its conduct by the Lincoln administration. Seymour was especially critical of Lincoln's wartime centralization of power and restrictions on civil liberties, as well as his support of emancipation. In 1862, Seymour was again elected governor, defeating Republican candidate James S. Wadsworth. As governor of the Union's largest state, Seymour was the most prominent Democratic opponent of the President for the next two years. He strongly opposed the Lincoln administration's institution of the military draft in 1863.[23]

Alfred Ely, Chairman of the House Committee on Invalid Pensions, was among the first U.S. representatives to be captured by the Confederate Army when he and other civilian onlookers were taken prisoner following the First Battle of Bull Run. He spent six months in a Confederate prison before being exchanged and released.[24]

In 1861 and 1862, former U.S. Senator Hamilton Fish became associated with John A. Dix, William M. Evarts, William E. Dodge, A.T. Stewart, John Jacob Astor, and other New York men on the Union Defence Committee. They cooperated with the New York City government in raising and equipping troops, and disbursed more than $1 million for the relief of New York volunteers and their families. Later in the war, several leading New York politicians and businessmen helped found the Union League, a pro-Union, pro-Lincoln organization that helped fund the Republican Party, as well as charitable relief groups such as the United States Sanitary Commission.[25]

During the Gettysburg Campaign of 1863, despite his sharp political differences with Pennsylvania's Republican Governor Andrew G. Curtin, Governor Seymour dispatched significant quantities of New York State Militia to Harrisburg to help repel the invasion of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.[26] The first Union soldier killed on Pennsylvania soil was a native Pennsylvanian, Corporal William H. Rihl serving in a company assigned to the 1st New York Cavalry.[27][28]

Lingering effects of the New York Draft Riots

During the draft riots of July 1863, 120 civilians were killed and 2,000 men injured. The draft riots also resulted in about $1,000,000 in property damage. This was also coupled with a strong anti-war movement sparked by Copperheads and other Peace Democrats, made New York one of the closest contested states in the presidential election of 1864. 368,735 (50.46%) New Yorkers chose the incumbent Abraham Lincoln, with 361,986 (49.54%) supporting Democratic challenger and former army commander George B. McClellan. Lincoln captured all 33 electoral votes.[20]

The New York Legislature oversaw the approval of funding the state's war effort, including bounties, fees, expenses, interest on loans, and for the support of the families of soldiers where needed. Total expenditures exceeded $152 million during the war.[29]

Military actions

No Civil War battles were fought within the Empire State, although Confederate agents did set several fires in New York City as an act intended to terrorize the community and build support for the peace movement.[30]

New York troops were prominent in virtually every major battle in the Eastern Theater, and some New York units participated in leading campaigns in the Western Theater, albeit in significantly smaller numbers than in the East. New Yorker John Schofield rose to command of the Army of the Ohio and won the Battle of Franklin, dealing a serious blow to Confederate hopes in Tennessee.

More than 27,000 New Yorkers fought in the war's bloodiest battle, the three-day Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. Nearly 1,000 men - 989 soldiers were killed in action, with 4,023 wounded (many of whom died of wounds or disease in the months following the battle). 1,761 New Yorkers were taken as prisoners of war, and many were transported to Southern prisons in Richmond, Virginia and elsewhere. It was the largest number of casualties for New York troops in any battle.[31]

Among the scores of officers from New York to die at Gettysburg was Brig. Gen. Samuel K. Zook, a long-time resident of New York City.[32] Col. Patrick "Paddy" O'Rourke of Rochester died a hero while leading the 140th New York Infantry into action on Little Round Top.[33] Col. Augustus van Horne Ellis was killed near Devil's Den on July 2; he was later memorialized with the only full-sized statue of a regimental commander to be erected on the battlefield.[34]

During the entire war, New York provided more than 370,000 soldiers to the Union armies. Of these, 834 officers were killed in action, as well as 12,142 enlisted men. Another 7,235 officers and men perished from their wounds, and 27,855 died from disease. Another 5,766 were estimated to have perished while incarcerated in Southern prisoner-of-war camps.[1]

New York City

New York City, the most populous in the United States, was a bustling city that provided a major source of troops, supplies, and equipment for the Union Army. Powerful city politicians and newspaper editors helped shape public opinion towards the war effort and the policies of President Lincoln. The port of New York served as fertile recruiting grounds for the Army as immigrants from Europe (primarily Irish and Germans) at times stepped off the oceanic transports and into the muster rolls. Recruiters such as Michael Corcoran filled muster rolls with thousands of immigrants in response to Lincoln's initial call for 75,000 volunteers from New York.[35]

Politically, the city was dominated by Democrats, many of whom were under the control of a political machine known as Tammany Hall. Led by William "Boss" Tweed, they gained numerous offices in New York City, and even to the state legislature and judges' seats, often through illegal means. From 1860 to 1870, Tweed controlled most Democratic nominations in the city, while Republicans tended to be more prevalent in upstate New York.[36]

Draft Riots

The city's growing Irish and German immigrant population, and anger about conscription led to the Draft Riots of 1863, one of the worst incidents of civil unrest in American history.[37] The week of July 11 to July 16, 1863, was known at the time as "Draft Week".[38] Residents, mainly Irish immigrants, were upset with new laws passed by Congress to draft men to fight on what they viewed was the unpopular Civil War. The ensuing disturbances were the largest civil insurrection in American history apart from the Civil War.[39] President Lincoln sent several regiments of militia and federal troops to control the city. Irish rioters numbered in the thousands and began rampaging through the streets of New York, attacking blacks and burning whatever building that either belonged to the wealthy or was sympathetic to the Union cause.[40] Smaller-scale riots erupted in other cities throughout the North, including in other places in New York State, at about the same time.[41]

The exact death toll during the New York Draft Riots is unknown, but according to historian James M. McPherson (2001), at least 120 civilians were killed.[42] Estimates are that at least 2,000 more were injured. Total property damage was about $1 million.[43] Historian Samuel Morison wrote that the riots were "equivalent to a Confederate victory".[43] The city treasury later indemnified one-quarter of the amount. Fifty buildings, including two Protestant churches, burned to the ground. On August 19, the draft was resumed.

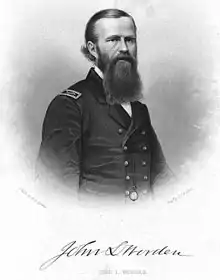

Notable leaders from New York

New York was the most populous state in the Union at the outbreak of the American Civil War, with more than 3.5 million residents.[44] As such, it provided a significant number of leading generals, admirals, and politicians who were either born in New York or spent considerable time there before the war. A few of New York's most noted native sons follow, with their birthplaces in parentheses:[45]

Other notable New Yorkers during the Civil War include Union spy and conductor of the Underground Railroad Harriet Tubman, war photographer Mathew Brady, English-born artist Alfred Waud, newspaperman Horace Greeley, and combat artist Edwin Forbes.[46]

James Wadsworth, one of the wealthiest men in the state and a former Republican candidate for governor, was among the Union generals from New York to be killed during the war. Others included George D. Bayard of Seneca Falls, Daniel D. Bidwell of Buffalo, David A. Russell of Salem, Stephen H. Weed of Potsdam, and Thomas Williams of Albany.[46]

Memorialization

The Grand Army of the Republic and other veterans organizations throughout New York contributed to the erection of hundreds of individual statues, fountains, busts, and other commemorations, as well as building several meeting halls where they could relive war events and keep their relics and artifacts relatively safe.[47]

Women played an important role on New York's home front during the role, providing support, encouragement, and material goods to the soldiers, as well as helping with the United States Sanitary Commission and United States Christian Commission. Several New York ladies served as nurses to ill and wounded soldiers at a variety of military hospitals throughout the state. On April 24, 1886, the state legislature authorized the New York chapter of the GAR to erect a large memorial on the grounds of the Capitol in Albany in honor of the women of the state for their "humane and patriotic acts during the war."[48]

Among the more impressive Civil War-related monuments and memorials in the state is the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch in Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn, which depicts equestrian relief bronzes of Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant.[49] Grant, the commander of the Union armies during the latter half of the war, is buried in New York City in Grant's Tomb.[50] The Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument, located at 89th Street and Riverside Drive in New York City, also commemorates Union Army soldiers and sailors.[51]

Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn is the final resting place for hundreds of Civil War veterans, including several generals.[52] Another large group of former generals (many of which were not New York residents) are buried at West Point Cemetery, including George Armstrong Custer, George Sykes, Wesley Merritt and Winfield Scott.[53] Significant Civil War cemeteries exist in other towns, among them Elmira, the site of the Elmira Prison prisoner-of-war camp. More than 2,000 Confederates who died during their incarceration are buried in nearby Woodlawn National Cemetery.[54]

Scores of New York regiments are commemorated by monuments on various battlefields throughout the country, with the largest concentration at the Gettysburg Battlefield in southern Pennsylvania. The state of New York erected a large marble memorial near the crest of Cemetery Hill, and nearly every New York unit that participated in the battle later erected individual monuments on or near where they fought.[55] Several more New York monuments dot Antietam National Battlefield.[56]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Phisterer, p. 88.

- ↑ Miller, p. 300.

- ↑ Miller, p. 301.

- ↑ Virginia Civil War Archive

- ↑ Ellis, 1967, pp 280-298.

- ↑ Phisterer, p. 47-48.

- ↑ Phisterer, pp. 53-54.

- ↑ Phisterer, p. 43.

- ↑ Tagg, Larry, The Generals of Gettysburg. Archived 2008-06-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "THE NEW CALL FOR TROOPS. - RECRUITING IN THE CITY. THE UNITED STATES MUSTERING OFFICE. THE QUARTERMASTER'S OFFICE. FILLING UP THE OLD REGIMENTS. THE HALLECK GUARD. THE STATON LEGION. THE METROPOLITAN GUARD. THE SPINOLA BRIGADE. THE FIFTH NEW-YORK ZOUAVES". The New York Times. July 22, 1862. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ↑ 14th Brooklyn short history Archived 2008-08-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Phisterer, p. 54.

- ↑ "Ellsworth biography at medalofhonor.com". Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ See: a "post history" for Fort Schuyler on NARA microfilm M903 reel 4; Brooklyn Eagle, October 22, 1863, p. 3; and History of Fort Schuyler, http://us.geocities.com/twentiethnyva/schuyler.

- ↑ Renahan, Edward, Commodore: The Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt, New York: Basic Books, 2007. ISBN 0-465-00255-2

- ↑ "Mr. Lincoln and New York: Erastus Corning". Archived from the original on 2005-08-25. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ Putnam County Recorder article on Parrott Archived 2006-11-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "U.S. Army website for the Watervliet Arsenal". Archived from the original on 2007-10-10. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

- ↑ Remington Arms Company's website

- 1 2 Leip, David. "1860 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ↑ Goodwin, Doris Kearns, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (2005) ISBN 0-684-82490-6.

- ↑ "Wood's recommendation for secession". Archived from the original on 2012-11-08. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- ↑ "Mr. Lincoln and New York: Horatio Seymour". Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ Congressional Biographical Directory.

- ↑ Lawson, Melinda, "The Civil War Union Leagues and the Construction of a New National Patriotism" Civil War History Volume 48, Issue 4, 2002. pp. 338+.

- ↑ New York Times website

- ↑ Pennsylvania webpage on Corporal Rihl's death

- ↑ "Monument to William Rihl near Greencastle, Pennsylvania". Archived from the original on 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- ↑ Phisterer, pp. 83-84.

- ↑ The New Yorker, 25 August 1934

- ↑ New York at Gettysburg, p. 108.

- ↑ Gambone, A. M., "...if tomorrow night finds me dead..." The Life of General Samuel K. Zook (Army of the Potomac), Butternut and Blue, 1996, ISBN 0-935523-53-7.

- ↑ Biography from the Gettysburg National Park website

- ↑ Hawthorne, Frederick, Gettysburg: Stories of Men and Monuments (1988).

- ↑ The Wild Geese Today. Archived 2007-05-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Mr. Lincoln and New York". Archived from the original on 2009-02-17. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ Iver Bernstein, The New York City draft riots: Their significance for American society and politics in the age of the Civil War (Oxford University Press, 1990).

- ↑ Barnes (1863), p. 117.

- ↑ Foner, E. (1988). Reconstruction America's unfinished revolution, 1863-1877. The New American Nation series. Page 32. New York: Harper & Row.

- ↑ "The Riots". Harper's Weekly, volume vii, no 344. Sonofthesouth.net. pp. 382, 394. Retrieved 2006-08-16.

- ↑ Ohio Historical Marker #3-38: Holmes County, Ohio, Draft Riots Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine Draft protests occurred in scores of towns, but few reached the stage of a riot, and none approached New York City in magnitude or damages.

- ↑ McPherson, James M Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction 399

- 1 2 Morison, Samuel Eliot (1972). The Oxford History of the American People: Volume Two: 1789 Through Reconstruction. Signet. p. 451. ISBN 0-451-62254-5.

- ↑ United States Census, 1860.

- ↑ Phisterer, pp. 67-72.

- 1 2 Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography

- ↑ GAR page at Library of Congress.

- ↑ Phisterer, p. 114.

- ↑ The New York Times, Plaza in Brooklyn Dedicated to G.A.R., May 10, 1926, p. 9.

- ↑ Grant Monument Association

- ↑ New York City Parks.

- ↑ Richman, Jeffrey I., "Final Camping Ground: Civil War Veterans at Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery, In Their Own Words" (2007)

- ↑ Interment.net: West Point USMA Cemetery

- ↑ Horigan, Michael, Death Camp of the North: The Elmira Civil War Prison Camp. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 2002. ISBN 0-8117-1432-2.

- ↑ Virtual Gettysburg - searchable database with photographs of all New York-related monuments at Gettysburg

- ↑ Virtual Antietam

Further reading

- Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...1863 (1864), detailed coverage of events in all countries; online; for online copies see Annual Cyclopaedia. Each year includes several pages on each U.S. state.

- Barnes, David M. (1863). The Draft Riots in New York, July, 1863. The metropolitan police, their services during riot week. Their honorable record (pdf) (1st ed.). New York, NY: Baker & Godwin. p. 117. OCLC 47921984. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- Bernstein, Iver (1990). The New York City draft riots: Their significance for American society and politics in the age of the Civil War (ebook ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 363. ISBN 9780198021711. OCLC 252544792. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- Brummer, Sidney David (1911). Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War (pdf). Studies in history, economics and public law, ed. by the Faculty of political science of Columbia university. Vol. 39 (1st ed.). New York, NY: Columbia university, Longmans, Green. p. 451. OCLC 862942622. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- Ellis, David M. et al. A History of New York State (Cornell University Press, 1967) pp. 335–346.

- Field, Phyllis F. The politics of race in New York: The struggle for black suffrage in the Civil War era (Cornell UP, 2009).

- Holzer, Harold, ed. State of the Union: New York and the Civil War (2002) Essays by scholars

- Livingston, E. H. President Lincoln's Third Largest City: Brooklyn and The Civil War (1994)

- McKelvey, Blake. Rochester: The Flower City, 1855-1890 (1949)

- Miller, Richard F. ed. States at War, Volume 2: A Reference Guide for New York in the Civil War (2014) 490pp excerpt

- Mitchell, Stewart. Horatio Seymour of New York (Harvard UP, 1938)

- Murdock, Eugene C. "Horatio Seymour and the 1863 draft." Civil War History 11.2 (1965): 117–141. excerpt

- Phisterer, Frederick, New York in the War of the Rebellion, 1861 To 1865, Albany: Weed, Parsons and Co., 1890. online

- Quinn, Edythe Ann. Freedom Journey Black Civil War Soldiers and the Hills Community, Westchester County, New York (State University of New York Press, 2015)

- Raus, Edmund J. Banners South: Northern Community at War (2011), about Cortland, New York

- Rawley, James A. Edwin D. Morgan 1811–1883: Merchant in Politics (Columbia University Press, 1955), the Republican governor.

- Sernett, Milton C. North star country: upstate New York and the crusade for African American freedom (Syracuse UP, 2002)

- Spann, Edward K. Gotham at War: New York City, 1860-1865 (2002) excerpt

- Weible, Robert and Jennifer A. Lemakn. Irrepressible Conflict: The Empire State in the Civil War (2014) online review; color prints showcasing 500+ objects in a museum exhibit

- "ELY, Alfred 1815 – 1892", Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, Office of Art & Archives, retrieved August 5, 2008

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)