New Hampshire State Senate | |

|---|---|

| New Hampshire General Court | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

Term limits | None |

| History | |

New session started | December 7, 2022 |

| Leadership | |

President pro tempore | |

Majority Leader | |

Minority Leader | |

| Structure | |

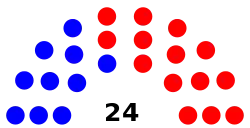

| Seats | 24 |

| |

Political groups | Majority

Minority

|

Length of term | 2 years |

| Authority | Part Second, New Hampshire Constitution |

| Salary | $200/term + mileage |

| Elections | |

Last election | November 8, 2022 (24 seats) |

Next election | November 5, 2024 (24 seats) |

| Redistricting | Legislative control |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| State Senate Chamber New Hampshire State House Concord, New Hampshire | |

| Website | |

| gencourt | |

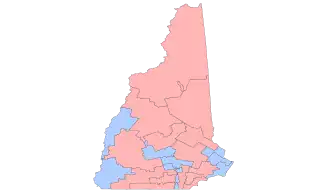

The New Hampshire Senate is the upper house of the New Hampshire General Court, alongside the lower New Hampshire House of Representatives. The Senate has been meeting since 1784.[1] The Senate consists of 24 members representing Senate districts based on population. There are 14 Republicans and 10 Democrats currently serving in the Senate.

History

Under the 1776 Constitution, two chambers of the legislature were formed: the House of Assembly and the Council, the predecessors to the modern-day House of Representatives and Senate. The Council was originally elected by the House and was composed of twelve members: five from Rockingham County; two each from Cheshire County, Hillsborough County, and Strafford County; and one from Grafton County.[2]

In 1784, the state constitution was entirely rewritten, and the upper chamber was reconstituted as the popularly elected Senate. It was originally composed of twelve members to be elected from multi-member districts drawn by the legislature,[3] but this was increased to twenty-four members in 1879. Until districts were drawn, the apportionment of the Senate was continued from the 1776 Constitution. This constitution also imposed a majority-vote requirement for State Senate elections. If no candidate won a majority of the vote, a vacancy was declared and the full General Court would pick from the top two candidates. Similarly, if a vacancy occurred while the legislature was in session, the General Court would pick the successor from the top two remaining candidates. The constitution was amended in 1889 to provide that session vacancies would be filled by special elections and in 1912 to abolish the majority-vote requirement altogether.[4]

Between 1784 and 1912, more than 200 state senate vacancies were filled by a full vote of the legislature. During some years, nearly 60% of the State Senate was selected through this method, which frequently determined which party controlled the Senate majority. An analysis of the vacancy-filling patterns shows that the General Court was overwhelmingly likely to fill vacancies based on the party affiliation of the eligible candidates. In cases in which session vacancies were filled, the General Court occasionally selected third-party or independent candidates, who received no more than a handful of votes, over opposing major-party candidates.[4]

The predictability of the vacancy-filling procedures sometimes led to conflict. In 1875, outgoing Democratic Governor James A. Weston exercised his constitutional power to issue "summonses" to the winners of legislative elections to avoid the General Court filling two vacancies. In two districts, Democratic candidates won pluralities, but not majorities; the narrow Republican majority in the State House likely meant that the Republican candidates would be elected. The Senate was tied 5–5, so the allocation of the two contested seats would determine control. Weston, along with the Executive Council, invalidated votes cast for Republican Senators in two districts on the grounds that the votes were not cast in the candidates' "Christian names." They instead issued summonses to the Democratic candidates, who were seated by the Senate. The 7–5 Democratic majority then rejected a Republican challenge to the Democrats' qualifications, and the Republican minority sought an advisory opinion from the New Hampshire Supreme Court.[4] The state supreme court concluded that "the action of the senate is final," and affirmed the seating of the Senators.[5]

In 1912, the voters approved a constitutional amendment removing the majority-vote requirement for all elections. That year, however, the gubernatorial election failed to produce a majority winner, as did four State Senate elections. After concluding that the amendment applied after the election, not to it, the General Court proceeded to fill the vacancies. An unexpected alliance between Democrats and Progressive Republicans led to Democrat Samuel D. Felker elected Governor, Henry F. Hollis elected to the U.S. Senate, four Democrats selected to fill the State Senate vacancies, and a Progressive Republican as the Speaker of the House.[6]

2022–2024 biennial session

Composition[7]

| Affiliation | Party (Shading indicates majority caucus) |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Republican | Vacant | ||

| End of 164th General Court | 10 | 13 | 23 | 1 |

| 165th General Court | 10 | 14 | 24 | 0 |

| 166th General Court | 14 | 10 | 24 | 0 |

| 167th General Court | 10 | 14 | 24 | 0 |

| Start of 168th General Court | 10 | 14 | 24 | 0 |

| Latest voting share | 42% | 58% | ||

Leadership

Committee leadership

| Committee[9] | Chair | Vice Chair | Ranking Member |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital Budget | Daniel Innis (R) | James Gray (R) | Lou D'Allesandro (D) |

| Commerce | Bill Gannon (R) | Denise Ricciardi (R) | Donna Soucy (D) |

| Education | Ruth Ward (R) | Carrie Gendreau (R) | Suzanne Prentiss (D) |

| Election Law, Municipal Affairs and Redistricting | James Gray (R) | Keith Murphy (R) | Donna Soucy (D) |

| Energy and Natural Resources | Kevin Avard (R) | Howard Pearl (R) | David Watters (D) |

| Executive Departments and Administration | Howard Pearl (R) | Sharon Carson (R) | Rebecca Perkins Kwoka (D) |

| Finance | James Gray (R) | Daniel Innis (R) | Lou D'Allesandro (D) |

| Health and Human Services | Regina Birdsell (R) | Kevin Avard (R) | Becky Whitley (D) |

| Judiciary | Sharon Carson (R) | Bill Gannon (R) | Becky Whitley (D) |

| Rules and Enrolled Bills | Kevin Avard (R) | Sharon Carson (R) | Cindy Rosenwald (D) |

| Transportation | Denise Ricciardi (R) | David Watters (D) | N/A |

| Ways and Means | Timothy Lang Sr. (R) | Lou D'Allesandro (D) | N/A |

Members of the New Hampshire Senate[7]

| District | Senator | Party | Residence | First elected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carrie Gendreau | Rep | Littleton | 2022 |

| 2 | Timothy Lang Sr. | Rep | Sanbornton | 2022 |

| 3 | Jeb Bradley | Rep | Wolfeboro | 2009 |

| 4 | David Watters | Dem | Dover | 2012 |

| 5 | Suzanne Prentiss | Dem | Lebanon | 2020 |

| 6 | James Gray | Rep | Rochester | 2016 |

| 7 | Daniel Innis | Rep | Bradford | 2022 (2016-2018) |

| 8 | Ruth Ward | Rep | Stoddard | 2016 |

| 9 | Denise Ricciardi | Rep | Bedford | 2020 |

| 10 | Donovan Fenton | Dem | Keene | 2022 |

| 11 | Shannon Chandley | Dem | Amherst | 2022 (2018–2020) |

| 12 | Kevin Avard | Rep | Nashua | 2020 (2014–2018) |

| 13 | Cindy Rosenwald | Dem | Nashua | 2018 |

| 14 | Sharon Carson | Rep | Londonderry | 2008 |

| 15 | Becky Whitley | Dem | Contoocook | 2020 |

| 16 | Keith Murphy | Rep | Manchester | 2022 |

| 17 | Howard Pearl | Rep | Loudon | 2022 |

| 18 | Donna Soucy | Dem | Manchester | 2012 |

| 19 | Regina Birdsell | Rep | Hampstead | 2014 |

| 20 | Lou D'Allesandro | Dem | Manchester | 1998 |

| 21 | Rebecca Kwoka | Dem | Portsmouth | 2020 |

| 22 | Daryl Abbas | Rep | Salem | 2022 |

| 23 | Bill Gannon | Rep | Sandown | 2020 (2016–2018) |

| 24 | Debra Altschiller | Dem | Stratham | 2022 |

Past composition of the Senate

See also

References

- ↑ "New Hampshire Senate". gencourt.state.nh.us. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- ↑ Article 3 of the Constitution of New Hampshire (1776)

- ↑ Article 2, Section 34 of the Constitution of New Hampshire (1784)

- 1 2 3 Yeargain, Tyler (2021). "New England State Senates: Case Studies for Revisiting the Indirect Election of Legislators". University of New Hampshire Law Review. 19 (2). Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ↑ Opinion of the Justices, 56 N.H. 570, 573 (N.H. 1875).

- ↑ Wright, James (1987). The Progressive Yankees: Republican Reformers in New Hampshire, 1906–1916. University Press of New England. pp. 143–44. ISBN 9781584652618.

- 1 2 "New Hampshire Senate". gencourt.state.nh.us. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ↑ "New Hampshire Senate". gencourt.state.nh.us. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ↑ "Senate Standing Committees". gencourt.state.nh.us. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

External links

- Official website

- State Senate of New Hampshire, Project Vote Smart voter information