Moorpark, California | |

|---|---|

| |

Flag  Seal | |

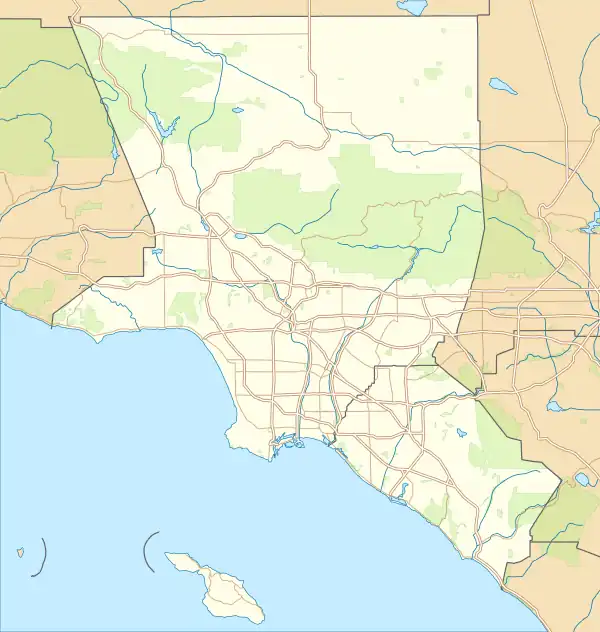

Location in Ventura County and the state of California | |

Moorpark Location in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area  Moorpark Location in California  Moorpark Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 34°16′52″N 118°52′25″W / 34.28111°N 118.87361°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Ventura |

| Founded | 1887 |

| Incorporated | 1983-07-01[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager[2] |

| • Mayor | Chris Enegren[3] |

| • State Senator | Henry Stern (D)[4] |

| • Assemblymember | Jacqui Irwin (D)[4] |

| • U. S. Congress | Julia Brownley (D)[5] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 12.47 sq mi (32.28 km2) |

| • Land | 12.28 sq mi (31.80 km2) |

| • Water | 0.19 sq mi (0.49 km2) 1.72% |

| Elevation | 515 ft (157 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 34,421 |

| • Estimate (2019)[9] | 36,375 |

| • Density | 2,962.86/sq mi (1,144.01/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| Zip Code | 93021-2804 (General Delivery), 93020 (P.O. Box)[10] |

| Area code | 805[11] |

| FIPS code | 06-49138 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1652754 |

| Website | www |

Moorpark is a city in Ventura County in Southern California. Moorpark was founded in 1900. The town grew from just over 4,000 citizens in 1980 to over 25,000 by 1990. As of 2006, Moorpark was one of the fastest-growing cities in Ventura County.[12] The population was 34,421 at the 2010 census, up from 31,415 at the 2000 census.

Etymology

The town most likely was named after the Moorpark apricot, which used to grow in the area (hence the apricot flower on the town's seal and flag).[13] The apricot, in turn, was named for Admiral Lord Anson's estate Moor Park in Hertfordshire, England; the apricot was introduced in 1688.[14][15][16]

Some of Moorpark's previous unofficial and official names include Epworth, Fremontville, Penrose, Fairview, and Little Simi.[12]

History

.jpg.webp)

Chumash people were the first to inhabit what is now known as Moorpark. A Chumash village, known as Quimisac (Kimishax), was located in today's Happy Camp Canyon Regional Park. They were hunters and gatherers who often traveled between villages to trade. The village of Quimisac once controlled the local trade of fused shale in the region.[17][18] The area was later part of the large Rancho Simi land grant given in 1795 to the Pico brothers by Governor Diego de Borica of Alta California.

Robert W. Poindexter, the secretary of the Simi Land and Water Company, received the land when the association was disbanded. A map showing the townsite was prepared in November 1900. It was a resubdivision of the large lot subdivision known as Fremont, or Fremontville.[19][20] An application for a post office was submitted on June 1, 1900, and approved by August of that year. The application noted that the town had a railroad depot.[18] The town grew after the 1904 completion of a 7,369-foot (2,246 m) tunnel through the Santa Susana Mountains. Moorpark was then on the main route of the Southern Pacific Railroad's Coast Line between Los Angeles and San Francisco. The depot remained in operation until it was closed in 1958. It was eventually torn down around 1965.

Moorpark was one of the first cities to run off commercial nuclear power in the entire world, and the second in the United States, after Arco, Idaho, on July 17, 1955, which is the first city in the world to be lit by atomic power. For one hour on November 12, 1957, this fact was featured on Edward R. Murrow's See It Now television show.[21] The reactor, called the Sodium Reactor Experiment was built by the Atomics International division of North American Aviation at the nearby Santa Susana Field Laboratory. The Sodium Reactor Experiment operated from 1957 to 1964 and produced 7.5 megawatts of electrical power at a Southern California Edison-supplied generating station.[22]

Moorpark College opened on September 11, 1967. Moorpark College is one of the few colleges that features an exotic animal training and management program. Moorpark was incorporated as a city on July 1, 1983.

In 1996, Moorpark's Little League All-Star team represented the West Region in the Little League World Series in Williamsport, PA.[23]

In February 2005, a Siberian tiger named Tuffy that escaped from a local residence was shot and killed in one of Moorpark's parks. This created a great deal of uproar, because the animal control officers used a gun instead of a tranquilizer to kill the tiger, primarily because the tiger could not be shot from the proper angle for a tranquilizer to prove effective. Candlelight vigils were held for the late Tuffy. The couple who owned the tiger had moved from a licensed facility in Temecula, California, to an unlicensed facility in the Moorpark area of Ventura County. They lost their U.S. Department of Agriculture exhibitor license because they failed to notify the department of the move within 10 days. The wife pleaded guilty to a federal misdemeanor count of failing to maintain records of exotic felines. The husband pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice, making false statements and failing to maintain proper records. Each was sentenced to home detention, three years probation, and fined $900.[24]

Just a month later, in March 2005, the fairly complete remains (about 75%) of an unusually old mammoth, possibly the rare southern mammoth (Mammuthus meridionalis), were discovered in the foothills of Moorpark at the site of a housing development.[25] The fossilized skeleton is believed to be from a 800,000 to 1.4 million years old mammoth, which is estimated to have had a weight of ten tons.[12]

In 2006, the Moorpark city council transferred governance of their library from the Ventura County library system to their own newly created city library system. The library, which opened in 1912, celebrated its centennial in 2012.[26]

On February 28, 2006, a housing proposal, North Park Village, which would have added 1,680 houses on 3,586 acres (15 km2) in the north-east area of the city, was defeated by a landslide in a city election.[27][28]

Egg City

In 1961, Julius Goldman founded Egg City, the largest chicken ranch in the United States at the time located just north of Moorpark, California. Many chicken coops were spread over acres of concrete, with millions of chickens in them. Local residents were somewhat irked by the farm, when the smell of it wafted to Moorpark on windy days. The odors also commonly flowed to the nearby town of Fillmore. The business suffered a setback in 1972, when millions of chickens were slaughtered because of the threat of Newcastle disease. Egg gathering was done from 36 houses by hand, with workers placing eggs onto plastic flats while riding electric carts. Liquid, dry and shell eggs were processed at the 8,000 sq ft hatchery facility warehouse with yolk and albumen available in individually. The farm finally closed in 1996. In early December 2006, a wildfire destroyed the dilapidated remains of Egg City.[29]

Geography

Central Moorpark lies in a valley created by the Arroyo Simi river. It is situated on flatlands and mesas at the base of numerous hills. It is located immediately west of Simi Valley, California.[13][30]

The city is divided by Highway 118, locally known as Los Angeles Avenue. Old Town Moorpark (Downtown) is located north of Route 118. Many newer residential communities can be found south of Route 118.[13]

Neighborhoods

- Downtown is on High Street at the historic center of the city.[31] The pepper trees that line High Street were planted by Robert Poindexter who was responsible for the plotting and mapping of the town. This area also features the High Street Arts Center (a Performing Arts center operated by the City of Moorpark), and various restaurants and businesses.[32]

- The Peach Hill and Mountain Meadows neighborhoods are south of the Arroyo Simi. Moorpark High School is in this area, as well as many parks, including the Arroyo Vista Park and Recreation Center, the city's largest park. This area contains a large part of the city's population as over 75 percent of homes in Moorpark were constructed after 1980 here and in other new projects.[13]

- Campus Park is named for Moorpark College. An additional substantial development is occurring to the north of the existing city, in the area of the Moorpark Country Club.

Climate

With its close proximity to Los Angeles, Moorpark too has a Subtropical-Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csb on the coast, Csb inland), and receives just enough annual precipitation to avoid either Köppen's BSh or BSk (semi-arid climate) classification.

| Climate data for Moorpark, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 92 (33) |

92 (33) |

96 (36) |

105 (41) |

102 (39) |

106 (41) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

109 (43) |

108 (42) |

99 (37) |

99 (37) |

109 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 69 (21) |

69 (21) |

71 (22) |

74 (23) |

75 (24) |

77 (25) |

81 (27) |

83 (28) |

82 (28) |

79 (26) |

74 (23) |

69 (21) |

75 (24) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 41 (5) |

43 (6) |

44 (7) |

46 (8) |

50 (10) |

53 (12) |

57 (14) |

56 (13) |

55 (13) |

50 (10) |

44 (7) |

41 (5) |

48 (9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 25 (−4) |

26 (−3) |

25 (−4) |

30 (−1) |

35 (2) |

37 (3) |

38 (3) |

40 (4) |

40 (4) |

32 (0) |

28 (−2) |

25 (−4) |

25 (−4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.7 (94) |

5.0 (130) |

2.7 (69) |

0.8 (20) |

0.3 (7.6) |

0.1 (2.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (5.1) |

0.7 (18) |

1.4 (36) |

2.5 (64) |

17.4 (446.2) |

| Source: The Weather Channel.[33] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 2,902 | — | |

| 1970 | 3,380 | 16.5% | |

| 1980 | 4,030 | 19.2% | |

| 1990 | 25,494 | 532.6% | |

| 2000 | 31,415 | 23.2% | |

| 2010 | 34,421 | 9.6% | |

| 2020 | 36,284 | 5.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[34] | |||

2010

The 2010 United States Census[35] reported that Moorpark had a population of 34,421. The population density was 2,689.4 inhabitants per square mile (1,038.4/km2). The racial makeup of Moorpark was 25,860 (75.1%) White, 533 (1.5%) African American, 248 (0.7%) Native American, 2,352 (6.8%) Asian, 50 (0.1%) Pacific Islander, 3,727 (10.8%) from other races, and 1,651 (4.8%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 10,813 persons (31.4%).

The Census reported that 34,421 people (100% of the population) lived in households, 0 (0%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 0 (0%) were institutionalized.

There were 10,484 households, out of which 4,863 (46.4%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 6,966 (66.4%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 1,113 (10.6%) had a female householder with no husband present, 507 (4.8%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 483 (4.6%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 58 (0.6%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 1,337 households (12.8%) were made up of individuals, and 434 (4.1%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.28. There were 8,586 families (81.9% of all households); the average family size was 3.55.

The population was spread out, with 9,459 people (27.5%) under the age of 18, 3,631 people (10.5%) aged 18 to 24, 8,825 people (25.6%) aged 25 to 44, 10,051 people (29.2%) aged 45 to 64, and 2,455 people (7.1%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34.7 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.1 males.

There were 10,738 housing units at an average density of 839.0 per square mile (323.9/km2), of which 8,182 (78.0%) were owner-occupied, and 2,302 (22.0%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.0%; the rental vacancy rate was 2.9%. 26,688 people (77.5% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 7,733 people (22.5%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

As of the 2000 census,[36] there were 31,416 people in the city, organized into 8,994 households and 7,698 families. The population density was 1,651.9 inhabitants per square mile (637.8/km2). There were 9,094 housing units at an average density of 478.2 per square mile (184.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 74.42% White, 27.81% Hispanic of any race, 13.95% from other races, 5.63% Asian, 3.87% from two or more races, 1.52% African American, 0.47% Native American, 0.15% Pacific Islander.

There were 8,994 households, out of which 54.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 72.0% were married couples living together, 9.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 14.4% were non-families. 9.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 2.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.49 and the average family size was 3.71.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 34.2% under the age of 18, 8.6% from 18 to 24, 32.3% from 25 to 44, 20.4% from 45 to 64, and 4.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98.1 males.

According to a 2007 estimate,[37] the median income for a household in the city was $90,109, and the median income for a family was $96,532. Males had a median income of $55,535 versus $35,790 for females. The per capita income for the city was $25,383. 7.0% of the population and 4.3% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 8.6% of those under the age of 18 and 7.3% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.

Economy

In 2017, Moorpark had 12,235 jobs (up from 10,820 jobs in 2010) and retail sales of $281 million (up from $264 million in 2010).[38] Most of these retail businesses are located along the community's Los Angeles Avenue corridor, with the community's historic downtown area, known as Historic High Street, as a secondary retail hub.[39]

Several businesses have been opened by celebrity chefs, including Fabio Viviani,[40] a Top Chef "fan favorite," and Damiano Carrara, a third-place finisher on Food Network Star.[41]

Top employers

According to the City's 2021 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report,[42] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees (2021) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | PennyMac Loan Services | 1,086 |

| 2 | Aerovironment | 800 |

| 3 | Moorpark College | 727 |

| 4 | Moorpark Unified School District | 718 |

| 5 | Pentair Water Pool & Spa | 530 |

| 6 | Benchmark Electronics Manufacturing Solutions | 320 |

| 7 | Ensign-Bickford Aerospace & Defense Company | 224 |

| 8 | Amazon Retail, Inc. | 200 |

| 9 | Target Stores | 169 |

| 10 | Covered 6, LLC | 135 |

Arts and culture

A few events are held in the Moorpark area during the year, most notably Moorpark "Country Days", a single day parade and festival in late September or early October, American Civil War battle reenactments in early-November (in 2019 this annual event was cancelled), an "Apricot Festival", usually in the spring or summer, an annual fireworks celebration on the third of July every year, and the Moorpark Film Festival in August. The "Country Days" parade includes various vendors, entertainment, and family friendly games/crafts. Children march with their schools, sports teams, dance companies, etc. Local businesses are also encouraged to march. The July 3rd fireworks are popular around the rest of Ventura County, as people can go to the Moorpark fireworks on the 3rd, and still see their own local city's fireworks on July 4.

The City of Moorpark established an “Arts in Public Places” (AIPP) program in 2005 and later created the Arts Commission in 2006 to support the AIPP efforts.[43] In August 2019, Moorpark engaged the services of ArtsOC to develop an Arts Master Plan. While the initial role of the Arts Commission was to oversee the AIPP program, their role has expanded to include general oversight and implementation of the Arts Master Plan to engage, strengthen, and harness the visual and performing arts in Moorpark.

Parks and recreation

Parks

Moorpark has 20 parks, all with a variety of amenities. Park hours for unlit facilities are from 6:00 a.m. to sunset. Lit facilities are from 6:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. The City's Dog Park is open from 7:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. PST, and 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. DST. The City's Skatepark is open from 10:00 a.m. to sunset on school days, and 8:00 a.m. to sunset on all other days.

Park facilities, including picnic pavilions, ball fields, soccer fields, and tennis courts can be reserved for private use.[44]

- Arroyo Vista Community Park

- Campus Canyon

- Campus Park

- College View Park

- Community Center Park

- Country Trail Park

- Dog Park

- Glenwood Park

- Magnolia Park

- Mammoth Highlands Park

- Miller Park

- Monte Vista Nature Park

- Mountain Meadows Park

- Peach Hill Park

- Poindexter Park

- Tierra Rejada Park

- Veterans Memorial Park

- Villa Campesina Park

- Virginia Colony Park

- Walnut Acres Park

Government and politics

The city government operates under a council-manager form of government. The Mayor is elected at-large for two-year terms, and four City Councilmembers are elected to staggered four-year terms. The Mayor and City Councilmember positions are non-partisan. Through 2018, the City Councilmembers were elected on an at-large basis. In April 2019, the City Council voted to transition to a district-based election system for the four City Councilmembers, beginning with the November 2020 municipal election.[45] In the November 2020 election, Daniel Groff (District 2, Western Moorpark) and Dr. Antonio Castro (District 4, Downtown/Central Moorpark) became the first two Moorpark City Councilmembers elected to represent districts.[46]

The city government operates municipal facilities throughout the community, including the Moorpark City Library, Moorpark Active Adult Center, Arroyo Vista Recreation Center and Community Park, Ruben Castro Human Services Facility, Moorpark Public Services Facility, and the Moorpark Police Services Center, which contains offices for the Ventura County Sheriff's Office and the California Highway Patrol. The Ventura County Fire Department provides fire protection for Moorpark, with two fire stations in the city.

In the California State Legislature, Moorpark is in the 27th Senate District, represented by Democrat Henry Stern, and in the 44th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Jacqui Irwin. In the United States House of Representatives, Moorpark is represented by Democrat Julia Brownley in California's 26th congressional district.

In October 2020, there were 23,290 registered voters in Moorpark, with 8,845 registered as Democrats (38.0%), 8,045 registered as Republicans (34.5%), 4,993 registered with no party preference (21.4%), and the remainder split among other parties.[47]

Education

Moorpark is served by Moorpark Unified School District which includes Moorpark High School.

Additionally, there is The High School at Moorpark College, a middle college located on the Moorpark College campus. In this program, students take English and Social Studies classes at the high school level and Math, Science, Foreign Language and other electives at Moorpark College to fulfill the requirements for graduation and the Associates Degree simultaneously.[48]

Moorpark College

Moorpark is the home of Moorpark College, a public community college and part of the Ventura County Community College District. Moorpark College is ranked the highest among the California Community Colleges for degree completion.[49] Moorpark College is also home to America's Teaching Zoo, the Charles Temple Observatory, and the Moorpark College Performing Arts Center, each used for classes and community events.

Transportation

- The city is serviced by Amtrak California's Pacific Surfliner and by Metrolink's Ventura County Line commuter rail system with service to Los Angeles, with a train station located on High Street in the center of the city.[30]

- The city of Moorpark has a mass transit bus system, known as the Moorpark City Transit.

Major highways

Public safety

Law enforcement

The Ventura County Sheriff's Office provides law enforcement services for the city.[30]

Crime

Moorpark had the lowest crime rates in Ventura County according to public crime statistics in 2000,[30] and according to Ventura County Sheriff's Department statistics from 2006.[50] The FBI has ranked Moorpark as one of California's safest cities.[51] It was ranked California's 8th safest city in 2017.[52] No homicides were recorded in 2017 nor 2018. The 2018 FBI Uniform Crime Report reported a near record-low crime level.

Volunteers in Policing

The City provides a "Volunteers in Policing" (VIP) program that formally engages citizens in supporting the police department and the community that began in 1994.[53] In 1994 the program began with an attempt to open a police storefront run by the Volunteers in policing.[54] Now the volunteers do a wide variety of non-dangerous tasks in an effort to assist the local sheriff's department including: parking enforcement, wellness checks, and traffic enforcement.[53]

In popular culture

A number of movies have been filmed in Moorpark. Kings Row (1942) starring Ronald Reagan featured a scene filmed at Spring Road and Los Angeles Avenue. The film Paranormal Activity 3 has a portion taking place in Moorpark.[18] J.J Gittes (Jack Nicholson) gets shot at an orchard in a scene in Chinatown (1974), which was shot at Trident Ranch.[55] The big game scene in The Best of Times (1986) was shot at Moorpark Memorial High School, while scenes in The Great Man's Lady (1942) were filmed at Joel McCrea's ranch.[56] Scenes from the TV series Super Soul Sunday starring Oprah Winfrey are filmed at Apricot Lane Farms.[57] In 2018, the documentary The Biggest Little Farm was released, telling the story of Apricot Lane Farms.[58] A special, "The Biggest Little Farm: The Return", was released in 2022.[59] The Disney movie Magic Camp has scenes filmed in the High Street Arts Center on High Street.

In 2016, Mike Winters, the Vice President and Historian of the Moorpark Historical Society, published a revised history of Moorpark that covers the years from Moorpark's beginnings to the 1930s. The book, published by Arcadia Publishing is entitled Images of America: Moorpark.

Notable people

- Brian Blechen, professional football player for the Carolina Panthers

- Kelli Berglund, actress

- Walter Brennan, screen actor[60]

- John Chester, documentary filmmaker, TV director, and cinematographer

- Jan Ebeling, German-American equestrian, who competed at the 2012 Summer Olympics

- Sean Gilmartin, MLB pitcher

- Tim Hanshaw, former NFL player (1995 drafted in the 4th round by the San Francisco 49ers)

- Rick Jason, actor

- Drake London, wide receiver for the Atlanta Falcons

- Zach Penprase (born 1985), Israeli-American baseball player for the Israel National Baseball Team

- Dennis Pitta, former professional football player

- Dillon "Attach" Price (born 1997), professional Call of Duty player

- Gary Sinise, actor[61]

- Paul Winchell, ventriloquist, inventor, and the voice of Tigger.[62]

See also

References

- ↑ "Moorpark, CA". Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- ↑ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report: Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 2014". Moorpark, CA. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- ↑ "City Council". City of Moorpark. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- 1 2 "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ↑ "California's 26th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ↑ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ↑ "Moorpark". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Moorpark (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ↑ "USPS - ZIP Code Lookup - Find a ZIP+ 4 Code By City Results". Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- ↑ "Moorpark Area Code". Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- 1 2 3 Brant, Cherie (2006). Keys to the County: Touring Historic Ventura County. Ventura County Museum. ISBN 978-0972936149..

- 1 2 3 4 McCormack, Don (1999). McCormack's Guides Santa Barbara and Ventura 2000. McCormacks Guides. p. 107. ISBN 9781929365098.

- ↑ "Moorpark Apricot". Arbor Day Foundation. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ↑ "Dried Apricots: History". Coosemans Specialty Produce. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ↑ Walter, Scott (May 27, 1828). The Journal of Sir Walter Scott. The Literature Network. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ↑ Winters, Michael (2016). Moorpark. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9781439657355.

- 1 2 3 Gunter, Norma (1969). The Moorpark Story. Moorpark Chamber of Commerce. p. 12.

- ↑ "Map of a part of Tract "L" of RANCHO SIMI, Ventura Co. Cal" (PDF). Ventura County Recorder. November 1900.

- ↑ "Map of FREMONT, a Subdivision of Lot "L" of RANCHO SIMI, Ventura County, California, showing the townsite of MOORPARK and the lands of Madeleine R. Poindexter" (PDF). Ventura County Recorder. September 1893.

- ↑ Barnett, Maggie (December 14, 2003). "Atomic Age footnote grows into 21st century". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Nuclear Energy in California". www.energy.ca.gov. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ↑ League, Little. "Participants". Little League. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Owner of escaped tiger sentenced to home detention". Orange County Register. May 15, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ↑ Saillant, Catherine; Griggs, Gregory W. (April 9, 2005). "Mammoth's skeleton uncovered in L.A". The Seattle Times.

- ↑ Willer-Allred, Michele (January 28, 2012). "Moorpark launches library's centennial celebration". Ventura County Star.

- ↑ Rode, Erin (January 23, 2021). "From Hueneme to Simi, Ventura County cities approved these housing projects in 2020". Ventura County Star. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ↑ Willer-Allred, Michele (December 20, 2012) "Housing development again proposed for site near Moorpark College" Ventura County Star

- ↑ Rasmussen, Cecilia. "Fire writes the final chapter for the world's largest egg ranch". Los Angeles Times. No. December 17, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 McCormack, Don (1999). McCormack's Guides Santa Barbara and Ventura 2000. McCormacks Guides. p. 108. ISBN 9781929365098.

- ↑ Harris, Mike (September 2, 2021). "Moorpark City Council temporarily bans new retail chain stores on main downtown street". Ventura County Star. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ↑ Cox, Christina (September 18, 2020). "High Street Station clears commission". Moorpark Acorn. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ↑ "MONTHLY AVERAGES for Moorpark, CA". The Weather Channel. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Moorpark city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "American FactFinder - Community Facts". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Profile of the City of Moorpark" (PDF). Profile of the City of Moorpark. May 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ↑ Wilson, Alex (December 14, 2023). "High Hopes for High Street: The Alley and other new developments are turning sleepy Moorpark into a hip destination". VC Reporter. Times Media Group. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ↑ McKinnon, Lisa (January 10, 2020). "Open and shut: Restaurant closures a sign of the times, says Fabio Viviani of Cafe Firenze". Ventura County Star. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ↑ Elliott, Farley (August 22, 2017). "Food Network star Damiano Carrara expands empire into a massive Moorpark space". Eater LA. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ↑ "City of Moorpark ACFR". moorparkca.gov. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ↑ "Chapter 17.50 ART IN PUBLIC PLACES". library.qcode.us. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ↑ "Parks | Moorpark, CA - Official Website". www.moorparkca.gov. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ↑ "District-Based Elections | Moorpark, CA - Official Website". www.moorparkca.gov. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ↑ "Election 2020 results: Parvin leads for Moorpark mayor; Groff, Castro on council | Moorpark, CA - Official Website". vcstar.com. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ↑ "Report of Registration County Summary" (PDF). California Secretary of State. October 19, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ↑ "High School at Moorpark College". hsmc-moorpark-ca.schoolloop.com. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ↑ D'Angelo, Alexa. "Moorpark College has the highest completion rate in the state". Ventura County Star. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ↑ "Moorpark is safest city in county - Moorpark Acorn". mpacorn.com. March 3, 2006. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ↑ Kelley, Daryl (February 18, 2002). "FBI Ranks Moorpark 7th-Safest Among State's Smaller Cities". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Moorpark maintains status as safe city - Moorpark Acorn". mpacorn.com. June 23, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- 1 2 Willer-Allred, Michele (March 28, 2012). "Volunteers help keep Moorpark safe". Ventura County Star. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ↑ Hadly, Scott (July 19, 1994). "MOORPARK : Volunteers Sought for Police Storefront". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ↑ "The ultimate 'Chinatown' filming location map of Los Angeles". Curbed. June 19, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ↑ "The Great Man's Lady (1942) - Notes - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Film & Photos - Apricot Lane Farms". apricotlanefarms.com. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Toronto: Neon Lands Documentary ‘The Biggest Little Farm’". Variety, September 11, 2018.

- ↑ Pennacchio, George (April 22, 2022). "'The Biggest Little Farm: The Return' marks a new look at a Ventura County farming couple". ABC7 Los Angeles. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ↑ "Walter Brennan". Archived from the original on June 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Gary Sinise's house in Moorpark, CA (#4)". virtualglobetrotting.com. January 22, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ↑ Oliver, Myrna (June 26, 2005). "Paul Winchell, 82; the Voice of Tigger Gained Fame as Ventriloquist". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 12, 2018.