Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918–1919 | |||||||||

Emblem

| |||||||||

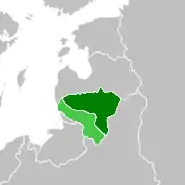

Map of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1919, with uncontrolled territory shown in light green. | |||||||||

| Status | Puppet state | ||||||||

| Capital | Vilnius | ||||||||

| Common languages | Lithuanian · Russian Belarusian · Polish Yiddish[1] | ||||||||

| Government | Socialist republic | ||||||||

| Chairman | |||||||||

| Legislature | Provisional revolutionary government (Lithuania) | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War I | ||||||||

• Provisional revolutionary government formed | 8 December 1918 | ||||||||

• Republic established | 16 December 1918 | ||||||||

• Recognised by Soviet Russia | 22 December 1918 | ||||||||

• Capture of Vilnius | 5 January 1919 | ||||||||

• Merged with SSR Byelorussia | 27 February 1919 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (LSSR) was a short-lived Soviet Puppet state[2] during early Interwar period. It was declared on 16 December 1918 by a provisional revolutionary government led by Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas. It ceased to exist on 27 February 1919, when it was merged with the Socialist Soviet Republic of Byelorussia to form the Lithuanian–Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (Litbel). While efforts were made to represent the LSSR as a product of a socialist revolution supported by local residents, it was largely a Moscow-orchestrated entity created to justify the Lithuanian–Soviet War. As a Soviet historian described it as: "The fact that the Government of Soviet Russia recognized a young Soviet Lithuanian Republic unmasked the lie of the USA and British imperialists that Soviet Russia allegedly sought rapacious aims with regard to the Baltic countries."[3] Lithuanians generally did not support Soviet causes and rallied for their own national state, declared independent on 16 February 1918 by the Council of Lithuania.

Background

Germany had lost World War I and signed the Compiègne Armistice on 11 November 1918. Its military forces then started retreating from the former Ober Ost territories. Two days later, the government of the Soviet Russia renounced the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which had assured Lithuania's independence.[4] Soviet forces then launched a westward offensive against Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine in an effort to spread the global proletarian revolution and replace national independence movements with Soviet republics.[5] Their forces followed retreating German troops and reached Lithuania by the end of December 1918.[6]

Formation

In Lithuania, the communists were not active until late summer 1918. The Communist Party of Lithuania (CPL) was organized by the 34 delegates at its first congress, held in Vilnius between 1 and 3 October 1918.[3] Pranas Eidukevičius was elected as the first chairman. The party decided to follow examples set by the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik) and organize a socialist revolution in Lithuania. The plans were instigated and financed by Moscow and supervised by Adolph Joffe and Dmitry Manuilsky.[7] On 2 December Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas sent a delegate to bring 15 million rubles to finance the "revolution".[7] On 8 December the CPL formed the eight-member provisional revolutionary government led by Mickevičius-Kapsukas. Its other members were Zigmas Aleksa-Angarietis, Pranas Svotelis-Proletaras, Semyon Dimanstein, Kazimierz Cichowski, Aleksandras Jakševičius, Konstantinas Kernovičius and Yitzhak Weinstein (Aizikas Vainšteinas).[8] Modern historians doubt if the provisional government really met in Vilnius as claimed by the Soviet sources;[7][9] it is more likely that the government followed the advancing Red Army. Between 16 December 1918 and 7 January 1920 the government resided in Daugavpils, which had been captured by the Red Army on 9 December 1918.[7]

The government issued a manifesto, printed with a 16 December date, declaring the establishment of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic.[3] The manifesto was first published in the Russian newspaper Izvestia on 19 December and then announced on radio.[7] It was then published in Vilnius five days later.[10] A draft of the manifesto, prepared by Kapsukas, stressed the need of close ties with communist Russia and ended with the slogan "Long live the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic with incorporated Soviet Lithuania!"[3] The final version, edited by Stalin and the Russian Communist Party, eliminated references to the union with Russia and replaced the slogan with "Long live freed Soviet Lithuanian Republic!"[7] Kapsukas did not want to establish an independent Soviet republic as he had campaigned for many years against social patriotism, separatism and Lithuanian independence. Influenced by Rosa Luxemburg, he had rejected the idea of self-determination.[11]

The newly formed LSSR asked for assistance from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and it duly recognized the LSSR as an independent state on 22 December.[12] The same day, the Red Army took over Zarasai and Švenčionys on the Lithuanian–Soviet border. The provisional government then seemed to dissolve and did not attempt to gain wider recognition.[3] The Lithuanian Army, in its infancy, was unable to offer resistance to the Soviet advance. On 5 January 1919 the Red Army captured Vilnius and, by the end of January 1919, the Soviets controlled about two-thirds of Lithuania's territory.[6]

Similar republics were established in Latvia (the Latvian Socialist Soviet Republic) and Estonia (the Commune of the Working People of Estonia).

Government

The LSSR was new, weak and had to rely on Russian assistance.[12] In Russia, the Soviets were generally supported by the industrial working class, but this was too small in Lithuania.[13] On 21 January the RSFSR granted a loan of 100 million rubles to the provisional government.[14] The LSSR did not form its own army. In February 1919, Kapsukas sent a telegram to Moscow arguing that conscription of local Lithuanians to the Red Army would only encourage Lithuanians to volunteer for the Lithuanian Army.[1] Meanwhile, in the territory it had occupied, the Soviets created revolutionary committees and councils based on Russian models.[1]

The Soviets demanded large war contributions from captured cities and villages. For example, Panevėžys was required to pay 1 million rubles, Utena 200,000 rubles, while 10 rubles were demanded from villages.[13] They nationalized commercial institutions and large estates, assigning land for use in collective farming rather than redistribution to smaller farms.[13] Economic difficulties and cash shortage was illustrated by a decree published in January 1919 prohibiting financial institutions to pay more than 250 rubles per week to any resident.[15] In a country of staunch Catholics and determined nationalists, the Soviet promotion of internationalism and atheism alienated the local population and contributed, ultimately, to the Soviets' eventual withdrawal.[1][13]

Members of the Council of People's Commissars

| Members of the Council of People's Commissars | ||

|---|---|---|

| Position | As of 6 January 1919[16] | As of 22 January 1919[16] |

| Commissar of foreign affairs | Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas (also chairman) | |

| Commissar of internal affairs | Zigmas Aleksa-Angarietis (also deputy chairman) | |

| Commissar of food | Aleksandras Jakševičius | M. Slivkin |

| Commissar of labor | Semyon Dimanstein | |

| Commissar of finance | Kazimierz Cichowski | |

| Commissar of transport | Pranas Svotelis-Proletaras | Aleksandras Jakševičius |

| Commissar of agriculture | Yitzhak Weinstein-Branovski | Vaclovas Bielskis |

| Commissar of education | Vaclovas Biržiška | |

| Commissar of communications | – | Pranas Svotelis-Proletaras |

| Commissar of military affairs | – | Rapolas Rasikas |

| Commissar of the people's economy | – | Yitzhak Weinstein-Branovski |

| Commissar of trade and industry | – | Yitzhak Weinstein-Branovski |

Dissolution and aftermath

Between 8 and 15 February 1919, Lithuanian and German volunteers stopped the Soviet advance and prevented them from taking Kaunas, the temporary capital of Lithuania.[6] At the end of February, the Germans started an offensive in Latvia and northern Lithuania.[17] Faced with military difficulties and unreceptive locals, the Soviets decided to combine the weak Lithuanian and Byelorussian SSRs into the Lithuanian–Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (Litbel), led by Kapsukas.[18] The communist parties were also merged into the Communist Party (bolsheviks) of Lithuania and Belorussia. However, that had little effect and Polish forces took Vilnius in April and Minsk in August 1919 during the Polish–Soviet War.[19] Litbel was also dissolved.

.png.webp)

When the tide turned in the Polish–Soviet War, the Soviets captured Vilnius on 14 July 1920. They did not transfer the city to the Lithuanian administration, as agreed in the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty, signed just two days before. Instead, the Soviets planned a coup to overthrow the Lithuanian government and re-establish a Soviet republic as they did with the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.[20] However, they lost the Battle of Warsaw and were pushed back by the Poles. Some historians credit this victory for saving Lithuania's independence from the Soviet coup.[19][21] During the interwar years, Lithuanian–Soviet relations were generally friendly, but, a few months after the outbreak of World War II, the Soviet Union decided to occupy the Baltic states, including Lithuania, in July 1940. Official Soviet propaganda described the occupation as the "restoration of Soviet power by revolutionary masses".[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Eidintas, Alfonsas; Vytautas Žalys; Alfred Erich Senn (1999). Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918–1940 (Paperback ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 36. ISBN 0-312-22458-3.

- ↑ "Lietuvos Sovietų Respublika" (in Lithuanian). Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jurgėla, Constantine R. (1976). Lithuania: The Outpost of Freedom. Valkyrie Press. pp. 161–165. ISBN 0-912760-17-6.

- ↑ Langstrom, Tarja (2003). Transformation in Russia and International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 52. ISBN 90-04-13754-8.

- ↑ Davies, Norman (1998). Europe: A History. HarperPerennial. p. 934. ISBN 0-06-097468-0.

- 1 2 3 (in Lithuanian) Ališauskas, Kazys (1953–1966). "Lietuvos kariuomenė (1918–1944)". Lietuvių enciklopedija. Vol. XV. Boston, Massachusetts: Lietuvių enciklopedijos leidykla. pp. 94–99. LCCN 55020366.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Čepėnas, Pranas (1986). Naujųjų laikų Lietuvos istorija (in Lithuanian). Vol. II. Chicago: Dr. Griniaus fondas. pp. 318–323. ISBN 5-89957-012-1.

- ↑ White, J. D. (October 1971). "The Revolution in Lithuania 1918–19". Soviet Studies. 2 (23): 192–193. ISSN 0038-5859.

- ↑ Lesčius, Vytautas (2004). Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918–1920 (PDF). Lietuvos kariuomenės istorija (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania. p. 32. ISBN 9955-423-23-4.

- ↑ Antanas Drilinga, ed. (1995). Lietuvos Respublikos prezidentai (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Valstybės leidybos centras. p. 51. ISBN 9986-09-055-5.

- ↑ White, James D. (1994). "National Communism and World Revolution: The Political Consequences of German Military Withdrawal from the Baltic Area in 1918–19". Europe-Asia Studies. 8 (46): 1363. ISSN 0966-8136.

- 1 2 Eidintas, Alfonsas (1991). Lietuvos Respublikos prezidentai (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Šviesa. p. 36. ISBN 5-430-01059-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Lane, Thomas (2001). Lithuania: Stepping Westward. Routledge. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0-415-26731-5.

- ↑ Lesčius, Vytautas (2004). Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918–1920 (PDF). Lietuvos kariuomenės istorija (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania. p. 29. ISBN 9955-423-23-4.

- ↑ Kvizikevičius, Linas; Saulius Sarcevičius (2007). "Pinigų cirkuliacijos Lietuvoje bruožai 1915−1919 m." Istorija. Lietuvos aukštųjų mokyklų mokslo darbai (in Lithuanian) (68): 35. ISSN 1392-0456.

- 1 2 Senn, Alfred Erich (1975). The Emergence of Modern Lithuania (2nd ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 239–240. ISBN 0-8371-7780-4.

- ↑ Rauch, Georg von (1970). The Baltic States: The Years of Independence. University of California Press. p. 60. ISBN 0-520-02600-4.

- ↑ Mawdsley, Evan (2007). The Russian Civil War. Pegasus Books. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-933648-15-6.

- 1 2 Snyder, Timothy (2004). The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale University Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0-300-10586-X.

- ↑ Eidintas, Alfonsas; Vytautas Žalys; Alfred Erich Senn (1999). Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918–1940 (Paperback ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 70. ISBN 0-312-22458-3.

- ↑ Senn, Alfred Erich (September 1962). "The Formation of the Lithuanian Foreign Office, 1918–1921". Slavic Review. 3 (21): 500–507. doi:10.2307/3000451. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 3000451. S2CID 156378406.