The largest living snakes in the world, measured either by length or by weight, are various members of the Boidae and Pythonidae families. They include anacondas, pythons and boa constrictors, which are all non-venomous constrictors. The longest venomous snake, with a length up to 18.5–18.8 ft (5.6–5.7 m), is the king cobra,[1] while contesters for the heaviest title include the Gaboon viper and the Eastern diamondback rattlesnake. All of these three species reach a maximum mass in the range of 6–20 kg (13–44 lb).

There are fourteen living snake species with a maximum mass of at least 50 lb (23 kg), as shown in the table below. This includes all species that reach a length of at least 20 ft (6.1 m). There are two other species that reach nearly this length – the Oenpelli python (binomial name Nyctophilopython oenpelliensis, Simalia oenpelliensis or Morelia oenpelliensis),[2] and the olive python (Liasis olivaceus). The information available about these two species is rather limited.[3] The Oenpelli python, in particular, has been called the rarest python in the world.[4][5][6] By weight, the blood python (Python brongersmai) is also a relatively massive snake, although it does not reach exceptional lengths.

It is important to be aware that there is considerable variation in the maximum reported size of these species, and most measurements are not truly verifiable, so the sizes listed should not be considered definitive. In general, the reported lengths are likely to be somewhat overestimated.[7] In spite of what has been, for many years, a standing offer of a large financial reward (initially $1,000 offered by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt in the early 1900s,[8] later raised to $5,000, then $15,000 in 1978 and $50,000 in 1980) for a live, healthy snake over 30 ft (9.14 m) long by the New York Zoological Society (later renamed as the Wildlife Conservation Society), no attempt to claim the reward has ever been made.[3]

Although it is generally accepted that the reticulated python is the world's longest snake, most length estimates longer than 6 m (20 ft) have been called into question.[7] It has been suggested that confident length records for the largest snakes must be established from a dead body soon after death, or alternatively from a heavily sedated snake, using a steel tape and in the presence of witnesses, and must be published (and preferably recorded on video).[7] At least one reticulated python was measured under full anesthesia at 6.95 m (22.8 ft), and somewhat less reliable scientific reports up to 10 m (33 ft) have appeared.[9]

Although weight is easier to measure reliably than length (e.g., by simply measuring the weight of a container with and without the snake inside it and subtracting one measurement from the other), a significant factor in the weight of a snake is whether it has been kept in captivity and provided an unusual abundance of food in conditions that also cause reduced levels of activity. Moreover, the weight of wild specimens is often reduced as a symptom of parasite infestations that are eliminated by veterinary care in captivity. Thus, the largest weights measured for captive specimens often greatly exceed the largest weights observed in the wild for the same species. This phenomenon may particularly affect the weight measurements for anaconda species that are especially difficult to keep in captivity due to their semi-aquatic nature, resulting in other species having larger weights measured in captivity. In particular, the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus) is an especially massive snake if only observations in the wild are considered.

Largest serpent species in the world

| Rank | Common name | Scientific name | Family | Mass | Image | Length | Range map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Green anaconda | Eunectes murinus | Boidae | May exceed 227 kg (500 lb),[10] validity questionable 97.5 kg (215 lb), reliable, maximum among 780 specimens caught over a seven-year period 1992–98[11] Average 30.8 kg (68 lb) among 45 specimens (1992–98)[11] Generally considered the heaviest in the wild (exceeded by P.bivittatus and M. reticulatus in captivity) |  | May exceed 8.8 m (28 ft 10 in),[10] not firmly verified[7] 6.27 m (20 ft 7 in), somewhat reliable[12] 5.6 m (18 ft 4 in), somewhat reliable[3] 5.21 m (17 ft 1 in), reliable, maximum among 780 specimens caught over a seven-year period 1992–98[11] Average 3.7 m (12 ft 2 in) among 45 specimens (1992–98)[11] Minimum adult length 3.2 m (10 ft 6 in)[3] |  |

| 2 | Burmese python | Python bivittatus (now recognized as distinct from P. molurus) | Pythonidae | 182.8 kg (403 lb), reliable, for "Baby" in 1998 (in captivity)[7] 98 kg (216 lb), reliable, for the heaviest individual in the wild[13][14][15][16] 94 kg (207 lb), reliable, for the biggest male in the wild[17][18][19] |  | 5.7912 m (19 ft 0 in), reliable, for the longest individual in the wild July 10, 2023 [20] [21] [22] Minimum adult length 2.35 m (7 ft 9 in)[3] |  |

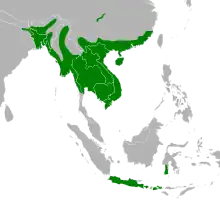

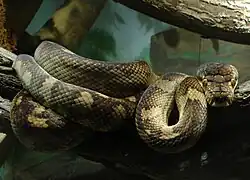

| 3 | Reticulated python | Malayopython reticulatus | Pythonidae | Up to 158 kg (350 lb), somewhat reliable[23][24] 158.8 kg (350 lb), somewhat reliable, for "Medusa" in 2011[25] About 156 kg (344 lb), somewhat reliable, for "Twinkie" in 2014[26][27] 136 kg (300 lb), somewhat reliable, for "Fluffy" in 2010[28] 133.7 kg (295 lb), reasonably reliable, for "Colossus" in 1954 (with an empty stomach)[7][29] 124.7 kg (275 lb), somewhat reliable, for "Samantha" in 2002[29][30] 115 kg (254 lb), somewhat reliable, for "Super Snake" in 2021[31][32][33] 59 kg (130 lb), reliable, wild specimen in 1999 (after not eating for nearly 3 months)[9] |  | 10 m (32 ft 10 in),[23][24] not firmly verified[7] 7.92 m (26 ft 0 in), somewhat reliable, for "Samantha" in 2002[29][30] 7.67 m (25 ft 2 in), somewhat reliable, for "Medusa" in 2011[25] 7.3 m (23 ft 11 in), somewhat reliable, for "Fluffy" in 2010[25][28] 7 m (23 ft 0 in), somewhat reliable, for "Twinkie" in 2014[27] 7 m (23 ft 0 in), somewhat reliable, for "Super Snake" in 2021[31][32][33] 6.95 m (22 ft 10 in), reliable, wild specimen in 1999[9] 6.35 m (20 ft 10 in), reasonably reliable, for "Colossus" in 1963 (skeletal length)[7] Minimum adult length 3.04 m (10 ft 0 in)[3] Generally considered the world's longest |

|

| 4 | Central African rock python | Python sebae (now recognized as distinct from P. natalensis) | Pythonidae | Up to 113 kg (250 lb),[34] not firmly verified[7] 91 kg (200 lb), reliable[35][36][37] |  | Up to 7.5 m (24 ft 7 in),[38] not firmly verified[7] 6.5 m (21 ft 4 in), reliable[39] Minimum adult length 2.50 m (8 ft 2 in)[3] |  Range shown as green region Range shown as green region |

| 5 | Southern African rock python | Python natalensis (now recognized as distinct from P. sebae) | Pythonidae | 80 kg (180 lb), somewhat reliable, for the largest specimen[40] 65 kg (143 lb), reliable[41] Of 75 individuals measured in South Africa, the longest female weighed 53.4 kg (118 lb).[42] |  | 6 m (19 ft 8 in)[43] not firmly verified 5.8 m (19 ft 0 in), reliable[39] Of 75 individuals measured in South Africa, the longest female was 4.34 meters long. Individuals longer than 4.6 meters are rare.[44] Typically 2.8–4 m (9 ft 2 in – 13 ft 1 in)[45] |  Range shown as orange region Range shown as orange region |

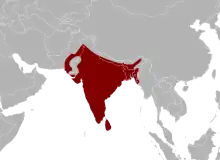

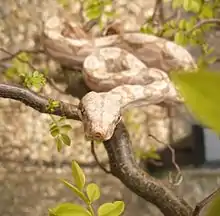

| 6 | Indian python | Python molurus (now recognized as distinct from P. bivittatus) | Pythonidae | 91 kg (200 lb),[46] not firmly verified[7] 52 kg (115 lb), reliable[47] |  | 6.4 m (21 ft 0 in),[46] not firmly verified[7] 4.6 m (15.1 ft), reliable[47] |  |

| 7 | Australian scrub python | Simalia kinghorni (now recognized as distinct from S. amethistina) | Pythonidae | 35 kg (77 lb),[48] reliable 24 kg (53 lb), reliable[49][50] | _Australia_Zoo.jpg.webp) | Some reports up to[51] or exceeding 8 m (26 ft 3 in),[3] not firmly verified[7] 7.2 m (23 ft 7 in),[52] not firmly verified[50] In excess of 6 m (19 ft 8 in)[51] 5.65 m (18 ft 6 in), reliable[49][50] Typically 3.5 m (11 ft 6 in)[3] Minimum adult length 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in)[3] Little information about size is available[3][53] |  Range shown as dark green region Range shown as dark green region |

| 8 | Amethystine python | Simalia amethistina (recently recognized as distinct from S. kinghorni) | Pythonidae | Able to reach 20 kg (44 lb),[54] and probably larger Little information about size is available[3][53] |  | Able to reach 5.5 m (18 ft 1 in)[54] 4.72 m (15 ft 6 in), reliable[55] Little information about size is available[3][53] |  Range shown as dark orange and bright orange regions Range shown as dark orange and bright orange regions |

| 9 | Yellow anaconda | Eunectes notaeus | Boidae | They commonly weigh 25–35 kg (55–77 lb), though large specimens can weigh 40–55 kg (88–121 lb) or even more.[56] |  | 4.6 m (15.1 ft), reasonably reliable[1][57] Typically 3–4 m (9 ft 10 in – 13 ft 1 in)[57] 3.1 m (10 ft 2 in) maximum among 86 specimens in a field study[58] | South America |

| 10 | Red tailed boa | Boa constrictor | Boidae | More than 45 kg (99 lb)[59] | .jpg.webp) | Possibly up to 4.3 m (14 ft 1 in)[60] A much larger report was debunked[7][61] |  [62] [62] |

| 11 | Cuban boa | Chilabothrus angulifer | Boidae | Maximum 40 kg (88 lb), reliable[63] 27 kg (60 lb), reliable[64] |  | 5.65 m (18 ft 6 in), for the largest specimen[63] Up to 4.8 m (15 ft 9 in)[64][65] | |

| 12 | Beni anaconda | Eunectes beniensis (now recognized as distinct from E. murinus and E. notaeus) | Boidae | 35 kg (77 lb) |  | Largest specimen 3.2 m (10 ft 6 in),[66] relatively reliable Typically up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in),[67][68] relatively reliable Little information about size is available (known from only six specimens as of 2009)[69] | |

| 13 | Dark-spotted anaconda | Eunectes deschauenseei (sometimes confused with E. notaeus) | Boidae | 30 kg (66 lb) | 3 m (9 ft 10 in),[70][71] relatively reliable |  | |

| 14 | Papuan python | Apodora papuana | Pythonidae | Average reported as 22.5 kg (50 lb)[72] Little information about size is available[3] |  | One reasonably reliable report of 4.39 m (14 ft 4.8 in)[3][73] Average reported as 4 m (13 ft 1.5 in)[72] Often reaches 3–4 m (9 ft 10.1 in – 13 ft 1.5 in)[3] Most specimens 1.4–3.6 m (4 ft 7 in – 11 ft 10 in)[73] Little information about size is available[3] | |

| 15 | Northern boa | Boa imperator (now recognized as distinct from B. constrictor) | Boidae | Can be over 20 kg (44 lb) |  Specimen from the Cayos Cochinos | Average adult length around 2 m (6 ft 7 in). Can reach up to 3.7 m (12 ft 2 in)[74] | .svg.png.webp) |

By families

Boas (Boidae)

- The most massive living member of this highly diverse reptilian order is the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus) of the neotropical riverways. These may exceed 8.8 m (29 ft) and 227 kg (500 lb), although such reports are not fully verified.[7] Rumors of larger anacondas also persist.[75] The reticulated python (Python reticulatus) of Southeast Asia is longer but more slender, and has been reported to measure as much as 10 m (33 ft) in length and to weigh up to 158 kg (348 lb).[52][24] The Burmese python, a south-east Asian species is known to weigh as much as 183 kg (403 lb) and is generally the heaviest snake among average modern wild specimens.

Typical Snakes (Colubridae)

- Among the colubrids, the most diverse snake family, the largest snakes may be the keeled rat snake (Ptyas carinata) at up to 4 m (13 ft).[76] The genus Drymarchon also contains some of the largest colubrids such as the eastern indigo snake (Drymarchon couperi) and the indigo snake (Drymarchon corais) which can both reach lengths of almost 3 m (9.8 ft).[77][78] The first one mentioned may grow to 5 kg (11 lb) and more.[77]

- Another large species in this family is the false water cobra (Hydrodynastes gigas) reaching a length of 3 m (9.8 ft), and a mass of 4.56 kg (10.1 lb),[79][80] one of the largest venomous snakes in South America. The tiger rat snake (Spilotes pullatus), also living in South America, can reach a length of 2.7 m (8 ft 10 in).[81] The yellow-bellied puffing snake (Pseustes sulphureus) can exceed a length of 3 m (9.8 ft).[82]

- The largest racer, the Hispaniola racer (Haitiophis anomalus), at an average length of 2 m (6 ft 7 in), is the longest snake species in the West Indies.[83]

Elapids (Elapidae)

- The longest venomous snake is the king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), with lengths (recorded in captivity) of up to 5.7 m (19 ft) and a weight of up to 12.7 kg (28 lb).[52] It is also the largest elapid. The second-longest venomous snake in the world is possibly the African black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis), which can grow up to 4.5 m (15 ft). Among the genus Naja, the longest member arguably may be the forest cobra (Naja melanoleuca), which can reportedly grow up to 3 m (9.8 ft). In the case of the Indian cobra (Naja naja), the majority of adult specimens range from 1 to 1.5 m (3 ft 3 in to 4 ft 11 in) in length. Some specimens, particularly those from Sri Lanka, may grow to lengths of 2.1 to 2.2 m (6 ft 11 in to 7 ft 3 in), but this is relatively uncommon.[84]

Blind Snakes (Leptotyphlopidae)

- The largest blind snake Giant blind snake (Rena maxima) is a female with a snout-to-vent length (SVL) of 33 cm (13 in) plus a tail 1.8 cm (0.71 in) long.[85]

Lamprophids (Lamprophiidae)

- The largest lamprophids Cape file snake (Heterolepsis capensis) is a medium to large snake. With an average total length (including tail) of about 120 cm (3 ft 11 in), specimens of 165 cm (5 ft 5 in) total length have been recorded. It has a very flat head, and its body is strikingly triangular in cross-section.

Vipers (Viperidae)

- The Gaboon viper (Bitis gabonica), a very bulky species with a maximum length of around 2 m (6 ft 7 in), is typically the heaviest non-constrictor snake and the biggest member of the viper family, with unverified specimens reported to as much as 20 kg (44 lb).[52][86] The wild verified largest specimen of 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) total length, caught in 1973, was found to have weighed 11.3 kg (25 lb) with an empty stomach.[52] And therefore, the heaviest venomous snake and also the largest species of viper in present usually is an eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) with a maximum reliable mass in 15.4 kg (34 lb) and maximum length of 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in).[87] While not quite as heavy, another member of the viper family is longer still, the South American bushmaster (Lachesis muta), with a maximum length of 3.65 m (12.0 ft).[88]

- The rattlesnake genus Crotalus, which includes the aforementioned eastern diamondback rattlesnake and western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox), reaches a maximum length of 2.13 m (7 ft 0 in), and according to W. A. King one large specimen had a length of 2.26 m (7 ft 5 in) and a mass of 11 kg (24 lb).[87] The third largest rattlesnake is the Mexican west coast rattlesnake (Crotalus basiliscus), which reaches 2.04 m (6 ft 8 in) long and 7.7 kg (17 lb) mass,[87] and one captive-raised male was weighed at 8.8 kg (19.4 lb) in 2020.[89]

Remarkable individual specimens

Individual specimens considered among largest measured for their respective species include the following:

- Burmese pythons:

- Wild caught (non-native invasive) Burmese python (Python bivittatus) female♀ 5.7912 m (19 ft 0 in) (19 ft) 56.699 kg (125.00 lb) caught in the Big Cypress National Preserve in eastern Collier County, Florida by Jake Waleri and Stephen Gauta on July 10, 2023. Waleri and several friends caught the large snake. They brought it to the Conservancy of Southwest Florida to have it officially documented. New current world record longest Burmese Python recorded by official measurement July 12, 2023 [90] [91] [92]

- "Baby" a captive Burmese python (Python bivittatus) female♀ 5.74 m (18 ft 10 in), 182.8 kg (403 lb); "Baby" was kept at Serpent Safari in Gurnee, Illinois, until its death at almost 27 years old, euthanized due to deteriorating condition caused by a tumor in 2006. Several live measurements and post mortem measurement.[7][93]

- "Hexxie" a captive Burmese python (Python bivittatus) female♀ 5.48 m (18.0 ft), 110 kg (240 lb) and still growing; "Hexxie" lives in a terraced house in Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, England, with owner Marcus Hobbs.[94][95][96]

- Wild-caught non-native (invasive) Burmese python (Python bivittatus) female♀ 5.39 m (17.7 ft), 98 kg (216 lb) and measured 64 cm (25 in) in diameter; She was carrying 122 developing eggs. Caught by a team of biologists in Everglades, Florida, June 22, 2022.[13][14][15][16]

- Wild-caught non-native (invasive) Burmese python (Python bivittatus) male♂ 5.23 m (17.2 ft), 94 kg (207 lb) and measured 66 cm (26 in) in diameter; caught by Okeechobee Veterinary Hospital, Florida, July 31, 2009.[17][18][19]

- Wild-caught non-native (invasive) Burmese python (Python bivittatus) female♀ 5.72 m (18.8 ft), 47.2 kg (104 lb); caught in Miami-Dade County, Florida, October 2, 2020.[97][98][99]

- Wild-caught non-native (invasive) Burmese python (Python bivittatus) female♀ 5.68 m (18.6 ft), 58.1 kg (128 lb); caught in Miami-Dade County, Florida, May 11, 2012. Intact specimen measured post mortem by University of Florida.[100][101][102]

- Wild-caught non-native (invasive) Burmese python (Python bivittatus) female♀ 5.56 m (18.2 ft), 60.3 kg (133 lb); caught by University of Florida wildlife biologist in Miami-Dade County, Florida, July 9, 2015. Intact specimen measured post mortem by University of Florida.[103][104][105][93]

- Wild-caught non-native (invasive) Burmese python (Python bivittatus) female♀ 4.57 m (15.0 ft), 65.3 kg (144 lb); caught by Nicholas Banos and Leonardo Sanchez, Everglades, Florida, April 1, 2017.[106][107][108][109]

- Wild-caught non-native (invasive) Burmese python (Python bivittatus) female♀ 5.2 m (17 ft), 63.5 kg (140 lb); she was carrying 73 developing eggs. Caught by Big Cypress National Preserve, Florida, April 7, 2019. [110][111][112]

- Reticulated pythons:

- "Medusa" a captive reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) female♀ 7.67 m (25.2 ft) 158.8 kg (350 lb); "Medusa" is kept at the Edge of Hell haunted house attraction in Kansas City, Missouri, and was last officially measured in 2011.[25][113]

- "Samantha" a captive (originally wild-caught near Samarinda, Borneo, as an already very large adult) reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) female♀ 7.92 m (26.0 ft), somewhat reliable in 2002[29][30]

- "Fluffy" a captive reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) female♀ 7.3 m (24 ft) 136 kg (300 lb); "Fluffy" was last officially measured live on September 30, 2009, and died at the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium in Powell, Ohio, on October 26, 2010, due to an apparent tumor. She was 18 years old. 24 feet confirmed when measured at death.[28][25]

- "Colossus", a captive reticulated python (Maylayopython reticulatus) male♂, skeletal measurement 6.35 m (20.8 ft) 133.7 kg (295 lb); "Colossus" was kept at the Highland Park Zoo in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, died in April 1963, and the body was deposited at the Carnegie Museum.[7]

- "Twinkie" a captive reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) female♀ 7 m (23 ft 0 in) 156 kg (344 lb); "Twinkie" found sanctuary in the 2014 Guinness World Records book as the world’s largest albino python in captivity. She was a fixture at The Reptile Zoo in Fountain Valley, CA.[26][27]

- "Super Snake", a captive reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) 14-year-old female♀ 7 m (23 ft), 115 kg (254 lb); "Super Snake" is kept at the National Aquarium in Al Qana, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.[31][32][33]

- Wild-caught reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) Female♀ 7.5 m (25 ft) adjusted post-mortem measurement, unreliable, originally measured alive at 8 m (26 ft) unreliably, using an unknown method, 250 kg (550 lb) – estimated weight upon capture, unreliable; caught April 7, 2016, Paya Terubong district, Penang Island, Malaysia. Died April 10, 2016.[114][115][116]

- Wild-caught reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) unknown sex 7.8 m (26 ft), unverified; Was killed on October 5, 2017, Pekanbaru, Indonesia.[117][118][119]

- Wild-caught reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) unknown sex 6 m (20 ft), 80 kg (180 lb); Probably, this is largest snake in Phuket in last decade. Caught by Ruamjai Rescue Foundation, December 18, 2014, Phuket, Thailand.[120][121][122]

- Australian scrub pythons:

- "Maximus" a captive scrub python (Simalia kinghorni) male♂ 5.1 m (17 ft), 25 kg (55 lb), at the peak weighed about 27 kg (60 lb), when he was last weighed and measured in 2008; "Maximus" is believed to be the largest Australian native snake in captivity. He is kept at the Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary on the Gold Coast, Queensland.[123][124]

- Wild-caught scrub python (Simalia kinghorni) unknown sex 5 m (16 ft), 28 kg (62 lb); caught by Machans Beach in Cairns, Queensland, November 14, 2017.[125][126]

- Wild-caught scrub python (Simalia kinghorni) unknown sex 5.1 m (17 ft), 27 kg (60 lb); caught by Speewah in Mareeba, Queensland, unknown date.[127]

- Wild-caught scrub pythons (Simalia kinghorni) unknown sex Both of were more 5 m (16 ft 5 in) (Second caught as stated measuring 5.1 m (16 ft 9 in) long and 27 kg (60 lb) in weight); caught by Speewah in Mareeba, Queensland, October 24, 2016.[128][129]

- Wild-caught scrub python (Simalia kinghorni) unknown sex 5.2 m (17 ft), 22 kg (49 lb); caught by Speewah in Mareeba, Queensland, February 6, 2017.[130][131][132]

See also

- List of largest reptiles

- List of largest extant lizards

- Largest organisms

- Titanoboa, world's largest known snake from the fossil record

- Gigantophis, one of the world's largest snakes (past record holder for the world's largest known snake from the fossil record)

References

- 1 2 Mehrtens, John (1987). Living Snakes of the World. New York: Sterling. ISBN 0-8069-6461-8.

- ↑ "ITIS - Report: Simalia oenpelliensis". www.itis.gov.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Murphy, J. C.; Henderson, R. W. (1997). Tales of Giant Snakes: A Historical Natural History of Anacondas and Pythons. Krieger Pub. Co. pp. 2, 19, 37, 42, 55–56. ISBN 0-89464-995-7.

- ↑ Rarest Python in the World. SnakeBytesTV. December 18, 2013. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ Breeding plan aims to save snakes. ABC News (Australia). March 29, 2012. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ Smith, Deborah (June 20, 2012). "Snakes alive – if only he'd been seeing double". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Barker, David G.; Barten, Stephen L.; Ehrsam, Jonas P.; Daddono, Louis (2012). "The Corrected Lengths of Two Well-known Giant Pythons and the Establishment of a new Maximum Length Record for Burmese Pythons, Python bivittatus" (PDF). Bull. Chicago Herp. Soc. 47 (1): 1–6. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ Gordon, David George, "The Search for the $50,000 Snake". MSN Encarta. Archived October 31, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Fredriksson, G. M. (2005). "Predation on Sun Bears by Reticulated Python in East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo". Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 53 (1): 165–168. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- 1 2 "Green anacondas: Eunectes murinus". National Geographic. September 10, 2010. Archived from the original on February 4, 2010. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- 1 2 3 4 Rivas, Jesús Antonio (2000). The life history of the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus), with emphasis on its reproductive Biology (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). University of Tennessee. pp. 7, 36 (esp. Table 3-1), 74–80 (esp. Table 5-1), 111. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ Wood, Gerald L. (1982). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats (3 ed.). London: Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 0-85112-235-3. The Guinness book of animal facts and feats at the Internet Archive.

- 1 2 "Florida nabs largest python ever found in state". Bbc.com. 23 June 2022. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- 1 2 "Portly python: heaviest-ever snake captured in Florida tips scales at 215lbs". Theguardian.com. 23 June 2022. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- 1 2 Dolasia, Kavi (27 June 2022). "Record-Breaking 215-Pound Burmese Python Captured In Florida". Dogonews.com. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- 1 2 "Florida's largest ever python has been found. Here's the untold story of its discovery". National Geographic. 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- 1 2 Morgan, Curtis (July 31, 2009). "Veterinarian Shoots 207-pound Python". Miami Herald. Retrieved 6 June 2022 – via Sun-Sentinel.

- 1 2 "200-pound python killed in Okeechobee". Archive.tcpalm.com. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- 1 2 "Southwest Florida Online News: 17 Foot Python Caught In Okeechobee". Swflorida.blogspot.com. 31 July 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ↑ https://www.npr.org/2023/07/13/1187497592/record-breaking-burmese-python-longest-florida

- ↑ "The longest Burmese python ever measured was caught in Florida this week: 'It was insane'". USA Today.

- ↑ https://www.miamiherald.com/news/state/florida/article277280358.html

- 1 2 Mexico, Todd (2000). "Python reticulatus". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- 1 2 3 "Reticulated python (Python reticulatus)". Cotswold Wildlife Park and Gardens. Retrieved 2018-12-31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Longest snake – ever (captivity)". Guinness Book of World Records. October 12, 2011. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- 1 2 "Twinkie The World's Largest Albino Reticulated Python Dies". Reptiles. August 14, 2014. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- 1 2 3 "This Twinkie is no dessert, but a Guinness World Record holder". Ocregister.com. 10 October 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- 1 2 3 "R.I.P. Fluffy: Guinness record-holding reticulated python, 24 feet long, dies at Columbus Zoo". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. October 27, 2010. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- 1 2 3 4 Murphy, John C. "The Reticulated Python, Malayopython, Clade". Giant Constricting Snakes: The Science of Large Serpents. JCM Natural History. Archived from the original on 2016-02-13. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- 1 2 3 Santora, Marc (November 22, 2002). "Never Leather, Samantha The Python Dies at the Zoo". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- 1 2 3 Rodrigues, Janice (September 7, 2021). "Abu Dhabi is now home to Super Snake, one of the largest reptiles in the world". The National News.

- 1 2 3 Fatima, Sakina (September 9, 2021). "World's largest snake from Los Angeles is now in Abu Dhabi". The Siasat Daily.

- 1 2 3 Buckeridge, Miles (September 8, 2021). "One of the world's largest snakes has a new home in Abu Dhabi". What's On.

- ↑ "African rock python". Oregon Zoo. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ Murphy, J. C., & Henderson, R. W. (1997). Tales of giant snakes: a historical natural history of anacondas and pythons. Florida: Krieger Publishing Company.

- ↑ Vincent, S. E.; Dang, P. D.; Herrel, A.; Kley, N. J. (2006). "Morphological integration and adaptation in the snake feeding system: a comparative phylogenetic study". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 19 (5): 1545–1554. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01126.x. PMID 16910984. S2CID 4662004.

- ↑ Bodson, L. (2003). A Python (" Python sebae" Gmelin) for the King: The Third Century BC Herpetological Expedition to Aithiopia (Diodorus of Sicily 3.36–37). Museum Helveticum, 60(1), 22-38.

- ↑ "African rock python (Python sebae)". Wildscreen. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- 1 2 W. R. Branch, W. D. Haacke: A Fatal Attack on a Young Boy by an African Rock Python Python sebae. Journal of Herpetology Vol.14, No.3, 1980, pp. 305–307.

- ↑ "Southern African Rock Python". Sabisabi.com. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ↑ "Southern African Python". African Snakebite Institute. 22 October 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ↑ G. J. Alexander: Thermal Biology of the Southern African Python (Python natalensis): Does temperature limit its distribution? In: R. W. Henderson, R. Powell (Hrsg.): Biology of the Boas and Pythons. Eagle Mountain Publishing Company, Eagle Mountain 2007, ISBN 978-0-9720154-3-1, pp. 51–75.

- ↑ "Python natalensis (South African python, Natal rock python)". Biodiversityexplorer.info. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ↑ F. W. FitzSimons: Pythons and their ways. George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd, London 1930, pp. 12, 17, 23, 32, 34, 39, 41, 67.

- ↑ p. Spawls, K Howell, R Drewes, J Ashe: A Field Guide to the Reptiles of East Africa. Academic Press, London 2002, ISBN 0-12-656470-1, pp. 305–310.

- 1 2 "Python molurus: Indian Python". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- 1 2 Minton, S. A. (1966), "A contribution to the herpetology of West Pakistan", Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 134 (2): 117–118, hdl:2246/1129.

- ↑ Natusch, Daniel; Lyons, Jessica; Mears, Lea-Ann; Shine, Richard (2020). "Biting off more than you can chew: attempted predation on a human by a giant snake (Simalia amethistina)" (PDF). Austral Ecology. Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University. 46 (1): 159–162. doi:10.1111/aec.12956. S2CID 225105592.

- 1 2 S. L. Fearn; J. Sambono (2000). "A reliable size record for the Scrub Python Morelia amethistina (Serpentes: Pythonidae) in north east Queensland". Herpetofauna. 30: 2–6. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- 1 2 3 Scanlon, John D. (2014). "3". Giant terrestrial reptilian carnivores of Cenozoic Australia. CSIRO Publishing.

- 1 2 Obst, Fritz Jürgen; Richter, Klaus; Jacob, Udo (1988). The Completely Illustrated Atlas of Reptiles and Amphibians for the Terrarium (originally published in German in 1984 as Lexicon der Terraristik und Herpetologie by Edition Leipzig). T.F.H. Publications. pp. 496–498. ISBN 978-0-86622-958-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- 1 2 3 Murphy, John C. "Amethystine Python, Simalia amethistina (Schneider)". Giant Constricting Snakes: The Science of Large Serpents. JCM Natural History. Archived from the original on 2016-02-13. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- 1 2 Natusch, Daniel; Lyons, Jessica; Shine, Richard (2022). "Spatial ecology, activity patterns, and habitat use by giant pythons (Simalia amethistina) in tropical Australia". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 5274. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.5274N. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-09369-5. PMC 8960824. PMID 35347214.

- ↑ Harvey, Michael B.; Barker, David G.; Ammerman, Loren K.; Chippindale, Paul T. (2000). "Systematics of Pythons of the Morelia amethistina Complex (Serpentes: Boidae) with the Description of three new Species". Herpetological Monographs. 14: 139–185. doi:10.2307/1467047. JSTOR 1467047.

- ↑ Mendez, M; Waller, T; Micucci, P; Alvarenga, E; Morales, JC (2007). "Genetic population structure of the yellow anaconda (Eunectes notaeus) in Northern Argentina: management implications". In Robert W. Henderson and Robert Powell. Biology of the Boas and Pythons (PDF). Eagle Mountain Publishing. pp. 405–415. ISBN 0972015434.

- 1 2 Colthorpe, Kelly (2009). "Eunectes notaeus". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ Murphy, John C. "Yellow Anaconda, Eunectes notaeus (Cope)". Giant Constricting Snakes: The Science of Large Serpents. JCM Natural History. Archived from the original on 2016-02-08. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ Boa Constrictor Fact Sheet – Woodland Park Zoo Seattle WA. Zoo.org. Retrieved on 2012-08-22.

- ↑ Wagner, D. "Boas". Barron's. ISBN 0-8120-9626-6

- ↑ Murphy, John C. "The Boa Clade". Giant Constricting Snakes: The Science of Large Serpents. JCM Natural History. Archived from the original on 2016-02-04. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ Card, Daren C.; Schield, Drew R.; Adams, Richard H.; Corbin, Andrew B.; Perry, Blair W.; Andrew, Audra L.; Pasquesi, Giulia I.M.; Smith, Eric N.; Jezkova, Tereza; Boback, Scott M.; Booth, Warren; Castoe, Todd A. (September 2016). "Phylogeographic and population genetic analyses reveal multiple species of Boa and independent origins of insular dwarfism" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 102: 104–116. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.05.034. PMC 5894333. PMID 27241629. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-02-03. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- 1 2 Rodríguez-Cabrera, Tomás M.; Morell Savall, Ernesto; Rodríguez-Machado, Sheila; Torres, Javier (2020). "Trophic Ecology of the Cuban Boa, Chilabothrus angulifer (Boidae)". IRCF Reptiles & Amphibians Conservation and Natural History. 27 (2): 169–200. doi:10.17161/randa.v27i2.14176. S2CID 237484442.

- 1 2 "Cuban boa". Attica Park Zoological Park. Retrieved 2018-12-31.

- ↑ "Cuban boa (Epicrates angulifer)". Wildscreen Arkive. Archived from the original on 2019-01-01. Retrieved 2018-12-31.

- ↑ "Beni Anaconda, Eunectes beniensis Dirksen". Giant Constricting Snakes – The Science of Large Serpents. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ↑ Yirka, Bob (5 May 2022). "Bolivian river dolphins observed playing with an anaconda". Phys.org.

- ↑ Entiauspe‐Neto, Omar M.; Reichle, Steffen; dos Rios, Alejandro (12 April 2022). "A case of playful interaction between Bolivian River Dolphins with a Beni Anaconda". Ecology. 103 (8): e3724. Bibcode:2022Ecol..103E3724E. doi:10.1002/ecy.3724. PMID 35412650. S2CID 248099710.

- ↑ Reed, Robert N.; Rodda, Gordon H. (2009). Giant constrictors: Biological and management profiles and an establishment risk assessment for nine large species of pythons, anacondas, and the boa constrictor. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2009-1202. Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. p. 217.

- ↑ Murphy, John C. "De Schauensee's Anaconda, Eunectes deschauenseei (Dunn and Conant)". Giant Constricting Snakes: The Science of Large Serpents. JCM Natural History. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ Dirksen, L.; Henderson, R. W. (2002). "Eunectes deschauenseei". Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. doi:10.15781/T2707WS99.

- 1 2 de Groot, Michael (2015). "Apodora Papuana: Papuan Olive Python". Pythonidae. Archived from the original on 2018-05-14. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- 1 2 Murphy, John C. "Papuan Olive Python, Simalia papuana (Peters and Doria, 1878)". Giant Constricting Snakes: The Science of Large Serpents. JCM Natural History. Archived from the original on 2016-02-13. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ "Common Boa Constrictor - Boa constrictor imperator". Exotic-pets.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- ↑ Green Anacondas, Green Anaconda Pictures, Green Anaconda Facts. Animals.nationalgeographic.com

- ↑ "Keeled Rat Snake - Ptyas carinata - Not Dangerous | Thailand Snakes". 20 January 2013.

- 1 2 Godwin, James C. Eastern Indigo Snake Fact Sheet. alaparc.org

- ↑ Lee, Julian C. 2000. A Field Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of the Maya World: the lowlands of Mexico, Northern Guatemala, and Belize. p. 286-287. 402 pp. ISBN 0-8014-8587-8 (paper).

- ↑ Loughman, Z. J. (2020). Utilization of Natural History Information in Evidence based Herpetoculture: A Proposed Protocol and Case Study with Hydrodynastes gigas (False Water Cobra). Animals, 10(11), 2021.

- ↑ Martinelli, I. M. (2011). 290 290 NATURAL HISTORY NOTES. Herpetological Review, 42, 2.

- ↑ "Spilotes pullatus". Reptile-database.reptarium.cz. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ Boos, Hans E.A. (2001). The Snakes of Trinidad and Tobago. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1-58544-116-3.

- ↑ Landestoy T., Miguel & Henderson, Robert & Rupp, Ernst & Marte, Cristian & Ortiz, Robert. (2013). Notes on the Natural History of the Hispaniolan Brown Racer, Haitiophis anomalus (Squamata: Dipsadidae), in the Southern Dominican Republic. IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS. 20. 130-139. Accessed at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284550279_Notes_on_the_Natural_History_of_the_Hispaniolan_Brown_Racer_Haitiophis_anomalus_Squamata_Dipsadidae_in_the_Southern_Dominican_Republic.

- ↑ Wüster, W. (1998). "The Cobras of the genus Naja in India" (PDF). Hamadryad. 23 (1): 15–32. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ↑ Santos-Bibiano, Rufino; Florentino Melchior, Laura I.; Beltrán-Sánchez, Elizabeth; Méndez-de la Cruz, Fausto R. (2016). "Rena maxima (Giant Blindsnake). Clutch size and maximum length". Mesoamerican Herpetology 3 (2): 503-504.

- ↑ Gaboon Viper, Bitis gabonica. California Academy of Sciences

- 1 2 3 Laurence M. Klauber (1972). Rattlesnakes: Their Habits, Life Histories, and Influence on Mankind. Vol. 1. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01775-7.

- ↑ Mehrtens JM. 1987. Living Snakes of the World in Color. New York: Sterling Publishers. ISBN 0-8069-6460-X.

- ↑ Monster Basiliscus Weighed – 20 lb Rattlesnake. SnakeBytesTV. April 1, 2020. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- ↑ https://www.npr.org/2023/07/13/1187497592/record-breaking-burmese-python-longest-florida

- ↑ "The longest Burmese python ever measured was caught in Florida this week: 'It was insane'". USA Today.

- ↑ https://www.miamiherald.com/news/state/florida/article277280358.html

- 1 2 Murphy, J. C.; Crutchfield, T. (2019). Giant Snakes: A Natural History. book services. pp. 32, 33. ISBN 978-1-64516-232-2.

- ↑ "Meet Hexxie - she could be the biggest Burmese python in the world and she lives in a terraced house in Tewkesbury". Gloucestershirelive.co.uk. 9 November 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ↑ "Are you living next door to the world's biggest Burmese python?". Itv.com. 12 November 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ↑ "Meet the dad who keeps world's biggest python inside his terraced Cotswolds home". Birminghammail.co.uk. 11 November 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ↑ Georgiou, Aristos (October 9, 2020). "Enormous Burmese python caught in Florida is largest ever found in state". Newsweek.

- ↑ "Hunters capture longest Burmese python ever caught in Florida". Miami Herald. October 8, 2020 – via Tampa Bay Times.

- ↑ "Massive 18-foot python wraps around hunter during capture in Florida Everglades". Fox13news.com. 9 October 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ "National Geographic Society Newsroom". Archived from the original on 2021-04-25. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ↑ "18-foot-8-inch python caught in South Florida". Associated Press. May 20, 2013. Archived from the original on 2021-04-25. Retrieved 2021-04-25 – via The Florida Times-Union.

- ↑ "Record-setting python killed by knife-wielding Miami man". Tampa Bay Times. May 20, 2013.

- ↑ Staletovich, Jenny (July 30, 2015). "Near-record python bagged at Everglades National Park". Miami Herald. Retrieved 2021-11-30.

- ↑ Berenson, Tessa (July 30, 2015). "This 18-Foot Python Was Captured in the Florida Everglades". Time. Retrieved 2021-12-01.

- ↑ "18-Foot Python Captured in Florida Everglades". NBC News. July 29, 2015.

- ↑ "144-pound, 15-foot python captured by Florida snake hunters". Daytondailynews.com. April 5, 2017. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- ↑ "Python hunters capture 15-foot snake in Florida Everglades". Foxnews.com. April 4, 2017. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- ↑ "Snake fan hunts pythons in Florida to save other critters". Providencejournal.com. May 5, 2017. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- ↑ "Python hunters take on Florida Everglades' snake problem". Cbsnews.com. May 17, 2017. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- ↑ Mettler, K. "A 17-foot, 140-pound python was captured in a Florida park. Officials say it's a record". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ↑ Agius, Ritianne (April 8, 2019). "Record 5.2 metre-long Python caught in Florida – it carried 73 eggs". Tvmnews.mt. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ↑ "Record 5.2m-long python caught in Florida carrying 73 eggs". Nine.com.au. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ↑ Meier, Travis (October 17, 2019). "Medusa, the world record-holding python, celebrates 15th birthday at KC's 'The Edge of Hell'". Fox 4 News WDAF-TV.

- ↑ Geggel, Laura (April 12, 2016). "World's Longest Snake Dies 3 Days After Being Captured". Live Science.

- ↑ "'Longest-ever' captured python dies in Malaysia". BBC News. April 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Giant python found on Malaysian building site". Phys.org. April 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Giant python: Indonesians eat huge snake after man defeats reptile". BBC News. 5 October 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ↑ "Villagers Defeated 7.8 Metre Python, Then Whole Village Ate The Snake". Ndtv.com. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ↑ "Giant python: Indonesians eat huge snake after man defeats reptile". Steemit.com. 9 October 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ↑ "Phuket finds biggest python in 10 yrs". Bangkok Post. Phuket News. December 19, 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ↑ "Monster Phuket python caught, decade record set". Thethaiger.com. Legacy Phuket Gazette. December 18, 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ↑ "Monster Phuket Python Caught, A Six Metre Record". Huahintoday.com. December 27, 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ↑ "Python Maximus stretches out to 5.1 metres". ABC News. 29 March 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ↑ "Country's biggest snake Maximum loses weight". Adelaidenow.com.au. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ↑ "Big Scrub Python – Machans Beach". Cairnssnakecatcher.com.au. 24 August 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ "Pythons running a-fowl of residents by raiding chicken". Cairnspost.com.au. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ↑ "5.5m Scrub Python in Speewah". Cairnssnakecatcher.com.au. 20 August 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ "Two monster scrub pythons caught in Speewah near Cairns in two days". Cairnssnakecatcher.com.au. 27 October 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ "Two monster scrub pythons caught in Speewah near Cairns in two days". The Cairns Post. 23 October 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ↑ "Huge scrub python tries its luck at 'duck buffet' on Queensland property". Au.news.yahoo.com. 29 March 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ↑ George-Allen, Sam (21 November 2017). "Wet QLD Weather Means Snakes Are Keen To Move Into Your House (Yes, Yours)". Pedestrian.tv. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ↑ "Big Python Vs Hot Chocolate…(the duck)". Cairnssnakecatcher.com.au. 20 August 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2022.