| Kullervo | |

|---|---|

| Symphonic work by Jean Sibelius | |

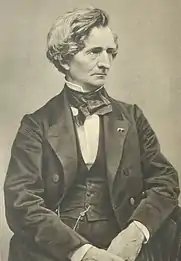

The composer (c. 1891) | |

| Opus | 7 |

| Text | Kalevala (Runos XXXV–VI) |

| Language | Finnish |

| Composed | 1891–1892 (withdrawn 1893) |

| Publisher | Breitkopf & Härtel (1966)[1] |

| Duration | 73 mins.[2] |

| Movements | 5 |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 28 April 1892[3] |

| Location | Helsinki, Grand Duchy of Finland |

| Conductor | Jean Sibelius |

| Performers |

|

Kullervo (sometimes referred to as the Kullervo Symphony), Op. 7, is a five-movement symphonic work for soprano,[lower-alpha 1] baritone, male choir, and orchestra written from 1891–1892 by the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius. Movements I, II, and IV are instrumental, whereas III and V feature sung text from Runos XXXV–VI of the Kalevala, Finland's national epic. The piece tells the story of the tragic hero Kullervo, with each movement depicting an episode from his ill-fated life: first, an introduction that establishes the psychology of the titular character; second, a haunting "lullaby with variations" that portrays his unhappy childhood; third, a dramatic dialogue between soloists and chorus in which the hero unknowingly seduces his long-lost sister; fourth, a lively scherzo in which Kullervo seeks redemption on the battlefield; and fifth, a funereal choral finale in which he returns to the spot of his incestuous crime and, guilt-ridden, takes his life by falling on his sword.[lower-alpha 2]

The piece premiered on 28 April 1892 in Helsinki with Sibelius conducting the Helsinki Orchestral Association and an amateur choir; the baritone Abraham Ojanperä and the mezzo-soprano Emmy Achté sang the parts of Kullervo and his sister, respectively. The premiere was a resounding success—indeed, the definitive breakthrough of Sibelius's nascent career and the moment at which orchestral music became his chosen medium. The critics praised the confidence and inventiveness of his writing and heralded Kullervo as the dawn of art music that was distinctly Finnish. Sibelius's triumph, however, was due in part to extra-musical considerations: by setting the Finnish-language Kalevala and evoking—but not directly quoting—the melody and rhythm of Finnic rune singing, he had given voice to the political struggle for Finland's independence from Imperial Russia.

After four additional performances—and increasingly tepid reviews—Sibelius withdrew Kullervo in March 1893, saying he wanted to revise it. He never did, and as his idiom evolved beyond national romanticism, he suppressed the work. (However, individual movements were played a few times during his lifetime, most notably the third on 1 March 1935 for the Kalevala's centenary.) Kullervo would not receive its next complete performance until 12 June 1958, nine months after Sibelius's death, when his son-in-law Jussi Jalas resurrected it for a recorded, private concert in Helsinki.

Kullervo eschews obvious categorization, in part because of Sibelius's indecision. At the premiere, program and score each listed the piece as a symphonic poem; nevertheless, Sibelius referred to Kullervo as a symphony both while composing the piece and again in retirement when reflecting on his career. Today, many commentators prefer to view Kullervo as a choral symphony, due to its deployment of sonata form in the first movement, its thematic unity, and the presence of recurring material across movements. Such a perspective conceptualizes Kullervo as Sibelius's "Symphony No. 0" and thereby expands his completed contributions to the symphonic canon from seven to eight.

Kullervo has been recorded many times, with Paavo Berglund and the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra having made the world premiere studio recording in 1970. A typical performance lasts about 73 minutes,[2] making it the longest composition in Sibelius's œuvre.

History

Premiere

Preparations for a work as massive as Sibelius's Kullervo stretched Helsinki's musical resources to the limit: the copyists labored to write out the parts,[6] while organizers hired extra musicians because the Helsinki Orchestral Association then consisted of just thirty-eight permanent members.[7] Moreover, the city had no professional chorus, and so about forty amateur vocalists were cobbled together from the University Chorus and the Helsinki Parish Clerk and Organ School's student choir.[7] The rehearsals were also a challenge: the musicians, the majority of whom were Germans, not only viewed Sibelius as a neophyte but also had little understanding of the national heritage upon which Kullervo drew—a few of them even laughed derisively when they saw their parts[8] and when the soloists sang.[9] Speaking a mix of Finnish, Swedish, and German as needed, Sibelius gradually won over his performers through the force of his personality;[8] as one vocalist recalled, "We doubted that we could learn our parts ... [but] the young composer himself would come and hold special rehearsals with us. This raised our self-esteem. And he came. His eyes were ablaze! It was that inspirational fire of which the poets speak".[6]

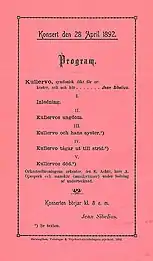

Kullervo premiered on 28 April 1892 at a sold-out concert audience in the Ceremonial Hall of the Imperial Alexander's University of Finland, Sibelius—initially pale and trembling—conducting. The soloists were the Finnish mezzo-soprano Emmy Achté and baritone Abraham Ojanperä.[8] The audience—a mix of the regular concert-going public and patriots there for the nationalist spectacle[8]—received two leaflets: first, a Swedish-language program that described Kullervo as a "symphonic poem" ("symfonisk dikt"); and second, text in Finnish, (with a Swedish translation) from The Kalevala for Movements III and V, as well as a motto that helped it to contextualize the instrumental Movement IV.[10] Notably, this was the first time in history that a concert audience had been given a Finnish-language text.[11] Although the orchestra overpowered Ojanperä and Achté,[8] the performance was a success: enthusiastic applause erupted after each movement and, at the end, Kajanus presented Sibelius with a blue-and-white-ribboned laurel wreath that quoted prophetically lines 615–616 of Runo L of The Kalevala: "That way now will run the future / On the new course, cleared and ready".[12] The next day, Kullervo received its second performance—again under Sibelius's baton—at a matinée concert, and on 30 April, Kajanus conducted the fourth movement at a popular concert that concluded the season.[13][9][lower-alpha 3]

Withdrawal and partial suppression

Following the 1892 concerts, Sibelius married Aino on 10 June at the Järnefelt summer home in Tottesund, Vöyri (Vörå),[lower-alpha 4] the success of Kullervo having convinced Aino's parents (and Sibelius's mother) that he would be able to provide for their daughter.[14][15] To satisfy Sibelius's "longing for the wilds",[16] the couple honeymooned in the Karelian village of Lieksa on Lake Pielinen. (Later, Sibelius claimed that this was when he first met Paraske.)[17] Around this time, Sibelius mailed the autograph manuscript of Kullervo to his friend, the Swedish playwright Adolf Paul, in Vienna; they had hoped to interest the Austrian conductor Felix Weingartner in the piece, but nothing came of the plan.[18] On 6, 8, and 12 March 1893, the Orchestral Society again performed Kullervo under Sibelius's baton,[19] with Ojanperä and Achté reprising their roles. Critics received these concerts coolly, faulting the work for its excessive length, jarring dissonances, and inexpert orchestration.[20] Afterwards, Sibelius withdrew Kullervo, saying he wanted to revise it. He did not do so, and as the years ticked by, he focused on other projects, placing Kullervo aside.[lower-alpha 5] In 1905, Kajanus borrowed the score for a 5 February performance of Movement IV at a patriotic concert celebrating Runeberg Day.[9][lower-alpha 6]

In 1915, Sibelius wrote to Kajanus asking that he return the autograph manuscript of Kullervo, which was then the only copy. The impetus for this request was two-fold. First, the composer and scholar Erik Furuhjelm had begun writing a Swedish-language biography in honor of Sibelius's semicentennial; to continue the book, he needed to examine the work that had launched Sibelius's career.[22] Second, an 15 August article about Kajanus in Hufvudstadsbladet had listed a 'Kullervo' among his compositions; having likely forgotten that Kajanus indeed had written a piece called Kullervo's Funeral March in 1880, a paranoid Sibelius "jumped to the conclusion" that Kajanus had appropriated Kullervo as his own.[23][lower-alpha 7] Stunningly, Kajanus had mislaid the score following the 1905 concert, and a "nerve-wracking" hunt ensued. When searches of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra and Music Institute libraries proved unsuccessful,[22] a "wholly mystif[ied]" Kajanus began to worry that "some crazy manuscript collector [might] have purloined the score".[23] His patience exhausted, Sibelius in his diary entertained the possibility of conspiracy: "Letter from [Kajanus]. He has not taken the slightest care of Kullervo or—this is more likely—one of the orchestral staff who belongs to the clique around him has burnt it".[22] In December, Kajanus located the manuscript in his personal library.[22] Around 1916, Sibelius deposited the manuscript in Helsinki University Library for safekeeping, only to sell it to the Kalevala Society in the early 1920s in order to address his dire financial situation.[31][32][33]

A decade later, Cecil Gray, Sibelius's first English-language biographer and an advocate in Britain for his music, reported that Sibelius had told him Kullervo would likely remain unrevised:

He confesses to being not entirely satisfied with the work as it stands, and while admitting that he might conceivably be able to remedy the more outstanding defects by rewriting it here and there he is nevertheless disinclined to do so, being of the opinion that the faults and imperfections of a work are often so intimately bound up with its very nature, that an attempt to rectify them without impairing it as a whole must almost inevitably fail ... The only really satisfactory method of re-writing a work is to recast it from beginning to end, and Sibelius no doubt feels that he is more profitably engaged in writing new works than in re-writing old ones ... The chances are, then, that Kullervo will never see the light of day.[34]

Nevertheless, in early 1935, as Finland prepared to celebrate the centenary of the Kalevala's publication, Armas Väisänen—the ethnomusicologist and general secretary of the festival—secured Sibelius's blessing to have Kullervo's third movement performed under the baton of Georg Schnéevoigt. (Väisänen had taken Schnéevoigt to the Helsinki University Library to examine the autograph manuscript; the conductor did not find Kullervo to be on par with Sibelius's mature works, and was only willing to conduct Movement III.)[31] The concert was held on 1 March at the newly-built Messuhalli,[9] which was "filled to the brim".[31] The performers were the Helsinki Philharmonic and a choir drawn from the YL Male Voice Choir and Laulu-Miehet,[35] with the tenor Väinö Sola (who substituted when the baritone Oiva Soini took ill before the dress rehearsal)[31] and the lyric soprano Aino Vuorjoki serving as soloists.[35][lower-alpha 8] In a review for Helsingin Sanomat, Evert Katila wrote that, given the caustic receives Kullervo received in 1893, Movement III "surprised and astonished with its clarity, simplicity and subtle beauty". However, he faulted the soloists as woefully unsuitable in terms of timbre and dramatic interpretation: "[they] did not do full justice to the composition".[35]

The final time that any movement of Kullervo was performed during Sibelius's lifetime was in 1955 on the composer's ninetieth birthday, when Ole Edgren conducted the Turku Philharmonic Orchestra in Movement IV.[9] However, in the spring of 1957, just months before his death, Sibelius arranged for bass and orchestra the baritone's concluding monologue—Kullervo's Lament (Kullervon valitus)—from Movement III.[lower-alpha 9] By this time Sibelius's hand tremor had become so severe that he could not himself write down the notes; instead, he dictated the orchestration to his son-in-law Jussi Jalas. The impetus for returning to Kullervo had been a request by the Finnish bass-baritone Kim Borg for a song from Sibelius. Borg premiered Kullervo's Lament on 14 June in Helsinki during Sibelius Week, Jalas conducting the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra.[37]

Posthumous revival

Sibelius died on 20 September 1957. Nine months later, on 12 June 1958, Kullervo received its first complete performance of the twentieth century at a private concert in University Hall,[38] which the Finnish government had organized in honor of the King of Denmark Frederik IX's state visit;[39] the Finnish president Urho Kekkonen was also present. Jalas conducted the Philharmonic Orchestra and Laulu-Miehet, with the baritone Matti Lehtinen and soprano Liisa Linko-Malmio as soloists.[39] The concert was recorded—a first for Kullervo—and a copy was gifted to the Danish king. The next day, as part of Sibelius Week, Jalas repeated Kullervo for a public concert held at Messuhalli.[38] Writing in Helsingin Sanomat, Martti Vuorenjuuri described Kullervo as "an astonishing leap away from all music that preceded it" with "themes [that] are rather successful, sometimes even ingenious"; nevertheless, he faulted Sibelius for a "scattered ... architecture" and predicted that, while excerpts from Kullervo would be suitable for the concert repertoire, the piece "in its entirety will not become living art".[39][lower-alpha 10]

Two additional productions of Kullervo are also of historical significance. First, the world premiere of Kullervo outside of Finland was on 19 November 1970 in Bournemouth, England, with Paavo Berglund conducting the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra and the YL Male Voice Choir; the soloists were the baritone Usko Viitanen and mezzo-soprano Raili Kostia.[40] The next day, Berglund repeated Kullervo at Royal Festival Hall in London.[40] Writing for The Times, William Mann praised Kullervo as "dramatically gripping", with "choral writing [... that] is stern and monolithic, often powerful, and ... eloquent solos for brother and sister"; he also described Sibelius as "a gifted musical experimenter, with as strong a sense of design as of thematic character".[40] In The Guardian, Edward Greenfield characterized Kullervo as a work of "striking originality" and "Mahlerian scale".[41] Second, on 10 March 1979, Kullervo received its American premiere at Uihlein Hall in Milwaukee, with Kenneth Schermerhorn conducting the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra and the Wisconsin Conservatory Symphony Chorus; the baritone Vern Shinall and mezzo-soprano Mignon Dunn were the soloists. In a review for The Milwaukee Journal, Roxane Orgill faulted Sibelius as a "longwinded conversationalist" and dismissed Kullervo as having "wander[ed] aimlessly ... it could be argued that the score should never have been dusted off".[42] On 13 April, Schermerhorn's crew (albeit with the West Minster Men's Choir substituting) played Kullervo at Carnegie Hall in New York. In The New York Times, Raymond Ericson found Kullervo "verbose and very uneven. Yet ... it has the unique Sibelius sound, starkly colorful, darkly sonorous ... and the melodic lines have a flavorsome folklike tinge that makes them quite beautiful".[43]

Initially, there was some debate as to the propriety of performing a work that Sibelius withdrew, did not revise, and left unpublished. Santeri Levas, Sibelius's private secretary from 1938–1957, wrote that the Jalas concert was "against the expressed wish of the recently deceased master".[44] Evidence in support of this perspective is that Sibelius regularly denied performance requests. For example, when on 31 August 1950 Olin Downes—the music critic for The New York Times and Sibelius 'apostle'—wrote to the composer to secure Kullervo's American premiere, Sibelius refused in a 5 September response. "I still feel deeply for this youthful work of mine", Sibelius explained. "Perhaps that accounts for the fact that I would not like to have it performed abroad during an era that seems to me so very remote from the spirit that Kullervo represents ... I am not certain that the modern public would be able to place it in its proper perspective ... even in my own country I have declined to have it produced".[45][lower-alpha 11] However, Erik Tawaststjerna, Sibelius's most expansive biographer, argued that the posthumous revival of Kullervo "was certainly not in conflict with [Sibelius's] last wishes", as before his death he "reconciled to the idea that the symphony in its entirety might be taken up ... and finally accepted it as something quite natural".[14]

Instrumentation

Kullervo is scored for soprano,[lower-alpha 1] baritone, male choir (tenors and baritones), and orchestra. The choir sings in Movements III and V, while the soloists appear in III only. The orchestra includes the following instruments:[47]

- Woodwinds: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, cor anglais, 2 clarinets (in A and B♭), bass clarinet (in B♭), and 2 bassoons

- Brass: 4 horns (in D, E, and F), 3–4 trumpets (in D, E, and F), 3 trombones, and tuba

- Percussion: timpani, triangle, and cymbals

- Strings: violins, violas, cellos, and double basses

Sibelius did not publish Kullervo in his lifetime, and for many decades the score existed only in the autograph original. From 1932–1933, as Finland prepared for the Kalevala's 1935 jubilee, Sibelius had the score copied—for his personal use—by the violinist Viktor Halonen.[33] After the composer's death, Breitkopf & Härtel obtained the rights to Kullervo in 1961 and published Halonen's copy (with emendations) five years later.[48][lower-alpha 12] A critical edition of Kullervo, edited by the musicologist Glenda Dawn Goss, arrived in 2005; her work is based on the autograph manuscript, as well as the original orchestral and choral parts (preserved at the Sibelius Museum in Turku) and piano-vocal arrangements of Movements III and V that Sibelius used for rehearsals (preserved at the National Library of Finland in Helsinki, to which his estate transferred in the 1980s).[49]

Structure

Each of the five movements present a part of Kullervo's life, based on the Kullervo cycle from the Kalevala. Movements one, two, and four are instrumental. The third and fifth contain sung dialogue from the epic poem. The work runs over an hour. Some recent recordings range from 70 to 80 minutes.

- 1. Introduction [Allegro Moderato]

This movement evokes the heroic sweep of the legendary Finnish setting, as well as the character Kullervo, a complex, tragic figure.

- 2. Kullervo's Youth [Grave]

This movement reflects the sombre tone of Runos 31 through 33 of the Kalevala. Kullervo is marked for tragedy from birth, and spends his youth largely in slavery.

- 3. Kullervo And His Sister [Allegro Vivace]

The baritone and mezzo-soprano represent the protagonist and his sister, while the male chorus set the scene and offer commentary. Kullervo encounters three women and unsuccessfully attempts to seduce them, before succeeding with the third, only to realise too late that she is his long-lost sister. When she learns the truth, she leaps into a stream and drowns. Kullervo laments his crime and his sister's death.

- 4. Kullervo Goes To Battle [Alla Marcia]

Kullervo attempts to atone for his crime by seeking death on the battlefield.

- 5. Kullervo's Death [Andante]

An haunting male chorus recount Kullervo's death. He inadvertently comes to the site where he raped his sister, marked by dead grass and bare Earth where nature refuses to renew itself. He addresses his sword, asking if it is willing to drink guilty blood. The sword answers, and Kullervo falls on his sword.

Analysis

Recategorizing Kullervo as a symphony

Sibelius went on to become one of the most important symphonists of the early twentieth century: his seven numbered symphonies, written between 1899 (the Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39) and 1924 (the Symphony No. 7 in C major, Op. 105), are the core of his oeuvre and stalwarts of the concert repertoire. However, the standard cycle is predated by two projects that Sibelius, during the compositional process, referred to as "symphonies". First, in 1891, Sibelius wrote the Overture in E major (JS 145) and Scène de ballet (JS 163), which he had intended as the initial two movements of a symphony before abandoning his plan.[50][51] Second, in 1891 and early 1892, Sibelius continually labeled Kullervo a "symphony" ("symfoni") in letters to Aino Järnefelt, Kajanus, and Wegelius,[52] before settling on "symphonic poem" ("symfonisk dikt") for the April premiere—a title that newspaper advertisements[lower-alpha 13] and program shared. Sibelius likely "shrank" from the former classification due both to Kullervo's programmatic nature, as well as its deployment of a hybrid structure in which a "quasi-operatic ... scena" essentially 'interrupts' an up-to-that-point 'normal' work for orchestra.[53]

Nevertheless, in retirement while reflecting on his career, Sibelius returned to describing Kullervo as a symphony.[54] For instance, in 1945 the City of Loviisa requested Sibelius's blessing for a plaque in his honor that included in its description "[here] Jean Sibelius composed his Kullervo Suite". On 27 February, Sibelius sent the following correction: "Kullervo symphony (not suite)" (emphasis and underlining in the original).[52] Presumably, had he still considered the work a symphonic poem, he could have written so. Also, later in life, Sibelius conceded that in fact he had written nine symphonies, Kullervo and the Lemminkäinen Suite (Op. 22) inclusive.[55][56]

The symphonic poem appellation has struck many commentators as ill-fitting; an early example is that, after examining the score in 1915, Furuhjelm re-conceptualized Kullervo as an "epic drama" in two acts (Movements III and V), with two preludes (I and II) and an intermezzo (IV).[57] More commonly, however, scholars have categorized Kullervo as a choral symphony, a descendant of Beethoven's Ninth (1824), Berlioz's Roméo et Juliette (1839), and Liszt's Dante (1856) and Faust (1857), as well as a contemporary of Mahler's Resurrection Symphony (1894).[58] This perspective emphasizes the internal cohesion of the work and its faithfulness to, rather than deviation from, established symphonic practice.[52][59] As Tawaststjerna has argued:

The three purely orchestral movements ... follow traditional patterns: sonata-form, rondo and scherzo, while in the two choral movements ... Sibelius writes freely in a durchkomponiert manner as did, say, Lizst in the Dante Symphony. The coexistence of these two formal structures serves to give the work some of its inner tension and its contrast ... Sibelius succeeds in holding these diverse elements together remarkably well: in the finale he recalls themes from earlier movements and so effectively completes the symphonic cycle. Another source of strength is the unit of the thematic substance itself: the main ideas seem to belong to one another.[54]

Similarly, Layton's verdict is that although in Kullervo Sibelius "embraces concepts that, strictly speaking, lie outside the range of the normal classical symphony"—such as Movement III—he does so "without sacrificing [the] essentially organic modes of procedure" that characterize the symphonic process.[53] Goss concurs, writing in the preface to Kullervo's complete edition, "The composer's numerous and unequivocal remarks about the music as well as its specific structural features ... leave little doubt that Kullervo is not just Sibelius's first major symphonic work: it is his first symphony",[52] or as Breitkopf & Härtel have since advertised it, a de facto "Symphony No. 0".

Discography

.jpg.webp)

The Finnish conductor Paavo Berglund and the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra made the world premiere studio recording in 1970 (1971 release; U.S. distributor: Angel Records SB-3778; U.K. distributor: His Master's Voice SLS 807/2). In an effort to "gain balance" between soloists and orchestra, Berglund—on the "valuable" advice of Jalas—made alterations to the score, correcting what he had perceived to be Sibelius's "impractical orchestration" and "some passages [that were] clumsy or even impossible to play". In Movement III, for example, Berglund swapped out the original orchestration of Kullervo's Lament for Sibelius's 1957 reorchestration, albeit transposed to the original key. Writing for The Musical Times, Hugh Ottaway applauded the recording for its "strong sense of occasion", noting "Berglund's enthusiasm has brought a brilliant, dedicated performance ... [that] could well be a revelation. It is a triumph for all concerned".[60] In 1985, Berglund—now with the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra—recorded Kullervo for a second time.

As of February 2021, Kullervo has been recorded twenty times, the most recent of which dates to August 2018 and is by the Finnish conductor Hannu Lintu and the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra. In terms of superlatives, two other Finnish conductors, Leif Segerstam and Osmo Vänskä, as well as Britain's Sir Colin Davis, have since joined Berglund as having recorded the symphony twice. Among vocalists, the Finnish baritone Jorma Hynninen and the Finnish soprano Johanna Rusanen have sung the roles of Kullervo and Kullervo's sister, respectively, four times; and at six performances, the YL Male Voice Choir holds the record among choirs. Finally, the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, and the London Symphony Orchestra jointly hold orchestra record, at two performances each.

The sortable table below lists all twenty commercially available recordings of Kullervo:

Notes, references, and sources

Notes

- 1 2 3 Although Kullervo is scored for a soprano soloist in Movement III, many performances—including the 1892 premiere—instead utilize a mezzo-soprano.

- ↑ The Kalevala is a collection of folk poetry compiled by Elias Lönnrot. In the original version from 1835 (the Old Kalevala), all of Kullervo's story but his childhood enslavement (then in Runo XIX) is absent. Only with the epic's expansion in 1849, did Lönnrot—who between editions had visited the Karelian isthmus and Ingria and heard many oral poems about Kullervo—enlarge the Kullervo narrative and place it into its own cycle (Runos XXXI–VI).[4][5]

- ↑ Also on Robert Kajanus's 30 April 1892 program were compositions by, among others, Armas Järnefelt (Lyrical Overture, 1892), the conductor (Finnish Rhapsody No. 1, 1881), Fredrick Pacius (Vårt land, 1848), and Martin Wegelius (Daniel Hjort Overture, 1872).

- ↑ This article uses the Finnish name for municipalities in Finland; the Swedish name provided parenthetically.

- ↑ Sibelius's had not definitively given up on Kullervo, as his diary from January 1910 lists Movements II, IV, and V under the title 'Old Pieces to be Rewritten'.[21]

- ↑ Kajanus's 5 February 1905 program also included Sibelius's The Swan of Tuonela (Op. 22/2) and Finlandia (Op. 26). The other composers represented were Järnefelt (Korsholma, 1894), the conductor (his orchestration of the Porilaisten marssi by C. F. Kress), Erkki Melartin (the ballet music from The Sleeping Beauty [Prinsessa Ruusunen], 1904; Siikajoki, 1903), and Selim Palmgren (the Waltz from the Cinderella Suite [Tuhkimo-sarja], 1903).

- ↑ Sibelius was the third composer to write music based on Kullervo's story, although each of its predecessors involved the "uneasy marriage of Central European Romanticism to Finnish topics" rather than the development of a genuinely national musical idiom.[24] First, in 1860, Filip von Schantz wrote the Kullervo Overture (Kullervo-alkusoitto), which he had intended as the prelude to an opera; this piece premiered the same year in Helsinki at the opening of the Swedish Theatre.[25] Second, in 1880, Robert Kajanus composed and premiered in Leipzig Kullervo's Funeral March (Kullervon surumarssi); though Wagnerian in its chromaticism, it makes use of the Finnish folk song O Mother, so pitiable and poor! (Voi äiti parka ja raukka!).[26] Additionally, two other Kullervo compositions appeared during Sibelius's lifetime:[27] in 1913, Leevi Madetoja composed and premiered his symphonic poem Kullervo;[28] and in 1917, Armas Launis wrote and premiered his opera Kullervo.[29][30] Neither man—born in 1887 and 1884, respectively—could have known Sibelius's Kullervo, as he had withdrawn it in 1893.

- ↑ Georg Schnéevoigt's 1 March 1935 program also included movements from Sibelius's Lemminkäinen Suite (Op. 22), then in its partially-published state: The Swan of Tuonela (published in 1900) and, as manuscripts from 1896, Lemminkäinen and the Maidens of the Island and Lemminkäinen in Tuonela, which had not been heard since 1897. The other composers represented were Yrjö Kilpinen (six orchestral songs sung by Hanna Granfelt), Uuno Klami (three movements from the Kalevala Suite, 1933), and Melartin (A Wedding in Pohjola [Pohjolan häät], 1902).

- ↑ In 1892–93, Sibelius arranged Kullervo's Lament for voice and piano, translated into German (Kullervos Wehruf); due to the differences between Finnish and German, he made alterations to the metre of the vocal line. Later in 1917–18, Sibelius used the 1890s German arrangement to make new one in Finnish for voice and piano, changing the metre back to the original. This arrangement was printed in the music magazine Säveletär.[36]

- ↑ The Jussi Jalas recording is available courtesy of the Finnish Broadcasting Company, although it is unclear whether this is from 12 June or 13 June.

- ↑ Sibelius did, however, consent to Downes's 4 October request to have a facsimile of the manuscript mailed to New York, so that he could study Kullervo for a book he was writing on the topic of the composer's development. (Preemptively, he had pledged to keep Kullervo "in the most sacred confidence ... I would promise never to show it to a single conductor or musician ... [and] I would never in any article quote a theme".) In a letter from 9 November, Downes described the anticipated copy as the "most precious gift that I [will] have ever received in music".[46]

- ↑ Halonen "like every human copyist ... inevitably introduced his share of mistakes ... and he repeated, rather than corrected, most of the composer's [original] errors". The poor state of the score, Goss argues, explains why, even after Sibelius's death, performances of Kullervo remained rare—except in Finland, where "Finnish conductors ... had access to Sibelius's autograph manuscript and the initiative to create their own parts".[48]

- ↑ The newspapers are Päivälehti (in Finnish, headline 'Konsertin'), Hufvudstadsbladet (in Swedish, headline 'Konsert'), and Nya Pressen (in Swedish, 'Konsert').

- ↑ Refers to the year in which the performers recorded the work; this may not be the same as the year in which the recording was first released to the general public.

- ↑ P. Berglund–EMI (5 74200 2) 2000

- ↑ P. Berglund–EMI (5 65080 2) 1994

- ↑ N. Järvi–BIS (CD–313) 1986

- ↑ E. Salonen–Sony (SK 52 563) 1993

- ↑ L. Segerstam–Chandos (CHAN 9393) 1995

- 1 2 3 This orchestra records under its in-house label.

- ↑ E. Klas–Sibelius Academy (SACD–7) 1996

- ↑ J. Saraste–Finlandia (0630–14906–2) 1996

- ↑ J. Panula–Naxos (8.553756) 1996

- ↑ C. Davis–RCA (82876–55706–2) 2003

- ↑ P. Järvi–Virgin (7243 5 45292 2 1) 1997

- ↑ O. Vänskä–BIS (CD–1215) 2001

- ↑ C. Davis–LSO Live (LSO0074) 200?

- ↑ A. Rasilainen–cpo (777 196–2) 2006

- ↑ R. Spano–Telarc (CD–80665) 2006

- ↑ L. Segerstam–Ondine (ODE 1122–5) 2008

- ↑ L. Botstein–ASO (ASO217) 2011

- ↑ S. Oramo–BBC Music (BBC MM413) 2017

- ↑ O. Vänskä–BIS (SACD–2236) 2020

- ↑ T. Dausgaard–Hyperion (CDA68248) 2019

- ↑ H. Lintu–Ondine (ODE 1338–5) 2019

References

- ↑ Dahlström 2003, p. 24.

- 1 2 Dahlström 2003, pp. 21–23.

- ↑ Dahlström 2003, p. 23.

- ↑ Goss 2003, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Magoun, Jr. 1963, p. 362.

- 1 2 Barnett 2000, p. 3.

- 1 2 Barnett 2007, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tawaststjerna 2008a, p. 106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barnett 2000, p. 4.

- ↑ Goss 2005, pp. xiv, xvii.

- ↑ Goss 2005, p. xiv.

- ↑ Goss 2005, pp. xv, xvii–xviii.

- ↑ Tawaststjerna 2008a, p. 120.

- 1 2 Tawaststjerna 2008a, p. 121.

- ↑ Barnett 2007, p. 75.

- ↑ Ekman (1938), p. 115.

- ↑ Tawaststjerna 2008a, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Tawaststjerna 2008a, p. 166.

- ↑ Barnett 2007, p. 80.

- ↑ Goss 2005, p. xv.

- ↑ Tawaststjerna 2008b, pp. 43–44.

- 1 2 3 4 Tawaststjerna 2008b, pp. 63–64.

- 1 2 Barnett 2007, p. 253.

- ↑ Korhonen 2007, p. 38.

- ↑ Goss 2003, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Goss 2003, p. 55.

- ↑ Goss 2003, p. 72.

- ↑ Korhonen 2007, p. 50.

- ↑ Korhonen 2007, p. 58.

- ↑ Barnett 2007, p. 291.

- 1 2 3 4 Väisänen 1958, p. 15.

- ↑ Murtomäki 1993, p. 3.

- 1 2 Goss 2007, p. 22.

- ↑ Gray 1934, pp. 69–70.

- 1 2 3 Katila 1935, p. 7.

- ↑ Barnett 2007, pp. 279, 405, 408.

- ↑ Barnett 2007, p. 348.

- 1 2 Barnett 2000, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Vuorenjuuri 1958, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 Mann 1970, p. 11.

- ↑ Greenfield 1970, p. 7.

- ↑ Orgill 1979, p. 34.

- ↑ Ericson 1979, p. 35.

- ↑ Levas 1986, p. xiii.

- ↑ Goss 1995, pp. 218–220.

- ↑ Goss 1995, pp. 221–225.

- ↑ Goss 2005, p. ii.

- 1 2 Goss 2007, p. 24.

- ↑ Goss 2007, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Barnett 2007, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Tawaststjerna 2008a, pp. 88–93.

- 1 2 3 4 Goss 2005, p. xi.

- 1 2 Layton 1996, p. 6.

- 1 2 Tawaststjerna 2008a, p. 107.

- ↑ Tawaststjerna 2008a, p. 177.

- ↑ Hurwitz 2007, p. 46.

- ↑ Johnson 1959, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Hurwitz 2007, p. 45–47, 50.

- ↑ Rickards 1997, p. 48.

- ↑ Ottaway 1971, p. 975.

Sources

- Books

- Barnett, Andrew (2007). Sibelius. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300163971.

- Brockway, Wallace; Weinstock, Herbert (1958) [1939]. "XXII: Jean Sibelius". Men of Music (Revised and Enlarged ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 574–593. ISBN 0671465104.

- Downes, Olin (1956). Sibelius the Symphonist. New York: The Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York. OCLC 6836790.

- Ekman, Karl [in Finnish] (1938) [1935]. Jean Sibelius: His Life and Personality. Translated by Birse, Edward. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. OCLC 896231.

- Dahlström, Fabian [in Swedish] (2003). Jean Sibelius: Thematisch-bibliographisches Verzeichnis seiner Werke [Jean Sibelius: A Thematic Bibliographic Index of His Works] (in German). Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel. ISBN 3-7651-0333-0.

- Goss, Glenda Dawn (1995). Jean Sibelius and Olin Downes: Music, Friendship, Criticism. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 9781555532000.

- Goss, Glenda Dawn, ed. (2005). "Preface". Kullervo. (Urtext from the Complete Edition of Jean Sibelius Works, Series I – Orchestral Works, Volume 1.1–3). Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel. p. xi–xviii. ISMN 9790004211809. PB 5304.

- Gray, Cecil (1934) [1931]. Sibelius (2nd ed.). London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 373927.

- Hurwitz, David (2007). Sibelius: The Orchestral Works—An Owner's Manual. (Unlocking the Masters Series, No. 12). Pompton Plains, New Jersey: Amadeus Press. ISBN 9781574671490.

- Johnson, Harold (1959). Jean Sibelius (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. OCLC 603128.

- Kirby, William Forsell, ed. (1907). The Kalevala: Or the Land of Heroes. Vol. 2. London: J. M. Dent & Co. OCLC 4130641.

- Korhonen, Kimmo [in Finnish] (2007) [2003]. Inventing Finnish Music: Contemporary Composers from Medieval to Modern. Translated by Mäntyjärvi, Jaakko [in Finnish] (2nd ed.). Jyväskylä, Finland: Finnish Music Information Center (FIMIC) & Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy. ISBN 9789525076615.

- Levas, Santeri (1986) [1972]. Jean Sibelius: A Personal Portrait. Translated by Young, Percy (2nd ed.). Porvoo and Juva, Finland: Werner Söderström oy. ISBN 9789510136089.

- Magoun, Jr., Francis Peabody, ed. (1963). The Kalevala: Or Poems of the Kaleva District. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674500105.

- Rickards, Guy (1997). Jean Sibelius. (20th-century Composers Series). London: Phaidon. ISBN 9780714835815.

- Ringbom, Nils-Eric [in Finnish] (1954) [1948]. Jean Sibelius: A Master and His Work. Translated by de Courcy, G. I. C. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma. ISBN 9780837198408.

- Tawaststjerna, Erik (2008a) [1965/1967; trans. 1976]. Sibelius: Volume I, 1865–1905. Translated by Layton, Robert. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 9780571247721.

- Tawaststjerna, Erik (2008b) [1978/1988; trans. 1997]. Sibelius: Volume III, 1914–1957. Translated by Layton, Robert. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 9780571247745.

- Journals and magazines

- Goss, Glenda Dawn (2003). "A Backdrop for Young Sibelius: The Intellectual Genesis of the Kullervo Symphony". 19th-Century Music. University of California Press. 27 (1): 48–73. JSTOR 10.1525/ncm.2003.27.1.48.

- Goss, Glenda Dawn (2007). "Jean Sibelius's Choral Symphony Kullervo". The Choral Journal. American Choral Directors Association. 47 (8): 16–26. JSTOR 23557207.

- Ottaway, Hugh (1971). "Reviewed Work(s): Kullervo; Scene with Cranes; Swanwhite (excerpts)". The Musical Times. Musical Times Publications Ltd. 112 (1544): 975. JSTOR 955066.

- Newspapers

- Ericson, Raymond (15 April 1979). "Milwaukee in Program of Sibelius". The New York Times. No. 44, 188. p. 35. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- Greenfield, Edward (21 November 1970). "Sibelius Premiere at the Festival Hall". The Guardian. p. 7. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- Katila, Evert [in Finnish] (3 March 1935). "Kalevalan 100-vuotismuisto: Arvokkaita juhlatilaisuuksia Helsingissä ja maaseudulla" [The 100th Anniversary of the Kalevala: Expensive Celebrations in Helsinki and the Countryside]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). No. 59. p. 7. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Mann, William (23 November 1970). "Sibelius: Festival Hall". The Times. No. 58030. p. 11. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- Orgill, Roxanne (11 March 1979). "Sibelius Epic Not Very Gripping". The Milwaukee Journal. p. 34. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- Väisänen, Armas (13 June 1958). "Lisä Kullervo-sinfonian esitysvaiheisiin" [An Additional Note on the Performances of the Kullervo Symphony]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). No. 157. p. 15. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- Vuorenjuuri, Martti [in Finnish] (13 June 1958). "Kullervo-sinfonia kuninkaan kunniaksi" [Kullervo Symphony in Honor of the King]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). No. 157. p. 14. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- Liner notes

- Barnett, Andrew (2000). Kullervo (PDF) (CD booklet). Osmo Vänskä & Lahti Symphony Orchestra. BIS. p. 3–7. CD–1215. OCLC 1116152375

- Layton, Robert (1996). Kullervo (CD booklet). Jukka-Pekka Saraste & Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra. Finlandia. p. 4–7. 0630–14906–2. OCLC 658830103

- Murtomäki, Veijo [in Finnish] (1993). Kullervo (CD booklet). Esa-Pekka Salonen & Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. Sony Classical. p. 3–6. SK 52563. OCLC 36229109

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)