| Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. | |

|---|---|

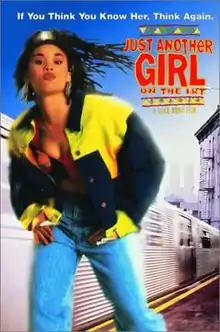

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Leslie Harris |

| Written by | Leslie Harris |

| Produced by | Leslie Harris Irwin Wilson |

| Starring | Ariyan A. Johnson Kevin Thigpen Ebony Jerido |

| Cinematography | Richard Conners |

| Edited by | Jack Haigis |

| Music by | Eric Sadler |

Production company | Truth 24 F.P.S |

| Distributed by | Miramax Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $130,000 |

| Box office | $479,169 |

Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. is a 1992 American drama film written, produced, and directed by Leslie Harris. The film follows Chantel, a Black teenager living in the New York City projects. The film addresses a variety of contemporary social and political issues including teenage pregnancy, abortion, racism, poverty, and HIV/AIDS. Just Another Girl on the I.R.T is Harris' first and only feature film to date. The film premiered at the 1992 Toronto International Film Festival and later screened at the 1993 Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Special Jury Prize. Ariyan A. Johnson earned an Independent Spirit Award nomination for Best Actress.[1]

The "I.R.T." in the film's title refers to the IRT Lexington Avenue Line of the New York City Subway system.

Plot

Chantel Mitchell is a 17-year-old African-American high school junior who lives in Brooklyn, New York. Chantel is very smart, but her sharp tongue, abundant ego, and occasional naivete undermine her efforts to achieve her ultimate dream: to leave her poor neighborhood, go to college, and eventually become a doctor. Throughout the film, Chantel breaks the fourth wall and explains that she wants to be seen as more than just another teenage black girl on the subway.

She lives with her struggling working-class parents and her two younger brothers. With her mother at work during the day and her father working the night shift (and thus, sleeping all day), Chantel is given the responsibility of taking care of her brothers, in addition to going to school full-time and working a part-time job at a local grocery store. Despite this, she earns mostly As and Bs in school, and is fully determined to receive an education beyond her primary one. Much to the chagrin of her teachers, she wants to graduate early, in order to get into college as soon as possible. Her dream is tested by her constant clashes with her school's administration, along with her romantic involvement with her seemingly rich boyfriend Tyrone. Lacking a proper sex education, Chantel ends up pregnant and must contend with her future.

Cast

- Ariyan A. Johnson as Chantel Mitchell

- Kevin Thigpen as Tyrone

- Ebony Jerido as Natete

- Chequita Jackson as Paula

- Jerard Washington as Gerard

- Tony Wilkes as Owen Mitchell

- Karen Robinson as Debra Mitchell

- Johnny Roses as Mr. Weinberg

- Kisha Richardson as Lavonica

- Monet Cherise Dunham as Denisha

- Wendell Moore as Mr. Moore

- William Badgett as Cedric

Production

Development

The idea for the film generated from a short film Leslie Harris made for Planned Parenthood titled “Another Girl”,[2] as well as a personal experience Harris had as a teenager when her friend became pregnant. "And we were actually, like, the kind of smart kids at school. It really profoundly affected me when I found out she was pregnant—just how it changed her life, the whole responsibility of it," said Harris.[3]

Harris knew she wanted to make a film that centered on a Black woman, explaining she "was just tired of seeing the way black women were depicted, as wives or mothers or girlfriends or appendages. All from the point of view of male directors. [In I.R.T., Chantel's] the central character. There's no male character to validate her."[4] Because Harris "wanted to avoid the clichéd drug obsession accompanying male violence of most 'street' films," she ran into resistance from potential producers and financiers.[5] She said "I knew I always wanted to do a feature-length film...but for a woman… I really wasn’t encouraged. People feel that a woman can’t handle a feature-length. I was told, ‘Hey, why don’t you make it into a documentary?’"[5] At that time, the only prior feature-length film to be directed by a Black woman and get theatrical distribution was 1991's Daughters of the Dust by Julie Dash.[3][5]

Of her film's central character, Harris said "I wanted a 17-year-old, and from a creative stand point, I wanted to avoid delineating bad girl or good girl. It’s as if you can’t have a central character who’s not good at all, and from my experience I think people are a combination of bad and good.”[5] Harris also chose to shoot the film in a cinéma-vérité style, giving the audience "the feeling that you’re experiencing this girl’s life along with her. I wanted to have the film very bright, not dark and bleak, just a difference in perspective of how life goes on.”[5]

Ariyan A. Johnson was cast in the role of Chantel from over 200 hopefuls.[2]

Filming

The film was shot entirely in New York City. With a budget of only $130,000,[6] the entire film was reportedly shot in just 17 days.[7] Funds came from grants through organizations such as the American Film Institute, the National Endowment for the Arts, and Women Make Movies.[4][3] Author Terry McMillan and filmmaker Michael Moore helped to finance the post-production when it was running low on funding.[5]

Release

The film first screened at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 17, 1992.[1] It went on to screen at the 1993 Sundance Film Festival to acclaim, winning the Special Jury Prize for Outstanding First Feature for director Leslie Harris and securing distribution with Miramax.[8][6] The Miramax deal made I.R.T. the first film directed by a Black woman to get wide-release distribution.[6] The film opened in select cities on February 26, 1993,[4] expanding to a wide release on March 19.[1] The film grossed $479,169[9] on a budget of $130,000[6]

Critical reception

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 67% of 49 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 6/10.[10]

Positive reviews praised Ariyan Johnson's performance as Chantel, with Hal Hinson of The Washington Post stating she "seizes the camera's attention like no other performer since John Travolta strutted into Saturday Night Fever."[11] Though some critics described the film as "awkwardly staged"[12] and said the second half loses its footing,[13] many agreed the film was groundbreaking for featuring the perspective of a teenage girl, in comparison to other Black coming-of-age films like Boyz n the Hood, Juice, and Straight Out of Brooklyn.[14]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone wrote "Harris offers an adrenalin rush of energy and talent. Her artfully stylized, explosively funny film also manages to be deeply moving without jerking easy tears", and that Harris represents "a bracing new voice; she keeps her big little movie brimming with the pleasures of the unexpected."[15] Marjorie Baumgarten of The Austin Chronicle wrote Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. is "a faithful portrait of teenage emotional life" and "ultimately offers a welcome glimpse of one of the individuals behind the sea of faces racing by in the subway cars -- the kind of face and individual that Hollywood customarily has never given a second look."[16]

Legacy

Since its release, Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. has been praised as a pioneering film about Black Americans, in particular a film directed by a Black woman, and is regularly screened at film festivals.[17][3] Jim McKay's 2000 film Our Song, a coming-of-age film starring Kerry Washington, was inspired by I.R.T.[3] Writer Tyler Young has argued the film "open[ed] the door" for films such as Crooklyn, Akeelah and the Bee, and The Hate U Give.[18] In 2020, a retrospective article in The New Yorker, stated the film captures the complex social pressures facing a Black teenage girl and argued filmmakers have "dared not do another film like it."[19]

Leslie Harris has spoken of the difficulty of producing any further feature-length films despite positive reviews of her directorial debut. Her career has drawn comparisons to other Black women directors such as Julie Dash, who similarly premiered a film at Sundance but struggled to green-light future projects. According to Harris, despite the success of Black directors such as Spike Lee and John Singleton, the film industry has been hostile to Black women, and she could not arrange funding for any other projects.[6][20]

On the 30th anniversary of the film's premiere at Sundance, Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. was given a digital restoration in 4K and was shown on the 2022 Sundance Film Festival's digital platform.[8]

Home media

Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. was released on VHS in October 1993 and on DVD on May 21, 2002.[21] In September 2021, it was featured as part of the "New York Stories" streaming lineup with 62 other films on The Criterion Channel.[22]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. - Notes". Turner Classic Movie Database. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- 1 2 Peters, Ida (April 3, 1993). "Just Another Girl on the I.R.T." Baltimore Afro-American. pp. B5. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Keogan, Natalia (May 27, 2022). ""Have I Mentioned I'm Working on a Sequel?" Leslie Harris on Her Groundbreaking 1993 Film Just Another Girl on the I.R.T." Filmmaker Magazine. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- 1 2 3 Weinraub, Bernard (January 26, 1993). "A Trip Straight Out of Brooklyn To the Sundance Film Festival". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Coleman, Beth (1993). "Leslie Harris' Just Another Girl on the I.R.T - Filmmaker Magazine - Winter 1993". Filmmaker Magazine. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marshell, Kyla (July 12, 2018). "Leslie Harris: 'You just can't get a film financed with a black woman lead'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. (1993)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2007.

- 1 2 ""Just Another Girl on the I.R.T." Is This Year's From the Collection Film". sundance.org. January 26, 2022. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. (1992)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Just Another Girl on the I.R.T." Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on March 23, 2008. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ↑ Hinson, Hal (April 2, 1993). "Just Another Girl on the I.R.T." The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Just Another Girl on the I.R.T." Variety. December 31, 1991. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ Ryan, Desmond (April 2, 1993). "New Director's Story Of A Spirited Girl In The 'hood". Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ Steinmetz, Johanna (April 2, 1993). "'Irt' Focuses On The Girls In The 'hood". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ Travers, Peter (March 19, 1993). "Just Another Girl on the I.R.T." Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 18, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Baumgarten, Marjorie (April 16, 1993). "Movie Review: Just Another Girl On the I.R.T." The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ Castillo, Monica (November 16, 2018). "From 'Jinn' To 'Just Another Girl On The I.R.T.': Black Girlhood On Film". NPR. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Young, Tyler (August 27, 2018). "The Lasting Appeal of 'Just Another Girl on the I.R.T.'". Shondaland. Archived from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ↑ Brody, Richard (January 24, 2020). "The Still Astonishing "Just Another Girl on the I.R.T."". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ↑ "25 Years Later: Catching Up With Just Another Girl On The I.R.T Director Leslie Harris". blackfilm.com. March 14, 2018. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. (1993) - Releases". AllMovie. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Yakas, Ben (September 9, 2021). "Criterion Channel Launches Ultimate "63-Film Salute" To New York City". Gothamist. Retrieved September 18, 2022.