The city of Beijing has a long and rich history that dates back over 3,000 years.[11][12]

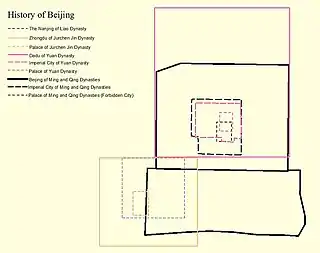

Prior to the unification of China by the First Emperor in 221 BC, Beijing had been for centuries the capital of the ancient states of Ji and Yan. It was a provincial center in the earliest unified empires of China, Qin and Han. The northern border of ancient China ran close to the present city of Beijing, and northern nomadic tribes frequently broke in from across the border. Thus, the area that was to become Beijing emerged as an important strategic and a local political centre.[13] During the first millennia of imperial rule, Beijing was a provincial city in northern China. Its stature grew in the 10th to the 13th centuries when the nomadic Khitan and forest-dwelling Jurchen peoples from beyond the Great Wall expanded southward and made the city a capital of their dynasties, the Liao and Jin. When Kublai Khan made Dadu the capital of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), all of China was ruled from Beijing for the first time. From 1279 onward, with the exception of two interludes from 1368 to 1420 and 1928 to 1949, Beijing would remain as China's capital, serving as the seat of power for the Ming dynasty (1421–1644), the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1644–1912), the early Republic of China (1912–1928) and now the People's Republic of China (1949–present).

Prehistory

The earliest remains of hominid habitation in Beijing Municipality were found in the caves of Dragon Bone Hill near the village of Zhoukoudian in Fangshan District, where the Homo erectus Peking Man (previously classified as the now-invalid species Sinanthropus pekinensis) lived from 770,000 to 230,000 years ago.[14] Paleolithic homo sapiens also lived in the caves from about 27,000 to 10,000 years ago.[15]

In 1996, over 2,000 Stone Age tools and bone fragments were discovered at a construction site at Wangfujing in the heart of downtown Beijing in Dongcheng District.[16] The artifacts date to 24,000 to 25,000 years ago and are preserved in the Wangfujing Paleolithic Museum in the lower level of the New Oriental Plaza mall.

Archaeologists have discovered over 40 neolithic settlements and burial sites throughout the municipality. The most notable include Zhuannian of Huairou District; Donghulin of Mentougou District; Shangzhai and Beiniantou of Pinggu District; Zhenjiangying of Fangshan; and Xueshan of Changping District.[17][18] These sites indicate that farming was widespread in the area 6,000 to 7,000 years ago. Painted pottery and carved jade of the Shangzhai and Xueshan Cultures resemble those of the Hongshan Culture further to the north.[19]

Pre-imperial history

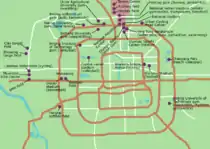

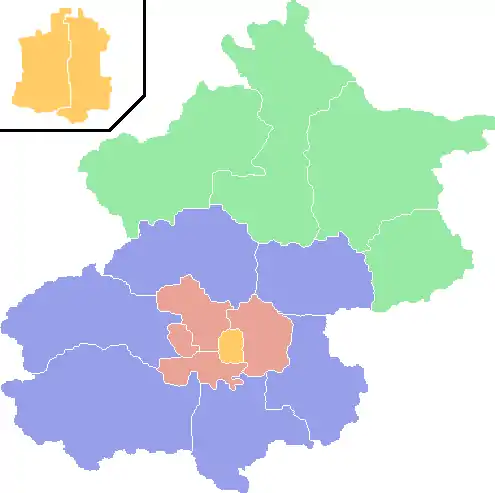

| The Districts and Counties of Beijing Municipality |

|---|

|

|

The earliest events of Beijing's history are shrouded in legend and myth. The epic Battle of Banquan, which according to Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian, occurred in the 26th century BC, may have taken place near the Upper and Lower Banquan Villages of Yanqing County on the northwestern edge of Beijing Municipality.[20][Note 17] The triumph of the Yellow Emperor over the Yan Emperor at Banquan united the two Emperors' tribes and gave rise to the Huaxia or Chinese nation, which then defeated Chiyou and the Nine Li tribes in the Battle of Zhuolu, possibly at Zhuolu, 75 km (47 mi) west of Yanqing in Hebei Province.[20][21] This victory opened North China to settlement by the descendants of the Yan and Yellow Emperors.

The Yellow Emperor is said to have founded the settlement of Youling (幽陵) in or near Zhuolu.[21] The sage-king Yao founded a town called Youdu (幽都) in the Hebei-Beijing region about 4,000 years ago.[21] You (幽) or Youzhou (幽州) later became one of the historical names for Beijing. Yuzishan, in Shandongzhuang Village of Pinggu County, in the northeastern fringe of Beijing Municipality, is one of several places in China claiming to host the Yellow Emperor's Tomb.[Note 18] Yuzishan's association with Yellow Emperor dates back at least 1,300 years when Tang poets Chen Zi'ang and Li Bai mentioned the tomb in their poems about Youzhou.[22]

The first event in Beijing's history with archaeological support dates to the 11th century BC when the Zhou dynasty absorbed the Shang dynasty. According to Sima Qian, King Wu of Zhou, in the 11th year of his reign, deposed the last Shang king and conferred titles to nobles within his domain including the rulers of the city states Ji (薊) and Yan (燕).[23] According to Confucius, King Wu of Zhou was so eager to establish his legitimacy that before dismounting his chariot, he named the descendants of the Yellow Emperor as the rulers of Ji.[24] He then named his kinsman, Shi, the Duke of Shao, as the vassal of Yan. Shi was preoccupied with other matters and dispatched his eldest son to take the position. This son, Ke, is considered the founder of the state of Yan. Bronzeware inscriptions have confirmed these events described in Sima Qian's history. Although the dates in Sima Qian's history before 841 BC have not yet been definitely matched to the Gregorian Calendar, the Beijing Government uses 1045 BC as the official estimate of the date of this occasion.[25]

It is believed that the seat of Ji, called the City of Ji or Jicheng (薊城), was located in the southwestern part of present-day urban Beijing, just south of Guang'anmen in Xicheng and Fengtai Districts.[26] Several historical accounts mention a "Hill of Ji" northwest of the city, which would correspond to the large mound at the White Cloud Abbey outside Xibianmen, about 4 km (2.5 mi) north of Guang'anmen.[Note 19] South and west of Guang'anmen, roof tiles used for palace construction and dense concentrations of wells lined with ceramic ring tiles have been discovered.[26]

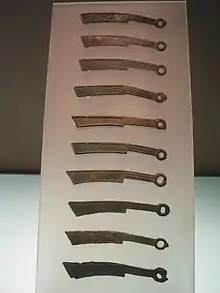

The capital of Yan was located about 45 km (28 mi) to the south of Ji, in the village of Dongjialin in Liulihe Township of Fangshan District, where a large walled settlement and over 200 tombs of nobility have been unearthed.[27] Among the most significant artifacts from the Liulihe Site is the three-legged bronze Jin Ding whose inscriptions recount the journey of Jin, who was sent by Ji Ke to deliver a batch of food and drink to his father, Ji Shi, in the Zhou capital.[28] The father was thrilled and awarded Jin cowry shells to pay for the creation of an honorific ding to remember the event. The inscription thus confirms the appointment of King Zhou's kin to Yan and the location of Yan's capital.

Both Yan and Ji were situated along an important north–south trade route along the eastern flank of the Taihang Mountains from the Central Plain to the northern steppes. Ji, located just north of the Yongding River, was a convenient rest stop for trade caravans. Here, the route to the northwest through the mountain passes diverged from the road to the Northeast. Ji also had a steady water supply from the nearby Lotus Pool, which still exists south of the Beijing West railway station. The Liulihe settlement relied on the more seasonal flow of the Liuli River. Some time during the Western Zhou or early Eastern Zhou dynasty, Yan conquered Ji and moved its capital to Ji, which continued to be called Jicheng or the City of Ji until the 2nd century AD.[26] Due to its historical association with the State of Yan, the city of Beijing is also known as Yanjing (燕京) or the "Yan Capital."[Note 20]

The State of Yan continued to expand until it became one of the seven major powers during the Warring States period (473–221 BC).[32] It stretched from the Yellow River to the Yalu.[Note 21] Like subsequent rulers of Beijing, the Yan also faced the threat of invasions by the Shanrong steppe nomads, and built walled fortifications across its northern frontier. Remnants of the Yan walls in Changping County date to 283 BC.[33] They predate Beijing's better known Ming Great Wall by more than 1,500 years.

In 226 BC, the City of Ji fell to the invading State of Qin and the State of Yan was forced to move its capital to Liaodong.[34] The Qin eventually ended Yan in 222 BC. The following year, the ruler of Qin, having conquered all the other states, declared himself to be the First Emperor.

Early imperial history

During the first one thousand years of Chinese imperial history, Beijing was a provincial city on the northern periphery of China proper. Dynasties with capitals in the Central and Guanzhong Plains used the city to manage trade and military relations with nomadic peoples of the north and northeast.[35]

The Qin dynasty built a highly centralized state and divided the country into 48 commanderies (jun), two of which are located in present-day Beijing. The City of Ji became the seat of Guangyang Commandery (广阳郡/廣陽郡). To the north, in present-day Miyun County, was Yuyang Commandery. The Qin removed defensive barriers dividing the Warring States, including the southern wall of the Yan, which separated the Beijing Plain from the Central Plain, and built a national roadway network.[35] Ji served as the junction for the roads connecting the Central Plain with Mongolia and Manchuria.[35] The First Emperor visited Ji in 215 BC and, to protect the frontier from the Xiongnu, had the Great Wall built in Yuyang Commandery and fortified Juyong Pass.[35]

The Han dynasty, which followed the short-lived Qin in 206 BC, initially restored some local autonomy. Liu Bang, the founding emperor of the Han dynasty, recognized a number of regional kingdoms including Yan, ruled by Zang Tu, who had joined the revolt that overthrew the Qin, seized the City of Ji and sided with Liu Bang in the war with Xiang Yu for supremacy. But Zang rebelled and was executed, and Liu granted the kingdom to his childhood friend Lu Wan. Later, Liu became mistrustful of Lu, and the latter fled the City of Ji to join the Xiongnu tribes of the steppes. Liu Bang's eighth son took control of Yan, which was subsequently ruled by lineal princes of the imperial family, from the City of Ji, then known as Yan Commandery (燕郡), and the Principality of Guangyang (广阳国/廣陽國). In the early Western Han, the four counties of Guangyang Principality had 20,740 households and an estimated population of 70,685.[36][Note 22]

In 106 BC, under Emperor Wu, the country was organized into 13 prefectural-provinces, or zhou (州), and the City of Ji served as the provincial capital for Youzhou (幽州), the territories of which extended from what is now central Hebei Province to the Korean Peninsula. The tomb of Liu Jian, the Prince of Guangyang who ruled Youzhou from 73 to 45 BC was discovered in Fengtai District in 1974 and has been preserved in the Dabaotai Western Han Dynasty Mausoleum.[37] In 1999, another royal tomb was found in Laoshan in Shijingshan District but the prince formerly buried there has not been identified.[38][39]

During the early Eastern Han dynasty in 57 AD, the five counties of Guangyang Commandery had 44,550 households and an estimated 280,600 residents.[36][Note 22] By population density, Guangyang ranked in the top 20 among the 105 commanderies nationally.[36] In the late Eastern Han, the Yellow Turban Rebellion erupted in Hebei in 184 AD and briefly seized Youzhou. The court relied on regional militaries to put down the rebellion and Youzhou was controlled successively by warlords Liu Yu, Gongsun Zan, Yuan Shao and Cao Cao.[40] In 194 AD, Yuan Shao captured Ji from Gongsun Zan with the help of Wuhuan and Xianbei allies from the steppes.[40] Cao Cao defeated Yuan Shao in 200 AD and the Wuhuan in 207 AD to pacify the north.[40]

During the Three Kingdoms period, the Kingdom of Wei founded by Cao Cao's son, Cao Pi, controlled ten of the Han dynasty's prefectures including Youzhou and its capital Ji. The Wei court instituted offices in Youzhou to manage relations with the Wuhuan and Xianbei.[41] To help sustain the troops garrisoned in Youzhou, the governor in 250 AD built the Lilingyan, an irrigation system that greatly improved agricultural output in the plains around Ji.[41]

Ji was demoted to a mere county seat in the Western Jin dynasty, which made neighboring Zhuo County, in present-day Hebei Province, the prefectural capital of Youzhou. In the early 4th century, the Western Jin dynasty was overthrown by steppe peoples who had settled in northern China and established a series of mostly short-lived kingdoms. During the so-called Sixteen Kingdoms period, Beijing, still known as Ji, was controlled successively by the Di-led Former Qin, the Jie-led Later Zhao, and the Xianbei-led Former Yan and Later Yan. In 352, Prince Murong Jun, moved the capital of the Former Yan Kingdom from Manchuria to Ji, making the city a sovereign capital for the first time in over 500 years.[5] Five years later, the Former Yan's capital was moved further south to Ye in southern Hebei.[5] In 397 AD, the Northern Wei, another Xianbei regime, united northern China and restored Ji as the capital of Youzhou. While this designation continued through the remainder of the Northern Dynasties, the Eastern Wei, Northern Qi and Northern Zhou, the size of its jurisdiction shrank drastically, as the number of zhou in China was massively increased in this period, from 21 in the early 4th century to more than 200 in the late 6th century.

In 446, the Northern Wei built a Great Wall from Juyong Pass west to Shanxi to protect its capital, Datong, from the Rouran.[42] In 553–56, the Northern Qi extended this Great Wall eastward to the Bohai Sea to defend against the Göktürks, who raided Youzhou in 564 and 578.[43][44] Centuries of warfare severely depopulated northern China. During the Eastern Wei (534–550), Youzhou, Anzhou (modern Miyun) and East Yanzhou (modern Changping) had a combined 4,600 households and about 170,000 residents.[36][Note 22]

After the Sui dynasty reunited China in 589 AD, Youzhou was renamed Zhuojun or the Zhuo Commandery (涿郡), which was administered from Ji. In 609, Zhuo Commandery and neighboring Anle Commandery (modern Miyun) had a combined 91,658 households and an estimated population of 458,000.[36][Note 22] Emperor Yang of Sui built a network of canals from the Central Plain to Zhuojun to carry troops and food for the massive military campaigns against Goguryeo (Korea). Though the campaigns proved to be ruinous, they were continued by the Tang dynasty. In 645 AD, the Emperor Taizong of the Tang dynasty founded the Minzhong Temple (now Fayuan Temple) in the southeast of Ji to remember the war dead from the Korean Campaigns. The Fayuan Temple, now within Xicheng District, is one of the oldest temples in urban Beijing.

The Tang dynasty reduced the size of a prefecture, as a unit of administration administrative division, from a province to a commandery and renamed Zhuojun back to Youzhou, which was one of over 300 Tang Prefectures.[45] With the creation of a separate prefecture called Jizhou (薊州) in present-day Tianjin in 730, the name Ji was transplanted from Beijing to Tianjin, where a Ji County (蓟县) still exists today.[46] In Beijing, the City of Ji gradually became known as Youzhou. During the prosperous early Tang, Youzhou's ten counties tripled in size from 21,098 households and about 102,079 residents to 67,242 households and 371,312 residents in 742.[36][Note 22] In 742, Youzhou was renamed Fanyang Commandery (范陽郡), but reverted to Youzhou in 762.

To guard against barbarian invasions, the imperial court created six frontier military commands in 711 AD, and Youzhou became the headquarters of the Youzhou Jiedushi, who was tasked to monitor the Khitan and Xi nomads just north of present-day Hebei Province. In 755, the Jiedushi An Lushan launched a rebellion from Youzhou, and declared himself the emperor of the Great Yan dynasty. He went on to conquer Luoyang and Xi'an with a multi-ethnic army of Han, Tongluo, Xi, Khitan and Shiwei troops.[48] After An's death, Shi Siming continued the rebellion from Youzhou. Shi Siming's tomb was discovered in Wangzuo Village in Fengtai District in 1966 and excavated in 1981.[49] The An–Shi Rebellion lasted eight years and severely weakened the Tang dynasty. For the next 150 years, military governors ruled Youzhou autonomously.[50][51]

When the Tang dynasty was overthrown in 907 by the Later Liang dynasty, Youzhou remained independent and its military governor Liu Shouguang declared himself emperor of the short-lived Jie Yan dynasty in 911.[50][52] This regime was ended in 913 by the ethnic Shatuo general Li Cunxu who went on to found the Later Tang dynasty in 923.[50] The disintegration of the Tang dynasty into the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms paved the way for Khitan expansion into northern China, which prompted the rise of Beijing in Chinese history.[50][52]

The nomadic Khitan people were united under Yelü Abaoji, who founded the Liao dynasty in 916 and, from 917 to 928, tried seven times to take Youzhou.[52] In 936, a rift in the Later Tang court allowed Yelü Abaoji to help another ethnic Shatuo general Shi Jingtang found the third of the Five Dynasties, the Later Jin.[50] Shi Jingtang then ceded sixteen prefectures across the northern frontier including Youzhou, Shunzhou (modern Shunyi), Tanzhou (modern Changping) and Ruzhou (modern Yanqing) to the Liao dynasty.[50]

Liao, Song and Jin dynasties

Though Beijing was but a peripheral city to Chinese dynasties centered in Luoyang and Xi'an, it was an important entryway into China for tribal peoples to the north. The city's stature grew from the 10th century with successive invasions of China proper by the Khitans, Jurchens, and Mongols, who respectively founded the Liao dynasty, Jin dynasty and Yuan dynasty.

Liao Nanjing

In 938, the Liao dynasty renamed Youzhou, Nanjing (南京) or the "Southern Capital" and made the city one of four secondary capitals to the primary seat of power at Shangjing (in modern-day Baarin Left Banner, Inner Mongolia). The Liao retained the Tang configuration of the city, which had eight gates in its outer wall, two in each cardinal direction, an inner walled city, which was converted into palace complex, and 26 residential neighborhoods.[53]

Thus, the City of Ji, ceded to the Liao as Youzhou, continued as Nanjing in what is today the southwest part of urban Beijing. Some of the oldest landmarks in southern Xicheng (formerly Xuanwu) and Fengtai Districts date to the Liao era. They include Sanmiao Road, one of the oldest streets in Beijing[54] and the Niujie Mosque, founded in 996, and the Tianning Temple, built from 1100 to 1119. Under Liao rule, the population inside the walled city grew from 22,000 in 938 to 150,000 in 1113 (and the population of the surrounding region grew from 100,000 to 583,000) as large numbers of Khitan, Xi, Shiwei and Balhae from the north and Han from the south migrated to the city.[55][Note 22]

The Song dynasty, after unifying the rest of China in 960, sought to recapture the lost northern territories. In 979, Emperor Taizong personally led a military expedition that reached and laid siege to Nanjing (Youzhou) but was defeated in the decisive Battle of Gaoliang River, just northwest of present-day Xizhimen.

In 1120, the Song entered the Alliance on the Sea with the Jurchens, a semi-agricultural, forest-dwelling people living northeast of the Liao in modern-day Manchuria. The two nations agreed to jointly invade the Liao and split captured territories, with most of the Sixteen Prefectures going to the Song.[56] Under the leadership of Wanyan Aguda, who founded the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), the Jurchens captured in rapid succession the Liao's Upper, Central and Eastern Capitals.[57][58]

In the spring of 1122, the Liao court rallied around Prince Yelü Chun in Nanjing, and defeated two Song army advances.[58] After Yelü Chun died of illness in the early summer, Guo Yaoshi, an ethnic Han commander in the Liao Army, defected to the Song and led the vanguard of the Song Army in a raid on Nanjing.[58] The raiders entered the city, but the Liao Empress Xiao continued to resist from the walled palace complex.[59] After three days of street fighting, Liao reinforcements reached the city ahead of the main Song Army, and managed to expel Guo Yaoshi's forces.[58][59] In the winter of 1122, the Jin Army drove through the Juyong Pass and marched on Nanjing from the north.[58] This time, Empress Xiao fled to the steppes and the remaining Liao officials capitulated. Wanyan Aguda allowed the surrendering officials to retain their positions and encouraged refugees to return to the city, which was renamed Yanjing.[58]

Song Yanshan

In the spring of 1123, Wanyan Aguda agreed, as per treaty terms, to hand Yanjing and four other prefectures to the Song in exchange for tribute.[60] The handover occurred after the Jurchens had looted the city's wealth and forced all officials and craftsman to move to the Jin capital at Shangjing (near present-day Harbin).[60] Thus, the Song, having failed to take the city militarily from the Khitans, managed to purchase Yanjing from the Jurchens.[61] Song rule of the city, renamed Yanshan (燕山), was short-lived.

As the convoy of relocated Nanjing residents passed Pingzhou (near Qinhuangdao) on their way to the Northeast, they persuaded the governor Zhang Jue to restore them to their home city. Zhang Jue, a former Liao official who had surrendered to the Jin dynasty, then switched his allegiance to the Song.[60] Emperor Huizong welcomed his defection, ignoring warnings from his diplomats that the Jurchens would regard the acceptance of defectors as a breach of the treaty.[60] The Jurchens defeated Zhang Jue who took refuge with Guo Yaoshi at Yanshan.[60] The Song court had Zhang Jue executed to satisfy Jin demands, much to the alarm of Guo Yaoshi and other former Liao officials serving the Song.[60]

The Jurchens, sensing Song weakness, used the Zhang Jue incident as a pretext to invade. In 1125, Jin forces defeated Guo Yaoshi at the Battle of the Bai River, on the upper reaches of the Chaobai River in modern Miyun County.[62] Guo Yaoshi then surrendered Yanshan and then guided the Jin's rapid advance on the Song capital, Kaifeng, where the Song emperors Huizong and Qinzong were captured in 1127, ending the Northern Song dynasty.[62] Yanshan was renamed Yanjing.

Jin Zhongdu

In 1153 the Jin emperor Wanyan Liang moved his capital from Shangjing to Yanjing and the city was renamed Zhongdu (中都) or the "Central Capital".[32] For the first time in its history, the city of Beijing became a political capital of a major dynasty.

The Jin expanded the city to the west, east, and south, doubling its size. On today's map of urban Beijing, Zhongdu would extend from Xuanwumen in the northeast to the Beijing West railway station to the west, and south to beyond the southern 2nd Ring Road. The walled city had 13 gates, four in the north and three openings in each of the other sides. Remnants of Zhongdu city walls are preserved in Fengtai District.[64] The Jin emphasized the centrality of the regime by placing the walled palace complex near the center of Zhongdu. The palace was situated south of present-day Guang'anmen and north of the Grand View Garden.[65] In 1179, Emperor Zhangzong had a country retreat built northeast of Zhongdu. Taiye Lake was excavated along the Jinshui River[66] and Daning Palace (大寧宮/大宁宫) was erected on Qionghua Island in the lake.[67][Note 23] The grounds of this palace is now Beihai Park.

Paper money was first issued in Beijing during the Jin.[68] The Lugou Bridge, over the Yongding River southwest of the city, was built in 1189. Seventeen Jin emperors are buried in Fangshan District, including those whose tombs were originally built in Shangjing and moved to Zhongdu.[69] The city's population grew from 82,000 in 1125 to 400,000 in 1207 (and from 340,000 in the surrounding region to 1.6 million).[70][Note 22]

.jpeg.webp)

Zhongdu served as the Jin capital for more than 60 years, until the onslaught of the Mongols in 1214.[71] The Mongols, a tribal nomadic people from the Mongolian Plateau and southern Siberia, had assisted the Jurchen in the war against the Khitans, but were not given the promised compensation. In 1211, the Mongols led by Genghis Khan took revenge against the Jin by invading northern China. By 1213, he had controlled most of Jin territory north of the Yellow River with the exception of the capital Zhongdu. In March 1214, he set up headquarters in Zhongdu's northern suburbs and with brother Hasar and three eldest sons, Jochi, Chagatai and Ögedei, began to besiege the city.[72] Though the Jin court was weakened by a palace coup, the city was protected by three layers of moats and 900 towers.[73] When disease broke out within the Mongol ranks, Genghis Khan sent Muslim envoy Ja'far into the city to negotiate, and the Jin court agreed to a peace treaty by ceding territory and accepting vassal status. Among Genghis Khan's demands was marriage to a Jurchen princess. The Qicheng Princess, daughter of Wanyan Yongji, was designated for the Mongol chieftain.[74][75] She along with 100 guards, 500 boys and girl servants, 3,000 bolts of cloth, and 3,000 horses were sent to the Mongol camp.[76] The Qicheng Princess became one of the four main wives of Genghis Khan, who lifted the siege and withdrew north of the Juyong Pass.

Emperor Xuanzong, after considerable debate, decided to move the capital from Zhongdu to Kaifeng further to the south. In June 1214, as the Jin imperial procession departed the city, a detachment of Khitan guards rebelled at the Lugou Bridge and defected to the Mongols. Genghis Khan believed the Jin was trying to rebuild military strength further south in breach of the terms of peace and decided to reinvade the Jin. By winter, Mongol troops were again besieging Zhongdu.[77]

In 1215, after a bitter siege in which many of the city's inhabitants starved, Zhongdu's 100,000 defenders and 108,000 households surrendered.[78] The city was still looted and burned by the invaders.[79] Zhongdu was renamed Yanjing and its population shrank to 91,000 in 1216 (with 285,000 in the surrounding region).[70][Note 22] Among the captives taken from the city was a Khitan named Yelü Chucai, who persuaded Genghis Khan that while China could be conquered from the saddle, it could not be ruled from the saddle. Rather than converting northern China into pastures, it would be more beneficial for Mongols to tax the agrarian population. Genghis Khan heeded the advice and the Mongol pillaging eased. The Mongols continued to the war against the Jurchens until the capture of Kaifeng in 1234 ended the Jin dynasty. Yelü Chucai was buried on the east bank of Kunming Lake in what is now the Summer Palace.[80]

In 1219, Genghis Khan invited the Daoist sage Qiu Chuji for advice on "keeping the empire in good order."[81] The 76-year old Qiu had previously declined invitations from the emperors of the Jin and Southern Song, but agreed to travel from Shandong to Yanjing and then to Central Asia, where, at the Mongol encampment in the Hindu Kush, he taught the Genghis Khan about the Dao, telling the great khan medicine for immortality did not exist[82] and urged him to preserve lives.[83] The Mongol leader called Qiu an immortal sage, made him the head Daoist priest of the empire and exempted Daoism from taxation. Qiu returned to Yanjing in 1224 and expanded what would become the White Cloud Temple, where he is buried and which is today the seat of the Chinese Daoist Association.[83]

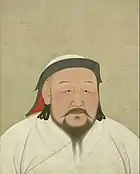

Yuan dynasty

When Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, visited Yanjing in 1261, much of the city lay in ruin,[84] so he stayed in the Daning Palace on Qionghua Island.[85] Unlike other Mongol leaders who wanted to retain the traditional tribal confederation based in Karakorum in Outer Mongolia, Kublai Khan was eager to become the emperor of a cosmopolitan empire. He spent the next four years waging and winning a civil war against rival Mongol chieftains and in 1264 ordered advisor Liu Bingzhong to build his new capital at Yanjing. In 1260, he had already begun construction of his capital at Xanadu, some 275 km (171 mi) due north of Beijing on the Luan River in present-day Inner Mongolia, but he preferred the location of Beijing. With the North China Plain opening to the south and the steppes just beyond the mountain passes to the north, Beijing was an ideal midway point for Kublai Khan's new seat of power.

In 1271, he declared the creation of the Yuan dynasty and named his capital Dadu (大都, Chinese for "Grand Capital",[86] or Daidu to the Mongols[87]). It is also known by the Mongol name Khanbaliq (汗八里), spelled Cambuluc in Marco Polo's account. Construction of Dadu began in 1267 and the first palace was finished the next year. The entire palace complex was completed in 1274 and the rest of the city by 1285.[88] In 1279, when Mongol armies finished off the last of the Song dynasty in southern China, Beijing became for the first time, the capital of the whole of China. After the construction of Dadu, Xanadu, also known as Shangdu, became Kublai Khan's summer capital.

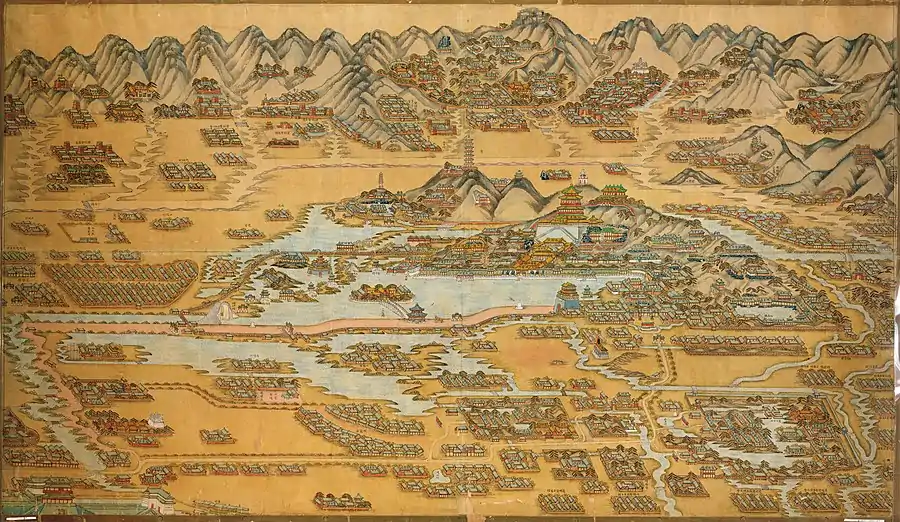

Rather than continuing on the foundation of Zhongdu, the new capital Dadu was shifted to the northeast and built around the old Daning Palace on Qionghua Island in the middle of the Taiye Lake. This move set in place Beijing's current north–south central axis. Dadu was nearly twice the size of Zhongdu. It stretched from present-day Chang'an Avenue in the south to the earthen Dadu city walls that still stand in northern and northeastern Beijing, between the northern 3rd and 4th Ring Roads.[89] The city had earthen walls 24 m thick and 11 city gates, two in the north and three each in the other cardinal directions. Later, the Ming dynasty lined portions of Dadu's eastern and western walls with brick and retained four of the gates. Thus, Dadu had the same width as the Beijing of the Ming and Qing dynasties. The geographic center of the Dadu was marked with a pavilion, which is now the Drum Tower.

The most striking physical feature of Dadu was the string of lakes in the heart of the city. These lakes were created from the Jinshui River[91] inside the city.[66] They are now known as the six seas ("hai") of central Beijing: Houhai, Qianhai, and Xihai (the Rear, Front, and Western Seas) which are collectively known as Shichahai; Beihai (the North Sea); and Zhonghai and Nanhai which are collectively known as Zhongnanhai. Qionghua Island is now the island in Beihai Park on which the White Dagoba stands. Like today's Chinese leaders, the Yuan imperial family lived west of the lakes in the Xingsheng (兴圣宫) and Longfu (隆福宫) Palaces.[92] A third palace east of the lakes, called the Danei (大内), at the site of the later Forbidden City, housed the imperial offices. The city's construction drew builders from all over the Mongols' Asian empire, including local Chinese as well as those from places such as Nepal and Central Asia.[93] Liu Bingzhong was appointed as the supervisor of the construction of the imperial city and a chief architect was Yeheidie'erding. The pavilions of the palaces took on various architectural styles from across the empire. The entire palace complex occupied the south central portion of Dadu. Following Chinese tradition, the temples for ancestral rites and harvest rites were built, respectively, to west and east of the palace.[94]

.jpg.webp)

The inclusion of the Jinshui and Gaoliang rivers gave Dadu a larger supply of water than the Lotus Pool which had nourished Ji, Youzhou, and Nanjing for the previous 2,000 years.[66] To boost water supply even more, Yuan hydrologist Guo Shoujing built channels to draw additional spring water from Yuquan Mountain in the northwest through what is today the Kunming Lake of the Summer Palace through the Purple Bamboo Park to Jishuitan, which was a large reservoir inside Dadu.[95] The expansion and extension of the Grand Canal from Dadu to Hangzhou enabled the city to import greater volumes of grain to sustain a larger population. The completion of the Tonghui Canal in 1293 allowed barges from Tongzhou to sail through the city right to the gates of the imperial palace at Shichahai. In 1270, Dadu had a population of 418,000 and another 635,000 in the surrounding region.[70][Note 22] By 1327, the city had 952,000 residents with another 2.08 million in the surrounding region.[70]

The city's residential districts were laid out in a checkerboard pattern divided by avenues 25 m in width and narrow alleyways, called hutongs, 6–7 m wide.[96] One of the best surviving examples of such a district is Dongsi Subdistrict, which has 14 parallel hutongs, called the 14 tiao of Dongsi. The name hutong is unique to the Yuan-era city; in older neighborhoods that date to the Liao and Jin eras, narrow lanes are called jie or streets. Each of the large avenues had underground sewers which carried rain and refuse to the south of the city.[97] The main markets were located in Dongsi, Xisi and along the north shore of Jishuitan.[95]

As Kublai Khan had intended, the city was a showcase of the cosmopolitan Yuan Empire. A number of foreign travelers including Giovanni di Monte Corvino, Odoric of Pordenone, Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta left written accounts of visits to the city. Some of the most famous writers of the Yuan era including Ma Zhiyuan, Guan Hanqing and Wang Shifu, lived in Dadu. The Mongols commissioned the building of an Islamic observatory and Islamic academy. The White Stupa Temple near Fuchengmen was commissioned by Kublai Khan in 1271. Its famous white stupa was designed by Nepali architect Araniko, and remains one of the biggest stupas in China.[98] The Confucius Temple and Guozijian (Imperial Academy) were founded during the reign of Temür Khan, Emperor Chengzong, Kublai's successor.

Yuan rule was severely weakened by a succession struggle in 1328 known as the War of the Two Capitals in which the Dadu-based claimant to the throne prevailed over his Shangdu-based rival, but not after heavy fighting around Dadu and across the country among Mongol princes.[99]

Ming dynasty

In 1368, Zhu Yuanzhang founded the Ming dynasty in the Nanjing on the Yangtze River and his general Xu Da drove north and captured Dadu. The last Yuan emperor fled to the steppes. Dadu's imperial palace was razed and the city was renamed Beiping (北平 or "Northern Peace").[100] Nanjing, also known as Yingtian Fu became the Jingshi or the capital of the new dynasty. Two years later, Zhu Yuanzhang conferred Beiping to his fourth son, Zhu Di, who at the age of ten became the Prince of Yan. Zhu Di did not move to Beiping until 1380 but quickly built up his military power in defense of the northern frontier. His three older brothers all predeceased his father who died in 1398. The throne was passed on to Zhu Yunwen, the son of Zhu Di's oldest brother. The new emperor sought to curtail his uncle's power in Beiping, and a bitter power struggle ensued. In 1402, after a four-year civil war, Zhu Di seized Nanjing and declared himself the Yongle Emperor. As the third emperor of the Ming dynasty, he was not content to stay in Nanjing. He executed hundreds in Nanjing for remaining loyal to his predecessor, who was reportedly killed in a palace fire but was rumored to have escaped. The Yongle Emperor sent his eunuch Zheng He on the famed voyages overseas in part to investigate the rumors of the Jianwen Emperor abroad.

In 1403, the Yongle Emperor renamed his home base Beijing (北京, the "Northern Capital"), and elevated the city to the status of capital, on par with Nanjing. For the first time, Beijing took on its modern name, while the prefecture around the city gained the new name Shuntian Fu (顺天府).[101] From 1403 to 1420, Yongle prepared his new capital with a massive reconstruction program. Some of Beijing's most iconic historical buildings, including the Forbidden City and the Temple of Heaven, were built for Yongle's capital. The Temples of the Sun, Earth and Moon were later added by the Daoist Jiajing Emperor in 1530.

In 1421, Yongle moved the Jingshi of the Ming to Beijing, which made Beijing the main capital of the Ming dynasty. From Beijing, Yongle launched multiple campaigns against the Mongols. After he died in 1424, his son, the Hongxi Emperor, ordered the capital be moved back to Nanjing, but died of illness in 1425.[102] The Hongxi Emperor sent his son, the future Xuande Emperor, to Nanjing to prepare for the move, but the latter chose to keep the capital in Beijing after his accession to the throne.[103] Like his grandfather, the Xuande Emperor was interested in monitoring affairs on the northern frontier. Most of the Great Wall in northern Beijing Municipality were built during the Ming dynasty.

In the early Ming dynasty, the northern part of old Dadu was depopulated and abandoned. In 1369, the city's population had been reduced to 95,000, with only 113,000 in the surrounding region.[70][Note 22] A new northern wall was built 2.5 km (1.6 mi) to the south of the old wall, leaving the Jishuitan reservoir outside the city as part of the northern moat. A new southern wall for the city was built half a kilometer south of the southern Dadu wall. These changes completed the Inner City wall of Beijing, which had nine gates (three in the south and two each to the north, east and west).

The Inner City walls withstood a major test following the Tumu Crisis of 1449 when the Zhengtong Emperor was captured by Oirat Mongols during a military campaign near Huailai. The Oirat chieftain, Esen Tayisi, then drove through the Great Wall and marched on the Ming capital with the captive emperor in hand. Defense Minister Yu Qian rejected Esen's demands for ransom despite the Zhengtong Emperor's pleadings. Yu said the responsibility to protect the country took precedence over the Emperor's life. He rejected calls by other officials to move the capital to the South and instead elevated the Zhengtong Emperor's younger half-brother to the throne and assembled 220,000 troops to defend the city. Ming forces with firearms and cannons ambushed the Mongol cavalry outside Deshengmen, killing Esen's brother in the barrage, and repelled another attack on Xizhimen. Esen retreated to Mongolia and three years later, returned the captive Zhengtong Emperor with no ransom paid. In 1457, the Zhengtong Emperor reclaimed the throne and had Yu Qian executed for treason. Yu Qian's home near Dongdan was later made into a temple in his honor.[104]

Back in power, the Zhengtong Emperor, now ruling under the new era name of Tianshun, first promoted and then became distrustful of officials who had aided his restoration. One of them, the grand eunuch Cao Jixiang, decided to strike at the throne. In August 1461, Cao's adopted son, Cao Qin, launched a mutiny among ethnic Mongol troops stationed inside Beijing.[105] The plot was betrayed and the Tianshun Emperor ordered the gates of the Forbidden City and the Inner City closed, trapping the mutineers, who were unable to break into the palace complex and were killed.[105]

In 1550, Altan Khan led a Khalkha Mongol raid on Beijing that pillaged the northern suburbs but did not attempt to take the city. To protect the city's southern suburbs, including neighborhoods from the Liao and Jin-eras and the Temple of Heaven, the Outer City wall was built in 1553. The Outer City wall had seven gates, three to the south, two each to the east and west. The Inner and Outer Ming city walls stood until in the 1960s when all but a couple small sections were pulled down to build the Beijing Subway and the 2nd Ring Road.[106] The largest and best-preserved section of the wall is located in the Ming City Wall Relics Park near the southeast corner of the inner city.

Jesuit missions reached Beijing at the turn of the 16th century. In 1601, Matteo Ricci became an advisor to the imperial court of the Wanli Emperor and became the first Westerner to have access to the Forbidden City.[107] He established the Nantang Cathedral in 1605, the oldest surviving Catholic church in the city. Other Jesuits later became directors of Beijing's Imperial Observatory.

On the eve of the Tumu Crisis in 1448, the city had 960,000 residents with another 2.19 million living in the surrounding region.[70][Note 22] Beijing was the largest city in the world from 1425 to 1635 and from 1710 to 1825.[108] To feed the growing population, Ming authorities built and administered granaries, including the Imperial Granary and Jingtong storehouses near the terminus of the Grand Canal, which fed a growing population and sustained the military. The granaries helped control prices and prevent inflation, but price controls became less effective as the population grew and demand for food exceeded supply.

Until the mid-15th century, Beijing residents relied on wood for heating and cooking. The growing population led to massive logging of the forests around the city. By the mid-15th century, the forests had largely disappeared. As a substitute, residents turned to coal, which was first mined in the Western Hills during the Yuan dynasty and expanded in the Ming. The use of coal caused many environmental problems and changed the ecological system around the city.

During the Ming dynasty, 15 epidemic outbreaks occurred in the city of Beijing including smallpox, "pimple plague" and "vomit blood plague" - the latter two were possibly bubonic plague and pneumonic plague. In most cases, the public health system functioned well in gaining control of the outbreaks, except in 1643. That year, epidemics claimed 200,000 lives in Beijing, thus compromising the defense of the city from the attacks of the peasant rebels and contributing to the downfall of the dynasty.

During the 15th and 16th centuries, banditry was common near Beijing despite the presence of imperial government. Due to inadequate supervision and economic privation, imperial troops in the capital region to protect the throne would often turn to brigandage. Officials responsible for eradicating banditry often had ties to brigands and other marginal elements of Ming society.[109]

During the late Ming dynasty, Beijing faced threats from both within and beyond the Great Wall. In 1629, the Manchus, who were descendants of the Jurchens, raided Beijing from the Manchuria, but were defeated outside the outer city walls at Guangqumen and Zuoanmen by Ming commander Yuan Chonghuan.[110] After retreating north, Manchu leader, Hong Taiji, through treachery, deceived the Ming dynasty's Chongzhen Emperor into believing that Yuan Chonghuan had actually betrayed the Ming. In 1630, the Chongzhen Emperor had Yuan executed in public at Caishikou through death by a thousand cuts.[111] Yuan was rehabilitated 150 years later by the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing dynasty and his tomb near Guangqumen is now a shrine.[112]

Also in 1629, Li Zicheng launched a peasant rebellion in northwest China and, after 15 years of conquest, captured Beijing in March 1644. The Chongzhen Emperor committed suicide by hanging himself from a tree in Jingshan. Li proclaimed himself emperor of the Shun dynasty, but he was defeated at Shanhaiguan by Ming general Wu Sangui and the Manchu Prince Dorgon. Wu had defected to the Manchus and allowed them inside the Great Wall. They drove Li Zicheng from Beijing in late April.

Qing dynasty

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

On May 3, 1644, the Manchus seized Beijing in the name of freeing the city from the rebel forces of Li Zicheng.[113] Dorgon held a state funeral for the Chongzhen Emperor of the Ming dynasty and reappointed many Ming officials. In October, he moved the child Shunzhi Emperor from the old capital Shenyang into the Forbidden City and made Beijing the new seat of the Qing dynasty. In the following decades, the Manchus would conquer the rest of the country and ruled China for nearly three centuries from the city.[114] During this era, Beijing was also known as Jingshi which corresponds with the Manchu name Gemun Hecen.[115] The city's population, which had fallen to 144,000 in 1644, rebounded to 539,000 in 1647 (the population of the surrounding area rose from 554,000 to 1.3 million).[70][Note 22]

The Qing largely retained the physical configuration of Beijing inside the city walls. Each of the Eight Banners, including the Manchu, Mongol, and Han Banners were assigned to guard and live near the eight gates of the Inner City.[113] Outside the city, the Qing court seized large tracts of land for Manchu noble estates.[113] Northwest of the city, Qing emperors built several large palatial gardens. In 1684, the Kangxi Emperor built the Changchun Garden on the site of the Ming dynasty's Qinghua (or Tsinghua) Garden (outside today's west gate of Peking University). In the early 18th century, he began building the Yuanmingyuan, also known as the "Old Summer Palace", which the Qianlong Emperor expanded with European Baroque-style garden pavilions. In 1750, the Qianlong Emperor built the Yiheyuan, commonly referred to as the "Summer Palace". The two summer palaces represent both the culmination of Qing imperial splendor and its decline. Both were ransacked and razed by invading Western powers in the late Qing dynasty.

The Beijing dialect eventually became the official national language for the country. In the early Qing dynasty, Han officials serving in the imperial court were required to learn the Manchu language, but most Manchus eventually learned to speak Chinese.[116] The Manchus adopted Beijing Mandarin as their spoken language and this was a feature of Manchu Banner garrisons in areas of southern China. In 1728, the Yongzheng Emperor, who could not understand officials from southern China, decreed that all takers of the civil service examination must be able to speak Beijing Mandarin.[116][117] Though the decree was eventually lifted under the Jiaqing Emperor, the Beijing dialect spread first among officials and then among commoners under subsequent regimes.[116] Shortly after the founding of the Republic of China, the Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation made the Beijing dialect the national standard for spoken Chinese in 1913. After the capital was moved to Nanjing, National Languages Committee reaffirmed the Beijing dialect as the standard in 1932. The People's Republic of China followed suit in 1955.[116]

The Qing dynasty maintained a relatively stable supply of food for the population of the capital during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. The government's grain tribute system brought food from the provinces and kept grain prices stable. Soup kitchens provided relief to the needy. The secure food supply helped the Qing court maintain a degree of political stability.[118] Temple fairs such as the Huguo Fair, which are like monthly bazaars held around temples, added to the commercial vibrance of the city. At the height of the Qianlong Emperor's reign in 1781, the city had a population of 776,242 (and another 2.18 million in the surrounding region).[70][Note 22] Thereafter, Qing authorities began to restrict inward migration to the city.[119] A century later, the census of 1881–82 showed similar figures of 776,111 and 2.45 million.[70][Note 22]

In 1790, the Qing court's Nanfu office, which was in charge of organizing entertainment for the emperor, invited the dramatic opera troupes from Anhui to perform for the Qianlong Emperor. Under the Qianlong Emperor, the Nanfu had up to a thousand employees, including actors, musicians, and court eunuchs. In 1827, the Daoguang Emperor, the Qianlong Emperor's grandson, changed the name from Nanfu to Shengpingshu, and reduced the number of performances.[120] Nevertheless, the court invited opera troupes from Hubei came to perform. The Anhui and Hubei operatic styles eventually blended together in the mid-19th century to form Peking Opera.

Most of Beijing's oldest business establishments date to the Qing era. Tongrentang, opened in 1669 by a royal physician, became the sole supplier of herbal medicine to the Qing court in 1723. Baikui Laohao, the Hui Muslim restaurant serving traditional Beijing cuisine, opened its first store next to the Longfu Temple in 1780. Roast duck was part of the imperial menu dating back to the Yuan dynasty and restaurants serving Anas peking to the public opened in the 15th century, but it was Quanjude, which opened in 1864 and introduced the "hung oven", that made Peking Duck world-famous.

In 1813, some 200 adherents of the White Lotus sect launched a surprise siege on the Forbidden City but were repelled.[113] In response, authorities imposed the baojia system of social surveillance and control.

The British diplomat Lord Macartney's mission to China arrived in Beijing in 1792, but failed to persuade the Qianlong Emperor to ease trade restrictions or to permit a permanent British Embassy in the city. Nevertheless, Macartney observed weaknesses within the Qing regime, which would influence future Sino-British conflicts.

In 1860, during the Second Opium War, Anglo-French expeditionary forces defeated a Qing army at Baliqiao east of Beijing. They captured the city and sacked the Summer Palace and Old Summer Palace. Lord Elgin, the commander of the expedition, ordered the burning of the Old Summer Palace in retaliation of Qing mistreatment of Western prisoners. He spared the Forbidden City, saving it as a venue for the treaty-signing ceremony. Under the Convention of Peking that ended the war, the Qing government was forced to allow Western powers to establish permanent diplomatic presence in the city. The foreign embassies were based southeast of the Forbidden City in the Beijing Legation Quarter.

In 1886, Empress Dowager Cixi had the Summer Palace rebuilt using funds originally designated for the imperial navy, the Beiyang Fleet.[113] After the Qing government was defeated by Japan in the First Sino-Japanese War and forced to sign the humiliating Treaty of Shimonoseki, Kang Youwei assembled 1,300 scholars outside Xuanwumen to protest the treaty and drafted a 10,000-character appeal to the Guangxu Emperor. In June 1898, the Guangxu Emperor adopted the proposals of Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao and other scholars and launched the Hundred Days' Reform. The reforms alarmed Empress Dowager Cixi, who, with the help of Ronglu and Beiyang military commander Yuan Shikai, launched a coup. The Guangxu Emperor was imprisoned, Kang and Liang fled abroad, and Tan Sitong and five other scholar reformers were publicly beheaded at Caishikou outside Xuanwumen. One legacy of the short-lived reform era was the founding of Peking University in 1898. The university would have a profound impact on the intellectual and political history of the city.

In 1898, a millenarian group called the Righteous Harmony Society Movement formed in Shandong Province, calling for the expulsion of all foreign influence in China.[121] They attacked Westerners especially missionaries and converted Chinese, and were called the "Boxers" by Westerners. The Qing court initially suppressed the Boxers but the Empress Dowager attempted to use them to curtail foreign influence and permitted them to gather in Beijing, then expelled the Boxers from the city after ransacking occurred and ordered the foreigners in the legations to leave to Tianjin, which they refused to do. In June 1900, the Qing forces including Manchu Bannerman and Muslim fighters from Gansu and the Boxers besieged the Legation Quarter, which sheltered several hundred foreign civilians and soldiers and about 3,200 Chinese Christians. The first attempt by the foreign Eight-Nation Alliance in the Seymour Expedition was defeated and forces to turn back. On the second attempt, eventually they defeated the Boxers and Qing troops and lifted the siege. The foreign armies looted the city and occupied Beijing and the surrounding area in Zhili. Empress Dowager Cixi fled to Xi'an and did not return until after the Qing government had signed the Boxer Protocol which compelled it to pay reparations of 450 million taels of silver with interest at four percent. The Boxer indemnities stripped the Qing government of much of its tax revenues and further weakened the state.[122]

The United States used its portion of the proceeds to fund scholarships for Chinese students studying in America. In 1911, the Boxer Indemnity Scholar Program established the American Indemnity College in the Qinghua Gardens northwest of Beijing as a preparatory school for students planning to study abroad. In 1912, the school was renamed Tsinghua University, and remains to this day, one of the finest institutions of higher learning in China.

After the Boxer Rebellion, the struggling Qing dynasty accelerated the pace of reform and became more receptive to foreign influence. The centuries-old imperial civil service examination was abolished in 1905, and replaced with a Western-style curriculum and degree system. Public education for women received greater emphasis and even drew support from reactionaries like the Empress Dowager.[123] Beijing's school for girls in the late Qing period made unbound feet an entrance requirement. The Beijing Police Academy, founded in 1901 as China's first modern institution for police training, used Japanese instructors and became a model for police academies in other cities. The Peking Union Medical College, founded by missionaries in 1906 and funded by the Rockefeller Foundation from 1915, set the standard for the training of nurses.[124] The Metropolitan University Library in Beijing, founded in 1898, was China's first modern academic library devoted to serving public higher education.[125][126]

Also in 1905, the Board of Revenue and private investors founded the Hubu Bank, China's first central bank and largest modern bank.[127] This bank was renamed the Bank of China after the Xinhai Revolution and began Beijing's tradition as the center of state banks in China. Large foreign banks including the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corp. (HSBC), National City Bank (Citibank), Deutsch-Asiatische Bank and Yokohama Specie Bank opened branches in the Legation Quarter. The building of railroads was capital intensive and required large-scale financing and foreign expertise. Beijing's earliest railroads were designed, financed and built under the supervision of foreign concerns.

The first railway in China was built in Beijing in 1864 by a British merchant to demonstrate the technology to the imperial court.[128] About 600 meters of tracks were laid outside Xuanwumen.[128] The steam locomotive shook the neighborhood and alarmed the capital guards.[129] The Qing court looked on the strange contraption with disfavor and had the railway dismantled.[128] To secure the support of Empress Dowager Cixi for railway construction, Viceroy Li Hongzhang imported a small train set from Germany and in 1888 built a 2-km narrow gauge railway from her residence in Zhongnanhai to her dining hall in Beihai.[130] The Empress, concerned that the locomotive's noise would disturb the geomancy or fengshui of the imperial city, required the train be pulled by eunuchs instead of steam engine.[130]

The city's first commercial railway, Tianjin-Lugouqiao Railway, was built from 1895 to 1897 with British financing.[130] It ran from the Marco Polo Bridge to Tianjin. The rail terminus was extended closer to the city to Fengtai and then to Majiapu, just outside Yongdingmen, a gate of the Outer City wall.[130] The Qing court resisted the extension of railways inside city walls.[130] Foreign powers who seized the city during the Boxer Rebellion extended the railway inside the outer city wall to Yongdingmen in 1900 and then further north to Zhengyangmen (Qianmen) just outside the Inner City wall in 1903.[130] They built an eastern spur to Tongzhou to carry grain shipped from the south on the Grand Canal. This extension breached the city wall at Dongbianmen.[130] The Lugouqiao-Hankou Railway, financed by French-Belgian capital and built from 1896 to 1905, was renamed Beijing-Hankou Railway after it was routed to Qianmen from the west.[131] This required the partial demotion of the Xuanwumen barbican. The completion of the Beijing–Fengtian Railway in 1907 required a similar break in Chongwenmen's fortification.[131] Thus, began the tearing down of city gates and walls to make way for rail transportation. The first railway in China built without foreign assistance was the Imperial Beijing-Zhangjiakou Railway. Built from 1905 to 1909, it was designed by Zhan Tianyou and terminated just outside Xizhimen.[131] By the late Qing dynasty, Beijing had rail connections to Hankou (Wuhan), Pukou (Nanjing), Fengtian (Shenyang) and Datong, and was a major railway hub in North China.

.jpg.webp)

Republic of China

The Qing dynasty was overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 but the capital of the newly founded Republic of China remained in Beijing as former Qing general Yuan Shikai took control of the new government from revolutionaries in the south. Yuan and successors from his Beiyang Army ruled the Republic from Beijing until 1928 when Chinese Nationalists reunified the country through the Northern Expedition and moved the capital to Nanjing. Beijing was renamed Beiping. In 1937, a clash between Chinese and Japanese troops at the Marco Polo Bridge outside Beiping triggered the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Japanese occupiers created a collaborationist government in northern China and reverted the city's name to Beijing to serve as capital for the puppet regime. After Japan's surrender in 1945, the city returned to Chinese rule and was again renamed Beiping. During the subsequent civil war between the Chinese Nationalists and Communists, the city was peacefully transferred to Communist control in 1949 and renamed Beijing to become the capital of the People's Republic of China.

Xinhai Revolution

When the Wuchang Uprising erupted in October 1911, the Qing court summoned Yuan Shikai and his powerful Beiyang Army to suppress the insurrection. As he fought revolutionaries in the south, Yuan also negotiated with them. On January 1, 1912, Dr. Sun Yat-sen, who returned from exile, founded the Republic of China in Nanjing and was elected provisional president. The new government was not recognized by any foreign powers, and Sun agreed to cede leadership to Yuan Shikai in exchange for the latter's assistance in ending the Qing dynasty. On February 12, Yuan compelled the Qing court, under the regency of Prince Chun, to abdicate. Empress Dowager Longyu signed the abdication agreement on behalf of the five-year-old Last Emperor, Puyi. The following day Sun resigned from the provisional presidency and recommended Yuan for the position. Under the terms of the imperial abdication, the Puyi would retain his dignitary title and staff and receive an annual stipend of 4 million Mexican silver dollars from the Republic. He was permitted to continue to reside in the Forbidden City for a time but was required to eventually move to the Summer Palace. His tomb and rituals were to be maintained at the expense of the Republic. The abdication ended the Qing dynasty and averted further bloodshed in the revolution.

As a condition for ceding leadership to Yuan, Sun insisted that the provisional government remain in Nanjing. On February 14, the Provisional Senate initially voted 20–5 in favor of making Beijing the capital over Nanjing, with two votes going for Wuhan and one for Tianjin.[132] The Senate majority wanted to secure the peace agreement by taking power in Beijing.[132] Zhang Jian and others reasoned that having the capital in Beijing would check against Manchu restoration and Mongol secession. But Sun and Huang Xing argued in favor of Nanjing to balance against Yuan's power base in the north.[132] Li Yuanhong presented Wuhan as a compromise.[133] The next day, the Provisional Senate voted again, this time, 19–6 in favor of Nanjing with two votes for Wuhan.[132] Sun sent a delegation led by Cai Yuanpei and Wang Jingwei to persuade Yuan to move to Nanjing.[134] Yuan welcomed the delegation and agreed to accompany the delegates back to the south.[135] Then on the evening of February 29, riots and fires broke out in all over the city.[135] They were allegedly started by disobedient troops of Cao Kun, a loyal officer of Yuan.[135] Disorder among military ranks spread to Tongzhou, Tianjin and Baoding.[135] These events gave Yuan the pretext to stay in the north to guard against unrest. On March 10, Yuan was inaugurated in Beijing as the provisional president of the Republic of China.[136] Yuan based the executive office and residence in Zhongnanhai, next to the Forbidden City. On April 5, the Provisional Senate in Nanjing voted to make Beijing the capital of the Republic and convened in Beijing at the end of the month.

In August, Sun Yat-sen traveled to Beijing where he was welcomed by Yuan Shikai and a crowd of thousands.[137] At the Huguang Guild Hall, the Revolutionary Alliance (Tongmenghui) led by Sun, Huang Xing and Song Jiaoren joined several smaller parties to form the Kuomintang.[138] The first national assembly elections were held from December 1912 to January 1913. Adult males over the age of 21 who were educated or owned property and paid taxes and who could prove two-year residency in a particular county could vote.[139] An estimated 4–6% of China's population were registered for the election.[140] The Nationalist Party won a majority in both houses of the National Assembly, which convened in Beijing in April 1913.[140]

As the assembly set out to ratify the constitution, Yuan resisted efforts to share power. Without the assembly's knowledge, he arranged for the large and expensive Reorganization Loan from a consortium of foreign lenders to fund his military. The loan, signed into effect at the HSBC Bank in the Legation Quarter, effectively surrendered the government's collection of salt tax revenues to foreign control.[141] Yuan's agents assassinated Nationalist leader Song Jiaoren in Shanghai.[142] In response, Sun Yat-sen launched a Second Revolution in July 1913, which failed and forced him into exile. Yuan then forced the National Assembly to elect him as the president and expel Nationalist members. In early 1914, he dissolved the National Assembly and abolished the provisional constitution in May.[143] On December 23, 1915, Yuan declared himself emperor, and his regime, the Empire of China (1915–1916). This declaration provoked the National Protection War as provinces in the south rebelled. Yuan was forced to step down from emperor to president in March 1916. He died in Beijing in June 1916, leaving military men from the Beiyang Army vying for control of the government. Over the next 12 years, the Beiyang Government in Beijing had no fewer than eight presidents, five parliaments, 24 cabinets, at least four constitutions and one brief restoration of the Manchu Monarchy.[144]

Unlike prior dynastic changes, the end of Qing rule in Beijing did not cause a substantial decline in the city's population, which was 785,442 in 1910, 670,000 in 1913 and 811,566 in 1917.[145] The population of the surrounding region grew from 1.7 to 2.9 million over the same period.[70] In 1917, Beijing was the fourth largest city in China after Guangzhou, Shanghai and Hankou, and the seventh largest capital city in the world.[146]

World War I and the May 4th Movement

After Yuan's death, Li Yuanhong became president and Duan Qirui, the prime minister, and the National Assembly was reconvened. The government soon faced a crisis over whether to enter World War I on the side of the Allied Powers or remain neutral. Li dismissed Duan, who favored entry into the war, and invited warlord Zhang Xun to the capital to mediate. Zhang and his pigtailed loyalist army marched into Beijing, dissolved the National Assembly and restored Puyi as Qing emperor on July 1.[147] Li fled to the Japanese Embassy in the Legation. The imperial restoration lasted just 12 days as Duan Qirui's army reclaimed the capital, and sent Zhang seeking refuge in the Dutch Embassy. Under Duan's command, China declared war on the Central Powers and sent 140,000 Chinese laborers to work on the Western Front. With financial backing from Japan, Duan then engineered the election of a new parliament in 1918 that was stacked his supporters from the Anhui clique. The so-called Anfu Parliament was named after Anfu Hutong, near Zhongnanhai where Duan's Anhui-based supporters congregated.

In the spring of 1919, the Republic of China, as a victor nation sent a delegation to the Paris Peace Conference seeking the return of German concession in Shandong Province to China. Instead, the Treaty of Versailles gave those possessions to Japan. News of the treaty sparked outrage in the Chinese capital. On May 4, 3,000 students from 13 universities in Beijing gathered in Tiananmen Square to protest the betrayal of China by the other Western powers and the corruption of the Anfu government by Japanese financial support. They marched toward the foreign legation but were blocked and proceeded to the home of deputy foreign minister Cao Rulin, who had attended the Peace Conference and was known to be friendly to Japanese interests. They razed Cao's residence and beat up Zhang Zongxiang, another pro-Japanese diplomat. The police arrested 32 students, which provoked further protests and arrests. Within weeks, the movement had spread to 200 cities and towns in 22 provinces. Workers in Shanghai struck and merchants closed shops in support of the protests. By late June, the government pledged not to sign the treaty, removed Cao and Zhang from office and released students from jail.

The May Fourth Movement began a tradition of student activism in Beijing and had a profound political and cultural impact on modern China. Leading intellectuals including Cai Yuanpei and Hu Shih at Peking University, encouraged the development of new culture to replace the traditional order. The movement also heightened the appeal of Marxism-Leninism as Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao, prominent May 4 figures, became early leaders of the Chinese Communist Party. Among the many youth who flocked to the Chinese capital during this period was a student from Hunan named Mao Zedong who worked as a library assistant under Li Dazhao at Peking University. Mao left the city for Shanghai in 1920 where he helped found the Chinese Communist Party in 1921. He did not return to Beijing until almost 30 years later.

Beiyang regime

In the 1920s, military strongmen of the Beiyang Army split into cliques and vied for control of the Republican government and its capital. In July 1920, Duan's government, weakened by the May 4 Protests, was driven out of Beijing by Wu Peifu and Cao Kun of the Zhili clique in the Zhili–Anhui War. Two years later, the Zhili Clique fought off a challenge by Zhang Zuolin and his Manchuria-based Fengtian clique in the First Zhili–Fengtian War. When the two sides squared off again in Second Zhili–Fengtian War in 1924, one of Wu's officers Feng Yuxiang launched the Beijing Coup. On October 23, 1924, Feng seized the capital, imprisoned President Cao Kun, restored Duan Qirui as the head of state and invited Sun Yat-sen to Beijing for peace talks. At that time, Sun was building a Nationalist regime in Guangzhou with the assistance of the Soviet Comintern and support of the Chinese Communist Party. Sun was stricken with cancer when he arrived in Beijing in early 1925 for one last effort to heal the north–south divide. He was welcomed by hundreds of civic organizations and called on Duan to include broad segments of civil society in reconstructing a united government. He died in Beijing on March 12, 1925, and was entombed at the Temple of Azure Clouds.

Zhang Zuolin and Wu Peifu joined forces against Feng Yuxiang, who relied on support from the Soviet Union. Feng took a generally accommodating stance toward the Nationalist and Communist parties which were active in spreading influence in the city. During this period, Beijing was a hotbed of student activism. In the May 30th Movement of 1925, 12,000 students from 90 schools marched through Wangfujing to Tiananmen in support of protesters in Shanghai.[148] With the opening of private colleges such as Yenching University in 1919 and the Catholic University of Peking in 1925, the student population in Beijing grew substantially in the early 1920s.[148] Middle school students also joined the protests.[148] In October, students protested against imperialism during an international conference on customs and tariffs held in the city.[149] In November, Li Dazhao organized the "Capital Revolution" a protest by students and workers demanding Duan's resignation. The protest was more violent, burning down a major newspaper office, but was disbanded.[150]

Though the Nationalists, under Sun's leadership, had allied with the Communists in the struggle against warlords, this alliance was not without tension. In November 1925, a group of right-wing Nationalist leaders met in the Western Hills and called for the expulsion of Communists from the Nationalist Party and severance of ties with the Comintern including advisor Mikhail Borodin.[149][151] This manifesto was denounced by the Nationalists' party center in Guangzhou led by Chiang Kai-shek, Wang Jingwei, and Hu Hanmin, and members of the so-called "Western Hills Group" were either expelled or left out of the party leadership.[152] They moved to Shanghai and regained power during the rupture between the Nationalists and Communists in April 1927.

On March 17, 1926, Feng Yuxiang's Guominjun troops at Dagu Fort near Tianjin exchanged fire with Japanese warships carrying Zhang Zuolin's Fengtian troops. Japan accused the Chinese government of violating the Boxer Protocol and, with the other seven Boxer Powers, issued an ultimatum demanding the removal of all defenses between Beijing and the sea as set forth under the Protocols. The ultimatum provoked student protests in Beijing that were jointly organized by the left-wing Nationalists and Communists. Two thousand students marched on Duan Qirui's executive office and called for the abrogation of the unequal treaties.[153] Police opened fire and killed over 50 and wounded 200 in what became known as the March 18 Massacre.[154] The government issued warrants for the arrest of Nationalists and Communists including Li Dazhao, who fled to the Soviet Embassy in the Legation quarters.[153] Within weeks, Feng Yuxiang was defeated by Zhang Zuolin and Duan's government fell. After Zhang took power on May 1, 1926, both the Nationalists and Communists were driven underground.[155] A year later, Zhang Zuolin raided the Soviet Embassy in the Legation and seized Li Dazhao. Li and 19 others Communist and Nationalist activists were executed in Beijing on April 25, 1927.

Zhang Zuolin controlled the Beiyang Government until June 1928 when the Nationalists on the Northern Expedition led by Chiang Kai-shek and allies Yan Xishan and Feng Yuxiang jointly advanced on Beijing. Zhang left the city for Manchuria and was assassinated en route by the Japanese Kwantung Army. Beijing was handed over peacefully to the victorious Nationalists[156] who moved the capital and Sun Yat-sen's tomb to Nanjing. For the first time since 1421, Beijing was renamed Beiping 北平 (Wade–Giles: Peip'ing),[157] or "Northern Peace".[158] Following the Northern Expedition, Beijing was under the de facto control of Shanxi warlord Yan Xishan who had allied himself with Nationalists.[159] On 2 March 1929, the city was the place of a violent mutiny of soldiers who formerly belonged to the army of warlord Zhang Zongchang, a subordinate of Zhang Zuolin. Though the mutineers managed to seize the Yonghe Temple and spread terror in Beijing, their revolt was quickly suppressed.[160] The city was made the provincial capital of Hebei Province, but lost that status to Tianjin in 1930. During the Central Plains War in 1930, Yan Xishan briefly tried to establish a rival national government in Beijing but lost the city to Zhang Xueliang, the son of Zhang Zuolin who was allied with Chiang Kai-shek.[161]

%252C_China_-_Geographicus_-_Beijing-crow-1925.jpg.webp)

City planning in the 1920s

During the Beiyang period, Beijing transitioned from an imperial capital into a modern city. The city's population grew from 725,235 in 1912 to 863,209 in 1921.[162] The municipal government reconfigured city walls and gates, paved and widened streets, installed tram service and introduced urban planning and zoning rules. The authorities also built modern water utilities, improved urban sanitation, educated the public about the proper handling of food and waste and monitored outbreaks of infectious diseases. With these public health measures, infant mortality and life expectancy of the general population improved.[163]

Urban development also reflected changes in political attitudes as the republican form of government prevailed over the monarchy and attempts to reintroduce imperial rule.[164] One example of the newfound emphasis on civic rights over imperial tradition was the development of city parks in Beijing. The idea of the public park as a place where common people could relax in a pastoral setting came to China from the West via Japan. Public parks in Beijing were almost all converted from imperial gardens and temples, which had previously been off-limits to most commoners. The Beijing municipal government, local gentry and merchants all promoted the development of public parks to provide wholesome entertainment and reduce alcoholism, gambling, and prostitution. After the Beijing Coup of 1924, Feng Yuxiang evicted Puyi from the Forbidden City, which was opened to the public as the Palace Museum. Parks also provided places for commercial activities and the open exchange of political and social ideas for the middle and upper classes.[165]

The demotion of Beijing from national capital to a mere provincial city greatly constrained urban planners' initiatives to modernize the city. Along with political stature, Beiping also lost government revenue, jobs and jurisdiction. In 1921, large banks headquartered in Beijing accounted for 51.9% of bank capital held by the 23 most important banks in China.[166] That proportion fell to just 2.8% in 1928 and 0% in 1935, as wealth followed political power out of the city.[166] The city's jurisdiction also shrank as surrounding counties were redrawn into Hebei. For the first time since the Ming dynasty, city no longer had control over agricultural regions and watershed.[167] Even the power plant for the city's trolley system in Tong County fell outside the city's jurisdiction.[161] Appeals to Nanjing for the recovery of towns like Wanping and Daxing were denied.[168] The city, anchored by its historical relics and universities, remained a center for tourism and higher education and became known as "China's Boston."[169] In 1935, the city's population stood at 1.11 million, with another 3.485 million in the surrounding region.[70]

Second Sino-Japanese War

After Japan seized Manchuria through the Mukden Incident in 1931, Beiping was threatened by steady Japanese encroachment into northern China. The Tanggu Truce of 1933 gave control of the Great Wall to the Japanese and imposed a 100-km demilitarized zone south of the wall. This deprived Beiping of its northern defenses. The secret He-Umezu Agreement of May 1935 required the Chinese government to remove Central Army units from Hebei Province and suppress anti-Japanese activities by the Chinese public.[170] The Qin-Doihara Agreement of June 1935 compelled the Nationalist 29th Army, a former unit of Feng Yuxiang's Guominjun that fought the Japanese in defense of the Great Wall, to evacuate from Chahar Province. This army was relocated and confined to an area south of the Beiping near Nanyuan.[171] In November 1935, the Japanese created a puppet regime based in Tongzhou called the East Hebei Autonomous Council, which declared its independence from the Republic of China and controlled 22 counties east of Beiping, including Tongzhou and Pinggu in modern-day Beijing Municipality.

In response to the growing threat, the Palace Museum's art collection was removed to Nanjing in 1934 and air defense shelters were built in Zhongnanhai.[172] The influx of refugees from Manchuria and presence of university campuses made Beiping a hotbed for anti-Japanese sentiment. On December 9, 1935, the university students in Beiping launched the December 9th Movement to protest the creation Hebei–Chahar Political Council, a semi-autonomous authority to administer the remainder of Hebei and Chahar not yet under direct Japanese control.

On July 7, 1937, the 29th Army and the Japanese army in China exchanged fire at the Marco Polo Bridge near the Wanping Fortress southwest of the city. The Marco Polo Bridge Incident triggered the Second Sino-Japanese War, World War II as it is known in China. After continued clashes and failed cease-fire talks, Japanese reinforcements with air support launched a full-scale offensive against Beiping and Tianjin in late July. In fighting south of the city, deputy commander of the 29th Army Tong Lin'ge and division commander Zhao Dengyu were both killed in action. They along with Zhang Zizhong, another 29th Army commander who died later in the war, are the only three modern personages after whom city streets are named in Beijing.[Note 24] In Tongzhou, the collaborationist militia of the East Hebei Council refused to join the Japanese in attacking the 29th Army and mutinied, but Chinese forces had retreated to the south.[158][173] The city itself was spared of urban fighting and destruction that many other Chinese cities suffered in the war.

The Japanese created another puppet regime, the Provisional Government of the Republic of China, to manage occupied territories in northern China and designated Beiping, renamed Beijing, as its capital.[174] This government later merged with Wang Jingwei's Reorganized National Government of China, a collaborationist government based in Nanjing, though effective control remained with the Japanese military.[174]

During the war, Peking and Tsinghua Universities relocated to unoccupied areas and formed the National Southwestern Associated University. Furen University was protected by the Holy See's neutrality with the Axis Powers. After the outbreak of the Pacific War with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Japanese shut down Yenching University and imprisoned its American staff. Some were rescued by Communist partisans that waged guerrilla warfare in rural outlying areas. The village of Jiaozhuanghu in Shunyi District still has a labyrinth of tunnels with underground command posts, meeting rooms, and camouflaged entrances from the war.[175]