Jan Švankmajer | |

|---|---|

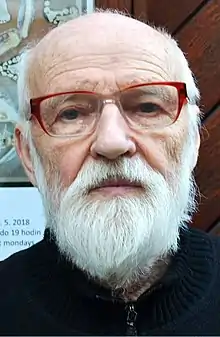

Jan Švankmajer in 2018 | |

| Born | 4 September 1934 |

| Occupation(s) | Film director, artist |

| Years active | 1964–present |

| Spouse | Eva Švankmajerová |

| Children | 2 |

Jan Švankmajer (Czech: [ˈjan ˈʃvaŋkmajɛr]; born 4 September 1934) is a Czech filmmaker and artist whose work spans several media. He is a self-labeled surrealist known for his stop-motion animations and features, which have greatly influenced other artists such as Terry Gilliam, the Brothers Quay, and many others.[1]

Life and career

Early life

Švankmajer was born in Prague. An early influence on his later artistic development was a puppet theatre he was given for Christmas as a child. He studied at the College of Applied Arts in Prague and later in the Department of Puppetry at the Prague Academy of Performing Arts, where he befriended Juraj Herz. He contributed to Emil Radok's film Johanes doctor Faust in 1958 and then began working for Prague's Semafor Theatre where he founded the Theatre of Masks. He then moved on to the Laterna Magika multimedia theatre, where he renewed his association with Radok.

As a filmmaker

This theatrical experience is reflected in Švankmajer's first film The Last Trick, which was released in 1964. Under the influence of theoretician Vratislav Effenberger, Švankmajer moved from the mannerism of his early work to classic surrealism, first manifested in his film The Garden (1968), and joined the Czechoslovak Surrealist Group.[2]

Švankmajer has gained a reputation over several decades for his distinctive use of stop-motion technique, and his ability to make surreal, nightmarish, and yet somehow funny pictures. Švankmajer's trademarks include very exaggerated sounds, often creating a very strange effect in all eating scenes. He often uses fast-motion sequences when people walk or interact. His movies often involve inanimate objects being brought to "life" through stop motion. Many of his films also include clay objects in stop motion, otherwise known as claymation. Food is a common subject and medium. Švankmajer also uses pixilation in many of his films, including Food (1992) and Conspirators of Pleasure (1996).

Stop-motion features in most of his work, though his feature films have included much more live-action sequences than animation.

Many of his movies, like the short film Down to the Cellar, are made from a child's perspective, while at the same time often having a truly disturbing and even aggressive nature. In 1972 the communist authorities banned him from making films, and many of his later films were suppressed.[3][4] He was almost unknown in the West until the early 1980s. Writing in The New York Times, Andrew Johnston praised Švankmajer's artistry, stating "while his films are rife with cultural and scientific allusions, his unusual imagery possesses an accessibility that feels anchored in the shared language of the subconscious, making his films equally rewarding to the culturally hyperliterate and to those who simply enjoy visual stimulation."[5]

Among his best known works are the feature films Alice (1988), Faust (1994), Conspirators of Pleasure (1996), Little Otik (2000) and Lunacy (2005), a surreal comic horror based on two works of Edgar Allan Poe and the life of Marquis de Sade. The two stories by Poe, "The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether" and "The Premature Burial", provide Lunacy its thematic focus, whereas the life of Marquis de Sade provides the film's blasphemy. His short film Dimensions of Dialogue (1982) was selected by Terry Gilliam as one of the ten best animated films of all time.[6] His films have been called "as emotionally haunting as Kafka's stories."[7] In 2010 he released Surviving Life, a live-action and cutout animation story about a married man who meets another woman in his dreams.

His most recent release is called Insects (Hmyz).[8] It had a projected budget of 40 million CZK, which was partially funded through an Indiegogo campaign which reached more than double its goal, and was released in January 2018.[8] The film is based on the play Pictures from the Insects' Life by Josef and Karel Čapek, which Švankmajer describes as following: "From the Life of Insects is a misanthropic play. My screenplay only extends this misanthropy, as man is more like an insect and this civilisation is more like an anthill. One should also remember the message in Kafka’s Metamorphosis."[9][8]

His life's works, inimitable style and voice have had far-reaching influences on the world of animation. Those whose work he has influenced include Brothers Quay, Caroline Leaf, Vera Neubauer, Terry Gilliam, Tomasz Bagiński, Nina Gantz and Phil Lord and Christopher Miller among many others.

He won the Golden Bear for Best Short Film at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1983 for Dimensions of Dialogue.

In 2000, Švankmajer received Lifetime Achievement Award at the World Festival of Animated Film - Animafest Zagreb.[10]

On 27 July 2013 he received the Innovation & Creativity Prize by Circolino dei Films, an independent Italian cultural organization.

On 10 July 2014, he received the 2014 FIAF Award during a special ceremony of the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival.

On 27 September 2018, he received the Raymond Roussel Society Medal in recognition of his extraordinary contribution: an inspiring, unique and universal work.

He was married to Eva Švankmajerová, an internationally known surrealist painter, ceramicist, and writer until her death in October 2005. Švankmajerová collaborated on several of her husband's movies, including Alice, Faust, and Otesánek. They had two children, Veronika (b. 1963) and Václav (b. 1975, an animator).

Filmography

Feature-length films

| Year | English title | Original title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | Alice | Něco z Alenky | Based on Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll |

| 1994 | Faust | Lekce Faust | Based on the Faust legend (including traditional Czech puppet show versions), Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, and Goethe's Faust. |

| 1996 | Conspirators of Pleasure | Spiklenci slasti | |

| 2000 | Little Otik | Otesánek | Based on Otesánek by Karel Jaromír Erben |

| 2005 | Lunacy | Šílení | Based on The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether and The Premature Burial by Edgar Allan Poe |

| 2010 | Surviving Life | Přežít svůj život | |

| 2018[11] | Insects | Hmyz | Based on Pictures from the Insects' Life by Karel Čapek and Josef Čapek |

| 2022 | The Kunstcamera | Kunstkamera | Documentary about the art and artifacts Svanmajer and his late wife have gathered over the years.[12][13] |

Short films

| Year | English title | Original title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | The Last Trick | Poslední trik pana Schwarcewalldea a pana Edgara | |

| 1965 | Johann Sebastian Bach: Fantasy in G minor | Johann Sebastian Bach: Fantasia G-moll | |

| 1965 | A Game with Stones | Spiel mit Steinen | |

| 1966 | Punch and Judy | Rakvičkárna | Also known as The Coffin Factory and The Lych House |

| 1966 | Et Cetera | ||

| 1967 | Historia Naturae (Suita) | ||

| 1968 | The Garden | Zahrada | |

| 1968 | The Flat | Byt | Available on the Little Otik DVD. Included in the Metropolitan Museum's "Surrealism Beyond Borders" exhibit (2021–22) |

| 1968 | Picnic with Weissmann | Picknick mit Weismann | |

| 1969 | A Quiet Week in the House | Tichý týden v domě | |

| 1970 | Don Juan | Don Šajn | |

| 1970 | The Ossuary | Kostnice | A documentary about the Sedlec Ossuary |

| 1971 | Jabberwocky | Žvahlav aneb šatičky slaměného Huberta | Based on Jabberwocky by Lewis Carroll |

| 1972 | Leonardo's Diary | Leonardův deník | |

| 1979 | Castle of Otranto | Otrantský zámek | Based on The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole |

| 1980 | The Fall of the House of Usher | Zánik domu Usherů | Based on The Fall of the House of Usher by Edgar Allan Poe |

| 1982 | Dimensions of Dialogue | Možnosti dialogu | |

| 1983 | Down to the Cellar | Do pivnice | |

| 1983 | The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope | Kyvadlo, jáma a naděje | Based on The Pit and the Pendulum by Edgar Allan Poe and A Torture by Hope by Auguste Villiers de L'Isle-Adam |

| 1988 | Virile Games | Mužné hry | Also known as The Male Game |

| 1988 | Another Kind of Love | Music video for Hugh Cornwell | |

| 1988 | Meat Love | Zamilované maso | |

| 1989 | Darkness/Light/Darkness | Tma, světlo, tma | |

| 1989 | Flora | ||

| 1989 | Animated Self-Portraits | Anthology film by 27 animators | |

| 1990 | The Death of Stalinism in Bohemia | Konec stalinismu v Čechách | |

| 1992 | Food | Jídlo | |

Animation and art direction

| Year | English title | Original title | Director |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | Dinner for Adele | Adéla ještě nevečeřela | Oldřich Lipský |

| 1981 | The Mysterious Castle in the Carpathians | Tajemství hradu v Karpatech | Oldřich Lipský |

| 1982 | Ferat Vampire | Upír z Feratu | Juraj Herz |

| 1983 | Visitors | Návštěvníci | Jindřich Polák |

| 1984 | Three Veterans | Tři veteráni | Oldřich Lipský |

Bibliography

- Peter Hames, Dark Alchemy: The Films of Jan Švankmajer. Westport: Praeger Publishers, 1995 ISBN 978-0275952990

- Eva Švankmajerová; Jan Švankmajer (1998). Anima Animus Animation - Evašvankmajerjan. Arbor vitae. ISBN 80-901964-4-6.

- Jan Švankmajer (2004). Transmutace smyslů / Transmutation of the Senses. Metrostav. ISBN 8090225837.

- Bertrand Schmitt, František Dryje, Švankmajer, Dimensions of dialogue. Between Film and Fine Art. Prague: Arbor Vitae, 2012 ISBN 978-8074670169

- Jan Švankmajer (2014). Touching and Imagining: An Introduction to Tactile Art. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781780761473.

See also

- Jiří Trnka, Czech animator and puppeteer

- Karel Zeman, Czech animator and filmmaker

- Jiří Barta, Czech stop motion animator

- Ladislaw Starewich, Polish animator and puppeteer

- The Torchbearer, a film by Jan Švankmajer's son, Václav

- List of stop motion films

References

- ↑ Solomon, Charles (19 July 1991). "Brooding Cartoons From Jan Svankmajer". LA Times. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films. BFI Booklet.

- ↑ Siegal, Nina (20 December 2018). "The 'Godfather of Animated Cinema' Makes More Than Just Movies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ↑ Jones, Jonathan (5 December 2011). "Jan Svankmajer: Puppets and politics". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ↑ New York Times ,1 July 2001

- ↑ Gilliam, Terry (27 April 2001). "Terry Gilliam Picks the Ten Best Animated Films of All Time". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Review/Film; A Mutant Tom Thumb Born Outside Time". NY Times. 1994.

- 1 2 3 "Insects (2017)". FilmAffinity. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ↑ "Jan Švankmajer readies a new feature". Cineuropa. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ↑ "Animafest Zagreb 2000".

- ↑ "Producent Kallista dostal miliony na nový film Jana Švankmajera". Borovan.cz. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Czech surrealist maestro Jan Švankmajer has completed his last feature-length documentary, Kunstkamera". Cineuropa - the best of european cinema. 25 July 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ↑ info(at)s2studio.cz, S2 STUDIO s r o-INTERNETOVÉ SLUŽBY, GRAFIKA, VÝROBA REKLAMY, MARKETING, https://www s2studio cz. "MFDF Ji.hlava". www.ji-hlava.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 25 November 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Peter Hames (1995). Dark Alchemy: The Films of Jan Svankmajer. Praeger Paperback. ISBN 0-275-95299-1.

- Peter Hames (2007). The Cinema of Jan Svankmajer: Dark Alchemy (Directors' Cuts). Wallflower Press. ISBN 978-1905674459.

- Bertrand Schmitt; František Dryje, eds. (2012). Jan Švankmajer. Dimensions of Dialogue / Between Film and Fine Art. Arbor vitae. ISBN 978-80-7467-016-9.

- Michael Richardson (2006). "Jan Svankmajer and the Life of Objects". Surrealism and Cinema. New York: Oxford UP. ISBN 9781845202262.

- Keith Leslie Johnson (2017). Jan Švankmajer: Animist Cinema. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252083020.

External links

- Jan Švankmajer at IMDb

- The Animation of Jan Svankmajer at Keyframe - the Animation Resource

- Overview of his work

- Jan Švankmajer - PL (in Polish)

- On Svankmajer's Faust

- The Works of Jan Svankmajer

- Downing the Folk-Festive: Menacing Meals in the Films of Jan Svankmajer

- Czech Animation, private blog

- An article and filmography on Svankmajer

- Review of Dimensions of Dialogue, The Ossuary, Food and Death of Stalinism