| 1944 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | July 13, 1944 |

| Last system dissipated | November 14, 1944 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | "Great Atlantic" |

| • Maximum winds | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 918 mbar (hPa; 27.11 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 21 |

| Total storms | 14 |

| Hurricanes | 8 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 1,025-1,125 |

| Total damage | $202 million (1944 USD) |

| Related articles | |

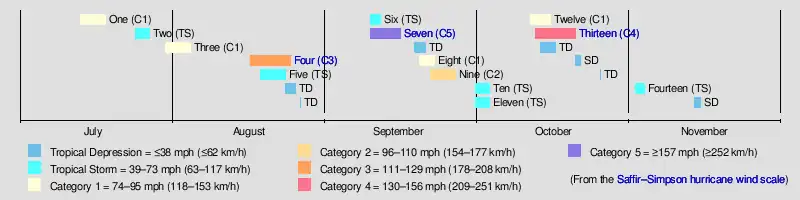

The 1944 Atlantic hurricane season featured the first instance of upper-tropospheric observations from radiosonde – a telemetry device used to record weather data in the atmosphere – being incorporated into tropical cyclone track forecasting for a fully developed hurricane. The season officially began on June 15, 1944, and ended on November 15, 1944. These dates describe the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. The season's first cyclone developed on July 13, while the final system became an extratropical cyclone by November 13. The season was fairly active season, with 14 tropical storms, 8 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes.[nb 1] In real-time, forecasters at the Weather Bureau tracked eleven tropical storms, but later analysis uncovered evidence of three previously unclassified tropical storms.

The strongest storm of the season was the Great Atlantic hurricane,[nb 2] which struck Long Island and New England and later Atlantic Canada after becoming extratropical, causing about $100 million (1944 USD)[nb 3] in damage across the East Coast of the United States and Atlantic Canada, as well as at least 391 deaths, most of which occurred at sea. The Jamaica hurricane and Cuba–Florida hurricane were also powerful and left major impacts. The former inflicted "several millions of dollars" in damage in Jamaica, while 116 deaths were recorded throughout its path. The Cuba–Florida hurricane devastated both regions, resulting in at least 318 fatalities and damage exceeding $100 million. A hurricane which struck Mexico in late September caused between 200 and 300 deaths in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec due to flooding. Collectively, the tropical cyclones during the 1944 season caused about $202 million in damage and at least 1,025 fatalities.

Seasonal summary

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 15 and ended on November 15.[4] A total of 21 tropical cyclones developed.[2] Fourteen of those cyclone intensified into tropical storms, the most since 1936, while eight of those reached hurricane status, the highest number since 1933. Three of those hurricanes intensified into major hurricanes.[1] The season included the first instance of upper-atmosphere data via radiosonde being successfully incorporated into tropical cyclone track forecasting for a fully developed hurricane, which occurred as the Cuba–Florida hurricane approached Cuba.[5] Collectively, the tropical cyclones of the 1944 Atlantic hurricane season caused approximately $202 million in damage and at least 1,025 fatalities.[6][7][8][9]

Tropical cyclogenesis is believed to have begun with Hurricane One on July 13. Two other tropical cyclones formed in July.[2] Four systems developed in August, two tropical depressions, a tropical storm, and a hurricane – the Jamaica hurricane. The month of September featured the most activity, which included a tropical depression, three tropical storms, and three hurricanes. One of the hurricanes, the Great Atlantic hurricane, became the most intense tropical cyclone of the season, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 918 mbar (27.1 inHg). During October, a subtropical depression, two tropical depressions, and two hurricanes developed. November featured a tropical storm and a subtropical depression, the latter of which was absorbed by a frontal system on November 14, marking the conclusion of cyclonic activity for the season.[10]

The season's total activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 104, the highest total since 1935. ACE is a measure of the power of a tropical storm multiplied by the length of time it existed. Therefore, a storm with a longer duration will have high values of ACE. It is only calculated at six-hour increments in which specific tropical and subtropical systems are either at or above sustained wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm intensity. Thus, tropical depressions are not included here.[1]

Systems

Hurricane One

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 13 – July 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 995 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave was noted near Grenada on July 11;[6] it organized into the season's first tropical depression two days later around 06:00 UTC while situated near Navidad Bank in the Turks and Caicos Islands.[2] Upon designation, the Weather Bureau planned reconnaissance flights for the first time ever to fly into a newly formed cyclone.[6] It intensified as it moved northwest, attaining tropical storm intensity by 00:00 UTC on July 14 and further strengthening into the season's first hurricane around 06:00 UTC on July 16. After reaching peak winds of 80 mph (130 km/h),[2] the hurricane recurved toward the northeast and began to weaken, though Bermuda reported winds near 40 mph (64 km/h) upon the storm's closest approach.[6] It transitioned into an extratropical cyclone around 00:00 UTC on July 19 and continued into the northern Atlantic, where it was absorbed by a larger extratropical low southeast of Newfoundland the next day.[2][10]

Tropical Storm Two

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 24 – July 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 999 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave organized into a tropical storm east of Barbados around 06:00 UTC on July 24, although it is possible the system existed farther east in the absence of widespread observations. The system passed near Martinique,[2] where Fort-de-France recorded sustained winds up to 55 mph (89 km/h),[6] before continuing on a west-northwest course through the Caribbean Sea. Though it was initially believed the storm struck Haiti, where considerable damage was reported along the coastline near Port-au-Prince, and ultimately deteriorated, modern reanalysis suggests the cyclone continued south of the island. The system was then intercepted by strong wind shear that led to its dissipation west-southwest of Jamaica by 18:00 UTC on July 27. Its remnants continued westward and were last reported north of Honduras the following day.[2][10]

Hurricane Three

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 30 – August 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 985 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave organized into a tropical storm about 135 mi (217 km) east of Cockburn Town in the Turks and Caicos Islands around 12:00 UTC on July 30.[6] The newly formed system intensified on a west-northwest course parallel to the Bahamas, attaining hurricane strength by 00:00 UTC on August 1. From there, it curved toward the north before making landfall on Oak Island, North Carolina, with peak winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) at 23:00 UTC. The system weakened as it progressed through the Mid-Atlantic and into the northwestern Atlantic, and it was last considered a tropical depression around 06:00 UTC on August 4 about 105 mi (169 km) east of Nantucket.[2]

Despite the storm's small size, it produced wind gusts of 72 mph (116 km/h) in Wilmington, North Carolina, where the hurricane unroofed many houses, felled communication lines, shattered glass windows, and uprooted hundreds of trees. Throughout Carolina Beach and Wrightsville Beach, an unusually high tide—combined with waves perhaps as large as 30 ft (9.1 m)—demolished several cottages and homes, or otherwise swept the structures off their foundations. The former city suffered a disastrous hit as its boardwalk was destroyed, while in Wrightsville Beach, local police estimated that the water reached 18 ft (5.5 m) by its city hall. Two fishing piers were destroyed in each city.[10] Crops sustained catastrophic loss throughout coastal beach counties. Rainfall was moderate, reaching 3–5 in (76–127 mm) across eastern North Carolina, with a maximum storm-total amount of 7.7 in (200 mm) in Cheltenham, Maryland.[11] Damage reached $2 million. As the cyclone exited into the Atlantic, it produced a gust of 38 mph (61 km/h) in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Though no fatalities occurred along the storm's path due to mass evacuations,[6] there were a few people who suffered serious injuries.[10]

Hurricane Four

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 16 – August 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); ≤973 mbar (hPa) |

The fourth cyclone of the season was first noted as a strong tropical storm east of Barbados around 18:00 UTC on August 16.[6] The small storm passed over Grenada and into the eastern Caribbean Sea, where it quickly intensified into a hurricane. On a west-northwest course, the system organized into the season's first Category 3 major hurricane around 12:00 UTC on August 19, attaining peak winds of 120 mph (190 km/h) six hours later. The hurricane grazed the northern coastline of Jamaica and continued westward while weakening slightly. The cyclone made a second landfall near Playa del Carmen on the Yucatán Peninsula with winds of 90 mph (140 km/h) early on August 22. The cyclone entered the Bay of Campeche as a strong tropical storm weakened to sustained winds of 40 mph (64 km/h) before moving ashore just north of Tecolutla, Veracruz. Then, it quickly dissipated by 12:00 UTC on August 24.[2]

As the cyclone entered the Caribbean, it intercepted a British vessel which then went missing, with all 74 passengers aboard presumed dead. Across Jamaica, numerous buildings were heavily damaged, including light-frame dwellings that were blown down or crushed under fallen trees. Significant crop loss was observed, with 41% of coconut trees and 90% of banana trees destroyed; in some cases, every tree fell over in the coconut plantations. Two railway vans, each weighing 14.5 t (29,000 lbs), were overturned; as such, it was estimated that gusts reached 100–120 mph (160–190 km/h) along the northeastern coastline. At least 30 people were killed across the island. In the Cayman Islands, wind gusts topped 80 mph (130 km/h), though no damage was reported.[10] Overall, the storm killed at least 116 people.[6]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 18 – August 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave was first noted passing through the Windward Islands on August 13.[10] Trekking through the Caribbean Sea, the system coalesced into a tropical depression about 115 mi (185 km) east of the Isla de Cozumel by 12:00 UTC on August 18. Narrowly missing the Yucatán Peninsula, the system continued west-northwest into the central Gulf of Mexico, where it attained tropical storm intensity by 18:00 UTC on August 19 and reached peak winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) on August 21. The system moved ashore northeast of San Fernando, Tamaulipas, with slightly weaker winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) before progressing inland and dissipating by 06:00 UTC on August 23.[2] Little impact was noted from the cyclone, with an observation station in northeastern Nuevo León recording a wind gust of only 17 mph (27 km/h). However, the storm did produce a maximum gust of 45 mph (72 km/h) in Brownsville, Texas.[10] Rainfall in the Rio Grande Valley was mostly beneficial due to drought conditions.[12]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 9 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 992 mbar (hPa) |

On September 8, a weak area of low pressure developed along the tail-end of a stationary front across the northern Gulf of Mexico.[10] It quickly organized into a tropical depression by 00:00 UTC the next day, positioned about 170 mi (270 km) southeast of Matamoros, Tamaulipas, and further attained tropical storm intensity twelve hours later. The fledgling system moved north and then northeast, making its first landfall along the Mississippi River Delta with peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) around 19:00 UTC on September 10. The system made its second landfall along Dauphin Island, Alabama, at 23:00 UTC at a slightly reduced intensity. It dissipated by 12:00 UTC on September 11 and was last documented about 40 mi (64 km) southwest of Montgomery, Alabama.[2]

As the cyclone moved ashore, Mobile, Alabama, recorded its highest 24-hour rainfall total – 7.04 in (179 mm) – since 1937. The streets of the city were inundated by flood waters, sustaining considerable damage alongside bridges. The Mobile River reached a height of 3.8 ft (1.2 m) above sea level, its highest crest since 1932. Pensacola, Florida, recorded sustained winds of 54 mph (87 km/h) that resulted in about $500 worth of damage from damaged dwelling roofs. Tides peaked around 1 ft (0.30 m).[10]

Hurricane Seven

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 9 – September 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min); 918 mbar (hPa) |

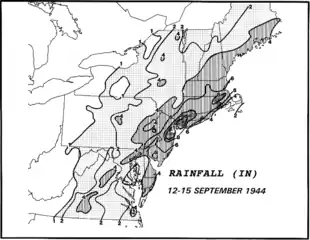

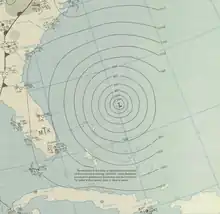

Observations from a reconnaissance aircraft flight indicated that a tropical wave had developed into a tropical cyclone on September 9 about 300 mi (485 km) northeast of the Lesser Antilles.[10] Already at tropical storm intensity, the system strengthened into a Category 1 hurricane about 24 hours later as it tracked west-northwestward. The storm intensified further, reaching major hurricane status early on September 12. Several hours later, the storm strengthened into a Category 5 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale. The hurricane then curved north-northwestward on September 13.[2] That day, the crew of the USS Alacrity near the hurricane – then centered northeast of the Bahamas – observed a barometric pressure of 918 mbar (27.1 inHg), the lowest in association to the storm. Based on the pressure-wind relationship, sustained wind speeds likely peaked at 160 mph (260 km/h).[10] Early on September 14, the hurricane weakened to a to Category 3 intensity, several hours before passing just offshore North Carolina. The cyclone weakened further to a Category 2 prior to making landfall near East Hampton, New York, around 02:00 UTC on September 15 and near Charlestown, Rhode Island, about two hours later. The storm emerged into the Gulf of Maine and then transitioned into an extratropical cyclone near Mount Desert Island, Maine. The extratropical remnants continued east-northeastward across Atlantic Canada before dissipating over the far north Atlantic on September 16.[2]

The cyclone produced hurricane-force winds along the East Coast of the United States from North Carolina to Massachusetts. Sustained winds in North Carolina peaked at 110 mph (180 km/h) at Hatteras. Across the state, the hurricane damaged 316 homes and destroyed 28 others, while 351 buildings were damaged and 80 others were destroyed. In Virginia, Cape Henry recorded a sustained wind of 134 mph (216 km/h),[7] which is Category 4 intensity. However, the sustained wind speed was recorded at a 30-second duration, rather than 1-minute, while the anemometer height was about 52 ft (16 m) above ground. Instead, the state likely experienced sustained winds up to Category 2 intensity.[10] Throughout Virginia, 1,350 homes suffered some degree of damage, while 782 buildings were damaged and 31 others were demolished. In Maryland, the storm damaged 650 homes, while the cyclone also damaged 300 buildings and destroyed 15 others. The storm damaged about 1,800 homes and 850 buildings in Delaware. New Jersey that experienced the most damages from the hurricane, especially due to storm surge and sustained winds up to 91 mph (146 km/h) in Atlantic City. Throughout the state, the cyclone demolished 463 homes and 217 buildings, while damaging 3,066 other homes and 635 other buildings. The storm produced hurricane-force winds in coastal New York, including in New York City, as well as waves up to 6.4 ft (2.0 m) above mean low tide. A total 117 homes and 272 buildings were destroyed and 2,427 homes and 852 suffered some degree of structural impact. In Connecticut, the hurricane demolished 60 residences and 500 buildings, while causing damage to 5,136 dwellings and 4,550 other structures. Rhode Island observed hurricane-force winds and tides up to 12 ft (3.7 m) above mean low tide at the city of Providence. Within the state, the cyclone wrecked 23 homes and 368 buildings and damaged 5,525 homes and 7,597 buildings. Massachusetts reported similar conditions, especially near the coast. The hurricane destroyed 230 homes and 158 buildings and inflicted some degree of damage to 3,898 homes and 915 buildings. Overall, the hurricane caused about $100 million in damage and 46 deaths on land in the United States. Additionally, at least 344 people were killed at sea due to maritime incidents relating to the storm. The largest number of deaths occurred when the USS Warrington sunk about 450 mi (725 km) east of Vero Beach, Florida, leading to the deaths of 248 sailors.[7] In Canada, the Atlantic provinces reported some wind damage to buildings, homes, and trees, as well as power outages. One person died in Nova Scotia due to electrocution.[8]

Hurricane Eight

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 19 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave led to the formation of another tropical storm over the northwestern Caribbean Sea around 06:00 UTC on September 19.[6] It moved northwest after formation while steadily intensifying, attaining hurricane strength by 00:00 UTC the next day. The storm moved ashore near Cancún, Quintana Roo, with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). After moving inland, the cyclone weakened to a tropical storm and curved southwestward. After emerging into the Bay of Campeche early on September 21, it re-attained peak winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) and made a second landfall near Paraíso, Tabasco. The cyclone turned south over the mountainous terrain of Mexico,[10] dissipating after 12:00 UTC on September 22.[2]

At least two people drowned offshore Campeche, when a 100-ton (91,000 kg)-schooner sank. The hurricane produced torrential rainfall in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region of Mexico, causing severe flooding. Between 200 and 300 people drowned,[6] while survivors sought refuge in trees and atop roofs and boxcars. Aircraft and boats conducted search and rescue operations throughout the region.[13] Floods also wrought extensive damage to the communication and transportation systems.[6]

Hurricane Nine

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 21 – September 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); ≤995 mbar (hPa) |

The ninth storm of the season formed early on September 21, via a tropical wave that departed the western coast of Africa several days prior.[2][10] The cyclone only slowly organized as it tracked west-northwest and then north, attaining hurricane strength early on September 24. After reaching its peak as a Category 2 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) around 12:00 UTC the next day, an approaching cold front prompted the beginning of extratropical transition. The hurricane became extratropical on September 26, well south of Newfoundland. The post-tropical cyclone curved northeast over the far northern Atlantic and was last noted south of Iceland two days later.[2]

Tropical Storm Ten

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 30 – October 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

On September 28, a broad area of low pressure developed adjacent to a dissipating warm front over the north-central Atlantic.[10] The cyclone congealed over the next two days and attained tropical storm status by 00:00 UTC on September 30,[2] which was confirmed by a nearby ship report.[10] It slowly intensified on a north and then northeast course, peaking with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) early on October 1. The system weakened to a tropical depression the following day and was subsequently absorbed by an approaching extratropical cyclone by 00:00 UTC on October 3.[2]

Tropical Storm Eleven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 30 – October 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); |

The eleventh tropical storm of the season was first detected about 80 mi (130 km) north of Barbados around 06:00 UTC on September 30, as indicated by many ship and land observations. The short-lived cyclone moved northwest and then north ahead of an approaching trough, acquiring peak winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) shortly after formation before presumably dissipating on October 3. Alternatively, in the absence of widespread observations, the system may have continued into the central Atlantic unnoticed.[2][10]

Hurricane Twelve

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 11 – October 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

On the second week of October, a broad area of low pressure began to take shape along a frontal boundary across the northeastern Atlantic. The system steadily acquired tropical characteristics,[10] and it was designated as a tropical storm by 00:00 UTC on October 11 while located about 570 mi (920 km) west-southwest of the Azores. It moved very slowly east and then northeast, attaining hurricane intensity and peaking with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) on October 12. The cyclone resumed its eastward motion shortly thereafter and weakened below hurricane strength, passing north of the Azores before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone early on October 15.[2] The post-tropical storm tracked east-southeast into Portugal and Spain, where a sustained wind speed of 46 mph (74 km/h) was recorded in Seville.[10]

Hurricane Thirteen

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 12 – October 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min); 937 mbar (hPa) |

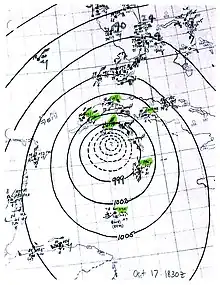

On October 12, a disturbance in the western Caribbean Sea organized into a tropical depression near the Swan Islands.[9][10] The system quickly strengthened as it drifted towards the north, becoming a hurricane the following day. After turning towards the west, it passed south of Grand Cayman and then resumed an accelerated northward motion near the 83rd meridian west between October 16–17.[2][10] The hurricane intensified significantly during this period, quickly attaining Category 4 intensity before reaching its peak strength with winds of 145 mph (233 km/h) on October 18. The storm made landfalls over Isla de la Juventud and the Cuban mainland at peak intensity later that day,[2] passing 10–15 mi (16–24 km) west of Havana.[9] The storm weakened after crossing Cuba, but was unusually large, with strong winds extending from 200 mi (320 km) east of the center to 100 mi (160 km) west of the center.[10] Its center passed over the Dry Tortugas as a major hurricane late on October 18, before striking Sarasota, Florida, the following morning with winds of 105 mph (169 km/h).[10] The storm weakened slowly over the Florida Peninsula, and the system eventually transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over South Carolina on October 20. The extratropical remnants moved northward, before merging with the Icelandic Low near Greenland.[9][10]

The hurricane proved to be an important test of the American radiosonde network, whose upper-atmosphere data were successfully incorporated into tropical cyclone track forecasting, the first such instance on record.[5] Squally conditions battered the Cayman Islands for three days, destroying every crop on the islands;[14] the 31.29 in (795 mm) of rain recorded on Grand Cayman was the highest in the island's history.[15][16] At least 300 people were killed in Cuba, though the full extent of casualties remains unknown as reports from rural areas of the island were never compiled.[9] In Havana, numerous buildings were damaged.[17] A weather station in Havana documented a 163 mph (262 km/h) wind gust, which stood as the strongest gust measured in the country until Hurricane Gustav in 2008.[18] Crops suffered extensively, exacerbated by the hurricane's timing near optimal harvest time.[19] Total damage in the state amounted to $63 million,[9] with about $50 million attributed to crop damage.[19] Eighteen deaths were reported in the state and 24 others were hospitalized.[9] Heavy rains and gusty winds were felt throughout the Eastern Seaboard from the hurricane and its extratropical remnants,[11][20] causing widespread power outages. Overall, the hurricane caused more than $100 million in damage and at least 318 fatalities.[9]

Tropical Storm Fourteen

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 1 – November 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression formed about 35 mi (56 km) southeast of San Andrés around 00:00 UTC on November 1. Moving slowly southwestward, the depression attained tropical storm intensity six hours later and further intensified to attain peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) early the next day.[2] Because there were few ship and land observations; however, it is possible the storm became a hurricane, with historical precedence in Hurricane Martha.[10] It then weakened, turned eastward, and dissipated on November 3 without moving ashore.[2]

Tropical depressions

In addition to the fourteen tropical cyclones that reached at least tropical storm intensity,[2] seven others did not strengthen beyond tropical depression status. The first such system developed just west of Bermuda on August 23. Moving rapidly northeastward, the depression would be absorbed by a frontal system near Nova Scotia two days later. Another depression developed from a tropical wave over the southeast Caribbean Sea near the Windward Islands on August 26. The depression moved westward and is believed to have dissipated quickly, though this might be due to a lack of observations. On September 18, a reconnaissance aircraft flight confirmed the development of a tropical depression over the northeastern Caribbean. The depression moved northwestward, crossing the Virgin Islands on the following day. After entering the open Atlantic north of the islands, the depression dissipated east of the Turks and Caicos Islands on September 21.[10]

Weather maps and data indicate that a tropical depression formed just east of the Lesser Antilles on October 13. The depression entered the Caribbean and later crossed the Mona Passage, a strait between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, on October 15. By the following day, the depression dissipated near the southeastern Bahamas. A frontal low-pressure area developed into a subtropical depression on October 20, far to the southwest of the Azores. The subtropical depression moved slowly northward and dissipated by the following day. On October 25, a tropical depression formed over the northwestern Caribbean. Dissipation likely occurred on the next day. The next cyclone, and the final system of the 1944 Atlantic hurricane season, developed from a frontal low east-northeast of Bermuda on November 13. A frontal system absorbed the subtropical depression on the following day.[10]

Season effects

This is a table of all the storms that have formed in the 1944 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s), denoted in parentheses, damage, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in 1944 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | July 13 – 18 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 995 | Turks and Caicos Islands, the Bahamas, Bermuda | None | None | |||

| Two | July 24 – 27 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 999 | Windward Islands, Haiti | None | None | |||

| Three | July 30 – August 4 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 985 | Turks and Caicos Islands, the Bahamas, North Carolina, Mid-Atlantic region | $2 million[6] | None | |||

| Four | August 16 – 24 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 (195) | ≤973 | Windward Islands, Greater Antilles, Mexico, Texas | Unknown | 116[6] | |||

| Five | August 18 – 23 | Tropical storm | 64 (95) | 1007 | Mexico, Texas | Unknown | None | |||

| Depression | August 23 – 25 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Depression | August 26 – 26 | Tropical depression | Unknown | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Six | September 9 – 11 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 992 | Gulf Coast of the United States | $500[10] | None | |||

| Seven | September 9 – 15 | Category 5 hurricane | 160 (260) | 918 | North Carolina, Mid-Atlantic region, New England, Atlantic Canada | $100 million[7] | 391[7][8] | |||

| Depression | September 18 – 21 | Tropical depression | Unknown | 1009 | Virgin Islands | None | None | |||

| Eight | September 19 – 22 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 996 | Mexico | Unknown | 200-300[6] | |||

| Nine | September 21 – 26 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | ≤995 | None | None | None | |||

| Ten | September 30 – October 2 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1003 | None | None | None | |||

| Eleven | September 30 – October 3 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | Unknown | Leeward Islands | None | None | |||

| Twelve | October 11 – 15 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 998 | None | None | None | |||

| Thirteen | October 12 – 24 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 937 | Swan Islands, Cayman Islands, Cuba, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada | $100 million[9] | 318[9] | |||

| Depression | October 13 – 16 | Tropical depression | Unknown | 1008 | Lesser Antilles | None | None | |||

| Subtropical depression | October 20 – 21 | Tropical depression | 30 (55) | 1003 | None | None | None | |||

| Depression | October 25 – 26 | Tropical depression | 25 (35) | 1008 | None | None | None | |||

| Fourteen | November 1 – 3 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 1002 | None | None | None | |||

| Subtropical depression | November 13 – 14 | Tropical depression | Unknown | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 21 systems | July 13 – November 14 |

145 (230) | 933 | $202 million | 1,025-1,125 | |||||

See also

Notes

- ↑ A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[1]

- ↑ Prior to the beginning of the practice of officially naming tropical cyclones in 1950, tropical cyclones listed in the Atlantic hurricane database are identified by number,[2] while some notable storms, such as the Great Atlantic hurricane, are also referred to by nicknames.[3]

- ↑ All damage figures are in 1944 USD, unless otherwise noted

References

- 1 2 3 "Atlantic Basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". Hurricane Research Division. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. June 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Continental United States Hurricane Impacts/Landfalls 1851-2019 (Report). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. June 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ↑ "Forecasters Prepare For Tropical Storms". Miami Herald. No. 191. Miami, Florida. June 11, 1944. p. 8-B. Retrieved February 17, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Rappaport, Edward N.; Simpson, Robert H. (January 1, 2003). "Impact of Technologies from Two World Wars". In Simpson, Robert H.; Anthes, Richard; Garstang, Michael; Simpson, Joanne (eds.). Hurricane! Coping with disaster: Progress and Challenges Since Galveston, 1900. Washington, D.C.: American Geophysical Union. pp. 49–50. doi:10.1029/SP055. ISBN 9780875902975. (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Woolard, Edgar W. (December 1944). "Monthly Weather Review: North Atlantic Hurricanes and Tropical Disturbances of 1944" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 Sumner, H. C. (September 1944). Woolward, Edgar W. (ed.). "The North Atlantic Hurricane Of September 8–14, 1944" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 72 (9): 187–189. Bibcode:1944MWRv...72..187S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1944)072<0187:TNAHOS>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- 1 2 3 1944-7 (Report). Environment Canada. November 7, 2009. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sumner, H. C. (November 1944). "The North Atlantic Hurricane of October 13–21, 1944" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 72 (11): 221–223. Bibcode:1944MWRv...72..221S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1944)072<0221:TNAHOO>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2017. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Landsea, Christopher W.; et al. "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- 1 2 Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (PDF) (Report). Weather Prediction Center. July 1956. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- ↑ "Hurricane Veers Into Campeche, Perils Mexico". The Brownsville Herald. No. 44. Brownsville, Texas. August 23, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved February 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "All Types of Craft Rushed to Rescue of Mexico Flood Victims". Iowa City Press-Citizen. Iowa City, Iowa. Associated Press. October 2, 1944. p. 8. Retrieved February 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Cayman Crops Destroyed". The Gazette. No. 155. Montreal, Quebec. The Canadian Press. October 18, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved May 11, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Barnes, Jay (May 2007). "Hurricanes in the Sunshine State, 1900–1949". Florida's hurricane history (2nd ed.). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 163–166. ISBN 9780807858097.

- ↑ Roth, David M. (May 26, 2009). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall" (PowerPoint Presentation). Camp Springs, Maryland: Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on May 31, 2017. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ↑ "Six Killed, Damage Heavy as Hurricane Rips Havana". St. Petersburg Times. No. 87. St. Petersburg, Florida. Associated Press. October 19, 1944. p. 11. Retrieved June 23, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Rubiera, José (October 8, 2014). "Crónica del Tiempo: Los huracanes y octubre". CubaDebate (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: Universidad de las Ciencias Informáticas. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- 1 2 Bennett, W. J. (October 1944). "Florida Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Jacksonville, Florida: National Climatic Data Center. 48 (10): 55. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ↑ "Hurricane Lashes South Carolina, Moves On". St. Petersburg Times. No. 88. St. Petersburg, Florida. Associated Press. October 20, 1944. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved June 24, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.