Henri L'Estrange | |

|---|---|

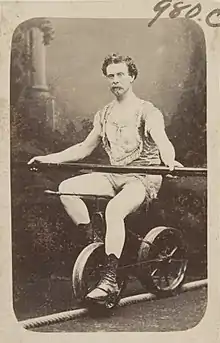

Studio portrait of Henri, 1876 | |

| Born | c. 1842 |

| Died | after 1894 |

| Other names | The Australian Blondin |

| Occupation | Performer |

| Known for | Funambulist, Balloonist |

Henri L'Estrange, known as the Australian Blondin, was an Australian successful funambulist and accident-prone aeronautical balloonist.[1] Modelling himself on the famous French wire-walker Charles Blondin, L'Estrange performed a number of tightrope walks in the 1870s, culminating in three walks across Sydney's Middle Harbour in 1877. He remains the only tightrope performer ever to have walked across a part of Sydney Harbour.[1]

L'Estrange was an early balloonist, and attempted a series of flights in the early 1880s – one being successful, one ending in Australia's first emergency parachute descent, and the last culminating in a massive fireball causing property damage, personal injury and a human stampede. He tried to return to his original career of tightrope walking but, with new forms of entertainment, humiliating falls and other Blondin imitators, he found success elusive. Public benefits were held in his honour to recoup financial losses and he dabbled in setting up amusement rides but ultimately he faded from public attention and was last recorded to be living in Fitzroy, Victoria in 1894.

Early life

Henri L'Estrange was born about 1842 in Fitzroy, a suburb of Melbourne.[2] Little is known of his early years, family or private life.

Early performances

He first came to public attention in 1873 as a member of a Melbourne performance group, the Royal Comet Variety Troupe, a gymnastic, dancing and comedic vocal combination with Miss Lulu L'Estrange and Monsieur Julian. As part of this troupe, L'Estrange performed in Melbourne and Tasmania throughout 1873 and 1874, with Henri and Lulu performing together on the tightrope.[3] In 1876, L'Estrange performed solo for the first time in Melbourne, and quickly gained a reputation as a fearless performer.

Tightrope walking had grown in popularity in Australia through the 1860s, following reports reaching the Australian Colonies of the exploits of the great French walker, Charles Blondin, who crossed Niagara Falls in 1859. By the mid-1860s, Australian wire walkers (funambulists) were modelling themselves on Blondin, copying his techniques, with several even calling themselves "the Australian Blondin". The popularity of the name surged after the original Blondin visited Australia in 1874, performing his highwire act in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. By the mid-1880s, there were at least five "Blondins" performing regularly in Sydney and elsewhere.

L'Estrange began using the moniker "the Australian Blondin" from early 1876. Arriving in Sydney from Melbourne, L'Estrange erected a large canvas enclosure in The Domain and began a regular series of performances on the tightrope, copying the location and stunts of the real Blondin who had performed there in August 1874.[4] His opening night on 26 January 1877 attracted a reported crowd of between two and three thousand people. Newspaper reports commented that his performance was so like that of the original Blondin that people could be forgiven for thinking they had seen the world-renowned rope-walker. With his rope suspended 40 feet (12 metres) above the ground, L'Estrange walked backwards and forwards, walked in armour, walked covered in a sack, used and sat on a chair, cooked and rode a bicycle, all on the rope. His show also included a fireworks display for the public's entertainment.[5]

L'Estrange performed in the Domain from January through to April 1877, but not without incident. On 7 February 1877, as L'Estrange neared the end of his wire act, sparks from the fireworks going off around him fell into the nearby store of gunpowder and fireworks, igniting them. The store's shed was demolished, a surrounding fence knocked down, part of L'Estrange's performance tent caught fire, and two young boys were injured.[1]

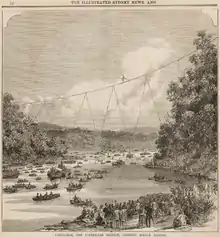

Sydney Harbour crossing

In late March 1877, advertisements began to appear in the Sydney newspapers for L'Estrange's proposed harbour crossing. The first public performance was set for Saturday 31 March, with L'Estrange having organised 21 steamers to convey spectators from Circular Quay to a special landing stage close to his performance area. L'Estrange advised those wishing to see his performance to travel on his steamers as they were the only ones with permission to land passengers. This, of course this did not stop other entrepreneurs and captains from carrying spectators of their own.[2] Whilst the event was profitable L'Estrange considered that the majority of viewers were non-paying "dead-heads".[6]

Prior to the public performance, L'Estrange undertook the crossing for a select audience including members of the press. That crossing was a success, and was well reviewed in the papers, no doubt adding to the crowd's anticipation for the Saturday show.[7] Bad weather postponed the performance, which did not go ahead until 14 April.[2][8]

At 1 o'clock on Saturday 14 April, the steamers began leaving Circular Quay, conveying 8,000 of an estimated 10,000-strong crowd to Middle Harbour – a large crowd considering the alternative attractions that day of Sydney Royal Easter Show (known then simply as "the Exhibition") and horse racing.[2] The remainder were reported to be walking from St Leonards, with a toll being collected along the way. Spectators clambered up the sides of the bay for vantage points, while hundreds more stayed on board steamboats, yachts and in row boats below.[2] The rope was strung across the entrance to Willoughby Bay, from Folly Point to the head of the bay, a reported length of 1,420 feet (430 m), 340 feet (100 m) above the waters below.[7] The distance meant that two ropes were required, spliced together in the centre, to reach the other side, with 16 stays fixed to the shore and into the harbour to steady the structure.

Everything being ready, precisely at 4 o'clock L'Estrange come out of his tent on the eastern shore, dressed in a dark tunic and a red cap and turban. Without hesitation or delay he stepped onto the narrow rope, and, with his heavy balancing-pole, at once set out on his journey across the lofty pathway. As has been before stated, the rope is stretched across the harbour at a great altitude, the width apparently being three hundred yards. At the western end it is higher than at the eastern, and as the weight of the rope causes a dip in the centre, the western end is at a considerable incline. Starting off amidst the cheers of the spectators, L'Estrange walked fearlessly at the rate of eighty steps to a minute across the rope, until he reached a spliced part near the centre, some twenty feet in length, which he passed more deliberately. Then he stood on his right foot, with his left resting against his right leg. This feat being safely accomplished, he dropped onto his knee, and afterwards sat down and waived [sic] his handkerchief to the crowd of spectator. Next he lay on his back along the rope. Resuming the sitting posture, he took out a small telescope and for a moment or two surveyed the onlookers, who warmly applauded his performances. Raising the balancing pole, he lifted one foot onto the rope, then the other, and continued his walk. He took a few steps backward and then proceeded up the inclined part of the rope steadily to the western shore, at the slower speed of about sixty steps a minute, the rope swaying considerably as he went. The remaining part of the distance was safely traversed, the last few steps being walked more quickly: and the intrepid performer stepped on terra firma amidst the enthusiastic cheers of the spectators, the inspiring strains of the bands of music, and the shrill whistling of the steamers.

— The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 April[2] and 4 May 1877

The successful crossing was greeted with enthusiastic cheers, the tunes of the Young Australian Band, the Albion Brass Band and Cooper and Bailey's International Show Band, who had all come to entertain the crowds, and the shrilling of the steamers' whistles. L'Estrange soon reappeared in a small row boat to greet the crowds, although many had already rushed the steamers to leave, resulting in a few being jostled into the harbour.[2]

While the Illustrated Sydney News proclaimed it a truly wonderful feat, performed with the greatest coolness and consummate ability, not all of Sydney's press were so enthusiastic. The Sydney Mail questioned the worth of such a performance beyond the profits made, commenting that it was, "...a mystery to many minds why such large concourses of people should gather together to witness a spectacle which has so little intrinsic merit. There is nothing about it to charm the taste or delight the fancy."[9]

Despite the criticism, L'Estrange performed at least once more at Middle Harbour, although crowds were down to a few hundred, requiring only four steamers to transport them. The same night he was guest of honour at a testimonial dinner held at the Victoria Theatre where The Young Australian Band played "The Blondin March", a piece composed specially by their conductor Mr J. Devlin. He was presented with a large gold star, engraved with a scene of his latest triumph, the date of his public performance. Measuring 3 inches (76 mm) across, it was centred with a 1½ carat diamond and suspended by a blue ribbon to a clasp featuring the Australian coat of arms in silver. An illuminated address and a bag of sovereigns, collected from his admirers, were also given.[10] L'Estrange thereafter took his show on the road, going first to Brisbane in May 1877,[6] and reportedly afterwards to Singapore, England and America.[1]

Ballooning

In April 1878, L'Estrange reappeared on the Australian scene with a new performance – gas ballooning. The first balloon ascent in Australia had been made in Melbourne in 1853, with Sydney following five years later in December 1858. The idea that people could be lifted from the ground to fly and return safely fired the imagination of the public, and the novelty of balloon ascents continued to draw large crowds through the 1860s and 1870s. No doubt the very real chance of disaster and injury added to the crowd's keen interest, as mishaps were not uncommon.

L'Estrange came to Sydney with his balloon in November 1878, accompanied by reports of successful flights already made in India and The Sydney Morning Herald offered a confident appraisal of L'Estrange's new venture:[11]

L'Estrange's] balloon has been fitted with the newest applications, amongst others a parachute, which in the event of anything going wrong, would prevent the too rapid descent of the aerial voyager. Another novelty is the fixing of bags of sand round the mesh which covers the balloon, the principle of which is that by emptying these, and so lessening the weight, the balloon will ascend. The process is chiefly intended to be an easy method of avoiding buildings... He is perfectly confident that he will prove successful in travelling amongst the regions of the clouds, and, if so it will prove an agreeable variety after the many failures we have had.

— The Sydney Morning Herald 1 November 1878[11]

In a letter to the Sydney City Council, L'Estrange sought permission for the use of the Exhibition grounds in Prince Alfred Park, behind Central railway station for his first attempt.[12] L'Estrange struggled to fill the balloon through the afternoon of 17 November 1878, with gas supplied by the Australian Gas Light Company. By 5pm, the crowd was getting restless and L'Estrange decided to attempt liftoff, despite the balloon not being fully inflated. To lighten the load he removed the car in which he was to sit and instead sat in a loop of rope. The balloon managed only to drag him across the park before clearing the fenceline and landing on a railway truck in the yards of Central railway station next to the park. L'Estrange blamed the failure on having been supplied with "dense" gas and a filling pipe that was too narrow and leaky.[13]

L'Estrange wrote to the Council again, this time asking for permission to use Belmore Park for a second attempt.[14] Much like his first attempt, the second ended in failure. Once again the balloon took much of the day to fill, with the lift going ahead at 5 pm on the afternoon of 7 December 1878. The first attempt dragged him approximately 100 yards (91 m) through the crowd. Returning to the start point, L'Estrange tried again, shooting up into the air approximately 50 feet (15 m) and sailing away towards the south, before descending again and being dragged across the park. The crowd feared the balloon would crash but once more it lifted, up and over the roof of Carters' Barracks. L'Estrange, realising that the balloon was not going to lift higher, threw out the anchor, which caught in the spouting of a building and threw the balloon into the drying yard of the Benevolent Asylum, where it caught in the washing lines and wires and was practically destroyed.[15] Still, L'Estrange's place in Sydney hearts had been established and a well-attended benefit was held at the Theatre Royal on 19 December 1878.

L'Estrange survived an even more disastrous attempt in Melbourne less than six months later at the grounds of the Agricultural Society in a balloon named Aurora. Having been supplied with a much higher quality gas from the Metropolitan Gas Company he miscalculated the speed at which the balloon would ascend. Having floated much higher than originally anticipated the balloon greatly expanded and a weak seam in the calico fabric suddenly burst. L'Estrange had the presence of mind to deploy the silk parachute which slowed the rate of descent. His landing was softened by a tree and although severely shaken, L'Estrange was uninjured. The whole journey took nine minutes.[16] The "catastrophe" was widely reported with the story appearing in local newspapers in Adelaide,[17] Canberra,[18] Sydney[19] and Brisbane[20] within the week. This was the first emergency descent by parachute in Australia,[21] predating the Caterpillar Club by over 50 years.

Despite these setbacks, L'Estrange persisted, returning to Sydney in August 1880 to prepare for another attempt. Success finally came with a flight on 25 September 1880 from Cook Park, Northwards over the Garden Palace and Sydney Harbour to Manly.[22]

Final balloon flight

Buoyed by his achievement, L'Estrange set himself a second flight day in March 1881. With his reputation already well known in Sydney, and a successful flight on record, a crowd of over 10,000 turned up in the Outer Domain.

As a result of high atmospheric pressure and heavy dew weighing down the balloon, inflation took longer than anticipated, and the crowd grew restless. The officer representing the company supplying the gas also refused to provide a new supply. L'Estrange was presented with what was described as a "Hobson's choice",[23] "...either to abandon the attempt and risking being seriously maltreated by the mob, or proceed heavenwards without the car, accepting the attendant [risks] of such an aerial voyage."[24] He chose the latter and the lift commenced at 9.30 pm with L'Estrange sitting in a loop of rope much like his attempt three years previously. At first all seemed well, as the balloon lifted above the heads of the crowd, hovering for a moment before first heading over Hyde Park. He described the rest of his voyage in a letter to a friend:

I then got into a westerly current that took me out to sea, on which I determined to come down to mother earth without delay, but picture to yourself my horror when I found the escape valve would not act. I tried with all the strength of the one hand I had to spare to move it, for with the other I had to hold myself in the loop of rope, but all to no purpose, it would not budge an inch. In sheer desperation I took the valve rope in both hands, and it opened with a bang ; but in the effort I had lost my seat in the loop, falling about six feet, and there I was dangling in mid air, clutching the valve rope, the gas rushing out of the balloon as though she had burst...

— printed in Illustrated Sydney News, 23 April 1881[25]

Managing to right himself, he became faint from the escaping gas and lashed himself to the ropes to prevent a fall. Realising the attempt was now a danger to himself and the balloon, L'Estrange set out the grappling hooks to catch onto something and bring the balloon down. However the ropes had become tangled and the hooks were too short.[23]

L'Estrange's balloon descended rapidly over the rooftops of Woolloomooloo, slamming into a house near the corner of Palmer Street and Robinson Lane. L'Estrange managed to disentangle himself and fell first onto a chimney then a shed 25 feet (7.6 m) below. He scrambled down from the rooftops to a waiting mob, who whisked him away to Robinson's hotel on the William Street corner and would not let him leave.[25] At the crash site, during an attempt to free the balloon, the escaping gas was ignited when the resident of the house opened a window to see what the commotion was and the gas came into contact with the open flame of the room's chandelier. The resulting fireball destroyed the balloon, burnt a number of bystanders and was bright enough to "...cast a brief but vivid illumination over the entire suburb".[24] A panicked crush developed as groups tried to both flee from and rush towards the brief, but extremely bright, conflagration while those further away at the launch site assumed L'Estrange had been killed.[23] Several people were injured in the crush or burned by the fire with one lady reportedly being blinded.[26]

Although a Masonic benefit was held in his honour to try to recoup some of his financial losses, the fiasco spelt the end of L'Estrange's aeronautical career.

Return to tightrope walking

In a change of direction in March 1882, L'Estrange applied to the Sydney City Council to establish a juvenile pleasure gardens at the Paddington Reservoir. The fun park was to have a variety of rides, a maze, merry-go-round and a donkey racecourse. L'Estrange proposed the park to be free entry with all monies being made via the sale of refreshments on site. While he was given permission, the park does not appear ever to have opened.[27]

Following the disastrous balloon attempt and the failed pleasure grounds, L'Estrange decided to return to what he knew best, tightrope walking. In April 1881 L'Estrange, given top billing as "the hero of Middle Harbour", performed at the Garden Palace on the high-rope as part of the Juvenile Fete, with other acrobats, contortionists and actors.[28] With proof of the continuing popularity of the rope act, he decided to return to his greatest triumph; the spectacular crossing of the harbour in 1877 which had still not been repeated. On 23 December 1882, L'Estrange advised the public that he would cross the harbour once more, this time riding a bicycle across Banbury Bay, close to the site of his original success.[29]

As with his previous crossings, steamers took the crowds from Circular Quay, although this time only four were needed, while another 600–700 people made their own way to the site. The ride was scheduled for 3 pm on 23 December, but delays meant L'Estrange did not appear until 6 pm. Although the length of rope was over 182 metres, it was only just over nine metres above the water. The stay wires were held in boats on either side, with the crews rowing against each other to keep it steady. L'Estrange rode his bicycle towards the centre, where, with the rope swinging to and fro, he stopped briefly to steady himself but instead, realising he was losing his balance, he was forced to leap from the rope and fell into the water below. Although he was unhurt, it was another knock to his reputation. A repeat attempt was announced for the following weekend. Again steamers took a dwindling crowd to Banbury Bay where they found L'Estrange's rope had been mysteriously cut, and he cancelled the performance. The Daily Telegraph reported that many in the crowd, who had paid for tickets on the steamers, felt they had been scammed.[30]

Late career

With his reputation in tatters after the balloon crash and the attempted second harbour crossing, L'Estrange slowly slipped out of the public eye. In December 1883 he was reported as performing again on the highwire at the Parramatta Industrial Juvenile exhibition. While his act attracted favourable publicity, "his efforts were not received with the amount of enthusiasm they certainly deserved".[31]

In April 1885 a benefit was held for L'Estrange, again at the Masonic Lodge, like the one held after his balloon misadventure. It was advertised that the benefit, under the patronage of the Mayor and Aldermen of Sydney, and with Bill Beach, world champion sculler in attendance, was prompted because L'Estrange had "lately met with a severe accident".[32] The nature of the accident is unknown, but it is speculated to have been a fall from his tightrope, explaining the end of his performances.[1]

His apparent decline in popularity may have been as much a reflection of the public's changing taste for entertainment as it was a comment on his act. By the time L'Estrange returned to Sydney to attempt his second harbour crossing in 1882, the city was awash with Blondin imitators performing increasingly dangerous, and probably illegal, feats.[33] At least five were performing in Sydney from 1880 under variations of the title from the "Young Blondin" (Alfred Row) to the "Blondin Brothers" (Alexander and Collins), the "Great Australian Blondin" (James Alexander), the "original Australian Blondin" (Collins), the "Great Australian Blondin" (Signor Vertelli), the "Female Australian Blondin" (Azella) and another "Australian Blondin" (Charles Jackson).[1]

In 1886 L'Estrange again applied to the Sydney City Council for permission to establish an amusement ride called "The Rocker" in Belmore Park. The Rocker consisted of a boat which, propelled by horsepower, gave the impression of being at sea. Permission was granted but like his juvenile pleasure grounds, there is no evidence that it was ever erected.[34] After this, L'Estrange slipped from view in Sydney. In 1894 Edwin L'Estrange "who a few years ago acquired some celebrity as the Australian Blondin" appeared in court in Fitzroy, Victoria having been knocked down and run over by a horse and buggy being driven by a commercial traveller. The driver was fined and L'Estrange's injuries are not recorded.[35]

Other 'Australian Blondins'

It appears L'Estrange was the first 'Australian Blondin', but several others used the name,[36] such as Alfred Row as the Young Blondin, and James Alexander as the great Australian Blondin.[37][38][39]

In popular culture

A children's book featuring L'Estrange's exploits entitled The Marvellous Funambulist of Middle Harbour and Other Sydney Firsts was published in 2015.[40]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mark Dunn (2011). "L'Estrange, Henri". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "L'Estrange's Rope-Walk over Middle Harbour". The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 April 1877. p. 5. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "Mercury". The Mercury (Hobart). Hobart. 28 February 1873. p. 2.

- ↑ "Blondin's First Appearance". The Empire. Sydney. 31 August 1874. p. 2. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "CRICKET". The Sydney Morning Herald. 27 January 1877. p. 3. Retrieved 19 December 2011 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 "Intercolonial News". The Queenslander. Brisbane. 28 April 1877. p. 27. Retrieved 19 December 2011 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 "Sydney Harbour Crossed on a Tight Rope". Australian Town and Country Journal. 7 April 1877. p. 20. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ↑ "Social". The Sydney Morning Herald. 4 May 1877. p. 7. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ↑ "Rope Walking Exhibitions". The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser. 21 April 1877. p. 496. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ↑ "The Sydney Morning Herald". The Sydney Morning Herald. 24 April 1877. p. 4. Retrieved 19 December 2011 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 "SMH". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 12, 622. New South Wales, Australia. 1 November 1878. p. 5. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ↑ City of Sydney Archives, 2 November 1878, Letters Received 26/154/0981. Cited in Dictionary of Sydney.

- ↑ "Amusements". The Sydney Morning Herald. 18 November 1878. p. 5. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ City of Sydney Archives, 21 November 1878, Letters Received 26/154/1044. Cited in Dictionary of Sydney.

- ↑ "Amusements". The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 December 1878. p. 5. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "A Balloon Catasprophe". The Argus. Melbourne. 15 April 1879. p. 5. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "A Balloon Catastrophe". South Australian Register. Adelaide. 18 April 1879. p. 5. Retrieved 20 December 2011 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "A Balloon Catastrophe". Queanbeyan Age. NSW. 19 April 1879. p. 3. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Victoria". The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 April 1879. p. 5. Retrieved 20 December 2011 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Melbourne". The Brisbane Courier. 16 April 1879. p. 2. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ Frank Mines. "A Draft History Of Parachuting In Australia Up To The Foundation Of Sport Parachuting In 1958: The First Emergency Descent". Australian Parachuting Foundation. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "L'Estrange's Balloon Ascent". The Sydney Morning Herald. 27 September 1880. p. 6. Retrieved 19 December 2011 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 3 "L'Estrange's Balloon Ascent". The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 March 1881. p. 6. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- 1 2 "L'Estrange's Balloon Ascent". The Queenslander. Brisbane. 26 March 1881. p. 406. Retrieved 19 December 2011 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 "The Balloon Explosion in Sydney". Illustrated Sydney News. 23 April 1881. p. 14. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Distribution of Awards at the Exhibition". Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil. Melbourne. 9 April 1881. p. 113. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ City of Sydney Archives, 22 March 1882, Letters Received 26/183/475. Cited in Dictionary of Sydney.

- ↑ "Advertising". The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 April 1881. p. 2. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Advertising". The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 December 1882. p. 2. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "The "Blondin" Fiasco". The Sydney Daily Telegraph. 1 January 1883. p. 3. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ↑ "Parramatta Industrial Juvenile Exhibition". The Sydney Morning Herald. 31 December 1883. p. 4. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Advertising". The Sydney Morning Herald. 14 April 1885. p. 2. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Dangerous Sports". The Sydney Morning Herald. 19 February 1880. p. 8. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ City of Sydney Archives, 12 January 1886, Letters Received 26/209/0105. Cited in Dictionary of Sydney.

- ↑ "Fitzroy - Thursday". Fitzroy City Press. Vic. 28 September 1894. p. 3. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ DUNN, Mark (2011). "L'Estrange, Henri". The Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ↑ "BLONDIN". The Ballarat Star. Vol. XXVII, no. 311. Victoria, Australia. 3 January 1882. p. 2. Retrieved 7 January 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Letters to the Editor. "The Australian Blondin"". The Mercury. Vol. XLVI, no. 4, 750. Tasmania, Australia. 12 May 1885. p. 3. Retrieved 7 January 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "ALEXANDER still BLONDIN". Geelong Advertiser. No. 21, 525. Victoria, Australia. 29 April 1916. p. 3. Retrieved 7 January 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Bell, Hilary (2015). The Marvellous Funambulist of Middle Harbour and Other Sydney Firsts. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing. ISBN 9781742234403.

written by Mark Dunn, 2011 and licensed under CC by-sa. Imported on 18 December 2011 (Archive of the original).