Greenbacks were emergency paper currency issued by the United States during the American Civil War that were printed in green on the back.[1] They were in two forms: Demand Notes, issued in 1861–1862,[1] and United States Notes, issued in 1862–1865.[2] A form of fiat money, the notes were legal tender for most purposes and carried varying promises of eventual payment in coin but were not backed by existing gold or silver reserves.[3]

History

Background

Before the Civil War, the United States used gold and silver coins as its official currency. Paper currency in the form of banknotes was issued by privately owned banks, the notes being redeemable for specie at the bank's office. Such notes had value only if the bank could be counted on to redeem them; if a bank failed, its notes became worthless. The federal government sometimes issued Treasury Notes to borrow money during periods of economic distress, but proposals for a federal paper currency were politically contentious and recalled the experience of the Continental dollars issued during the American Revolution. These were nominally payable in silver, but rapidly depreciated due to British counterfeiting and the Continental Congress's difficulty in collecting money from the states.

The Buchanan administration had run chronic deficits as the country weathered the Panic of 1857. The southern secession movement worsened the situation, as the government lost substantial tax revenue.[4] It continued to operate during the presidential transition on private bank loans at rates up to 12 percent, with some banks asking as much as 36.[5] Salmon P. Chase, as the Treasury secretary of the incoming Lincoln administration, found the banks more receptive but struggled to keep enough coins in the Treasury to meet expenditures.[6]

Demand Notes

The first measure to finance the war occurred in July 1861, when Congress authorized $50,000,000 (~$1.29 billion in 2022) in Demand Notes. They bore no interest but could be redeemed for specie "on demand." Unlike state and some private banknotes, Demand Notes were printed on both sides. The reverse side was printed in green ink, so Demand Notes were dubbed "greenbacks." Initially, they were discounted relative to gold, but being fully redeemable in gold, they were soon at par. In December 1861, the government had to suspend redemption, and the Demand Notes declined.

The later United States Notes could not be used to pay customs duties or interest on the public debt, which could be paid only by gold and Demand Notes. Importers, therefore, continued to use Demand Notes in place of gold. In March 1862, Demand Notes were made legal tender. As Demand Notes were used to pay duties, they were taken out of circulation.

United States Notes

The number of Demand Notes issued was far insufficient to meet the war expenses of the government but even so was not supportable. The solution came from Colonel "Dick" Taylor, an Illinois businessman who was serving as a volunteer officer. Taylor met with Lincoln in January 1862 and suggested issuing unbacked paper money.[7] On February 25, 1862, Congress passed the first Legal Tender Act, which authorized the issuance of $150 million (~$3.44 billion in 2022) in United States Notes.[8]

Since the reverse of the notes was printed with green ink, they were called "greenbacks" by the public and considered to be equivalent to the Demand Notes, which were already known as such. The United States Notes were issued by the United States to pay for labor and goods.[9]

Earlier, Secretary Chase had the slogan "In God We Trust" engraved on U.S. coins. During a cabinet meeting, there was some discussion of adding it to the U.S. Notes as well. Lincoln, however, humorously remarked, "If you are going to put a legend on the greenbacks, I would suggest that of Peter and Paul, 'Silver and gold I have none, but such as I have I give to thee.'"[nb 1]

California and Oregon defied the Legal Tender Act. Gold was more available on the West Coast, and merchants in those states did not want to accept U.S. Notes at face value. They blacklisted people who tried to use them at face value. California banks would not accept greenbacks for deposit, and the state would not accept them for payment of taxes. Both states ruled that greenbacks were a violation of their state constitutions.[10]

As the government issued hundreds of millions in greenbacks, their value against gold declined. The decline was substantial, but was nothing like the collapse of the continental dollar.

In 1862, the greenback declined against gold until by December, gold had become at a 29% premium. By spring of 1863, the greenback declined further, to 152 against 100 dollars in gold. However, after the Union victory at Gettysburg, the greenback recovered to 131 dollars to 100 in gold. In 1864, it declined again, as Grant was making little progress against Lee, who held strong in Richmond throughout most of the war. The greenback's low point came in July that year, with 258 greenbacks equal to 100 gold. When the war ended in April 1865 the greenback made another recovery to 150.[11] The recovery began when Congress limited the total issue of greenback dollars to $450 million. The greenbacks rose in value until December 1878, when they became on par with gold. Greenbacks then became freely convertible into gold.[12]

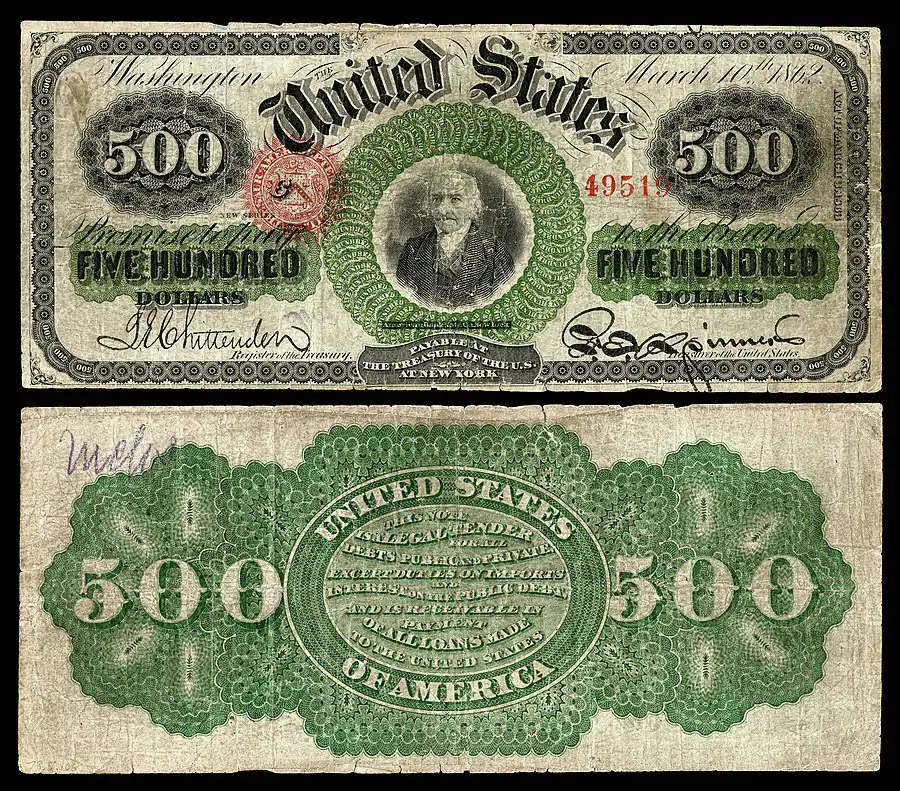

Complete set of 1862–63 greenbacks

| Issue | Date[13] | Denominations |

|---|---|---|

| First | March 10, 1862 | $5, $10, $20 |

| Second | August 1, 1862 | $1 & $2 |

| Third | March 10, 1863 | $50 to $1,000 |

| Obligation | Obligation text[13] |

|---|---|

| First | This note is a legal tender for all debts, public and private, except duties on imports and interest on the public debt, and is exchangeable for the U.S. six percent twenty-year bonds, redeemable at the pleasure of the United States after five years. |

| Second | This note is a legal tender for all debts, public and private, except duties on imports and interest on the public debt, and is receivable in payment of all loans made to the United States. |

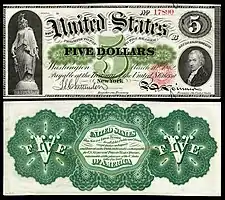

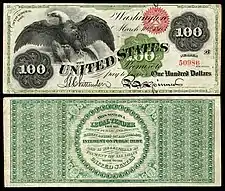

| Value | Year | Obligation | Fr. | Image | Portrait[nb 2] | Population[nb 3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $1 | 1862 | Second[nb 4] | Fr.16c |  |

Salmon P. Chase (Joseph P. Ourdan)[15] | 2,607 (194) |

| $2 | 1862 | Second | Fr.41 |  |

Alexander Hamilton | 1,212 (881) |

| $5 | 1862 | First | Fr.61a |  |

Freedom (Owen G. Hanks, eng; Thomas Crawford, art)[16] Alexander Hamilton | 1,591 (188) |

| $10 | 1863 | First | Fr.95b |  |

Abraham Lincoln (Frederick Girsch);[17] Eagle; Art | 375 (161) |

| $20 | 1863 | First | Fr.126b |  |

Liberty | 375 (161) |

| $50 | 1862 | Third | Fr.148a |  |

Alexander Hamilton (Joseph P. Ourdan)[18] | 45 (1) |

| $100 | 1863 | Third | Fr.167 |  |

Vignette spread eagle (Joseph P. Ourdan)[19] | 51 (2) |

| $500 | 1862 | Third | Fr.183c |  |

Albert Gallatin | 6 (4) |

| $1,000 | 1863 | Third | Fr.186e |  |

Robert Morris (Charles Schlecht) | 4 (1) |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Acts 3:6

- ↑ Names in parentheses are either the engravers or artists responsible for the concept and/or initial design.

- ↑ The first number represents the total population for the design type, the second number (in parentheses) is the total number of notes known for the variety illustrated in the table.

- ↑ The $1 and $2 denominations were only issued with the Second obligation on the reverse. All other denominations were issued with both payment obligations.[14]

References

- 1 2 Spencer C. Tucker (2013). American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection [6 volumes]: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. p. 809. ISBN 9781851096824.

- ↑ Richard H. Timberlake (1993). Monetary Policy in the United States: An Intellectual and Institutional History. University of Chicago Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780226803845.

- ↑ Brands 2011, p. 1.

- ↑ Mitchell 1903, p. 5.

- ↑ Mitchell 1903, p. 7.

- ↑ Mitchell 1903, p. 23.

- ↑ Lincoln, Abraham; et al. (Hobson, J.T.) (1912). The Lincoln Year Book: Containing Immortal Words of Abraham Lincoln Spoken and Written on Various Occasions, Preceded by Appropriate Scripture Texts and Followed by Choice Poetic Selections for Each Day in the Year, with Special Reference to Anniversary Dates (First ed.). Dayton, Ohio: Press of United Brethren publishing house. p. 348.

- ↑ Brands 2011, p. 12.

- ↑ O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003). Economics: Principles in Action. Needham, MA: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 552. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.

- ↑ Paul, Ron; Lewis, Lehrman (1982). The Case for Gold: A Minority Report of the U.S. Gold Commission (PDF). Auburn, AL: Cato Institute. p. 79. ISBN 0-932790-31-3.

- ↑ Brands 2011, p. 13.

- ↑ "BEP HISTORY FACT SHEET - UNITED STATES NOTES". The Bureau of Engraving & Printing, Department of the Treasury. Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 14th and C Streets, SW, Washington, DC 20228, Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Western Currency Facility, 9000 Blue Mound Road, Fort Worth, TX 76131. April 2013. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: location (link) - 1 2 Friedberg & Friedberg 2013, p. 37.

- ↑ Friedberg & Friedberg 2013, pp. 37–56.

- ↑ Hessler 2004, p. 24.

- ↑ Hessler 2004, p. 20.

- ↑ Hessler 2004, p. 22.

- ↑ Hessler 2004, p. 27.

- ↑ Hessler 2004, p. 28.

Sources

- Brands, H. W. (2011). Greenback Planet: How the Dollar Conquered the World and Threatened Civilization as We Know It. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292739338.

- Friedberg, Arthur L.; Friedberg, Ira S. (2013). Paper Money of the United States (20th ed.). Coin & Currency Institute. ISBN 978-0-87184-020-2. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Hessler, Gene (2004). U.S. Essay, Proof and Specimen Notes (2nd ed.). BNR Press. ISBN 0-931960-62-2.

- Mitchell, Wesley Clair (1903). A history of the greenbacks: with special reference to the economic consequences of their issue: 1862–65. University of Chicago Press.

- Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson (1904). Abraham Lincoln. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs. Vol.I Vol.II

- Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson (1907). Jay Cooke: Financier of the Civil War. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs. Vol.I Vol.II

Further reading

- Bye, John O. (1963). Lincoln's greenback currency. University of Michigan.

- Noll, Franklin (March 2012). "The United States Monopolization of Bank Note Production: Politics, Government, and the Greenback, 1862–1878". American Nineteenth Century History. 13 (13): 15–43. doi:10.1080/14664658.2012.681942. S2CID 144566502.