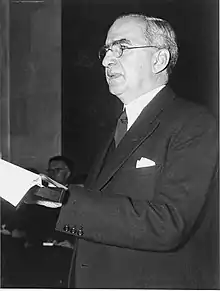

George S. Messersmith | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Ambassador to Argentina | |

| In office April 12, 1946 – June 12, 1947 | |

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Spruille Braden |

| Succeeded by | James Cabell Bruce |

| United States Ambassador to Mexico | |

| In office February 24, 1942 – May 15, 1946 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Josephus Daniels |

| Succeeded by | Walter C. Thurston |

| United States Ambassador to Cuba | |

| In office March 8, 1940 – February 8, 1942 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | J. Butler Wright |

| Succeeded by | Spruille Braden |

| United States Assistant Secretary of State | |

| In office July 9, 1937 – February 15, 1940[1] | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Sumner Welles |

| Succeeded by | Hugh R. Wilson |

| United States Ambassador to Austria | |

| In office April 7, 1934 – July 11, 1937 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | George Howard Earle III |

| Succeeded by | Grenville T. Emmet |

| Personal details | |

| Born | George Strausser Messersmith October 3, 1883 Fleetwood, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | January 29, 1960 (aged 76) |

| Profession | Lawyer, Diplomat |

George Strausser Messersmith (October 3, 1883 – January 29, 1960) was a United States ambassador to Austria, Cuba, Mexico, and Argentina. Messersmith also served as head of the consulate in Germany from 1930 to 1934, during the rise of the Nazi Party.[2]

He was best known in his day for his controversial decision to issue a visa to Albert Einstein to travel to the United States.[3] He is also known today for his diplomatic handling of Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson, later Duke and Duchess of Windsor, in the era before World War II.[4]

Education and early career

Messersmith, a graduate of Keystone State Normal School,[2] was a teacher and then school administrator from 1900 to 1914. Then, he entered the foreign service[5] and left his position as vice president of the Delaware State Board of Education to become US consul in Fort Erie, Ontario.[6]

After serving as a US consul at Curacao (1916–1919) and Antwerp (1919–1925), he became US Consul General for Belgium and Luxembourg in 1925.[7] He served as US Consul General in Buenos Aires, Argentina, from 1928 to 1930.[5]

Consul for Berlin

In 1930, Messersmith left his position in Argentina to accept the same position in Berlin.[8] There, he became responsible for administering the annual German quota.[9]

While he did not personally interview Albert Einstein, Messersmith cleared the way for the scientist to leave Germany.[9][10][11] He called Einstein himself to tell him that his visa would be ready.[11] He was viciously criticized by conservative groups and media for his action to issue a visa to Einstein.[3][10][12] Messersmith received significant notoriety in late 1932 due to the incident.[3]

Messersmith told the American consuls in Europe that refugees or immigrants requesting a visa to enter the US had to have sufficient funds and property to support themselves.[9]

As America's consul general in Berlin in 1933, Messersmith wrote a dispatch to the State Department that dramatically contravened the popular view that Hitler had no consensus among the German people and would not remain in power:

I wish it were really possible to make our people at home understand how definitely this martial spirit is being developed in Germany. If this government remains in power for another year, and it carries on in the measure in this direction, it will go far toward making Germany a danger to world peace for years to come. With few exceptions, the men who are running the government are of a mentality that you and I cannot understand. Some of them are psychopathic cases and would ordinarily be receiving treatment somewhere."[13]

Minister to Austria

His service in Germany ended in February 1934, when President Franklin Roosevelt nominated him to be US Ambassador to Uruguay,[14] only to renominate him the next month as Minister to Austria before his service in Uruguay could begin.[15]

On January 17, 1935, Edward Albert (later Edward VIII), the Prince of Wales, was visiting Vienna on vacation with his new mistress, Wallis Simpson. While Simpson went shopping, Edward met with President Wilhelm Miklas and Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg of Austria. Messersmith had spies at the meeting who reported to the State Department through him on the meeting's goal: solidifying the Balkan Pact.[16]

When Edward abdicated in December 1936, he visited Messersmith, who spied on him, in Vienna and made "what amounted to a detailed watching brief on the duke."[17] They became friends, even attending Christmas day services together later that month.[17]

Messersmith continued to socialize with Edward, attending a concert by soprano Joan Hammond on February 3, 1937.[18] That month, Edward confided in him that the Earl of Harewood, his brother-in-law, had treated him "shabbily."[18] After the Duke and the Duchess of Windsor were married in June 1937, they honeymooned in Austria, and Simpson confided to Messersmith about her bitterness towards the American media.[19]

In return, Messersmith accidentally leaked through them that the Americans knew that Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy had secret connections as early as that month.[19] When Messersmith returned to Washington, D.C., in August 1937, he informed the British authorities that the Windsors had Nazi connections, which "would seriously affect the Windsors' entire future."[19]

Later career

From 1937 to 1940, between his appointments as Minister to Austria and Ambassador to Cuba, he served as a US Assistant Secretary of State. As chief of the Foreign Service Promotion Board, Messersmith had to go over all appointments with President Roosevelt and in the process learned that Roosevelt had excellent intelligence on several foreign service officers with problems, including alcohol or affairs.[20]

While Messersmith served as United States Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Cuba, he wrote a report on March 4, 1941, about the Windsors' friend, James D. Mooney, and was critical of the General Motors executive's opinions against England.[21] He considered that Mooney was "dangerous... for the Duke and Duchess of Windsor to be associated with."[21] However, the Windsors visited Mooney in Detroit in November 1941, the month before the attack on Pearl Harbor.[21]

Later, he was appointed United States Ambassador to Mexico, where he passed on information about the Windsors' Nazi connections to Assistant Secretary of State Adolph A. Berle.[22] Messersmith "no longer adhered to his moderate view of the duke and duchess.".[22] During his tenure, in 1942, he helped establish the Benjamin Franklin Library in Mexico City and The American Society of Mexico, an umbrella group to help coordinate the whole American community in Mexico.

Following the forced resignation of Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles in 1943, Messersmith, then Ambassador to Mexico, was rumored to be on a short list of candidates to succeed him,[23] but Roosevelt instead selected future Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, Jr.

Legacy

Messersmith's collection of papers has been digitized[24] and made available to researchers by the University of Delaware. The digitization project was made possible through a grant[25] from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC).

References

- ↑ Plischke, Elmer (January 1, 1999). U.S. Department of State: A Reference History. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-313-29126-5. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- 1 2 Stiller, Jesse H. (1987). George S. Messersmith, Diplomat of Democracy. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1721-6.

- 1 2 3 Schaap, Jeremy (2007). Triumph: The Untold Story of Jesse Owens and Hitler's Olympics. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 71, 242. ISBN 978-0-618-68822-7. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ↑ Higham, Charles (1988). The Dutchess of Windsor: The Secret Life. McGraw Hill.

- 1 2 "Foreign Affairs: Career Man's Mission," Time, 1946-12-02.

- ↑ "National Affairs: Messersmith to Mexico," Time, 1941-12-08.

- ↑ Stephen R. Wenn, "A Tale of Two Diplomats: George S. Messersmith and Charles H. Sherrill on Proposed American Participation in the 1936 Olympics Archived 2012-02-04 at the Wayback Machine," 16 Journal of Sport History 27, 30 (Spring 1989).

- ↑ Peter Edson, " . . . Liberator or Dictator?" (commentary), Sandusky Register Star News, 1947-02-06 at p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Breitman, Richard; Kraut, Alan M. (1987). American Refugee Policy and European Jewry, 1933-1945. Indiana University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-253-30415-5. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- 1 2 Jerome, Fred (June 17, 2003). The Einstein File: J. Edgar Hoover's Secret War Against the World's Most Famous Scientist. St. Martin's Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4299-7588-9. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- 1 2 Mauro, James (June 22, 2010). Twilight at the World of Tomorrow: Genius, Madness, Murder, and the 1939 World's Fair on the Brink of War. Random House Publishing Group. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-345-52178-1. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ↑ McDonald, James Grover (2007). Advocate for the Doomed: The diaries and papers of James G. McDonald, 1932-1935. Indiana University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-253-34862-3. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ↑ "George S. Messersmith Papers". Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ↑ "The Presidency: $20,000,000 Fine," Time, 1934-02-19.

- ↑ "The Presidency: Great Day," Time, 1934-04-02.

- ↑ Higham, Charles (1988). The Dutchess of Windsor: The Secret Life. McGraw Hill. pp. 112–113.

- 1 2 Higham, Charles (1988). The Duchess of Windsor: The Secret Life. McGraw Hill. pp. 192, 194. ISBN 9780070288010.

- 1 2 Higham, Charles (1988). The Dutchess of Windsor: The Secret Life. McGraw Hill. pp. 197–198.

- 1 2 3 Higham, Charles (1988). The Duchess of Windsor: The Secret Life. McGraw Hill. pp. 221–222, 225. ISBN 9780070288010.

- ↑ Morgan, Ted (1985). FDR: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 547–548. ISBN 9780671454951.

- 1 2 3 Higham, Charles (1988). The Duchess of Windsor: The Secret Life. McGraw Hill. pp. 311–312, 328.

- 1 2 Higham, Charles (1988). The Dutchess of Windsor: The Secret Life. McGraw Hill. pp. 323–324.

- ↑ "One More Scalp," Time, 1934-09-06.

- ↑ "George S. Messersmith Papers". Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ↑ "NHPRC Delaware Grants". Retrieved 29 June 2011.

Further reading

- Jones, Kenneth Paul, ed. U.S. Diplomats in Europe, 1919–41 (ABC-CLIO. 1981) online on Messersmith's role in Europe, pp 113–128.