A droll is a short comical sketch of a type that originated during the Puritan Interregnum in England. With the closure of the theatres, actors were left without any way of plying their art. Borrowing scenes from well-known plays of the Elizabethan theatre, they added dancing and other entertainments and performed these, sometimes illegally, to make money. Along with the popularity of the source play, material for drolls was generally chosen for physical humor or for wit.

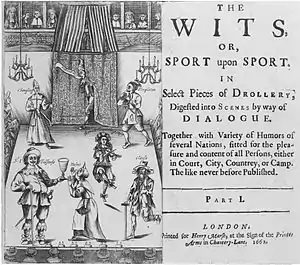

Francis Kirkman's The Wits, or Sport Upon Sport, 1662, is a collection of twenty-seven drolls. Three are adapted from Shakespeare: Bottom the Weaver from A Midsummer Night's Dream, the gravedigger's scene from Hamlet, and a collection of scenes involving Falstaff called The Bouncing Knight. A typical droll presented a subplot from John Marston's The Dutch Courtesan; the piece runs together all the scenes in which a greedy vintner is gulled and robbed by a deranged gallant.

Just under half of the drolls in Kirkman's book are adapted from the work of Beaumont and Fletcher. Among the drolls taken from those authors are Forc'd Valour (the title plot from The Humorous Lieutenant), The Stallion (the scenes in the male brothel from The Custom of the Country), and the taunting of Pharamond from Philaster. The prominence of Beaumont and Fletcher in this collection prefigures their dominance on the early Restoration stage. The extract from their Beggar's Bush, known as The Lame Commonwealth, features additional dialogue, strongly suggesting it was taken from a performance text. The character of Clause, the King of the Beggars in that extract, appears as a character in later works, such as the memoirs of Bampfylde Moore Carew, the self-proclaimed King of the Beggars.

Actor Robert Cox was perhaps the best-known of the droll performers.

References

- Kirkman, Francis. The Wits, or Sport Upon Sport. ed. John James Elson (Cornell University Press, 1932)

- Baskervill, C. R. "Mummers' Wooing Plays in England." Modern Philology, Vol. 21 No. 3 (February 1924),pp. 225–272; see pp. 268–272, folkplay.info