| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

Canine influenza (dog flu) is influenza occurring in canine animals. Canine influenza is caused by varieties of influenzavirus A, such as equine influenza virus H3N8, which was discovered to cause disease in canines in 2004.[1] Because of the lack of previous exposure to this virus, dogs have no natural immunity to it. Therefore, the disease is rapidly transmitted between individual dogs. Canine influenza may be endemic in some regional dog populations of the United States. It is a disease with a high morbidity (incidence of symptoms) but a low incidence of death.[2]

A newer form was identified in Asia during the 2000s and has since caused outbreaks in the US as well. It is a mutation of H3N2 that adapted from its avian influenza origins. Vaccines have been developed for both strains.

The two strains of Type A influenza virus found in canines are A(H3N2) and A(H3N8). Over time, there has been a discovery of sources of transmissions, identification of specific symptoms and the creation of vaccines.[3]

History

The highly contagious equine influenza A virus subtype H3N8 was found to have been the cause of Greyhound race dog fatalities from a respiratory illness at a Florida racetrack in January 2004. The exposure and transfer apparently occurred at horse-racing tracks, where dog racing had also occurred. This was the first evidence of an influenza A virus causing disease in dogs. However, serum collected from racing Greyhounds between 1984 and 2004 and tested for canine influenza virus (CIV) in 2007 had positive tests going as far back as 1999. CIV possibly caused some of the respiratory disease outbreaks at tracks between 1999 and 2003.[4]

H3N8 was also responsible for a major dog-flu outbreak in New York state in all breeds of dogs. From January to May 2005, outbreaks occurred at 20 racetracks in 10 states (Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Kansas, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Texas, and West Virginia).[5] As of August 2006, dog flu has been confirmed in 22 U.S. states, including pet dogs in Wyoming, California, Connecticut, Delaware, and Hawaii.[6] Three areas in the United States may now be considered endemic for CIV due to continuous waves of cases: New York, southern Florida, and northern Colorado/southern Wyoming.[7] No evidence shows the virus can be transferred to people, cats, or other species.[8]

H5N1 (avian influenza) was also shown to cause death in one dog in Thailand, following ingestion of an infected duck.[9]

The H3N2 virus made its first appearance in Canada at the start of 2018, following the importation of two unknowingly infected canines from South Korea. In 2006-2007 canine H3N2 first had reports in South Korea and was thought to be transferred to dogs from avian origins (avian influenza H3N2).[10] It was not until 2015 that the canine H3N2 strain was discovered in the United States after there was an outbreak of dogs having respiratory infections in Chicago.[11] As canine H3N2 influenza began to spread through the United States, in 2016 cats in an Indiana began to show symptoms of the disease as well, it is believed they were infected by coming in to contact with sick dogs.[11]

Following this incidence, reports of the virus possibly spreading, with two other canines reporting alarming symptoms, were made public. By March 5th, 25 cases of infection were reportedly spread, although the number is thought to be closer to approximately 100.[12]

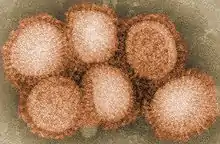

Influenza A viruses are enveloped, negative sense, single-stranded RNA viruses.[13] Genome analysis has shown that H3N8 was transferred from horses to dogs and then adapted to dogs through point mutations in the genes.[14] The incubation period is two to five days, and viral shedding may occur for seven to ten days following the onset of symptoms.[15] It does not induce a persistent carrier state.

In late 2022, together with Bordetella bronchiseptica and other respiratory pathogens, the H3N2 canine flu virus experienced a surge in canine infections. This was partially due to increased human travel and reopened offices following the relaxation of COVID-19 pandemic public health measures, leading to large numbers of dogs being placed together in kennels and doggy day care centers. Changing pet ownership behaviors also led to overcrowded animal shelters, which had been emptied at the height of the pandemic.[16]

Transmissions

The infection of canine influenza can be transmitted from animal to animal and almost all dogs that come in contact with the virus will contract it. This makes canine influenza most common among dogs but can also be transmitted to cats in a shelter or a household.[17] Canine influenza is an airborne disease, when a dog coughs or sneezes they secrete respiratory droplets that are then inhaled by other animals causing infection.[18] Kennels, dog parks, grooming parlors, and things alike are high risk areas for infections.[18]

Symptoms

About 80% of infected dogs with H3N8 show symptoms, usually mild (the other 20% have subclinical infections), and the fatality rate for Greyhounds in early outbreaks was 5 to 8%,[19] although the overall fatality rate in the general pet and shelter population is probably less than 1%.[20] Most animals infected with canine influenza will show symptoms such as coughing, runny nose, fever, lethargy, eye discharge, and a reduced appetite lasting anywhere from 2-3 weeks.[21]

Symptoms of the mild form include a cough that lasts for 10 to 30 days and possibly a greenish nasal discharge. Dogs with the more severe form may have a high fever and pneumonia.[22] Pneumonia in these dogs is not caused by the influenza virus, but by secondary bacterial infections. The fatality rate of dogs that develop pneumonia secondary to canine influenza can reach 50% if not given proper treatment.[23] Necropsies in dogs that die from the disease have revealed severe hemorrhagic pneumonia and evidence of vasculitis.[24]

Diagnosis

The presence of an upper respiratory tract infection in a dog that has been vaccinated for the other major causes of kennel cough increases suspicion of infection with canine influenza, especially in areas where the disease has been documented. A serum sample from a dog suspected of having canine influenza can be submitted to a laboratory that performs PCR tests for this virus.[20]

Vaccine

In June 2009, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) approved the first canine influenza vaccine.[25][26][27][28] This veterinarian provided vaccine help fight the infection and are preventative measures for dogs who are constantly facing exposure of the H3N8 and H3N2 strain.[29]This vaccine must be given twice initially with a two-week break, then annually thereafter.[30]

H3N2 version

A second form of canine influenza was first identified during 2006 in South Korea and southern China. The virus is an H3N2 variant that adapted from its avian influenza origins.[31] An outbreak in the US was first reported in the Chicago area during 2015.[32] Outbreaks were reported in several US states during the spring and summer of 2015[32] and had been reported in 25 states by late 2015.[33]

As of April 2015, the question of whether vaccination against the earlier strain offered protection had not been resolved.[34] The US Department of Agriculture granted conditional approval for a canine H3N2-protective vaccine in December 2015.[33][30][35][36]

In March 2016, researchers reported that this strain had infected cats and suggested that it may be transmitted between them.[37]

Human risk

The H3N2 virus as a stand-alone virus is deemed harmless to humans. According to the Windsor-Essex County Health Unit, it is only when the H3N2 virus strain combines with a human strain of flu, "those strains could combine to create a new virus." The possibility of this is unlikely; however, if an infected dog contracts a human flu, there stands a slight chance.[38]

See also

References

- ↑ "Canine influenza". American Veterinary Medical Association. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ↑ "Media Briefing on Canine Influenza". CDC. September 26, 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-04-10. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ↑ "Key Facts about Canine Influenza (Dog Flu) | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-08-29. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ↑ Rosenthal M (July 2007). "CIV may have started circulating earlier than originally thought". Veterinary Forum. Veterinary Learning Systems. 24 (7): 12.

- ↑ Article 31284, Medical News Today referencing September 26 issue of Science Express (Vol. 309, No. 5743).

- ↑ Tremayne J (August 2006). "Canine flu confirmed in 22 states". DVM: 1, 66–67.

- ↑ Yin S (September 2007). "Managing canine influenza virus". Veterinary Forum. Veterinary Learning Systems. 24 (9): 40–41.

- ↑ Crawford C, Dubovi EJ, Donis RO, Castleman WL, Gibbs EPJ, Hill RC, Katz JM, Ferro P, Anderson TC (2006). "Canine Influenza Virus Infection". Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ↑ Songserm T, Amonsin A, Jam-on R, Sae-Heng N, Pariyothorn N, Payungporn S, Theamboonlers A, Chutinimitkul S, Thanawongnuwech R, Poovorawan Y (2006). "Fatal avian influenza A H5N1 in a dog". Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (11): 1744–7. doi:10.3201/eid1211.060542. PMC 3372347. PMID 17283627.

- ↑ Voorhees IE, Glaser AL, Toohey-Kurth KL, Newbury S, Dalziel BD, Dubovi E, Poulsen K, Leutenegger C, Willgert KJ, Brisbane-Cohen L, Richardson-Lopez J, Holmes EC, Parrish CR (2017). "Spread of Canine Influenza A(H3N2) Virus, United States - Volume 23, Number 12—December 2017 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23 (12): 1950–1957. doi:10.3201/eid2312.170246. PMC 5708240. PMID 28858604.

- 1 2 "Canine influenza". American Veterinary Medical Association. Retrieved 2023-09-29.

- ↑ Ward A (2018-03-05). "Canine influenza reported in several dogs in Orillia". Barrie. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- ↑ ICTVdB Management (2006). 00.046.0.01. Influenzavirus A. In: ICTVdB - The Universal Virus Database, version 4. Büchen-Osmond, C. (Ed), Columbia University, New York, USA

- ↑ Buonavoglia C, Martella V (2007). "Canine respiratory viruses". Vet. Res. 38 (2): 355–73. doi:10.1051/vetres:2006058. PMID 17296161.

- ↑ "Canine Influenza Virus (Canine Flu)". UF College of Veterinary Medicine Public Relations Office. 2005-08-12. Archived from the original on 2006-07-17. Retrieved 2006-08-17.

- ↑ Anthes E (2 December 2022). "Dog Flu Is Back, Too". New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ↑ "Key Facts about Canine Influenza (Dog Flu) | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-08-29. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- 1 2 Burke A (November 3, 2022). "What You Should Know About Dog Flu: Symptoms, Treatment, and Prevention". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 2023-09-29.

- ↑ Carter, G.R., Flores, E.F., Wise, D.J. (2006). "Orthomyxoviridae". A Concise Review of Veterinary Virology. Retrieved 2006-08-17.

- 1 2 de Morais HA (November 2006). "Canine influenza: Risks, management, and prevention". Veterinary Medicine. Advanstar Communications. 101 (11): 714.

- ↑ "Key Facts about Canine Influenza (Dog Flu) | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-08-29. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ↑ "Control of Canine Influenza in Dogs — Questions, Answers, and Interim Guidelines". AVMA. 2005-12-01. Archived from the original on 2006-08-13. Retrieved 2006-08-17.

- ↑ Rosenthal M (February 2007). "Include new virus in the diagnosis of dogs with kennel cough". Veterinary Forum. Veterinary Learning Systems. 24 (2): 12–14.

- ↑ Yoon K, Cooper V, Schwartz K, Harmon K, Kim W, Janke B, Strohbehn J, Butts D, Troutman J (2005). "Influenza virus infection in racing greyhounds". Emerging Infect. Dis. 11 (12): 1974–6. doi:10.3201/eid1112.050810. PMC 3367648. PMID 16485496.

- ↑ "Aphis Issues Conditional License For Canine Influenza Virus Vaccine" (PDF) (Press release). Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS). 23 June 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ↑ "New Vaccine from Intervet/Schering-Plough Animal Health". Schering-Plough. 23 June 2009. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ↑ "Canine Influenza Virus (CIV) Backgrounder" (PDF). Schering-Plough. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ↑ McNeil Jr DG (June 29, 2009). "New Flu Vaccine Approved -- for Dogs". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ↑ "Canine influenza". American Veterinary Medical Association. Retrieved 2023-09-29.

- 1 2 "Dog Flu Vaccination Products". Canine Influenza Vaccines. DogInfluenza.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "FAQ about the H3N2 strain of canine influenza" (PDF). Cornell University. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- 1 2 "Canine Influenza Virus Monitoring Effort" (PDF). Cornell University. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- 1 2 Jan Hoffman (2015-12-15). "Dog Owners Wondering if Fido Needs a Flu Shot". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- ↑ "Key Facts about Canine Influenza (Dog Flu)". Centers for Disease Control. April 22, 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ "Merck Animal Health Pioneers H3N2 Canine Influenza Vaccine". Merck Animal Health. 20 November 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Canine Influenza Vaccine, H3N2, Killed Virus". Zoetis. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Canine Influenza". American Veterinary Medical Association. Archived from the original on 2018-12-14. Retrieved 2016-06-11.

- ↑ "First 2 cases of canine influenza confirmed in Canada". CBC News. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

Further reading

- A New Deadly, Contagious Dog Flu Virus Is Detected in 7 States The New York Times

- States that have identified dogs with CIV

- Canine Influenza from The Pet Health Library

- Canine Influenza from Veterinary Partner

- Canine Influenza Fact Sheet Center for Food Security and Public Health (CFSPH), Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine

- AVMA: canine influenza