Deutsches Uhrenmuseum | |

Main entrance | |

| Location | Furtwangen im Schwarzwald, Germany |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 48°03′03″N 8°12′28″E / 48.05083°N 8.20778°E |

| Type | Local museum, Clock museum |

| Collection size | more than 8,000 items (according to own statement)[1] |

| Website | www |

The German Clock Museum[2] (German: Deutsches Uhrenmuseum) is situated near the centre of the Black Forest town of Furtwangen im Schwarzwald (Germany), a historical centre of clockmaking. It features permanent and temporary exhibits on the history of timekeeping.[3] The museum is part of the local technical college (Hochschule Furtwangen).[4]

About the museum

The German Clock Museum is devoted to the history of timekeeping devices. A major focus is on clockmaking in the Black Forest, both as a cottage industry and on an industrial scale. The museum has an extensive collection of clocks and other artefacts relating to horology, not just those from the Black Forest, but also clocks and watches from around the world and spanning from prehistoric times to the present. The collection includes early cuckoo clocks from the 18th century as well as the prototypes of the modern Black Forest souvenir. The work of Robert Gerwig formed a primary basis of the museum.

Chronology

1852: Robert Gerwig, Director of the Grand Ducal Baden Clockmaking School in Furtwangen, began to collect old clocks as witnesses of traditional handicrafts.

1858: The collection is exhibited for the first time at the Black Forest Industry Exhibition in Villingen.

1874: Historical clocks together with contemporary products of the region are put on display in the newly built trade hall.

1925: The first printed collection catalogue of the Adolf Kistner Historical Clock Collection already lists over 1,000 clocks.

1959: A new building is opened on the site of the old wooden building that had fallen into decay.

1975: The state of Baden-Württemberg purchases the important clock collection from the Kienzle clock factories and transfers it to the museum. Due to the expansion of its collection to include pocket watches and Renaissance clocks, the "Historic Clock Collection" is renamed in 1978 to the "German Clock Museum".

1992: The current museum building is opened. Today, the German Clock Museum is part of Furtwangen University.[5]

Exhibits

Since 2010, the museum has put on a permanent exhibition, covering an area of 1,400 square metres, of the development of clocks and the concept of timekeeping in Western countries.[6] In addition to improvements in the accuracy of timepieces, it also demonstrates the various requirements that clocks and watches met in order to satisfy the needs of the time. Thus, in addition to prize exhibits, the museum also displays objects that, despite their low value, were historically very important. This distinguishes the German Clock Museum from clock collections that display objects that were rather rare and expensive compared with those in typical everyday use.

The circular tour is divided into the sections covering the following themes:

- History of Clocks and Time up to Industrialisation;

- Black Forest Clocks;

- Pocket Watches and Wristwatches;

- Modern Times and Mechanical Musical Instruments.

History of Clocks and Time up to Industrialisation

Until well into the 20th century, clocks were based on the (apparent) course of the sun and the stars in the sky. This connexion is clearly built into the works of the priest-mechanics of the 18th century with their clockwork models of the cosmos.

In addition to the astronomic calendar clock of Benedictine father and later mathematics professor, Thaddäus Rinderle, of 1787 (Inv. 16-0033), the Copernican Planetarium (Inv. 43-0002, 1774) and a globe clock (Globenuhr, Inv. 43-0001, before 1788) by Philipp Matthäus Hahn are part of the collection.

- Selected examples

Astronomic-geographical clock, Thaddäus Rinderle, 1787 (Inv. 16-0033)

Astronomic-geographical clock, Thaddäus Rinderle, 1787 (Inv. 16-0033) Renaissance clock, Hans Koch, around 1580 (K-1288)

Renaissance clock, Hans Koch, around 1580 (K-1288) Ivory sundial, Paulus Reinmann, Nuremberg, 1605 (Inv. 2003-074)

Ivory sundial, Paulus Reinmann, Nuremberg, 1605 (Inv. 2003-074) Grandfather clock face with display of true time, William Scafe, around 1730 (Inv. 2009-054)

Grandfather clock face with display of true time, William Scafe, around 1730 (Inv. 2009-054) Tête de Poupée, Balthazar Martinot, around 1700 (Inv. 2004-119)

Tête de Poupée, Balthazar Martinot, around 1700 (Inv. 2004-119) Astronomic calendar clock, around 1760-1770 (Inv. 16-0014)

Astronomic calendar clock, around 1760-1770 (Inv. 16-0014) Early German precision pendulum clock based on a design by Ignaz Pickel, 1775 (Inv. 2010-051)

Early German precision pendulum clock based on a design by Ignaz Pickel, 1775 (Inv. 2010-051)

Wooden clocks from the Black Forest

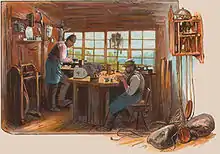

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Black Forest supplied the world with low cost clocks. In many small clockmaking workshops, clocks with wooden movements were made which, thanks to the cheap raw material, the use of special tools and machines and specialised craftsmen, were inexpensive and faced no real competition.

A wooden clock face with a white background and colourfully painted motif decorated the Black Forest clocks during the whole of the 19th century. With a colourless, protective varnish the clock faces were resistant to moisture and dirt. From the second half of the 18th century, the varnished plate clock (Lackschilduhr) dominated the European market. Later, it found its way overseas and to the Far East. The design of the clock plate varied depending on the country being exported to. Black Forest traders, the clock carriers (Uhrenträger), sold the clocks locally.

- Selected examples

Wooden cogwheel clock with figure of Madonna, around 1760 (Inv. 16-0519)

Wooden cogwheel clock with figure of Madonna, around 1760 (Inv. 16-0519) Musical clock with a Baroque face by Matthias Faller (?), around 1770-1780 (Inv. 14-0044)

Musical clock with a Baroque face by Matthias Faller (?), around 1770-1780 (Inv. 14-0044) Cuckoo clock, Johannes Wildi, around 1780 (Inv. 2008-024)

Cuckoo clock, Johannes Wildi, around 1780 (Inv. 2008-024) Watchman's clock (Waechterkontrolluhr), Valentin Kammerer, 1806 (16-0477)

Watchman's clock (Waechterkontrolluhr), Valentin Kammerer, 1806 (16-0477) Painted clock (Lackschilduhr) for the French market, Joseph Hummel, around 1840(Inv. 04-0616)

Painted clock (Lackschilduhr) for the French market, Joseph Hummel, around 1840(Inv. 04-0616) Railway clock for a small station to a design by Friedrich Eisenlohr, Kreuzer, Glatz & Co., ca. 1853/54 (Inv. 2003-081)

Railway clock for a small station to a design by Friedrich Eisenlohr, Kreuzer, Glatz & Co., ca. 1853/54 (Inv. 2003-081) Knödelesser figurine clock, Anton Häckler, around 1870 (Inv. 06-2080)

Knödelesser figurine clock, Anton Häckler, around 1870 (Inv. 06-2080)

Clock industry in the Black Forest

In the second half of the 19th century, clock factories displaced the traditional manufacture of clockmaking in the home. Initially relatively small firms emerged that specialised in the production of short runs of qualitatively high value clocks based on the traditional prototype. Over time the factories that became successful were those, especially in the Württemberg (eastern) half of the Black Forest and neighbouring Baar region, that embraced new types of clock, like alarm clocks, that were suited to industrial processes. In most households there was a clock suited to each room, from the alarm clock to the kitchen clock to the sideboard or wall clock.

- Selected examples

"Bürk Patent" watchman's clock, around 1860 (Inv. 2007-109)

"Bürk Patent" watchman's clock, around 1860 (Inv. 2007-109) Nutmeg alarm clock and W10 movement, Junghans, around 1890 (Inv. 2010-021)

Nutmeg alarm clock and W10 movement, Junghans, around 1890 (Inv. 2010-021) Movement for a Dutch hall clock, L. Furtwängler Söhne, around 1905 (Inv. 16-0663)

Movement for a Dutch hall clock, L. Furtwängler Söhne, around 1905 (Inv. 16-0663) Imperial colonial clock (Reichskolonialuhr), Badische Uhrenfabrik, 1905 (Inv. 1997-029)

Imperial colonial clock (Reichskolonialuhr), Badische Uhrenfabrik, 1905 (Inv. 1997-029) Sideboard clock (Buffetuhr) with German gong, Kienzle Uhren, 1933 (2009-063)

Sideboard clock (Buffetuhr) with German gong, Kienzle Uhren, 1933 (2009-063) Alarm clock with musical mechanism, Fichter, around 1960 (Inv. 2009-098)

Alarm clock with musical mechanism, Fichter, around 1960 (Inv. 2009-098) "Astrochron" quartz crystal clock, Junghans, 1966 (Inv. 1995-603)

"Astrochron" quartz crystal clock, Junghans, 1966 (Inv. 1995-603)

Pocket watches

In the 16th and 17th centuries the sometimes voluminous neck clocks (Halsuhren) were more of an expensive piece of jewellery than an accurate timepiece. Not until the time around 1800 were the first pocket watches available for the landed gentry and for science, but at best they displayed minutes. As a result of industrial manufacturing in the second half of the 19th century, however, the pocket watch became an everyday item.

- Selected examples

Neck clock with alarm, Johannes Reinbold, around 1600 (Inv. K-0473)

Neck clock with alarm, Johannes Reinbold, around 1600 (Inv. K-0473) Gold pocket watch, Balthasar de Paep, around 1600 (K-0458)

Gold pocket watch, Balthasar de Paep, around 1600 (K-0458) Pocket watch, L'Epine, around 1760 (K-0545)

Pocket watch, L'Epine, around 1760 (K-0545) "Revolution" pocket watch (Revolutionstaschenuhr), conventional and decimal display, around 1795 (K-0714)

"Revolution" pocket watch (Revolutionstaschenuhr), conventional and decimal display, around 1795 (K-0714) Finger ring with watch, around 1800 (Inv. K-1369)

Finger ring with watch, around 1800 (Inv. K-1369) Pocket chronometer, Friedrich Gutkaes, around 1820 (Inv. K-0746)

Pocket chronometer, Friedrich Gutkaes, around 1820 (Inv. K-0746) La Prolétaire pocket watch, Georges Frederic Roskopf, around 1870 (Inv. 2004-050)

La Prolétaire pocket watch, Georges Frederic Roskopf, around 1870 (Inv. 2004-050)

Highlights

Among the highlights of its permanent exhibits are:

- The late 20th century Hans Lang clock, a one-of-a-kind, ultra-complicated, astronomical clock[7]

- One of the earliest electrically impulsed pendulum clocks, by Alexander Bain (United Kingdom, ca. 1845)[8]

- The unique astronomical clock made in 1787 by Benedictine priest Thaddãus Rinderle at St. Peter's Abbey in the Black Forest[9]

- The monumental musical automaton clock of ca. 1880 by August Noll

- A mechanical orrery (planetarium) and a Weltmaschine by "Priestermechaniker" Philipp Matthäus Hahn[10]

- One of the early clocks (Paris, 1680) using a pendulum as a time standard, an invention of Christiaan Huygens

- Several large mechanical musical instruments (street organs )

- An extensive display documenting the history of the cuckoo clock and the many styles of cuckoo clocks made over time

- An easy-to-follow but comprehensive display outlining the history of the wristwatch[11]

Tourism and visitors

Around one third of visitors book a personal guided tour during which clocks and musical instruments are set in motion. Especially during the holidays children may build and decorate a clock in the "clock workshop". For school classes, the museum offers themed workshops in modules, some of which are designed to match the education syllabus. The collection has 8,000 items and about 1,300 clocks are permanently displayed. As well as clocks, the collection includes a company documents archive and a specialist library of German-language literature.

In 2006, the museum was one of 365 places selected to represent Germany in the federal chancellor's competition Land of Ideas. In 2008, the museum was awarded the distinction of being an "anchor point on the European Route of Industrial Heritage". At the same time, the museum became a milestone on the German Clock Road that links places in the region associated with clockmaking.

In 2010, the museum had 60,000 visitors.

Similar museums

- Cuckooland Museum (Tabley, England)

- Mussee Internationale d'Horlogerie (La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland)

- Dorf- und Uhrenmuseum (Gütenbach, Germany)

- National Watch and Clock Museum (Lancaster, Pennsylvania, United States)

- Museum für Uhren und mechanische Musikinstrumente (Oberhofen am Thunersee, Switzerland)

- Royal Observatory, Greenwich (Greenwich, London, England)

- Museum Speelklok (Utrecht, The Netherlands)

- Przypkowscy Clock Museum (Jedrzejow, Poland)

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ "The German Clock Museum". Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ↑ German Clock Museum at deutsches-uhrenmuseum.de. Accessed on 31 Mar 11.

- ↑ "Museum – Deutsches Uhrenmuseum". www.deutsches-uhrenmuseum.de. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ↑ Furtwangen, Hochschule. "German Clock Museum | Central services". Furtwangen University. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ↑ Ausführlich zur Geschichte des Museums: Simone von der Geest: "Aufbewahren und Versinnlichen", Das Deutsche Uhrenmuseum Furtwangen entwickelt sich seit 150 Jahren. Museum Aktuell, September 2002, pp. 3583–3586.

- ↑ "Permanent Exhibition – Deutsches Uhrenmuseum". www.deutsches-uhrenmuseum.de. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ↑ Lange, Juergen; Richard Muehe (1995). Die Hans-Lang Uhr – Sonderausstellung im Deutschen Uhrenmuseum Furtwangen. Furtwangen: Deutsches Uhrenmuseum. p. 32.

- ↑ Graf, Johannes (2006). Modern Times – Timekeeping on its way to the present. Furtwangen: Deutsches Uhrenmuseum. p. 40. ISBN 3-922673-19-8.

- ↑ Wenzel, Johann (2006). Die astronomisch-geographische Uhr von Pater Thaddãus Rinderle, im Anhang eine kurze Geschichte der Uhr, sowie ein Facsimile und die Transdskription von Thaddaeus Rinderles eigenhaendiger Beschreibung der Uhr durch Eberhard Marthe. Furtwangen: Deutsches Uhrenmuseum. p. 77. ISBN 3-922673-20-1.

- ↑ Haas, Carmen; Eduard Saluz (2007). A Brief History of Clock and Time. Furtwangen: Deutsches Uhrenmuseum. p. 40. ISBN 978-3-922673-23-1.

- ↑ Hundorf, Kathrin; Eduard Saluz (2004). A Brief History of the wristwatch. Furtwangen: Deutsches Uhrenmuseum. p. 40. ISBN 3-922673-16-3.

External links

- Official website (in German and English)