Danse macabre, Op. 40, is a symphonic poem for orchestra, written in 1874 by the French composer Camille Saint-Saëns. It premiered 24 January 1875. It is in the key of G minor. It started out in 1872 as an art song for voice and piano with a French text by the poet Henri Cazalis, based on the play Danza macàbra by Camillo Antona-Traversi.[1] In 1874, the composer expanded and reworked the piece into a symphonic poem, replacing the vocal line with a solo violin part.

Analysis

According to legend, Death appears at midnight every year on Halloween. Death calls forth the dead from their graves to dance for him while he plays his fiddle (here represented by a solo violin). His skeletons dance for him until the cockerel crows at dawn, when they must return to their graves until the next year.

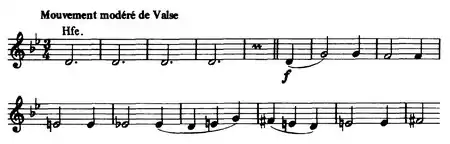

The piece opens with a harp playing a single note, D, twelve times (the twelve strokes of midnight) which is accompanied by soft chords from the string section. The solo violin enters playing the tritone, which was known as the diabolus in musica ("the Devil in music") during the Medieval and Baroque eras, consisting of an A and an E♭—in an example of scordatura tuning, the violinist's E string has actually been tuned down to an E♭ to create the dissonant tritone.

The first theme is heard on a solo flute,[2] followed by the second theme, a descending scale on the solo violin which is accompanied by soft chords from the string section.[3] The first and second themes, or fragments of them, are then heard throughout the various sections of the orchestra. The piece becomes more energetic and at its midpoint, right after a contrapuntal section based on the second theme,[4] there is a direct quote[5] played by the woodwinds of Dies irae, a Gregorian chant from the Requiem that is melodically related to the work's second theme. The Dies irae is presented unusually in a major key. After this section the piece returns to the first and second themes and climaxes with the full orchestra playing very strong dynamics. Then there is an abrupt break in the texture[6] and the coda represents the dawn breaking (a cockerel's crow, played by the oboe) and the skeletons returning to their graves.

The piece makes particular use of the xylophone to imitate the sounds of rattling bones. Saint-Saëns uses a similar motif in the Fossils movement of The Carnival of the Animals.

The progression and melody of the minor waltz are similar to the jibes (e.g. "their sweethearts all are dead") of the Sailors' Chorus in "Helmsman/Steersman, Leave Your Watch," which begins the third act of Wagner's earlier opera, "The Flying Dutchman".

Instrumentation

Danse macabre is scored for an obbligato violin and an orchestra consisting of one piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets in B♭, two bassoons; four horns in G and D, two trumpets in D, three trombones, one tuba; a percussion section that includes timpani, xylophone, bass drum, cymbals and triangle; one harp and strings.

Reception

When Danse macabre was first performed on January 24, 1875 it was not well received and caused widespread feelings of anxiety. The 21st century scholar, Roger Nichols, mentions adverse reaction to "the deformed Dies irae plainsong", the "horrible screeching from solo violin", the use of a xylophone, and "the hypnotic repetitions", in which Nichols hears a pre-echo of Ravel's Boléro.[7]

Today, it is considered one of Saint-Saëns' masterpieces, widely regarded and reproduced in both high and popular culture.

Transcriptions

Shortly after the premiere, the piece was transcribed into a piano solo arrangement by Franz Liszt (S.555),[8] a good friend of Saint-Saëns. Next to countless other piano solo transcriptions, Ernest Guiraud wrote a version for piano four hands and Saint-Saëns himself wrote a version for two pianos, and in 1877 also a version for violin and piano. In 1942, Vladimir Horowitz made extensive changes to the Liszt transcription. This version is played most often today.

There is an arrangement for Pierrot ensemble (flute, clarinet, violin, cello, piano) by Tim Mulleman, and an organ transcription by Edwin Lemare. Greg Anderson created a version for two pianos, two percussionists and violin, which he titled Danse Macbre Baccanale.

Usage

- This piece is played in Crowley's car as Aziraphale drives it from London to Edinburgh in Season 2, Episode 3 of the television show Good Omens. [9]

- This piece can be heard in the play performed at the end of the movie Shrek The Third.[10]

- The piece was later used in dance performances, including those of Anna Pavlova.[11]

- The piece is played offstage during the first act of Henrik Ibsen's 1896 play John Gabriel Borkman.

- The piece was used for the trailer of 1922 Swedish-Danish silent horror film Häxan.

- The piece is used as a recurring ironic motif in Jean Renoir's 1939 film The Rules of the Game (La Règle du Jeu),

- The music was heard in a 2002 Disney animated film Mickey's House of Villains and the 1999 Mickey Mouse Works episode titled Hansel and Gretel, starring Mickey Mouse & Minnie Mouse as the titular duo.

- An adaptation of the piece is used as the theme music for Jonathan Creek, a mystery crime series on British television.[12]

- The piece is used in the animated television series Modern Toss as the theme tune for the character Mr. Tourette – Master Signwriter.

- The piece is used in the Dutch theme park Efteling in the attraction Haunted Castle and its currently in-development successor Danse Macabre.

- It can be heard in Alone in the Dark after setting the record on the Gramophone in the Dance Hall.

- A portion of the piece can be heard in the 1993 western film Tombstone during the performance of the stage version of Faust.

- A synthesized version of the piece is used in the soundtrack for the anime television series Dimension W.

- In Neil Gaiman's novel The Graveyard Book the characters dance the "Macabray." In the audiobook, Danse macabre is played between chapters.

- The piece is also referenced in Neil Gaiman's book American Gods.

- American figure skater Timothy Goebel performed his short program to this piece during the 2001-02 season, including at the 2002 Winter Olympics, where he won the bronze medal.[13]

- Korean figure skater Yuna Kim used the piece as her short program music in 2008-2009 season.

- The piece is used in several instances during the 2011 Grimm episode "Danse Macabre", which is named after the piece.

- The 2011 film Hugo features the piece during a brief scene showing the history of early films.

- The piece is used as the ending theme of the Nickelodeon series Deadtime Stories.

- A looped part of the piece can be purchased as a vehicle horn in the 2013 video game Grand Theft Auto Online, only during Halloween event weeks.

- The piece can be heard during the New Year's Eve festivities in the 2014 gothic horror film, Stonehearst Asylum.

- The piece is used in the 2014 production "Immortal" by The Cavaliers Drum and Bugle Corps.

- The piece is played in the Buffy the Vampire Slayer episode "Hush", in which the character Rupert Giles plays the song while describing the episode's villains, the Gentlemen.

- The piece is arranged in multiple levels of The End is Nigh, such as "The End" and "Mortaman".

- The piece is used in the opening of Season 2 Episode 8 of the USA original, Mr. Robot.

- The piece is used in multiple episodes of the television series What We Do in the Shadows.

- The piece is used as a track in the Napoleonic Wars expansion pack for the game Mount & Blade: Warband by TaleWorlds Entertainment.

- The piece is used in the first episode of Don't F**k With Cats: Hunting an Internet Killer.

- The piece is used as the main theme for Ratched.

References

- ↑ Boyd, Malcolm. "Dance of death", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 6 October 2015. (subscription required)

- ↑ [IMSLP full score, page 3]

- ↑ [full score, page 4, 4th bar]

- ↑ [full score, page 13, rehearsal letter C]

- ↑ [full score, page 16, rehearsal letter D]

- ↑ [full score, page 50, 6th bar]

- ↑ Nichols, Roger (2012), Notes to Chandos CD CHSA 5104, OCLC 794163802

- ↑ Salle, Michael (2004). Franz Liszt: A Guide to Research. New York: Routledge. p. 460. ISBN 0-415-94011-7.

- ↑ "Good Omens (2023)". IMDb.

- ↑ "Shrek the Third (2007) - IMDb". IMDb.

- ↑ Garafola, Lynn (2005). Legacies of Twentieth-century Dance. New York: Wesleyan University Press. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-0-8195-6674-4.

- ↑ "A Danse Macabre". Classicfm.com. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ↑ "Timothy GOEBEL: 2002/2003". International Skating Union. Archived from the original on August 3, 2003.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)