| Conwy Castle | |

|---|---|

Castell Conwy | |

| Conwy, Wales | |

A view of the castle's massive defensive wall and the original gateway (right) | |

Conwy Castle | |

| Coordinates | 53°16′48″N 3°49′32″W / 53.28°N 3.825556°W |

| Type | Rectangular enclosure castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Cadw |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Website | cadw.gov.wales |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1283–89 |

| Built by | James of St. George |

| Materials | |

| Events |

|

| Part of | Castles and Town Walls of King Edward in Gwynedd |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, iv |

| Reference | 374 |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th Session) |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 1950 |

Conwy Castle (Welsh: Castell Conwy; Welsh pronunciation: [kastɛɬ 'kɔnwɨ̞]) is a fortification in Conwy, located in North Wales. It was built by Edward I, during his conquest of Wales, between 1283 and 1287. Constructed as part of a wider project to create the walled town of Conwy, the combined defences cost around £15,000, a massive sum for the period. Over the next few centuries, the castle played an important part in several wars. It withstood the siege of Madog ap Llywelyn in the winter of 1294–95, acted as a temporary haven for Richard II in 1399 and was held for several months by forces loyal to Owain Glyndŵr in 1401.

Following the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, the castle was held by forces loyal to Charles I, holding out until 1646 when it surrendered to the Parliamentary armies. In the aftermath, the castle was partially slighted by Parliament to prevent it being used in any further revolt, and was finally completely ruined in 1665 when its remaining iron and lead was stripped and sold off. Conwy Castle became an attractive destination for painters in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Visitor numbers grew and initial restoration work was carried out in the second half of the 19th century. In the 21st century, the ruined castle is managed by Cadw as a tourist attraction.

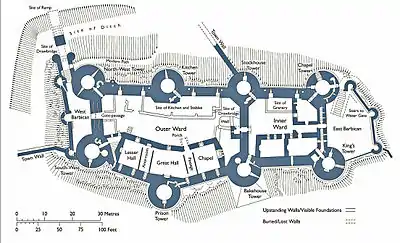

UNESCO considers Conwy to be one of "the finest examples of late 13th century and early 14th century military architecture in Europe", and it is classed as a World Heritage Site.[1] The rectangular castle is built from local and imported stone and occupies a coastal ridge, originally overlooking an important crossing point over the River Conwy. Divided into an Inner and an Outer Ward, it is defended by eight large towers and two barbicans, with a postern gate leading down to the river, allowing the castle to be resupplied from the sea. It retains the earliest surviving stone machicolations in Britain and what historian Jeremy Ashbee has described as the "best preserved suite of medieval private royal chambers in England and Wales".[2] In keeping with other Edwardian castles in North Wales, the architecture of Conwy has close links to that found in the Savoy during the same period, an influence probably derived from the Savoy origins of the main architect, James of Saint George.

History

13th century

Before the English built the town of Conwy, Aberconwy Abbey, the site was occupied by a Cistercian monastery favoured by the Welsh princes,[3] as well as the location of one of the palaces (called llys) of the Welsh princes. From Conwy: "the oldest structure is part of the town walls, at the southern end of the east side. Here one wall and the tower of a llys [palace/court house] belonging to Llywelyn the Great and his grandson Llywelyn ap Gruffydd have been incorporated into the wall. Built on a rocky outcrop, with an apsidal tower, it is a classic, native, Welsh build and stands out from the rest of the town walls, due to the presence of four window openings. It dates from the early 13th century and is the most complete remnant of any of his Llys."

The location also controlled an important crossing point over the River Conwy between the coastal and inland areas of North Wales, that Deganwy Castle for many years had defended.[3] The kings of England and the Welsh princes had vied for control of the region since the 1070s and the conflict had resumed during the 13th century, leading to Edward I intervening in North Wales for the second time during his reign in 1282.[4]

Edward invaded with a huge army, pushing north from Carmarthen and westwards from Montgomery and Chester. Edward captured Aberconwy in March 1283 and decided that the location would form the centre of a new county: he would relocate the abbey eight miles up the Conwy valley to a new site at Maenan, establishing Maenan Abbey, and build a new English castle and walled town on the monastery's former site.[5] The ruined castle of Deganwy was abandoned and never rebuilt.[6] Edward's plan was a colonial enterprise and placing the new town and walls on top of such a high-status native Welsh site was in part a symbolic act to demonstrate English power.[7]

Work began on cutting the ditch around Conwy Castle within days of Edward's decision.[8] The work was controlled by Sir John Bonvillars and overseen by master mason James of St. George, and the first phase of work between 1283 and 1284 focused on creating the exterior curtain walls and towers.[9] In the second phase, from 1284 and 1286, the interior buildings were erected, while work began on the walls for the neighbouring town.[10] By 1287, the castle was complete.[10] The builders recruited huge numbers of labourers from across England for the task. At each summer building season, the labourers massed at Chester and then walked into Wales.[11] Edward's accountants did not separate the costs of the town walls from that of the castle, but the total cost of the two projects came to around £15,000, a huge sum for the period.[10][nb 1]

The castle's constable was, by a royal charter of 1284, also the mayor of the new town of Conwy (to this day, the Mayor is ex-officio Constable of the Castle), and oversaw a castle garrison of 30 soldiers, including 15 crossbowmen, supported by a carpenter, chaplain, blacksmith, engineer and a stonemason.[13] The first constable of the castle was Sir William de Cicon who had previously been the first constable of Rhuddlan Castle. In 1294 Madog ap Llywelyn rebelled against English rule. Edward was besieged at Conwy by the Welsh between December and January 1295, supplied only by sea, before forces arrived to relieve him in February.[14] Chronicler Walter of Guisborough suggested that given the austere conditions Edward refused to drink his own private supply of wine, and instead had it shared out amongst the garrison.[15] For some years afterwards, the castle formed the main residence for visiting senior figures, and hosted Edward's son, the future Edward II in 1301 when he visited the region to receive homage from the Welsh leaders.[16]

14th–15th centuries

Conwy Castle was not well maintained during the early 14th century and by 1321 a survey reported it was poorly equipped, with limited stores and suffering from leaking roofs and rotten timbers.[17] These problems persisted until Edward, the Black Prince, took over control of the castle in 1343.[17] Sir John Weston, his chamberlain, conducted repairs, building new stone support arches for the great hall and other parts of the castle.[17] After the death of the Black Prince, however, Conwy fell into neglect again.[17]

At the end of the 14th century, the castle was used as a refuge by Richard II from the forces of his rival, Henry Bolingbroke.[18] On 12 August 1399, after returning from Ireland, Richard made his way to the castle where he met Bolingbroke's emissary, Henry Percy, for negotiations.[19] Percy swore in the chapel he would not harm the king. On 19 August, Richard surrendered to Percy at Flint Castle, promising to abdicate if his life were spared.[20] The king was then taken to London and died later in captivity at Pontefract Castle.[19]

Henry Bolingbroke took the English throne to rule as Henry IV in 1400, but rebellion broke out in North Wales shortly afterwards under the leadership of Owain Glyndŵr.[19] In March 1401, Rhys ap Tudur and his brother Gwilym, cousins of Owain Glyndŵr, undertook a surprise attack on Conwy Castle.[19] Pretending to be carpenters repairing the castle, the two gained entry, killed the two watchmen on duty and took control of the fortress.[19] Welsh rebels then attacked and captured the rest of the walled town.[21] The brothers held out for around three months, before negotiating a surrender; as part of this agreement the pair were given a royal pardon by Henry.[19]

During the War of the Roses between 1455 and 1485, fought by the rival factions of the Lancastrians and the Yorkists, Conwy was reinforced but played little part in the fighting.[22] Henry VIII conducted restoration work in the 1520s and 1530s, during which time the castle was being used as a prison, a depot and as a potential residence for visitors.[22]

17th–21st centuries

Conwy Castle fell into disrepair again by the early 17th century.[23] Charles I sold it to Edward Conway in 1627 for £100, and Edward's son, also called Edward, inherited the ruin in 1631.[23][nb 2] In 1642 the English Civil War broke out between the Charles' royalist supporters and Parliament.[23] John Williams, the Archbishop of York, took charge of the castle on behalf of the king, and set about repairing and garrisoning it at his own expense.[23] In 1645, Sir John Owen was appointed governor of the castle instead, however, leading to a bitter dispute between the two men.[25] The Archbishop defected to Parliament, the town of Conwy fell in August 1646 and in November General Thomas Mytton finally took the castle itself after a substantial siege.[26] The Trevor family petitioned Mytton for the return of property in the castle that they had lent to the Archbishop.[27]

In the aftermath of the siege, Colonel John Carter was appointed governor of the castle and fresh repairs were carried out.[26] In 1655 the Council of State appointed by Parliament ordered the castle to be slighted, or put beyond military use: the Bakehouse tower was probably deliberately partially pulled down at this time as part of the slighting.[26] With the restoration of Charles II in 1660, Conway was returned to Edward Conway, the Earl of Conway, but five years later Edward decided to strip the remaining iron and lead from the castle and sell it off.[28] The work was completed under the supervision of Edward Conway's overseer William Milward, despite opposition from the leading citizens of Conwy, and turned the castle into a total ruin.[29]

By the end of the 18th century, the ruins were considered picturesque and sublime, attracting visitors and artists, and paintings of the castle were made by Thomas Girtin, Moses Griffith, Julius Caesar Ibbetson, Paul Sandby and J. M. W. Turner.[29] Several bridges were built across the River Conwy linking the town and Llandudno during the 19th century, including a road bridge in 1826 and a rail bridge in 1848. These improved communication links with the castle and further increased tourist numbers.[30] In 1865 Conwy Castle passed from the Holland family, who had leased it from the descendants of the Conways to the civic leadership of Conwy town. Restoration work on the ruins then began, including the reconstruction of the damaged Bakehouse tower.[30] In 1953 the castle was leased to the Ministry of Works and Arnold Taylor undertook a wide range of repairs and extensive research into the castle's history.[31] An additional road bridge was built to the castle in 1958.[30] Already protected as a scheduled monument, in 1986 it was also declared part of the World Heritage Site of the "Castles and Town Walls of King Edward in Gwynedd".[32]

In the 21st century the castle is managed by Cadw as a tourist attraction and 186,897 tourists visited the castle in 2010; a new visitor centre was opened in 2012.[33] The castle requires ongoing maintenance and repairs cost £30,000 over the 2002–03 financial year.[34]

Conwy Castle was twinned with Himeji Castle, Hyogo prefecture, Japan at a formal ceremony in Himeji on 29 October 2019.[35]

In December 2023, Condé Nast voted the castle as the most stunning in Europe, beating the likes of Eilean Donan in Scotland, and Kylemore Abbey in Ireland.[36]

Architecture

The castle hugs a rocky coastal ridge of grey sandstone and limestone, and much of the stone from the castle is largely taken from the ridge itself, probably when the site was first cleared.[37] The local stone was not of sufficient quality to be used for carving details such as windows, however, and accordingly sandstone was brought in from the Creuddyn peninsula, Chester and the Wirral.[38] This sandstone was more colourful than the local grey stone, and was probably deliberately chosen for its appearance.[38]

The castle has a rectangular plan and is divided into an Inner and Outer Ward, separated by a cross-wall, with four large, 70-foot (21 m) tall towers on each side; originally the castle would have been white-washed using a lime render.[39] The outside of the towers still have the putlog holes from their original construction, where timbers were inserted to create a spiralling ramp for the builders.[40] Although now somewhat decayed, the battlements originally sported triple finial designs and featured a sequence of square holes running along the outside of the walls.[41] It is uncertain what these holes were used for – they may have been drainage holes, supports for defensive hoarding or for displaying ornamental shields.[41]

The main entrance to the castle is through the western barbican, an exterior defence in front of the main gate.[42] When first built, the barbican was reached over a drawbridge and a masonry ramp that came up sharply from the town below; the modern path cuts east along the outside of the walls.[42] The barbican features the earliest surviving stone machicolations in Britain, and the gate would originally have been protected by a portcullis.[43]

The gate leads through to the Outer Ward which, when first built, would have been full of various administrative and service buildings.[44] The north-west tower was reached through the porter's lodge and contained limited accommodation and space for stores.[45] The south-west tower may have been used either by the castle's constable, or by the castle's garrison, and also contained a bakehouse.[45] On the south side of the ward is a range of buildings that included the great hall and chapel, sitting on top of the cellars, which are now exposed.[46] The stubs and one surviving stone arches from the 1340s can still be seen.[47] Behind the great hall was the tower used by the constable for detaining prisoners; this included a special room for holding prisoners, called the "dettors chambre" ("debtors' chamber") in the 16th century, and an underground dungeon.[48] On the north side of the ward was a range of service buildings, including a kitchen, brewhouse and bakehouse, backed onto by the kitchen tower, containing accommodation and storerooms.[49]

The Inner Ward was originally separated from the Outer Ward by an internal wall, a drawbridge and a gate, protected by a ditch cut into the rock.[50] The ditch was filled in during the 16th century and the drawbridge removed.[51] The spring-fed castle well built alongside the gate survives, and today is 91-foot (28 m) deep.[51] Inside, the ward contained the chambers for the royal household, their immediate staff and service facilities; today, historian Jeremy Ashbee considers them to be the "best-preserved suite of medieval private royal chambers in England and Wales".[2] They were designed to form a royal palace in miniature, that could, if necessary, be sealed off from the rest of the castle and supplied from the eastern gate by sea almost indefinitely, although in practice they were rarely used by the royal family.[52]

The royal rooms were positioned on the first floor of a range of buildings that ran around the outside of the ward, facing onto a courtyard.[53] The four towers that protected the Inner Ward contained service facilities, with the Chapel Tower containing the private royal chapel.[53] Each tower has an additional watchtower turret, probably intended both for security and to allow the prominent display of the royal flag.[54] The arrangement was originally similar to that of the 13th century Gloriette at Corfe Castle, and provided a combination of privacy for the king while providing extensive personal security.[55] The two sets of apartments were later unified into a single set of rooms, including a great chamber, outer chamber and inner chamber.[56]

On the east side of the Inner Ward is another barbican, enclosing the castle garden.[57] This was overlooked by the royal apartments, and changed in style over the years: in the early 14th century there was a lawn, in the late 14th century vines, in the 16th century crab-apple trees and a lawn and in the 17th century formal ornamental flowers.[58] A postern gate originally led down to the river where a small dock was built, allowing key visitors to enter the castle in private and for the fortress to be resupplied by boat, although this gate is now concealed by the later bridges built on the site.[59]

The architecture of Conwy has close to links to that found in the County of Savoy in the same period.[60] These include window styles, the type of crenellation used on the towers and positioning of putlog holes, and are usually ascribed to the influence of the Savoy architect Master James.[60] Notably the three pinnacled merlons are a feature seen at the Savoyard Castello San Giorio di Susa which had been visited by Edward on his way back from crusade in 1273.

Constable of the Castle

The official roles of the Constable were - Governor of the castle, governor of the fortified borough, keeper of the castle gaol (prison), Mayor (Latin: ex officio) and extraordinary duties.[61][62]

During 1283 the castle was recorded to have a garrison of : 30 men (Latin: Homines defensabiles), 15 cross-bowmen (Latin: Baslistarii), 1 superintendent at arms (Latin: Attilliator), 1 Chaplain (Latin: Capellanus), 1 Stone mason (Latin: Cementarius), 1 Carpenter (Latin: Carpentarius), 1 Artisan (Latin: Faber), 10 residents (Latin: Residuum), William De Sikun was the constable with a yearly fee of £190 (equivalent to £200,000 in 2021).[63][61]

List of Constables of Conwy Castle

This is the list of the constables of Conwy (Conway) castle and their reigning Monarchs from the Principality of Wales, the Kingdom of England and then the Commonwealth of England without hiatus until today's monarchy of Great Britain.[64]

- 1284 : William de Sikun

- 1292 : Thomas Brickdall

- 1297 : William de Archoleghweth

- 1300 : John de Havering

- 1302 : John de Clykum

- 1302 : Sir William de Sikun

- 1311 : William Bagot

- 1316 : William de Crealawe

- 1319 : Hugh Goddard

- 1320 : Henry de Wysshebury

- 1326 : William de Ercralewe

- 1326 : Roger de Mortuo (Roger Mortimer of Wigmore Castle)

- 1327 : Henry de Mortuo Mari (Henry Mortimer)

- 1330 : John Lestrange de Mudle

- 1337 : Edward de St. John Le Neven

- 1343 : Thomas D. Upton

- 1383 : John de Beauchamp

- 1399 : Sir Henry Percy

- 1403 : John de Bolde (Sir John Chandos)

- 1405 : John de Masey

- 1416 : Ralph Boteler

- 1461 : Sir Henry Bolde

- 1483 : Henry, Duke of Buckingham

- 1483 : Thomas Tunstall

- 1488 : Sir Richard Pole

- 1505 : Edward Salisbury

- 1512 : John Salisbury

- 1549 : Griffith John (Griffith ap John ap Robert)

- 1551 : Francis, Earl of Huntingdon

- 1552-3 : Maurice Wiliams, John Vaughan, Robert Evans.

- 1553 : John Herle

- 1574 : Robert Berry of Ludlow

- 1600 : Thomas Goodman

- 1605 : Sir Richard Herbert, Edward Herbert.

- 1627 : Edward Conway, 2nd Viscount Conway

- 1643 : John Williams (archbishop of York)

- 1645 : John Owen (Royalist)

- 1649 : Colonel John Carter

- 1661 : Edward, Lord Herbert of Cherbury

- 1679 : William, Lord Herbert of Cherbury

("A hiatus of nearly 100 years occurs here")

- 1769 : John Parry

- 1809 : Griffith ap Howel Vaughan of Rug

- 1848 : Thomas Price Lloyd

Gallery

See also

Notes and references

Explanatory notes

- ↑ It is impossible to accurately compare medieval and modern prices or incomes. For comparison, £15,000 is around twenty-five times the annual income of a 14th-century nobleman such as Richard le Scrope.[12]

- ↑ It is difficult to accurately compare 17th century and modern prices or incomes. Depending on the measure used, £100 could equate to between £15,200 to £3,180,000 in 2011 terms. For comparison, Henry Somerset, one of the richest men in England at the time, had an annual income of around £20,000.[24]

Citations

- ↑ "Castles and Town Walls of King Edward in Gwynedd". UNESCO. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- 1 2 Ashbee 2007, pp. 34–35

- 1 2 Ashbee 2007, p. 47

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 5; Taylor 2008, pp. 6–7

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 6

- ↑ Pounds 1994, pp. 172–173

- ↑ Creighton & Higham 2005, p. 101

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 7

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 8–9

- 1 2 3 Ashbee 2007, p. 9

- ↑ Brown 1962, pp. 123–125; Taylor 2008, p. 8

- ↑ Given-Wilson 1996, p. 157

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 27, 29

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 10; Brears 2010, p. 91

- ↑ Brears 2010, p. 91

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 10, 35

- 1 2 3 4 Ashbee 2007, p. 11

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 11–12

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ashbee 2007, p. 12

- ↑ "Richard II, King of England (1367–1400)". Luminarium.org. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 12–13

- 1 2 Ashbee 2007, p. 13

- 1 2 3 4 Ashbee 2007, p. 14

- ↑ "Measuring Worth Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to Present". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 12 September 2012.; Pugin 1895, p. 23

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 14–15

- 1 2 3 Ashbee 2007, p. 16

- ↑ Hamilton, William Douglas. "Charles I - volume 514: October 1646 Pages 474-485 Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Charles I, 1645-7. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1891". British History Online. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 15–16

- 1 2 Ashbee 2007, p. 17

- 1 2 3 Ashbee 2007, p. 18

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 19

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 19; "Attractions Industry News". Association of Leading Visitor Attractions. Retrieved 12 September 2012.; "Gwynedd Destination and Marketing Audit" (PDF). Gwynedd Council. p. 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ↑ "Part 2: Significance and Vision" (PDF). Cadw. p. 56. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ↑ "Conwy and Himeji castles' twinning starts 'beautiful friendship'". BBC News. 7 November 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ "The castle voted Europe's most beautiful is in Wales". nation.cymru. 28 December 2023.

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 21; Lott 2010, p. 115

- 1 2 Lott 2010, p. 115

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 21, 24; Lepage 2012, p. 210

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 22

- 1 2 Ashbee 2007, p. 23

- 1 2 Ashbee 2007, pp. 24–25

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 25

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 26

- 1 2 Ashbee 2007, p. 27

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 28–29

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 30

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 29–31

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 31–32

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 32–33

- 1 2 Ashbee 2007, p. 33

- ↑ Brears 2010, p. 86; Ashbee 2007, p. 35

- 1 2 Ashbee 2007, p. 34

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 21

- ↑ Ashbee 2010, p. 83; Brears 2010, p. 86

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 35

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 43

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, p. 43; Ashbee 2010, p. 77

- ↑ Ashbee 2007, pp. 43–44

- 1 2 Coldstream 2010, pp. 39–40

- 1 2 Lewis, Edward Arthur (April 1912). The Mediæval boroughs of Snowdonia; a study of the rise and development of the municipal element in the ancient principality of North Wales down to the Act of union of 1536. Series of literary and historical studies,no. 1. Cornell University Press. pp. 47, 122.

- ↑ Lowe 1912, pp. 190–192.

- ↑ United Kingdom Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth "consistent series" supplied in Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2018). "What Was the U.K. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ↑ Rickard, John (2002). The Castle Community: The Personnel of English and Welsh Castles, 1272–1422. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 111–113. ISBN 0-85115-913-3.

General bibliography

- Ashbee, Jeremy (2007). Conwy Castle. Cardiff, UK: Cadw. ISBN 978-1-85760-259-3.

- Ashbee, Jeremy (2010). "The King's Accommodation at his Castles". In Williams, Diane; Kenyon, John (eds.). The Impact of Edwardian Castles in Wales. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books. pp. 72–84. ISBN 978-1-84217-380-0.

- Brears, Peter (2010). "Food Supply and Preparation at the Edwardian Castles". In Williams, Diane; Kenyon, John (eds.). The Impact of Edwardian Castles in Wales. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books. pp. 85–98. ISBN 978-1-84217-380-0.

- Brown, R. Allen (1962). English Castles. London, UK: Batsford. OCLC 1392314.

- Coldstream, Nicola (2010). "James of St George". In Williams, Diane; Kenyon, John (eds.). The Impact of Edwardian Castles in Wales. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books. pp. 37–45. ISBN 978-1-84217-380-0.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton; Higham, Robert (2005). Medieval Town Walls: An Archaeology and Social History of Urban Defence. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-1445-4.

- Given-Wilson, Chris (1996). The English Nobility in the Late Middle Ages. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-44126-8.

- Lepage, Jean-Denis G. G. (2012). British Fortifications Through the Reign of Richard III: an Illustrated History. Jefferson, NC, US: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5918-6.

- Lott, Graham (2010). "The Building Stones of the Edwardian Castles". In Williams, Diane; Kenyon, John (eds.). The Impact of Edwardian Castles in Wales. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books. pp. 114–120. ISBN 978-1-84217-380-0.

- Lowe, Walter Bezant (1912). The Heart of Northern Wales: As it was and as it Is, Being an Account of the Pre-historical and Historical Remains of Aberconway and the Neighbourhood. Vol. 1. p. 187-328.The heart of North Wales at Google Books

- Pounds, Norman John Greville (1994). The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Pugin, Augustus (1895). Examples of Gothic Architecture Selected From Various Ancient Edifices in England. Edinburgh, UK: J. Grant. OCLC 31592053.

- Taylor, Arnold (2008). Caernarfon Castle and Town Walls. Cardiff, UK: Cadw. ISBN 978-1-85760-209-8.

External links

- Cadw's official page on Conwy Castle

- Conwy Castle is depicted on the mug from Starbucks' You Are Here series

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)