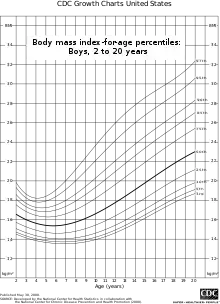

BMI for age percentiles for boys 2 to 20 years of age |

BMI for age percentiles for girls 2 to 20 years of age |

Development of tools for monitoring growth

Defining the parameters for childhood obesity has created substantial public awareness over the past decades. Stuart/Meredith Growth Charts were among the earliest growth charts widely used in the United States but were limited by not being representative of the entire US pediatric population.[1] Consequently, the need to develop growth charts that would encompass the ethnic, genetic, socioeconomic, environmental, and geographic diversity in the United States began in the 1970s.[1] In 1977, new growth charts were developed by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) based on data collected by the National Health Examination Surveys. However, these still contained many limitations and revised versions, as new information became available.[1] The 2000 CDC growth charts - a revised version of the 1977 NCHS growth charts - are the current standard tool for health care providers and offer 16 charts (8 for boys and 8 for girls), of which BMI-for-age is commonly used for aiding in the diagnoses of childhood obesity.[1]

In 2004, the World Health Organization began planning new growth chart references that could be used in all countries based on the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS) (1997–2003).[2] The MGRS was a multifaceted study which gathered data from 8,500 children from widely differing ethnic backgrounds and cultural settings.[2] The MGRS focused on describing growth pattern of children who followed recommended health practices and behaviors associated with healthy outcomes.[3] Upon recollection of data from MGRS, in 2007, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched gender specific height-for-age and BMI-for-age charts for 5- to 19-year-olds (upper limit of adolescence as defined by WHO).[2] BMI-for-age, along with height-for-age, is the WHO recommended charts for assessing thinness, overweight, and obesity in school-aged children and adolescents.[4]

Defining obesity

According to both the WHO and CDC, BMI growth charts for children and teens are sensitive to both age-and sex-specific groups, justified by the differences in body fat between sexes and among different age groups.[5] The CDC BMI-for-age growth charts use age-and-gender specific percentiles to define where the child or teenagers stands as compared to the population standard to define overweight and obese categories.[5] A public measure is one's socioeconomic status, which is determined by taking a group of peers and comparing characteristics like logistical differences, household income, parental occupations, and individual health into consideration. These factors are then used to categorize people into a social group and link them to the likelihood of being overweight or obese.[6] For the CDC, a BMI greater than the 85th percentile but less than the 95th percentile is considered overweight, and a BMI of greater than or equal to the 95th percentile is considered obese.[5] WHO parameters for BMI-for-age parameters are defined by standard deviations and describe overweight to be greater than +1standard deviation from the mean (equivalent to BMI=25 kg/m2 at 19 years) and obese as +2 standard deviations from the mean for 5 to 19 year-olds (equivalent to BMI=30 kg/m2 at 19 years).[7]

Furthermore, over the past years obesity rates have dramatically increased worldwide. Statistics from across the globe demonstrate that approximately 22 million children under the age of five are classified as obese.[8] Some health risks associated with childhood obesity include high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. These factors may eventually lead to further complications such as heart attack, stroke, a variety of cardiovascular conditions and if not treated properly and in a timely manner may ultimately result in death. Data concluded from the Bogalusa Heart Study demonstrates that approximately 60 percent of overweight children five to ten years of age had at least one cardiovascular risk factor.[8] A few examples of other health risks include Blount's disease, skin fungal infections, Acanthosis Nigracans, Hepatic Steatosis, in addition to both psychological and behavioral problems.[8] Overweight children often struggle to maintain high self-esteem and experience both depression and anxiety.[8] Social stigma of obesity may also be a contributing factor to some of these negative health outcomes, as many fat children experience bullying related to their size. [9]

See also

- Bariatrics

- Obesity and walking

- Social stigma of obesity

- EPODE International Network, the world's largest obesity-prevention network

- World Fit A program of the United States Olympic Committee (USOC), and the United States Olympians and Paralympians Association (USOP)

- Bioelectrical impedance analysis – a method to measure body fat percentage.

- Body fat percentage

- Cellulite

- Human fat used as pharmaceutical in traditional medicine

- Starvation

- Steatosis (also called fatty change, fatty degeneration or adipose degeneration)

- Subcutaneous fat

References

- 1 2 3 4 Kuczmarski, Robert, Cynthia Ogden, Shumei Guo, Laurence Grummer Strawn, Katherine Flegal, Zuguo Mei, Rong Wei, Lester Curtin, Alex Roche, and Clifford Johnson. 2002. 2000 CDC growth charts for the united states: Methods and development. Vital and Health Statistics. Series 11, Data from the National Health Survey(246): 1-190.

- 1 2 3 Borghi, E., M. de Onis, C. Garza, J. Van den Broeck, E. A. Frongillo, L. Grummer-Strawn, S. Van Buuren, et al. 2006; 2005. Construction of the world health organization child growth standards: Selection of methods for attained growth curves Statistics in Medicine 25 (2): 247 <last_page> 265.

- ↑ Borghi, E., M. de Onis, C. Garza, J. Van den Broeck, E. A. Frongillo, L. Grummer-Strawn, S. Van Buuren, et al. 2006; 2005. Construction of the world health organization child growth standards: Selection of methods for attained growth curves Statistics in Medicine 25 (2): 247 <last_page>265.

- ↑ WHO | development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents [cited 12/10/2011 2011]. Available fromhttp://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/9/07-043497/en/index.html (accessed 12/10/2011).

- 1 2 3 Obesity and overweight for professionals: Childhood: Basics | DNPAO | CDC [cited 11/26/2011 2011]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/basics.html Archived 2017-07-19 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 11/26/2011).

- ↑ "Child Obesity and Socioeconomic Status." [cited 7/9/2014] Available from <http://www.noo.org.uk>.

- ↑ WHO | BMI-for-age (5-19 years) [cited 12/10/2011 2011]. Available fromhttp://www.who.int/growthref/who2007_bmi_for_age/en/index.html (accessed 12/10/2011).

- 1 2 3 4 , Deckelbaum, R. J. and Williams, C. L. (2001), Childhood Obesity: The Health Issue. Obesity Research, 9: 239S–243S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.125.

- ↑ Neilson, Susie (May 2019). "Teasing Kids About Their Weight May Make Them Gain More". NPR.