Grand Chief Henri Membertou | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1507 Southwestern St. Mary's Bay |

| Died | 18 September 1611 (aged 102/103) Port Royal, Canada |

| Occupation | Grand Chief of the Mi'kmaq people |

| Years active | 1550-1611 |

| Title | sakmow (Grand Chief) |

Chief Henri Membertou (1507 – 18 September 1611) was the sakmow (Grand Chief) of the Mi'kmaq First Nations tribe situated near Port Royal, site of the first French settlement in Acadia, present-day Nova Scotia, Canada. Originally sakmow of the Kespukwitk district, he was appointed as Grand Chief by the sakmowk of the other six districts. Membertou claimed to have been a grown man when he first met Jacques Cartier, which makes it likely that he was born in the early years of the sixteenth century.[1][2]

Biography

Pre-baptism

Before becoming grand chief, Membertou had been the District Chief of Kespukwitk, a part of the Mi'kmaq nation which included the area where the French colonists settled Port-Royal.[3] In addition to being sakmow or political leader, Membertou had also been the head autmoin or spiritual leader of his tribe – who believed him to have powers of healing and prophecy.

Membertou was known to have acquired his own French shallop which he decorated with his own totems. He used this ship to trade with Europeans far out at sea, gaining first access to this important market and allowing him to sell goods at more worthwhile exchanges ("forestalling the market").[4]

Membertou became a good friend to the French. He first met the French when they arrived to build the Habitation at Port-Royal in 1605, at which time, according to the French lawyer and author Marc Lescarbot, he said he was over 100 and recalled meeting Jacques Cartier in 1534.[5]

Both Lescarbot and explorer Samuel de Champlain wrote of having witnessed him conducting a funeral in 1606 for Panoniac, a fellow Mi'kmaw sakmow who had been killed by the Armouchiquois or Passamaquoddy tribe, of what is now Maine. Seeking revenge for this and similar acts of hostility, Membertou led 500 warriors in a raid on the Armouchiquois town, Chouacoet, present-day Saco, Maine, in July, 1607, killing 20 of their people, including two of their leaders, Onmechin and Marchin.[6]

He is described by the Jesuit Pierre Biard as having maintained a beard, unlike other Mi'kmaq males who removed all facial hair. He was larger than the other males and despite his advanced age, had no grey or white hair.[1] Also, unlike most sakmowk who were polygamous, Membertou had only one wife, who was baptised with the name of "Marie". Lescarbot records that the eldest son of Chief Membertou had the name Membertouchis (Membertouji'j, baptised Louis Membertou after the then-King of France, Louis XIII), while his second and third sons were called Actaudin (absent at the time of the baptism) and Actaudinech (Actaudinji'j, baptised Paul Membertou). He also had a daughter, given the name Marguerite.

After building their fort, the French left in 1607, leaving only two of their party behind, during which time Membertou took good care of the fort and them, meeting them upon their return in 1610.

Baptism

On 24 June 1610 (Saint John the Baptist Day), Membertou became the first native leader to be baptised by the French, as a sign of alliance and good faith. The ceremony was carried out by priest Jessé Fléché, who went on to baptize all 21 members of Membertou's immediate family.[7][8][9] It was then that Membertou was given the baptismal name Henri, after the late king of France, Henry IV.[1] Membertou's Baptism was part of the entry by the Mi'kmaq into a relationship with the Catholic Church, known as the Mi'kmaw Concordat.[10]

Post-baptism

Membertou was very eager to become a proper Christian as soon as he was baptized. He wanted the missionaries to learn the Algonquian Mi'kmaq language so that he could be properly educated.[1] Biard relates how, when Membertou's son Actaudin became gravely ill, he was prepared to sacrifice two or three dogs to precede him as messengers into the spirit world, but when Biard told him this was wrong, he did not, and Actaudin then recovered. However, in 1611, he contracted dysentery, one of the many infectious diseases spread in the New World by Europeans. By September 1611, he was very ill. Membertou insisted on being buried with his ancestors, something that bothered the missionaries. However; Membertou soon changed his mind and requested to be buried among the French. He died on 18 September 1611.[1] In his final words, he charged his children to remain devout Christians.

In 2007 Canada Post issued a $0.52 stamp (domestic rate) in its "French Settlement in North America" series in honour of Chief Membertou.

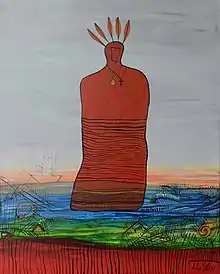

A portrait of Membertou painted by the noted Mi'kmaq artist, Alan Syliboy, was presented to Queen Elizabeth II during the 2010 Royal Tour of Canada. The portrait is on permanent display at Government House (Nova Scotia).[11]

Songs

Three songs of Membertou survive in written form, and provide the first music transcriptions from the Americas. The melodies for the songs were transcribed in solfège notation by Marc Lescarbot.[12] The time values of each note were recorded in an arrangement of Membertou's songs in mensural notation by Gabriel Sagard-Théodat.[13]

The melodies use three notes of the solfege scale – originally transcribed as Re-Fa-Sol by Lescarbot, but more easily sung as La-Do-Re. Transcriptions of these songs are available for Native American flute.[14]

See also

- List of grand chiefs (Mi'kmaq)

- Order of Good Cheer

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bumsted, J. M. (2007). A History of the Canadian Peoples. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-542349-5.

- ↑ "Mi'kmaq Grand Chiefs" (PDF). hrsbstaff.ednet.ns.ca. 3 December 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ↑ Paul, Daniel N. (2000). We Were Not the Savages: A Mi'kmaq Perspective on the Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations (2nd ed.). Fernwood. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-55266-039-3.

- ↑ Fischer, David Hackett (2009). Champlain's Dream. Vintage Canada. pp. 159, 219. ISBN 978-0-307-37301-4.

- ↑ "Canada Post - Collecting". Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "Messamouet (?-1610?)". Encyclopedia.com.

- ↑ Augustine, Stephen J. (9 September 1998). A Culturally Relevant Education for Aboriginal Youth: Is there room for a middle ground, accommodating Traditional Knowledge and Mainstream Education? (PDF) (Masters of Arts, School of Canadian Studies thesis). Ottawa, Ontario: Carleton University. p. 9. Retrieved 8 August 2016. Citing Wallis and Wallis

- ↑ Wallis, Wilson D.; Wallis, Ruth Sawtell (1955). The Micmac Indians of Eastern Canada. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8166-6014-8.

- ↑ Prins, Harald E. L. (1996). The Miʼkmaq: Resistance, Accommodation, and Cultural Survival. Harcourt Brace. pp. 35, 53. ISBN 978-0-03-053427-0.

- ↑ Henderson, James (Sákéj) Youngblood (1997). The Míkmaw Concordat. Fernwood. ISBN 978-1-895686-80-7.

- ↑ McCreery, Christopher (2020). Government House Halifax: A Place of History and Gathering. Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions. ISBN 978-1773102016.

- ↑ Lescarbot, Marc (1617). Histoire de la Nouvelle-France [History of New France – Third Edition] (in French) (Troisième ed.). Paris: Ardian Perier – via Project Gutenberg Ebook #22268.

- ↑ Sagard Théodat, Gabriel (1866). Histoire du Canada et voyages que les frères mineurs recollects y ont faicts pour la conversion des infidèles depuis l'an 1615: Avec un dictionnaire de la langue huronne... (in French) (Deuxième Partie ed.). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Goss, Clint (24 March 2018). "Membertou's Three Songs – Sheet Music for Native American Flute". Flutopedia. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

Bibliography

- Thierry, Éric (2008). La France de Henri IV en Amérique du nord: de la création de l'Acadie à la fondation de Québec. Paris: Champion. ISBN 978-2-7453-1758-2.

- Campeau, Lucien (1979) [1966]. [tp://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/membertou_1E.htm "Membertou (baptized Henri)"]. In Brown, George Williams (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.