| Eastern pygmy possum[1] Temporal range: Late Pleistocene – Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Burramyidae |

| Genus: | Cercartetus |

| Species: | C. nanus |

| Binomial name | |

| Cercartetus nanus (Desmarest, 1818) | |

| |

| Eastern pygmy possum range | |

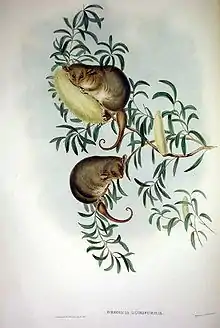

The eastern pygmy possum (Cercartetus nanus) is a diprotodont marsupial of south-eastern Australia. Occurring from southern Queensland to eastern South Australia and also Tasmania,[1] it is found in a range of habitats, including rainforest, sclerophyll forest, woodland and heath.

Taxonomy and nomenclature

The eastern pygmy possum is the type species of the genus Cercartetus (family Burramyidae), and was first described as Phalangista nana with the specific name meaning 'dwarf' in Latin. Currently, the authority for the specific name is widely accepted as Desmarest 1818, but in a review recently published, it was pointed out that an earlier version of Desmarest's account was published in 1817.[3]

Names synonymous with Cercartetus nanus are Phalangista glirifomis (Bell, 1828) and Dromicia britta (Wood Jones, 1925).[1] These coincide with the two subspecies C. n. nanus (Desmarest, 1818) (the Tasmanian subspecies) and C. n. unicolor (Krefft, 1863) (the mainland Australian subspecies).[1]

Vernacular names that have been used for this species include dwarf phalanger, minute phalanger, dwarf cuscus, pigmy phalanger, Bell's Dromicia, opossum mouse, dusky Dromicia, pygmy opossum, thick-tailed Dromicia, mouse-like phalanger, common dormouse-phalanger, dormouse phalanger, common dormouse-opossum, dormouse possum, pigmy opossum, pigmy possum and eastern pigmy possum.[3] A standard name finally arose via a committee of the Australian Mammal Society.[4]

Description

Eastern pygmy possums are very small, weighing from 15 to 43 grams (0.53 to 1.52 oz) and having a body length of between 7 and 9 centimetres (2.8 and 3.5 in) with a 8 to 11 centimetres (3.1 to 4.3 in) tail. They are dull grey above and white below, with big, forward pointing, almost hairless, ears and a long prehensile tail, with thick fur at the base that becomes sparser towards the tip. They have long whiskers, and a narrow ring of dark fur around each eye.[5]

The eastern pygmy possum is an active climber. It uses its brush tipped tongue to feed on nectar and pollen, especially from Banksia, Eucalyptus and Callistemon species.[6] It also feeds on insects, and will eat soft fruits when flowers are not available. It is a largely solitary animal, sheltering in tree hollows and stumps, abandoned bird nests, and thickets. During winter it spends time in torpor.[6]

They are nocturnal, and, although generally thought to be solitary, have been reported to share communal nests, and to be seen in groups of two or more adult individuals. Males occupy home ranges of 0.24 to 1.7 hectares (0.59 to 4.20 acres), which overlap with each other and with the smaller, 0.18 to 0.61 hectares (0.44 to 1.51 acres) ranges of females.[5]

Distribution and habitat

Eastern pygmy possums are found along the southeastern Australian coast, from eastern South Australia to southern Queensland, and on Tasmania. They inhabit shrubby vegetation in a wide variety of habitats, from open heathland or shrubland to sclerophyll or rainforest, at elevations from sea level to 1,800 metres (5,900 ft). Despite this apparent diversity of habitats, their distribution is patchy, and they are usually low in number where they are found.[5]

Reproduction

Eastern pygmy possums typically breed twice a year, although they may breed a third time if food is plentiful. Females have a well-developed pouch with four to six teats, and usually give birth to four young, although larger litters are not uncommon. Gestation lasts around 30 days, after which the young spend 33 to 37 days sheltering in the pouch. They are weaned at 60 to 65 days, and remain with the mother for at least a further ten days, by which time they weigh about 10 grams (0.35 oz).[5]

The young reach the full adult size at around five months, but may be able to breed as little as three months after birth. They live for up to 7.5 years in captivity, but probably no more than five years in the wild.[5]

Discovery

The first specimen of an eastern pygmy possum known to Europeans was collected by François Péron, a naturalist aboard Nicolas Baudin's voyage to the south seas.[3] Whilst on a short stay on Maria Island, off eastern Tasmania between 19 and 27 February 1802, Péron traded with the Aboriginal inhabitants for a single small marsupial. Péron wrote (in translation) 'In the class of mammiferous animals, I only saw one kind of Dasyurus, which was scarcely as large as a mouse. I obtained one that was alive, in exchange for a few trifles, from a savage who was just going to kill and eat it'.[7] In an unpublished manuscript (now held in the Le Havre Museum in France) Péron also wrote that the animal 'was given to me by the natives; it was still alive; I believe it to be a new species and have described it as Didelphis muroides because of its resemblance to the D. mus of Linnaeus'.[8] The specimen collected by Péron (a juvenile male) was transported back to France, and is now held in the Muséum National d’Historie Naturelle in Paris as the holotype.[9]

Fossil record

Bones of this species are often recorded as fossils or sub-fossils from late Pleistocene and Holocene cave deposits in south-eastern Australia. It is incorporated into the fossil record because owls and/or quolls that have preyed on eastern pygmy possums (and other small mammals) deposit regurgitated or faecal pellets in caves which then act as excellent preservation sites. About 50 such sites form the fossil record for the eastern pygmy possum.[10][11][12]

Conservation status

Eastern pygmy possums are listed as least concern by the IUCN,[2] and both subspecies are listed as lower risk by Australian Commonwealth Government legislation. At the State level within Australia, its status is defined variously. In New South Wales, it is considered vulnerable under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995. In South Australia, the species is considered vulnerable under Schedule 8 of that State's National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972. In Victoria, it is not listed under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988, and is therefore officially not threatened. Records for Queensland are scant, but the species is perhaps misleadingly classed as common under that State's Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulation 1994. In Tasmania, the eastern pygmy possum is currently considered not threatened under the Nature Conservation Act 2002.

Predators and parasites

Known predation records are by the barn owl Tyto alba, the masked owl T. novaehollandiae, the sooty owl T. tenebricosa, the barking owl Ninox connivens, the brown antechinus Antechinus stuartii, the tiger quoll Dasyurus maculatus, the Tasmanian devil Sarcophilus harrisii, the dingo Canis lupus dingo, the dog Canis lupus familiaris, the red fox Vulpes vulpes, the cat Felis catus, Stephen's banded snake Hoplocephalus stephensii, and the rough-scaled snake Tropidechis carinatus.[10][11][13][14] In a study of the impacts of logging on the species, conducted in McPherson State Forest, not far from Gosford, high rates of predation were found with six of 61 radio-tracked pygmy-possums taken by reptiles (tiger snakes, diamond pythons, and goannas) and two by raptors such as sooty owls with other predators such as native Antechinus and feral cats and foxes noted.[15] A sooty owl pellet investigation found that pygmy possums comprised 15% of the 126 dietary items identified.[15] The study's authors suggested that the species is vulnerable to altered predation regimes, such as influxes of feral predators, and highlights the need for a better understanding of any influence of logging on predator activity.[15]

Parasites recorded for the eastern pygmy possum are the fleas Acanthopsylla rothschildi, A. scintilla, Choristopsylla thomasi, and Ch. ochi; the mites Guntheria newmani, G. shieldsi, Ornithonyssus bacoti (normally a parasite of captive rats), and Stomatodex cercarteti (type described from C. nanus); two nematodes Tetrabothriostrongylus mackerrasae and Paraustrostrongylus gymnobelideus; and the common marsupial tick Ixodes tasmani. There is also a record of a free-living platyhelminth Geoplana sp., although this was possibly an accidental infection.[16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 Dickman, C.; Lunney, D.; Menkhorst, P. (2016). "Cercartetus nanus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T40578A21963504. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T40578A21963504.en.

- 1 2 3 Harris, J.M. (2006). "The discovery and early natural history of the eastern pygmy possum, Cercartetus nanus (Geoffroy and Desmarest, 1817)". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales. 127: 107–124.

- ↑ Strahan, R. (1981). A number of Australian mammal names: Pronunciation, derivation, and significance of the names, with bibliographical notes. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Harris, J.M. (2008). "Cercartetus nanus (Diprotodontia: Burramyidae)". Mammalian Species. 815: Number 185: pp. 1–10. doi:10.1644/815.1.

- 1 2 http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Cercartetus_nanus.html | University of Michigan Museum of Zoology: Animal Diversity Web

- ↑ Péron, M.F. (1975). A voyage of discovery to the southern hemisphere, performed by order of the Emperor Napoleon during the years 1801, 1802, 1803 and 1804. Melbourne: Marsh Walsh Publishing. p. 233.

- ↑ Observations zoologiques by François Péron, on Maria Island, unpublished manuscript # 18043:31.

- ↑ Julien-Laferriere, D (1994). Catalogue des types de mammiferes du Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle. Order des Marsupiaux. Extrait de Mammalia. Tome 58.

- 1 2 Harris, J. M.; Goldingay, R.L. (2005). "The distribution of fossil and sub-fossil records of the eastern pygmy-possum Cercartetus nanus in Victoria" (PDF). The Victorian Naturalist. 122: 160–170. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2009.

- 1 2 Harris, J. M.; Garvey, J.M. (2006). "Palaeodistribution of pygmy-possums in Tasmania". Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania. 140: 1–10. doi:10.26749/rstpp.140.1.

- ↑ Harris, J.M. (2006). "Fossil occurrences of Cercartetus nanus (Marsupialia: Burrmayidae) in South Australia". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia. 130 (2): 239–244. doi:10.1080/3721426.2006.10887063. S2CID 87706401.

- ↑ Bladon, R. V.; Dickman, C.R. & Hume, I.D. (2002). "Effects of habitat fragmentation on the demography, movements and social organisation of the eastern pygmy possum (Cercartetus nanus) in northern New South Wales". Wildlife Research. 29: 105–116. doi:10.1071/WR01024.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, M.; Shine, R. & Lemckert, F. (2004). "Life history attributes of the threatened Australian snake (Stephen's banded snake Hoplocephalus stephensii, Elapidae)". Biological Conservation. 119: 121–128. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2003.10.026.

- 1 2 3 Law, Bradley; Chidel, M.; Britton, A. (1 March 2013). "High predation risk for a small mammal: the eastern pygmy-possum (Cercartetus nanus)". Australian Mammalogy. 2. 35 (2): 149–152. doi:10.1071/AM12034. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ↑ Harris, J. M.; Vilcins, I. (2007). "Some parasites of the eastern pygmy possum, Cercartetus nanus (Marsupialia: Burramyidae)". Australian Mammalogy. 29: 107–110. doi:10.1071/am07015.