Catherine de' Medici was a patron of the arts made a significant contribution to the French Renaissance. Catherine was inspired by the example of her father-in-law, King Francis I of France (reigned 1515–1547), who had hosted the leading artists of Europe at his court. As a young woman, she witnessed at first hand the artistic flowering stimulated by his patronage.[1] As governor and regent of France, Catherine set out to imitate Francis's politics of magnificence. In an age of civil war and declining respect for the monarchy, she sought to bolster royal prestige through lavish cultural display.

After the death of her husband, Henry II, in 1559, Catherine governed France on behalf of her young sons King Francis II (1559–60) and King Charles IX (1560–74). Once in control of the royal purse, she launched a program of artistic patronage which lasted for three decades. She continued to employ Italian artists and performers, including the artist-architect Primaticcio. By the 1560s, however, a wave of home-grown talent—trained and influenced by the foreign masters brought to France by Francis—came to the fore. Catherine patronised these new artists and presided over a distinctive late French Renaissance culture. New forms emerged in literature, architecture, and the performing arts.[2] At the same time, as art historian Alexandra Zvereva suggests, Catherine became one of the great art collectors of the Renaissance.[3]

Although Catherine spent ruinous sums on the arts, the majority of her patronage had no lasting effect. The end of the Valois dynasty shortly after her death brought a change in priorities. Her collections were dispersed, her palaces sold, and her buildings were left unfinished or later destroyed. Where Catherine had made her mark was in the magnificence and originality of her famous court festivals. Today's ballets and operas are distantly related to Catherine de' Medici's court productions.[4]

Visual arts

An inventory drawn up at the Hôtel de la Reine after Catherine de' Medici's death shows that she was a keen collector of art and curiosities. Works of art included tapestries, hand-drawn maps, sculptures, and hundreds of pictures, many by Côme Dumoûtier and Benjamin Foulon, Catherine's last official painters. There were rich fabrics, ebony furniture inlaid with ivory, sets of china (probably from Bernard Palissy's workshop), and Limoges pottery. Curiosities included fans, dolls, caskets, games, pious objects, a stuffed chameleon, and seven stuffed crocodiles.[5]

By the time of Catherine's death in 1589, the Valois dynasty was in a terminal crisis; it became extinct with the death of Henry III only a few months later. Catherine's properties and belongings were sold off to pay her debts and dispersed with little ceremony. She had hoped for a far different posterity. In 1569, the Venetian ambassador had identified her with her Medici forebears: "One recognises in the queen the spirit of her family. She wishes to leave a legacy behind her: buildings, libraries, collections of antiquities".[3] Despite the destruction, loss, and fragmentation of Catherine's heritage, a collection of portraits formerly in her possession has been assembled at the Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly.

Portraits

The vogue for portrait drawings intensified during Catherine de' Medici's life, and she may have regarded part of her collection as the equivalent of today's family photograph album. Catherine loved having her children painted: "I would like", she wrote in 1547 to her children's governor, Jean d'Humières, "to have paintings of all the children done . . . and sent to me, without delay, as soon as they are finished".[6] However, the more formal pictures include a high proportion of portraits of European kings and queens, past and present, most of which she probably commissioned personally.[7] On 3 July 1571, Catherine wrote to Monsieur de la Mothe-Fénelon, ambassador in London, discussing the work of François Clouet and requesting a portrait of Queen Elizabeth. Catherine gave detailed instructions: "I pray you do me the pleasure that I may soon have a painting of the queen of England of small volume, in great [de la grandeur], and that it be well portrayed and done in the same fashion as the one sent be by the earl of Leicester, and ask, as I already have one in full face, it would be better to have her turning to the right."[8] The large group of portraits from Catherine's collection, now at the Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly, reveals her passion for the genre.[9] These include portraits by Jean Clouet (1480–1541) and by his son François Clouet (c. 1510–1572). Jean drew and painted in the style of the Italian High Renaissance, but in the portraits of François, a northern-European naturalism is apparent, and a flatter, more meticulous technique.[10]

François Clouet drew and painted portraits of all Catherine's family as well as of many members of the court. His drawing has been called profound, owing to its accuracy and harmony of form and its psychological penetration.[12] This tradition of court portraiture was carried on by Jean Decourt, Étienne, Côme, and Pierre Dumoûtier, and by the less polished Benjamin Foulon (François Clouet's nephew) and François Quesnel. The last two artists, plus another known as "Anonyme Lécurieux", tended to use a more stylised technique, producing flatter portraits, with less three-dimensional modelling.[13] After the death of Catherine de' Medici, a decline in the quality of portraiture set in; and by 1610, the native school patronised by the late Valois court and brought to its pinnacle by François Clouet had all but died out, and the Bourbon became reliant on foreign artists.[14]

Painting

Little is known about the painting at Catherine de' Medici's court.[15] In the last two decades of Catherine's life, only two painters stand out as recognisable personalities, Antoine Caron and Jean Cousin the Younger. The majority of paintings and portrait drawings that have survived from the late Valois period remain difficult or impossible to attribute to particular artists.

Antoine Caron became painter to Catherine de' Medici after working at Fontainebleau under Primaticcio. His vivid Mannerist style, with its love of ceremonial and allegory, perhaps reflects the peculiarly neurotic atmosphere of the French court during the Wars of Religion.[16] He adopted from Niccolò dell'Abbate the technique of elongated and twisted figures, placing them in spaces dominated by fantastical fragments of architecture borrowed from the drawings of Jacques Androuet du Cerceau and painted in surprising rainbow contrasts. The effect makes Caron's pin-headed figures appear puny and lost in the landscapes.[17]

Many of Caron's paintings, such as those of the Triumphs of the Seasons, are of allegorical subjects that echo the festivities for which Catherine's court was famous. His designs for the Valois Tapestries depict the fêtes, picnics, and mock battles of the "magnificent" entertainments for which Catherine was famous.[18] Caron often painted scenes of massacres, reflecting the background of civil war that cast a shadow over the magnificence of the court. Caron also painted astrological and prophetical subjects, such as Astrologers Studying an Eclipse and Augustus and the Sibyl. This theme may have been inspired by Catherine de' Medici's obsession with horoscopes and predictions.[17]

Jean Cousin, to judge by contemporary praise for his work, may have been as highly regarded at the time as Caron. The royal accounts show large payments made to Cousin: he was among those who decorated Paris for the entry of Henry II as king. Little of his work, however, survives. His most important surviving work is The Last Judgement in the Louvre, which like Caron's art, depicts human beings dwarfed by the landscape and, in Blunt's words, "made to swarm over the earth like worms".[17]

Tapestries

Missing from the inventory drawn up after Catherine's death were the eight huge tapestries, known as the Valois tapestries, now held at the Uffizi gallery in Florence, which depict "magnificences" such as those at Bayonne in 1565 during the summit meeting between the French and Spanish courts and the ball laid on at the Tuileries palace in 1573 by Catherine for the Polish envoys who offered the crown of their country to her son Henry of Anjou.[19] These magnificent hangings, originally designed during the reign of King Charles IX by Antoine Caron in the early 1570s,[20] were woven later in the Spanish Netherlands with additions, possibly designed by Lucas de Heere,[21] who worked for Catherine between 1559 and 1565,[22] that show fashions as late as 1580 and depict Henry III as king rather than Charles IX.[19]

Historian Frances Yates has suggested that these tapestries may have been produced in connection with the intervention of Catherine's son François, Duke of Anjou, who was elected duke of Brabant, in the Spanish Netherlands in 1580, in defiance of the Spanish administration. Anjou figures prominently in the tapestries. Catherine de’ Medici herself appears as a central figure in black in most of them.[23] It is believed that she gave them to her granddaughter Christina of Lorraine in advance of her wedding to Ferdinand de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1589.[23] The tapestries glorify the house of Valois by celebrating its magnificent festivals.[1]

Sculpture

According to the contemporary art historian Vasari, Catherine wanted Michelangelo to make her husband Henry II's equestrian statue; but Michelangelo passed the commission on to Daniele da Volterra, and only the horse was ever made.[24]

On commission from Catherine, Germain Pilon carved the marble sculpture that contains Henry II's heart. The Florentine Domenico del Barbiere, who had worked at Fontainebleau, carved the base. Pilon's fluid style echoes Primaticcio's stucco work at Fontainebleau. The piece may also have been influenced by Pierre Bontemps's monument for the heart of Francis I.[25] Pilon set the bronze urn on the heads of the Three Graces, who are poised back to back, as if to dance.[26] He may have based the design on that for an incense burner for Francis I, engraved by Marcantonio. Pilon's figures, however, with their long necks and small heads, are more like nymphs.[25] A poem by Ronsard is engraved at the foot of the sculpture. It asks the reader not to wonder that so small a vase can hold so large a heart, since Henry's real heart resides in Catherine's breast.[27] Henri Zerner has called the monument, which can be seen at the Louvre, "one of the summits of our sculpture".[28]

In the 1580s, Pilon began work on statues for the chapels that were to circle the tomb of Catherine de' Medici and Henry II at the basilica of Saint Denis. Among these, the fragmentary Resurrection, now in the Louvre, was designed to face the tomb of Catherine and Henry from a side chapel.[29] This work owes a clear debt to Michelangelo, who had designed the tomb and funerary statues for Catherine's father at the Medici chapels in Florence.[30] Pilon openly depicted extreme emotion in his work, sometimes to the point of the grotesque. His style has been interpreted as a reflection of a society torn by the conflict of the French wars of religion.[31]

Architecture

Architecture was Catherine de' Medici's first love among the arts. "As the daughter of the Medici", suggests French art historian Jean-Pierre Babelon, "she was driven by a passion to build and a desire to leave great achievements behind her when she died."[32] Having witnessed in her youth the huge architectural schemes of Francis I at Chambord and Fontainebleau, Catherine set out, after Henry II's death, to enhance the grandeur of the Valois monarchy through a series of costly building projects.[33] These included work on châteaux at Montceaux-en-Brie, Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, and Chenonceau, and the building of two new palaces in Paris: the Tuileries and the Hôtel de la Reine. Catherine was closely involved in the planning and supervising of all her architectural schemes.[34] Architects of the day dedicated treatises to her in the sure knowledge that she would read them.[35] The poet Ronsard accused her of preferring masons to poets.[36]

Catherine was intent on immortalising her sorrow at the death of her husband and had emblems of her love and grief carved into the stonework of her buildings.[38] As the centrepiece of an ambitious new chapel, she commissioned a magnificent tomb for Henry at the basilica of Saint Denis, designed by Francesco Primaticcio. In a long poem of 1562, Nicolas Houël, laying stress on her love for architecture, likened Catherine to Artemisia, who had built the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, as a tomb for her dead husband.[39] Primaticcio's circular plan for the Valois chapel, by allowing the tomb to be viewed from all angles, solved the problems faced by the Giusti brothers and Philibert de l'Orme, builders of previous royal tombs.[40] Art historian Henri Zerner has called the design "a grand ritualistic drama which would have filled the rotunda's celestial space" and "the last and most brilliant of the royal tombs of the Renaissance".[41] Work on the building was abandoned in 1585, as the monarchy faced bankruptcy and a series of rebellions. Over two hundred years later, in 1793, a mob tossed Catherine and Henry's bones into a pit with the rest of the French kings and queens.[42]

Catherine de' Medici spent extravagant sums on the building and embellishment of monuments and palaces, and as the country slipped deeper into anarchy, her plans grew ever more ambitious.[43] Yet the Valois monarchy was crippled by debt and its moral authority in steep decline. The popular view condemned Catherine's building schemes as obscenely wasteful. This was especially true in Paris, where the parlement was often asked to contribute to her costs.

Ronsard captured the mood in a poem:

- The queen must cease building,

- Her lime must stop swallowing our wealth…

- Painters, masons, engravers, stone-carvers

- Drain the treasury with their deceits.

- Of what use is her Tuileries to us?

- Of none, Moreau; it is but vanity.

- It will be deserted within a hundred years.[44]

Ronsard was in many ways proved correct. Little remains of Catherine de' Medici's investment today: one Doric column, a few fragments in the corner of the Tuileries gardens, an empty tomb at Saint Denis.

Literature

Catherine believed in the humanist ideal of the learned Renaissance prince whose power depended on letters as well as arms, and she was familiar with the writing of Erasmus, among others, on the subject.[45] She enjoyed and collected books, and moved the royal collection to the Louvre, her principal residence. She delighted in the company of learned men and women, and her court was highly literary. Her government officials, such as secretary-of-state Nicolas de Neufville, seigneur de Villeroy, whose wife translated the epistles of Ovid, were perfectly at home in literary circles.[46] When she could find the time, Catherine occasionally wrote verses herself, which she would show to the court poets.[47] Her reading was not entirely highbrow, however. A superstitious woman, she believed implicitly in astrology and soothsaying, and her reading matter included The Book of Sibyls and the almanacs of Nostradamus.[48]

Catherine patronised poets such as Pierre de Ronsard, Rémy Belleau, Jean-Antoine de Baïf, and Jean Dorat, who wrote verses, scripts, and associated literature for her court festivals, and for public events such as royal entries and royal weddings.[49] Catherine even had Ronsard write a poem to Elizabeth of England, honouring a new peace treaty.[50] These poets were part of a group sometimes known as the Pléiade, who forged a vernacular French literature on Greek and Latin models. They gave form to their interest in ancient poetry in vers mesurés, a metric system that aspired to imitate classical poetic rhythms. Catherine de' Medici was also interested in Italian literature: Tasso presented his Rinaldo to her, and Aretino eulogised her as "woman and goddess serene and pure, the majesty of beings human and divine".[51]

Theatre

In 1559, Catherine and Henry II attended a performance of the tragedy Sophonisba by Trissino, adapted earlier by the poet Mellin de Saint-Gelais to Catherine's commission.[52] The performance style of the day inserted musical interludes unrelated to the plot between the acts, devoted to praise of the royal court. Princesses and other high-ranking ladies performed on this occasion, which celebrated royal and noble marriages.[51] Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de Brantôme, claimed in his memoirs that having seen Sophonisba shortly before her husband's death, Catherine refused to watch any more tragedies, believing the play had brought him bad luck. Tragedy went out of fashion at the court soon afterwards, replaced by the new genre of tragicomedy, though the change in taste may have had less directly to do with Catherine than with the revulsion of the court against the violence of the times.[51] Genevra, staged at Fontainebleau on 13 February 1564, adapted into French from an episode of Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, was the first tragicomedy known to have been performed for the French court.[51]

Catherine enjoyed comedy and risqué humour. She drew the line at obscenity, however: in 1567, after seeing Le Brave, an adaptation of Plautus's Miles Gloriosus by one of her official poets Jean-Antoine de Baïf, Catherine told the author to cut the "lascivious talk" of the classical writers.[53] In the 1570s, the Italian commedia dell'arte rose to popularity in France and became all the rage.[54] Catherine was not, as has sometimes been supposed, the first to bring Italian comedy to France: Louis Gonzaga, Duke of Nevers, himself an Italian, was the first to invite high-quality Italian players to France in 1571. The following year, two companies called I Gelosi appeared in Paris, and a performance was given to the court in Blois. A year later, I Gelosi performed during the celebrations for the marriage of Catherine's daughter Marguerite de Valois and Henry of Navarre. Further groups appeared under the same name in the reign of Catherine's son Henry III (1574–89).

Court festivals

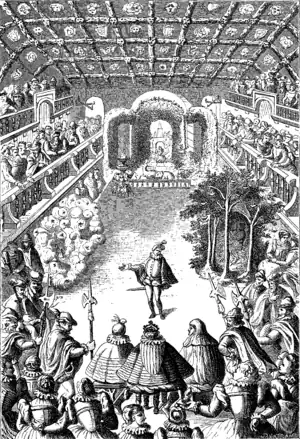

As queen consort of France, Catherine patronised the arts and the theatre, but not until she attained real political and financial power as queen mother did she begin the series of tournaments and entertainments, sometimes called "magnificences", that dazzled her contemporaries and continue to fascinate scholars. The most famous of these were the court festivals mounted at Fontainebleau and at Bayonne during Charles IX's royal progress of 1564–65; the entertainments for the Polish ambassadors at the Tuileries in 1573; and the celebrations following the marriages of Catherine's daughter Marguerite to Henry of Navarre in 1572 and of her daughter-in-law's sister, Marguerite of Lorraine, to Anne, Duke of Joyeuse, in 1581. On all these occasions, Catherine organised sequences of lavish and spectacular entertainments. Biographer Leonie Frieda suggests that "Catherine, more than anyone, inaugurated the fantastic entertainments for which later French monarchs also became renowned".[55]

For Catherine, these entertainments were worth their colossal expense, since they served a political purpose. Presiding over the royal government at a time when the French monarchy was in steep decline, she set out to show not only the French people but foreign courts that the Valois monarchy was as prestigious and magnificent as it had been during the reigns of Francis I and her husband Henry II.[56] At the same time, she believed these elaborate entertainments and sumptuous court rituals, which incorporated martial sports and tournaments of many kinds, would occupy her feuding nobles and distract them from fighting against each other to the detriment of the country and the royal authority.[57]

It is clear, however, that Catherine regarded these festivals as more than a political and pragmatic exercise; she revelled in them as a vehicle for her creative gifts. A highly talented and artistic woman, Catherine took the lead in devising and planning her own musical-mythological shows and is regarded as their creator as well as their sponsor. Historian Frances Yates has called her "a great creative artist in festivals".[58] Though they were ephemeral, Catherine's "magnificences" are studied by modern scholars as works of art.[55] Catherine employed the leading writers, artists, and architects of the day, including Antoine Caron, Germain Pilon, and Pierre Ronsard, to create the dramas, music, scenic effects, and decorative works required to animate the themes of the festivals, which were usually mythological and dedicated to the ideal of peace in the realm. It is difficult for scholars to reconstruct the exact form of Catherine's entertainments, but research into the written accounts, scripts, artworks, and tapestries that derived from these famous occasions has provided evidence of their richness and scale.

In the tradition of 16th-century royal festivals, Catherine de' Medici's magnificences took place over several days, with a different entertainment on each day. Often individual lords and ladies and members of the royal family were responsible for preparing one particular entertainment. Spectators and participants, including those involved in martial sports, would dress up in costumes representing mythological or romantic themes. Catherine gradually introduced changes to the traditional form of these entertainments. She forbade heavy tilting of the sort that led to the death of her husband in 1559; and she developed and increased the prominence of dance in the shows that climaxed each series of entertainments.

Dance

A distinctive new art form, the ballet de cour, emerged from the creative advances in court entertainment devised by Catherine de' Medici.[59] The Italian influence on the ballet de cour owed much to Catherine, who was Italian herself and had grown up in Florence, where intermedii, patronised by her rich relatives, were a staple of court entertainments and a focus of innovation. These between-acts entertainments had evolved a unique artistic form of their own, with choral dances, masquerades (mascherate), and consecutive themes.[60] Once in France, Catherine kept in touch with artistic innovations in Italy. She encouraged Italian dancing masters to accept posts in France, among them the Milanese Cesare Negri, who introduced the skills of figured dancing to France, and Pompeo Diobono, whom Catherine employed as dancing master to her four sons.[61] The most significant figure was Balthasar de Beaujoyeulx (his name gallicised from the Italian Baldassare da Belgiojoso), whom Catherine placed in charge of training dancers and producing performances at court.[62]

Historian Frances Yates has credited Catherine as the guiding light of the ballets de cour:

It was invented in the context of the chivalrous pastimes of the court, by an Italian, and a Medici, the Queen Mother. Many poets, artists, musicians, choreographers, contributed to the result, but it was she who was the inventor, one might perhaps say, the producer; she who had the ladies of her court trained to perform these ballets in settings of her devising.[58]

The dance performances at the Valois court were conceived on a large scale, as elaborate, choreographed showpieces, sometimes performed by considerable forces. At the Château of Fontainebleau in 1564, the court attended a ball in which 300 "beauties dressed in gold and silver cloth" performed a choreographed dance.[63] In his illustrated Magnificentissimi spectaculi, Jean Dorat described an intricate ballet, The Ballet of the Provinces of France, performed for the Polish ambassadors at the Tuileries palace in 1573, in which sixteen nymphs, each representing a French province, distributed devices to the spectators as they danced. Choreographed by Beaujoyeulx, the dancers performed complex, interlaced figures and patterned movements, each expressing a certain moral or spiritual truth that the spectators, assisted by printed programmes, were expected to recognise.[64] The chronicler Agrippa d'Aubigné recorded that the Poles marvelled at the ballet.[65] Brantôme called the performance "the finest ballet that was ever given in this world" and praised Catherine for bringing prestige to France with "all these inventions".[65] Jean Dorat described the movements of the dancers in verse:

- They blend a thousand flights with a thousand pauses of the feet

- Now they stitch through one another like bees by holding hands

- Now they form a point like a flock of voiceless cranes.

- Now they draw close, intertwining with one another

- Creating an entangled hedge like a kind of bramble bush.

- Now this one and now that switches to a flat figure

- Which describes many letters without a tablet.[66]

After the dance was over, Catherine invited the spectators to join with the performers in a social dance.

Over the years, Catherine increased the element of dance in her festive entertainments, and it became the norm for a major ballet to climax each series of magnificences. The Ballet Comique de la Reine, devised under Catherine's influence, by Queen Louise for the Joyeuse Magnificences of 1581, is regarded by historians as the moment when the ballet de cour assumed the character of a new art form. The theme of the entertainment was an invocation of cosmic forces to aid the monarchy, which at that time was threatened by the rebellion not only of Huguenots but of many Catholic nobles. Men were shown as reduced to beasts by Circe, who held court in a garden at one end of the hall. Louise and her ladies, costumed as naiads, entered on a chariot designed as a fountain and then danced a ballet of thirteen geometric figures. After being turned to stone by Circe, they were freed to dance a ballet of forty geometric figures. Four groups of dancers, each wearing a different-coloured costume, moved through a sequence of patterns, including squares, triangles, circles, and spirals.[67]

The figured choreography that enacted the mythological and symbolic themes reflected the principle, derived from the Enneads of Plotinus (c. 205–270), of "cosmic dance", the imitation of heavenly bodies by human motion to produce harmony. This imitation was achieved in the dance through geometric choreography and figures based on the harmony of numbers.[68] The dance elements in the court festivities represented a response to the increasing political disharmony of the country.[64] The Ballet Comique de la Reine marked the final transformation of court dance as a purely personal and social activity into a unified theatrical performance with a philosophical and political agenda.[69] Owing to its synthesis of dance, music, verse, and setting, the production is regarded by scholars as the first authentic ballet.[70]

Music

The dance, verse, and musical elements of Catherine's entertainments increasingly reflected the principles of an academic movement—also influential in the Florentine Camerata—to unify the performing arts in what was believed to be the classical, Greek way. In 1570, Jean-Antoine de Baïf founded the Académie de Poésie et de Musique, whose aim was to revive ancient metrical practices, and, though the academy was short lived, similar aims were adopted by the Académie du Palais, founded in 1577. Both enterprises were supported by the Valois court. One result of this movement was Musique mesurée à l'antique, in which the metres of music and verse were matched precisely, to create a new harmony. The theory was not merely technical but humanistic; practitioners believed a harmonious combination of elements would produce benign moral and ethical effects on the audience. Dance was also subject to the new system and was designed to match the rhythms of the music and verse. The result was a new unified approach to the interrelationship between the performing arts.[71]

The well-documented Joyeuse magnificences of 1581 provide the clearest evidence of the influence of this artistic movement on Catherine de' Medici's entertainments. The chief composer of music for the performances was Claude Le Jeune (1528–1600). His musique mesurée was played at the wedding itself, and his song "La Guerre" was sung during a foot-combat in the Louvre. He also wrote the music for an elaborate show on a sun-moon theme, once again setting vers mesurés to musique mesurée.[72] For the Ballet Comique de la Reine, the music was composed by the Sieur de Beaulieu. The musicians were fully incorporated in the dramatic whole: on one side of the performing space was a cloud containing costumed singers and musicians, and on the other, a grotto, guarded by Pan, containing a second band of musicians. Further groups of singers and musicians made various entries and exits during the five-and-a-half-hour performance. At one stage, Circe turned the dancers and musicians to stone.[73] When, at the climax of the show, Jupiter descended from the heavens, forty singers and musicians performed a song in honour of the wisdom and virtue of the Valois monarchy.[74] Published accounts praised the length and variety of the music. The Jupiter music was called the "most learned and excellent music that had ever been sung or heard".[75]

Notes

- 1 2 Knecht, 244.

- ↑ Knecht, 220.

- 1 2 Zvereva, 6.

- ↑ Knecht, 245.

- ↑ Knecht, 240–41.

- ↑ Frieda, 109.

- ↑ Dimier, 195. The similarity in sizes suggests that they were ordered to her specifications.

- ↑ Jollet, 50: Correspondance Diplomatique De Bertrand De Salignac De La Mothe Fenelon, vol. 6, (1840), 229-231, 3 July 1571

- ↑ See Zvereva, Les Clouet de Catherine de Médicis, 2002.

- ↑ Blunt, 73.

- ↑ Dimier, 239.

- ↑ Dimier, 205–6.

- ↑ Blunt, 100; Jollet, 249–52.

- ↑ Dimier, 308–19; Jollet, 17–18. Technically, François Clouet's origins were Flemish, since his father had arrived in Paris from Flanders prior to 1528; but François lived almost all of his life in France

- ↑ "There are few periods at which French painting was at a lower ebb than in the last quarter of the sixteenth century and the first quarter of the seventeenth, and few periods about which we are more ignorant." Blunt, 98.

- ↑ Blunt calls Caron's style "perhaps the purest known type of Mannerism in its elegant form, appropriate to an exquisite but neurotic society". Blunt, 98, 100.

- 1 2 3 Blunt, 100.

- ↑ Blunt, 98.

- 1 2 Knecht, 242–43.

- ↑ Dimier, 190. Caron was also responsible for a series of cartoons for tapestries on the theme of Artemisia, in honour of Catherine de' Medici.

- ↑ See The Valois Tapestries (1959), by Frances Yates, who proposed de Heere as the designer of the additions.

- ↑ Dimier, 216. The information about de Heere comes from Karel van Mander (1548–1606).

- 1 2 Knecht, 242.

- ↑ Blunt, 282; Knecht, 225. Da Volterra died in 1566. The horse did not reach France until the seventeenth century, when it was utilised for an equestrian statue of Louis XIII. It was melted down during the French revolution.

- 1 2 Blunt, 94.

- ↑ Hoogvliet, 110.

- ↑ Hoogvliet, 111. Ronsard may refer to Artemisia, who drank the ashes of her dead husband, which fused with her own body.

- ↑ Knecht, 225, quotes Henri Zerner, L’art de la Renaissance en France. L'invention du classicisme, Paris: Flammarion, 1996, 354. The urn is a nineteenth-century restoration.

- ↑ Zerner, 383. Whereas the Resurrection for the tomb of Francis I had been positioned close to the corpses, this design would have involved the visitor.

- ↑ Blunt, 95. Pilon based the Christ on Michelangelo's cartoon for Noli me tangere (1531) and carved the soldiers in Michelangelo's contrapposto style.

- ↑ Blunt, 96–97.

- ↑ Babelon, 263.

- ↑ Frieda, 79, 455; Sutherland, Ancien Régime, 6.

- ↑ De l'Orme wrote that Catherine, with "an admirable understanding combined with great prudence and wisdom", took the trouble "to order the organization of her said palace [the Tuileries] as to the apartments and location of the halls, antechambers, chambers, closets and galleries, and to give the measurements of width and length". Quoted by Knecht, 228.

- ↑ Blunt, 91. For example, Jacques Androuet du Cerceau dedicated his Les Plus Excellents Bastiments de France (1576 and 1579) to Catherine.

- ↑ Knecht, 228.

- ↑ Knecht, 227. Henry's gesture is now unclear, since a missal, resting on a prie-dieu (prayer desk), was removed from the sculpture during the French revolution and melted down.

- 1 2 Knecht, 223.

- ↑ Frieda, 266; Hoogvliet, 108. Louis Le Roy, in his Ad illustrissimam reginam D. Catherinam Medicem of 1560, was the first to call Catherine the "new Artemisia".

- ↑ Blunt, 56.

- ↑ L’art de la Renaissance en France. L'invention du classicisme (Zerner, 1996: 349–54), quoted by Knecht, 227; Zerner, 379.

- ↑ Knecht, 269.

- ↑ Thomson, 168.

- ↑ Quoted in Knecht, 233. Ronsard addressed these lines to the financial official Raoul Moreau. Au tresorier de l'esparne (ca. 1573).

- ↑ Hoogvliet, 109.

- ↑ Sutherland, Secretaries of State, 153–56.

- ↑ Heritier, 460.

- ↑ Knecht, 221, 244–45

- ↑ Frieda, 105.

- ↑ Heritier, 238–39.

- 1 2 3 4 Knecht, 234.

- ↑ Plazenet, 261.

- ↑ Knecht, 235.

- ↑ Heller, 104.

- 1 2 Frieda, 225.

- ↑ Strong, 99.

- ↑ Yates, 51–52.

• Catherine wrote to Charles IX: "I heard it said to your grandfather the King that two things were necessary to live in peace with the French and have them love their King: keep them happy, and busy at some exercise, notably tournaments; for the French are accustomed, if there is no war, to exercise themselves and if they are not made to do so they employ themselves to more dangerous [ends]". Quoted in Jollet, 111. - 1 2 Yates, 68.

- ↑ Yates, 51; Strong, 102, 121–22.

- ↑ Shearman, 105.

- ↑ Lee, 39.

- ↑ Lee, 40–42.

- ↑ Frieda, 211.

- 1 2 Lee, 42.

- 1 2 Knecht, 239.

- ↑ Quoted in Lee, 43.

- ↑ Lee, 45; Strong, 120–21.

- ↑ Lee, 41–42.

- ↑ Lee, 41. See also Orchésographie (1588) by Thoinot Arbeau, the first publication to notate—in relation to music—the steps taken from social dances.

- ↑ Lee, 44.

- ↑ Strong, 102.

- ↑ Strong, 118.

- ↑ Strong, 119–20.

- ↑ Strong, 121.

- ↑ Knecht, 241.

Bibliography

- Babelon, Jean-Pierre. "The Louvre: Royal Residence and Temple of the Arts". Realms of Memory: The Construction of the French Past. Vol. III: Symbols. Edited by Pierre Nora. English language edition translated by Arthur Goldhammer, edited by Lawrence D. Kritzman. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-231-10926-1.

- Blunt, Anthony. Art and Architecture in France: 1500–1700. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, [1957] 1999 edition. ISBN 0-300-07748-3.

- Brantôme, Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de. Illustrious Dames of the Court of the Valois Kings. Translated by Katharine Prescott Wormeley. New York: Lamb, 1912. OCLC 347527.

- Chastel, André. French Art: The Renaissance, 1430–1620. Translated by Deke Dusinberre. Paris: Flammarion, 1995. ISBN 2-08-013583-X.

- Cloulas, Ivan, and Michelle Bimbenet-Privat. Treasures of the French Renaissance. Translated by John Goodman. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998. ISBN 0-8109-3883-9.

- Dimier, L. French Painting in the XVI Century. Translated by Harold Child. London: Duckworth, 1904. OCLC 86065266.

- Frieda, Leonie. Catherine de Medici. London: Phoenix, 2005. ISBN 0-75-382039-0.

- Heller, Henry. Anti-Italianism in Sixteenth-Century France. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8020-3689-9.

- Heritier, Jean. Catherine de' Medici. Translated by Charlotte Haldane. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1963. OCLC 1678642.

- Hoogvliet, Margriet. "Princely Culture and Catherine de Médicis". In Princes and Princely Culture, 1450-1650. Edited by Gosman, Martin; Alasdair A. MacDonald, and Arie Johan Vanderjagt. Leiden and Boston, Massachusetts: Brill Academic, 2003. ISBN 90-04-13572-3.

- Jardine, Lisa, and Jerry Brotton. Global Interests: Renaissance Art Between East And West. London: Reaktion Books, 2005. ISBN 1-86189-166-0.

- Jollet, Etienne. Jean et François Clouet. Translated by Deke Dusinberre. Paris: Lagune, 1997. ISBN 0-500-97465-9.

- Knecht, R. J. Catherine de' Medici. London and New York: Longman, 1998. ISBN 0-582-08241-2.

- Lee, Carol. Ballet in Western Culture: A History of Its Origins and Evolution. London: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0-415-94256-X.

- McGowan, Margaret. Dance in the Renaissance: European Fashion, French Obsession. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-300-11557-1.

- Plazenet, Laurence. "Jacques Amyot and the Greek Novel". In The Classical Heritage in France. Edited by Gerald Sandy. Leiden and Boston, Massachusetts: Brill Academic, 2002. ISBN 90-04-11916-7.

- Shearman, John. Mannerism. London: Penguin, 1967. ISBN 0-14-020808-9.

- Strong, Roy. Art and Power: Renaissance Festivals, 1450–1650. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 1984. ISBN 0-85115-247-3.

- Sutherland, N. M. Catherine de Medici and the Ancien Régime. London: Historical Association, 1966. OCLC 1018933.

- Sutherland, N. M. The French Secretaries of State in the Age of Catherine de Medici. London: Athlone Press, 1962. OCLC 1367811.

- Thomson, David. Renaissance Paris: Architecture and Growth, 1475-1600. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984 (retrieved 21 March 2008). ISBN 0-520-05347-8.

- Treadwell, Nina. Music and Wonder at the Medici Court: The 1589 Interludes for La pellegrina. Indiana University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-253-35218-5.

- Yates, Frances. The Valois Tapestries. 1959. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1999. ISBN 0-415-22043-2.

- Zerner, Henri. Renaissance Art in France. The Invention of Classicism. Translated by Deke Dusinberre, Scott Wilson, and Rachel Zerner. Paris: Flammarion, 2003. ISBN 2-08-011144-2.

- (in French) Zvereva, Alexandra. Les Clouet de Catherine de Médicis. Paris: Somogy, Éditions d'Art; Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly, 2002. ISBN 2-85056-570-9.