| Binucleated cells | |

|---|---|

| |

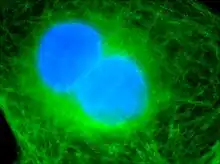

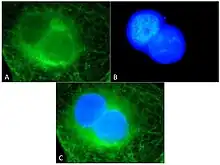

| A binucleated cell has two nuclei. The cell above was stained with DAPI to highlight the nuclei and treated with antibodies against tubulin to highlight the microtubules to show the binucleation. | |

| Specialty | Pathology |

Binucleated cells are cells that contain two nuclei. This type of cell is most commonly found in cancer cells and may arise from a variety of causes. Binucleation can be easily visualized through staining and microscopy. In general, binucleation has negative effects on cell viability and subsequent mitosis.

They also occur physiologically in hepatocytes, chondrocytes and in fungi (dikaryon).

Causes

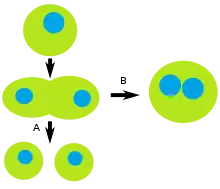

- Cleavage furrow regression: Cells divide and almost complete division but then the cleavage furrow begins to regress and the cells merge. This is thought to be caused by nondisjunction in chromosomes but the mechanism by which it occurs is not well understood.[1]

- Failed cytokinesis: The cell can fail to form a cleavage furrow, leading to both nuclei remaining in one cell.[1]

- Multipolar spindles: Cells contain three or more centrioles, resulting in multiple poles. This leads to the cells pulling chromosomes in many directions that end in multiple nuclei found in one cell.[1]

- Merging of newly formed cells: Two cells that have just finished cytokinesis merge into one another. This process is not entirely understood.[1]

Medical relevance

Detection

Binucleated cells can be observed using microscopy. Cells must first be fixed to arrest them wherever they are in the cell cycle and to keep their structures from degrading. Their nuclei and tubulin must next be made visible so that binucleation can be identified. DAPI is a dye that binds to DNA and fluoresces blue. For this reason, it is particularly useful at labeling nuclei. Antibody probes can be used to label tubulin fluorescently. The immunofluorescence may then be observed with microscopy. Binucleated cells are most easily identified by viewing tubulin, which surrounds the two nuclei in the cell. Binucleated cells may be mistaken for two cells in close proximity when viewing only nuclei.

Cancer

Binucleation occurs at a much higher rate in cancer cells.[1] Other identifying features of cancer cells include multipolar spindles, micronuclei, and chromatin bridge. However, the increased rate of binucleation is usually not high enough to make it a conclusive diagnostic tool.

Effects

The fate of binucleated cells depends largely on the type of cell they originated from.[1] A large percentage of binucleated cells arising from normal cells remain in interphase and never enter mitosis again.[1] Cells that contain many mutations before they become binucleate are much more likely to proceed through subsequent rounds of mitosis.[1] One study found that more than 50% of binucleated cells never entered mitosis again while greater than 95% of cancer cells were able to proceed through mitosis.[1] Subsequent rounds of mitosis in binucleated cells have much higher rates of errors in chromosomal disjunction making it much more likely for cells to accumulate mutations.[1]