| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

The Bhagavata tradition, also called Bhagavatism, refers to an ancient religious sect that traced its origin to the region of Mathura.[5] After its syncretism with the Brahmanical tradition of Vishnu, Bhagavatism became a pan-Indian tradition by the second century BCE, according to R.C. Majumdar.[6]

Historically, Bhagavatism corresponds to the development of a popular theistic movement in India, departing from the elitist sacrificial rites of Vedism,[7] and initially focusing on the worship of the Vrishni hero Vāsudeva in the region of Mathura.[1] It later assimilated into the concept of Narayana[8] where Krishna is conceived as svayam bhagavan. According to some historical scholars, worship of Krishna emerged in the 1st century BCE. However, Vaishnava traditionalists place it in the 4th century BCE.[9] Despite relative silence of the earlier Vedic sources, the features of Bhagavatism and principles of monotheism of Bhagavata school unfolding described in the Bhagavad Gita as viewed as an example of the belief that Vāsudeva-Krishna is not an avatar of the Vedic Vishnu, but is the Supreme.[10][11]

Definition of Krishnaism

In the ninth century CE Bhagavatism was already at least a millennium old and many disparate groups, all following the Bhagavata Purana could be found. Various lineages of Gopala worshipers developed into identifiable denominations. However, the unity that exists among these groups in belief and practice has given rise to the general term Krishnaism. Today the faith has a significant following outside of India as well.[13] Many places associated with Krishna such as Vrindavan attract millions of pilgrims each year who participate in religious festivals that recreate scenes from Krishna's life on Earth. Some believe that early Bhagavatism was enriched and transformed with powerful and popular Krishna tradition with a strong "human" element to it.[14]

Initial History of Bhagavata tradition

It is believed that Bhagavatas borrowed or shared the attribute or title Purusa of their monotheistic deity from the philosophy of Sankhya. The philosophy was formulated by the end of the 4th century BCE and as time went other names such as Narayana were applied to the main deity of Krishna-Vāsudeva.[15]

Second early stage

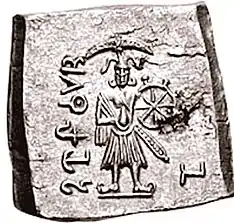

The association of the Sun-bird Garuda with the "Devadeva" ("God of Gods") Vāsudeva in the Heliodorus pillar (113 BCE) suggests that the Bhagavat cult of human deities had already absorbed the Sun-god Vishnu, an ancient Vedic deity.[16] Slightly later, the Nagari inscription also shows the incorporation of the Brahmanical deity Narayana into the hero-cult of Bhagavatism.[16] Vishnu would much later become prominent in this construct, so that by the middle of the 5th century CE, during the Gupta period, the term Vaishnava would replace the term Bhagavata to describe the followers of this cult, and Vishnu would now be more popular than Vāsudeva.[16] Bhagavatism would introduce the concept of the chatur-vyuhas, in which the four earthly emanations of Narayana were considered to be Vasudeva (Krishna) as the creator, Sankarsana (Balarama) as the preserver, Pradyumna as the destroyer, and Aniruddha as the aspect of intellect. The concept of vyuhas would later be supplanted by the concept of avataras, indicating the transformation of Bhagavatism into Vaishnavism.[17]

Some relate absorption by Brahmanism to be the characteristic of the second stage of the development of the Bhagavata tradition. It is believed that at this stage Krishna-Vāsudeva was identified with the deity of Vishnu, that according to some belonged to the pantheon of Brahmanism.[18]

Rulers onwards from Chandragupta II, Vikramaditya were known as parama Bhagavatas, or Bhagavata Vaishnavas. The Bhagavata Purana entails the fully developed tenets and philosophy of the Bhagavata cult where Krishna gets fused with Vasudeva and transcends Vedic Vishnu and cosmic Hari to be turned into the ultimate object of bhakti.[19]

Adoption in Tamilakam

With the fall of the Guptas, Bhagavatism had lost its pre-eminence in the north, with Vardhana sovereigns such as Harsha adhering to non-Bhagavata creeds.[20] Though the Bhagavata religion still flourished in the north, its stronghold was now not the valley of the Ganges or Central India, but the Tamil country. There, the faith flourished under the strong impetus given by the Alvars, "who by their Tamil songs inculcated Bhakti and Krishna-worship mainly". Bhagavatism had penetrated into the Deccan at least as early as the first century BCE. The Silappadikaram and the other ancient Tamil poems refer to temples dedicated to Krishna and his brother at Madura, Kaviripaddinam, and other cities. The wide prevalence of Bhagavatism in the far south is also testified to by the Bhagavata Purana which says that in the Kali Age, devoted worshippers of Narayana, though rare in some places, are to be found in large numbers in the Dravida country watered by the rivers Tamraparnl, Kritamala, the sacred Kaveri, and the great stream (Periyar) flowing to the west.[21] Yamunacharya, who laid the tenets of the Vishishtadvaita philosophy, has his works described as "a somewhat modified and methodical form of the ancient Bhagavata, Pancharatra, or Satvata religion".[22] The Alvars would be among the first catalysts of the Bhakti movement, a Hindu revivalist movement that would reintroduce Bhagavata philosophy back to its place of origin.[23]

Literary references

References to Vāsudeva also occur in early Sanskrit literature. Taittiriya Aranyaka (X, i,6) identifies him with Narayana and Vishnu. Pāṇini, ca. 4th century BCE, in his Ashtadhyayi explains the word "Vāsudevaka" as a Bhakta (devotee) of Vāsudeva. At some stage during the Vedic period, Vāsudeva and Krishna became one deity or three distinct deities Vāsudeva-Krishna, Krishna-Gopala and Narayana, all become identified with Vishnu,[24] and by the time of composition of the redaction of Mahabharata that survives till today.

A Gupta period research makes a "clear mention of Vāsudeva as the exclusive object of worship of a group of people", who are referred to as Bhagavatas.[25]

According to an opinion of some scholars, in Patanjali's time identification of Krishna with Vāsudeva is an established fact as is surmised from a passage of the Mahabhasya – (jaghana kamsam kila vasudevah).[26] This "supposed earliest phase is thought to have been established from the sixth to the fifth centuries BCE at the time of Pāṇini, who in his Astadhyayi explained the word vāsudevaka as a bhakta, devotee, of Vāsudeva and it is believed that Bhagavata religion with the worship od Vāsudeva Krishna was at the root of the Vaishnavism in Indian history."[27][28]

Other meanings

In the recent times, this often refer to a particular sect of Vaishnavas in West India, referring to themselves as 'Bhagavata-sampradaya'.[29][30]

It is also a common greeting among the followers of Ramanujacharya and other yoga sects.

See also

References

- 1 2 "A cult of Vāsudeva, known as Bhagavatism, was already in existence by the second century BC." in Srinivasan, Doris (1981). Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-06498-0.

- ↑ Subburaj, V.V.K. (2004). Basic Facts of General Knowledge. Sura Books. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-81-7254-234-4.

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 437. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- ↑ Joshi, Nilakanth Purushottam (1979). Iconography of Balarāma. Abhinav Publications. p. 22. ISBN 978-81-7017-107-2.

- ↑ Patel, Sushil Kumar (1992). Hinduism in India: A Study of Viṣṇu Worship. Amar Prakashan. p. 18. ISBN 978-81-85420-35-6.

- ↑ Majumdar, R. C. (1 January 2016). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 172. ISBN 978-81-208-0435-7.

- ↑ Sastri, K. a Nilakanta (1952). Age of the Nandas And Mauryas. pp. 304–305.

- ↑ Beck, G. (2005). "Krishna as Loving Husband of God". Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity. ISBN 978-0-7914-6415-1. Retrieved 28 April 2008. Vishnu was by then assimilated with Narayana

- ↑ Hastings 2003, pp. 540–42

- ↑ Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many heads, arms, and eyes: origin, meaning, and form of multiplicity in Indian art. Leiden: Brill. p. 134. ISBN 90-04-10758-4.

- ↑ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 76.

- ↑ Osmund Bopearachchi, 2016, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence

- ↑ Schweig, Graham M. (2005). Dance of Divine Love: The Rڄasa Lڄilڄa of Krishna from the Bhڄagavata Purڄa. na, India's classic sacred love story. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. Front Matter. ISBN 0-691-11446-3.

- ↑ KLOSTERMAIER, Klaus K. (2007). A Survey of Hinduism. State University of New York Press; 3 edition. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-7914-7081-7.

Not only was Krsnaism influenced by the identification of Krsna with Vishnu, but also Vaishnavism as a whole was partly transformed and reinvented in the light of the popular and powerful Krishna religion. Bhagavatism may have brought an element of cosmic religion into Krishna worship; Krishna has certainly brought a strongly human element into Bhagavatism. ... The center of Krishna-worship has been for a long time Brajbhumi, the district of Mathura that embraces also Vrindavana, Govardhana, and Gokula, associated with Krishna from the time immemorial. Many millions of Krishna bhaktas visit these places ever year and participate in the numerous festivals that reenact scenes from Krshnas life on Earth

- ↑ Hastings 2003, p. 540

- 1 2 3 Indian History. Allied Publishers. 1988. p. A-224. ISBN 978-81-8424-568-4.

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (1975). Materials for the Study of the Early History of the Vaishnava Sect. Oriental Books Reprint Corporation. pp. 175–176.

- ↑ Hastings 2003, p. 541, Bhakti Marga

- ↑ Kalyan Kumar Ganguli (1988). Sraddh njali, Studies in Ancient Indian History: D.C. Sircar Commemoration: Puranic tradition of Krishna. Sundeep Prakashan. ISBN 81-85067-10-4.p.36

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (1936). Early History of the Vaishnava Sect Ed. 2nd. p. 178.

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (1936). Early History of the Vaishnava Sect Ed. 2nd. p. 181.

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (1936). Early History of the Vaishnava Sect Ed. 2nd. pp. 191–192.

- ↑ Pillai, P. Govinda (4 October 2022). The Bhakti Movement: Renaissance or Revivalism?. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-78039-0.

- ↑ Flood, Gavin D. (1996). An introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 341. ISBN 0-521-43878-0. Retrieved 21 April 2008."Early Vaishnava worship focuses on three deities who become fused together, namely Vāsudeva-Krishna, Krishna-Gopala and Narayana, who in turn all become identified with Vishnu. Put simply, Vāsudeva-Krishna and Krishna-Gopala were worshiped by groups generally referred to as Bhagavatas, while Narayana was worshipped by the Pancaratra sect"

- ↑ Banerjea, 1966, page 20

- ↑ A Corpus of Indian Studies: Essays in Honour of Professor Gaurinath Sastri, Page 150, 1980 – 416 pages.

- ↑ Page 76 of 386 pages: The Bhagavata religion with the worship of Vasudeva Krishna as the ... of Vasudeva Krishna and they are the direct forerunners of Vaisnavism in India.Ehrenfels, U.R. (1953). "The University of Gauhati". Dr. B. Kakati Commemoration Volume.

- ↑ Page 98: In the Mahabharata, Vasudeva-Krishna is identified with the highest God.Mishra, Y.K. (1977). Socio-economic and Political History of Eastern India. Distributed by DK Publishers' Distributors.

- ↑ General, A. (1920). "I. The Bhagavata Sampradaya". An Outline of the Religious Literature of India.

- ↑ Singhal, G.D. (1978). "The Cultural Evolution of Hindu Gaya, the Vishnu Dham". The Heritage of India: LN Mishra Commemoration Volume.

- ↑ "The Newly Discovered Three Sets of Svetaka Gangacopper Plates" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Kielhorn, F. (1908). "Bhagavats, Tatrabhavat, and Devanampriya". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society: 502–505. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

Further reading

- Dahmen-Dallapiccola, Anna Libera; Dallapiccola, Anna L. (2002). Dictionary of Hindu lore and legend. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-51088-1.

- Hastings, James Rodney (2003) [1908–26]. Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Vol. 4 of 24 ( Behistun (continued) to Bunyan.). John A Selbie (2nd edition 1925–1940, reprint 1955 ed.). Edinburgh: Kessinger Publishing, LLC. p. 476. ISBN 0-7661-3673-6. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

The encyclopaedia will contain articles on all the religions of the world and on all the great systems of ethics. It will aim at containing articles on every religious belief or custom, and on every ethical movement, every philosophical idea, every moral practice.

- Thompson, Richard, PhD (December 1994). "Reflections on the Relation Between Religion and Modern Rationalism". Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gupta, Ravi M. (2004). Caitanya Vaisnava Vedanta: Acintyabhedabheda in Jiva Gosvami's Catursutri tika. University of Oxford.

- Gupta, Ravi M. (2007). Caitanya Vaisnava Vedanta of Jiva Gosvami. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-40548-5.

- Ganguli, K.M. (1883–1896). The Mahabharata of Krishna Dwaipayana Vyasa. Kessinger Publishing.

- Ganguli, K.M. (1896). Bhagavad-gita (Chapter V). The Mahabharata, Book 6. Calcutta: Bharata Press.

- Wilson, H.H. (1840). The Vishnu Purana, a System of Hindu Mythology and Tradition: Translated from the Original Sanscrit and Illustrated by Notes Derived Chiefly from Other Puranas. Printed for the Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland.

- Prabhupada, A.C. (1988). Srimad Bhagavatam. Bhaktivedanta Book Trust.

- Kaviraja, K.; Prabhupada, A.C.B.S.; Bhaktivedanta, A.C. (1974). Sri Caitanya-Caritamrta of Krsnadasa Kaviraja. Imprint unknown.

- Goswami, S.D. (1998). The Qualities of Sri Krsna. GNPress. pp. 152 pages. ISBN 0-911233-64-4.

- Garuda Pillar of Besnagar, Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report (1908–1909). Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1912, 129.

- Rowland, B. Jr. (1935). "Notes on Ionic Architecture in the East". American Journal of Archaeology. 39 (4): 489–496. doi:10.2307/498156. JSTOR 498156. S2CID 193092935.

- Delmonico, N. (2004). "The History of Indic Monotheism And Modern Chaitanya Vaishnavism". The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant. ISBN 978-0-231-12256-6. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- Mahony, W.K. (1987). "Perspectives on Krsna's Various Personalities". History of Religions. 26 (3): 333–335. doi:10.1086/463085. JSTOR 1062381. S2CID 164194548.

- Beck, Guy L., ed. (2005). Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-6415-6.

- Vyasanakere, Prabhanjanacharya. Download and Listen to Bhagavata in Kannada. Vyasamadhwa Samshodhana Pratishtana. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Vyasanakere, Prabhanjanacharya. Download and Listen Shloka by Shloka of Bhagavata and translation in Kannada. Vyasamadhwa Samshodhana Pratishtana. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2016.