| Bernard-Soulier syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hemorrhagiparous thrombocytic dystrophy[1] |

| |

| Bernard-Soulier syndrome has an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance (rarely autosomal dominant).[2] | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Causes | Mutations in GP1BA, GP1BB and GP9[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Flow cytometry analysis[1] |

| Treatment | Platelet transfusion[4] |

Bernard–Soulier syndrome (BSS) is a rare autosomal recessive bleeding disorder that is caused by a deficiency of the glycoprotein Ib-IX-V complex (GPIb-IX-V), the receptor for von Willebrand factor.[5] The incidence of BSS is estimated to be less than 1 case per million persons, based on cases reported from Europe, North America, and Japan. BSS is a giant platelet disorder, meaning that it is characterized by abnormally large platelets.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Bernard–Soulier syndrome often presents as a bleeding disorder with symptoms of:[7]

- Perioperative (and postoperative) bleeding

- Bleeding gums

- Bruising

- Epistaxis (nosebleeds)

- Abnormal bleeding (from small injuries)

- Unusual menstrual periods

Genetics

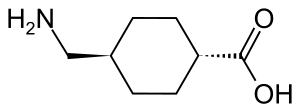

In regards to mechanism, there are three genes: GP1BA, GP1BB and GP9 that are involved (due to mutations).[3] These mutations do not allow the GPIb-IX-V complex to bind to the von Willebrand factor, which in turn is what would help platelets adhere to a site of injury which eventually helps stop bleeding.[2]

Diagnosis

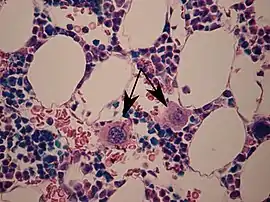

In terms of diagnosis Bernard–Soulier syndrome is characterized by prolonged bleeding time, thrombocytopenia, increased megakaryocytes, and enlarged platelets, Bernard–Soulier syndrome is associated with quantitative or qualitative defects of the platelet glycoprotein complex GPIb/V/IX. The degree of thrombocytopenia may be estimated incorrectly, due to the possibility that when the platelet count is performed with automatic counters, giant platelets may reach the size of red blood cells. The large platelets and low platelet count in BSS are seemingly due to the absence of GPIbα and the filamin A binding site that links the GPIb-IX-V complex to the platelet membrane skeleton.[5][8]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for Bernard–Soulier syndrome includes both Glanzmann thrombasthenia and pediatric Von Willebrand disease.[5] BSS platelets do not aggregate to ristocetin, and this defect is not corrected by the addition of normal plasma, distinguishing it from von Willebrand disease.[4] Following is a table comparing its result with other platelet aggregation disorders:

| ADP | Epinephrine | Collagen | Ristocetin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2Y receptor inhibitor or defect[9] | Decreased | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Adrenergic receptor defect[9] | Normal | Decreased | Normal | Normal |

| Collagen receptor defect[9] | Normal | Normal | Decreased or absent | Normal |

| Normal | Normal | Normal | Decreased or absent | |

| Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Normal or decreased |

Treatment

Bleeding events can be controlled by platelet transfusion. Most heterozygotes, with few exceptions, do not have a bleeding diathesis. BSS presents as a bleeding disorder due to the inability of platelets to bind and aggregate at sites of vascular endothelial injury.[4] In the event of an individual with mucosal bleeding tranexamic acid can be given.[5]

The affected individual may need to avoid contact sports and medications such as aspirin, which can increase the possibility of bleeding. A potential complication is the possibility of the individual producing anti-platelet antibodies.[10]

Prevalence

The frequency of Bernard–Soulier syndrome is approximately 1 in 1,000,000 people.[11] The syndrome, identified in the year 1948, is named after Dr. Jean Bernard and Dr. Jean Pierre Soulier.[12]

See also

References

- 1 2 Lanza F (2006). "Bernard-Soulier syndrome (hemorrhagiparous thrombocytic dystrophy)". Orphanet J Rare Dis. 1: 46. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-1-46. PMC 1660532. PMID 17109744.

- 1 2 Reference, Genetics Home. "Bernard-Soulier syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- 1 2 Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): GIANT PLATELET SYNDROME - 231200

- 1 2 3 Pham A, Wang J (2007). "Bernard-Soulier syndrome: an inherited platelet disorder". Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 131 (12): 1834–6. doi:10.5858/2007-131-1834-BSAIPD. PMID 18081445.

- 1 2 3 4 "Bernard-Soulier Syndrome: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology and Etiology". 2018-09-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Mhawech, Paulette; Saleem, Abdus (2000). "Inherited Giant Platelet Disorders". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 113 (2): 176–190. doi:10.1309/FC4H-LM5V-VCW8-DNJU. PMID 10664620.

- ↑ Dugdale, David. "Congenital platelet function defects". NIH. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ↑ Kanaji, T; Russell, S; Ware, J (Sep 15, 2002). "Amelioration of the macrothrombocytopenia associated with the murine Bernard-Soulier syndrome". Blood. 100 (6): 2102–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-03-0997. PMID 12200373. S2CID 25130678.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Borhany, Munira; Pahore, Zaen; ul Qadr, Zeeshan; Rehan, Muhammad; Naz, Arshi; Khan, Asif; Ansari, Saqib; Farzana, Tasneem; Nadeem, Muhammad; Raza, Syed Amir; Shamsi, Tahir (2010). "Bleeding disorders in the tribe: result of consanguineous in breeding". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 5 (1). doi:10.1186/1750-1172-5-23. ISSN 1750-1172. PMID 20822539.

- ↑ "Bernard-Soulier Syndrome; BSS & giant platelet information. Patient | Patient". Patient. 20 April 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ↑ RESERVED, INSERM US14 -- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Bernard Soulier syndrome". www.orpha.net. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Richmond, Caroline (10 June 2006). "Jean Bernard". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 332 (7554): 1395. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7554.1395. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1476743.

Further reading

- Berndt, Michael C.; Andrews, Robert K. (1 March 2011). "Bernard-Soulier syndrome". Haematologica. 96 (3): 355–359. doi:10.3324/haematol.2010.039883. ISSN 0390-6078. PMC 3046265. PMID 21357716.

- Bick, Rodger L. (2002). Disorders of Thrombosis and Hemostasis: Clinical and Laboratory Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780397516902. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- Turgeon, Mary Louise (2005). Clinical Hematology: Theory and Procedures (4th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781750073. Retrieved 17 July 2016.