As of May 2023, there have been 1,708 tropical cyclones of at least tropical storm intensity, 953 at hurricane intensity, and 330 at major hurricane intensity within the Atlantic Ocean since 1851, the first Atlantic hurricane season to be included in the official Atlantic tropical cyclone record.[1] Though a majority of these cyclones have fallen within climatological averages, prevailing atmospheric conditions occasionally lead to anomalous tropical systems which at times reach extremes in statistical record-keeping including in duration and intensity.[2] The scope of this list is limited to tropical cyclone records solely within the Atlantic Ocean and is subdivided by their reason for notability.

Tropical cyclogenesis

Most active / least active Atlantic hurricane seasons

Most Atlantic hurricane seasons prior to the weather satellite era include seven or fewer recorded tropical storms or hurricanes. As the usage of satellite data was not available until the mid-1960s, early storm counts are less reliable. Before the advent of the airplane or means of tracking storms, the ones recorded were storms that affected mainly populated areas. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated.[3]

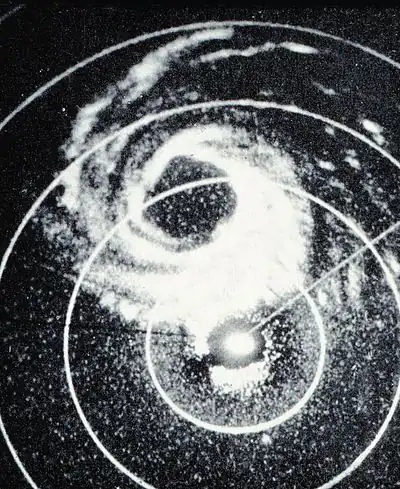

With the advent of the satellite came better and more accurate weather tracking. The first satellites sent into space to monitor the weather were known as Television Infrared Observation Satellites (TIROS). In 1961, Hurricane Esther was the first hurricane to be "discovered" through satellite readings.[4] Although this modern invention was now available, the systems were initially not fully active enough to provide daily images of the storms.[5] Data for the North Atlantic region remained sparse as late as 1964 due to a lack of complete satellite coverage.[6]

The most active Atlantic hurricane season on record in terms of total storms took place in 2020, with 30 documented. The storm count for the 2020 season also includes fourteen hurricanes, of which seven strengthened to major hurricane status. On the converse, the least active season on record in terms of total storms took place in 1914. The 1914 season had just one tropical storm and no hurricanes.

| Most storms in a year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Tropical storms | Hurricanes | ||

| Hurricanes | Major | |||

| 2020 | 30 * | 14 | 7 | |

| 2005 | 28 * | 15 | 7 | |

| 2021 | 21 * | 7 | 4 | |

| 1933 | 20 | 11 | 6 | |

| 2023 | 20 * | 7 | 3 | |

| 1887 | 19 | 11 | 2 | |

| 1995 | 19 | 11 | 5 | |

| 2010 | 19 | 12 | 5 | |

| 2011 | 19 | 7 | 4 | |

| 2012 | 19 | 10 | 2 | |

| * Includes at least one subtropical storm Source: [7] | ||||

| Fewest storms in a year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Tropical storms | Hurricanes | ||

| Hurricanes | Major | |||

| 1914 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1930 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |

| 1857 | 4 | 3 | 0 | |

| 1868 | 4 | 3 | 0 | |

| 1883 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |

| 1884 | 4 | 4 | 1 | |

| 1890 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| 1917 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| 1925 | 4 | 2 | 0 | |

| 1983 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| Source: [7] | ||||

Earliest / latest formations for each category

Climatologically speaking, approximately 97 percent of tropical cyclones that form in the North Atlantic develop between June 1 and November 30 – dates which delimit the modern-day Atlantic hurricane season. Though the beginning of the annual hurricane season has historically remained the same, the official end of the hurricane season has shifted from its initial date of October 31. Regardless, on average once every few years a tropical cyclone develops outside the limits of the season;[8] as of 2023 there have been 92 tropical cyclones in the off-season, with the most recent being an unnamed subtropical storm in January 2023. The first tropical cyclone of the 1938 Atlantic hurricane season, which formed on January 3, became the earliest forming tropical storm and hurricane after reanalysis concluded on the storm in December 2012.[9] Hurricane Able in 1951 was initially thought to be the earliest forming major hurricane;[nb 1] however, following post-storm analysis, it was determined that Able only reached Category 1 strength, which made Hurricane Alma of 1966 the new record holder, as it became a major hurricane on June 8.[11] Though it developed within the bounds of the Atlantic hurricane season,[8][11] Hurricane Audrey in 1957 was the earliest developing Category 4 hurricane on record after it reached the intensity on June 27.[12] However, reanalysis[11] of 1956 to 1960 by NOAA downgraded Audrey to a Category 3, making Hurricane Dennis of 2005 the earliest Category 4 on record on July 8, 2005.[13] The earliest-forming Category 5 hurricane, Emily, reached the highest intensity on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale on July 17, 2005.[14]

Though the official end of the Atlantic hurricane season occurs on November 30, the dates of October 31 and November 15 have also historically marked the official end date for the hurricane season.[8] December, the only month of the year after the hurricane season, has featured the cyclogenesis of fourteen tropical cyclones.[11] The second Hurricane Alice in 1954 was the latest forming tropical storm and hurricane, reaching these intensities on December 30 and 31, respectively. Hurricane Alice and Tropical Storm Zeta were the only two storms to exist in two calendar years – the former from 1954 to 1955 and the latter from 2005 to 2006.[15] No storms have been recorded to exceed Category 1 hurricane intensity in December.[11] In 1999, Hurricane Lenny reached Category 4 intensity on November 17 as it took an unusual west to east track across the Caribbean; its intensity made it the latest developing Category 4 hurricane, though this was well within the bounds of the hurricane season.[16] Based on reanalysis, the devastating "Cuba" hurricane in 1932 reached Category 5 intensity on November 5, making it the latest in any Atlantic hurricane season to reach this intensity.[11][9][nb 2]

| Earliest and latest forming Atlantic tropical / subtropical cyclones by Saffir–Simpson classification | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storm classification | Earliest formation | Latest formation | |||||

| Season | Storm | Date reached | Season | Storm | Date reached | ||

| Tropical depression | 1900 | One[19] | January 17 | 1954 | Alice[11] | December 30[nb 3] | |

| Tropical storm | 1938 | One[11] | January 3 | 1954 | Alice[11] | December 30[nb 4] | |

| Category 1 | 1938 | One[11] | January 4 | 1954 | Alice[11] | December 31 | |

| Category 2 | 1908 | One[11] | March 7 | 2016 | Otto[11] | November 24 | |

| Category 3 | 1966 | Alma[11] | June 8 | 2016 | Otto[11] | November 24 | |

| Category 4 | 2005 | Dennis[20] | July 8 | 1999 | Lenny[11] | November 17 | |

| Category 5 | 2005 | Emily[14][21] | July 17 | 1932 | "Cuba"[17] | November 5 | |

Most tropical / subtropical storms formed in each month

The Atlantic hurricane season presently runs from June 1 through November 30 each year, with peak activity occurring between August and October. Specifically, the height of the season is in early to mid-September.[8] Tropical systems that form outside of these months are referred to as "off season", and account for roughly 3% of all storms that form in a given year.[8] All of the records included below are for the most storms that formed in a given month, as the threshold for "fewest" is zero for expected months. Cases where "fewest storms" are unusual include the months when the hurricane season is at its peak.

| Number of Atlantic tropical / subtropical storm occurrences by month of naming | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Month | |||

| Most | Season | ||

| January | 1[22] | 1938, 1951, 1978, 2016, 2023 | |

| February | 1[23] | 1952[nb 5] | |

| March | 1[24] | 1908[nb 5] | |

| April | 1[22] | 1992, 2003, 2017 | |

| May | 2[22] | 1887, 2012, 2020 | |

| June | 3[22] | 1886, 1909, 1936, 1966, 1968, 2021, 2023 | |

| July | 5[25] | 2005, 2020 | |

| August | 8[22] | 2004, 2012 | |

| September | 10[26] | 2020 | |

| October | 8[22] | 1950 | |

| November | 3[27] | 1931, 1961, 1966, 2001, 2005, 2020 | |

| December | 2[22] | 1887, 2003 | |

Earliest formation records by storm number

| Earliest and next earliest forming Atlantic tropical / subtropical storms by storm number | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storm number |

Earliest | Next earliest | ||

| Name | Date of formation | Name | Date of formation | |

| 1 | One[11] | January 3, 1938 | One[11] | January 4, 1951 |

| 2 | Able[11] | May 16, 1951 | Two[11] | May 17, 1887 |

| 3 | Cristobal[28] | June 2, 2020 | Colin[28] | June 5, 2016 |

| 4 | Danielle[29] | June 20, 2016 | Cindy[29] | June 23, 2023[nb 6] |

| 5 | Elsa[30] | July 1, 2021 | Edouard[31] | July 6, 2020 |

| 6 | Fay[31] | July 9, 2020 | Franklin | July 21, 2005 |

| 7 | Gonzalo[32] | July 22, 2020 | Gert[32] | July 24, 2005 |

| 8 | Hanna[31] | July 24, 2020 | Harvey[31] | August 3, 2005 |

| 9 | Isaias[31] | July 30, 2020 | Irene[31] | August 7, 2005 |

| 10 | Josephine[31] | August 13, 2020 | Jose[31] | August 22, 2005 |

| 11 | Kyle[31] | August 14, 2020 | Katrina[31] | August 24, 2005 |

| 12 | Laura[31] | August 21, 2020 | Luis[31] | August 29, 1995 |

| 13 | Marco[33] | August 22, 2020 | Maria[33] | September 2, 2005[nb 7] |

| Lee[33] | September 2, 2011[nb 8] | |||

| 14 | Nana[34] | September 1, 2020 | Nate[34] | September 5, 2005 |

| 15 | Omar[35] | September 1, 2020 | Ophelia[35] | September 7, 2005[nb 9] |

| 16 | Paulette[36] | September 7, 2020 | Philippe[36] | September 17, 2005 |

| 17 | Rene[36] | September 7, 2020 | Rita[36] | September 18, 2005 |

| 18 | Sally[37] | September 12, 2020 | Sam[38] | September 23, 2021 |

| 19 | Teddy[39] | September 14, 2020 | Teresa[40] | September 24, 2021 |

| 20 | Vicky[41] | September 14, 2020 | Victor[42] | September 29, 2021 |

| 21 | Alpha[43] | September 17, 2020 | Vince | October 9, 2005 |

| 22 | Wilfred[43] | September 17, 2020 | Wilma | October 17, 2005 |

| 23 | Beta[44] | September 18, 2020 | Alpha[44] | October 22, 2005 |

| 24 | Gamma[45] | October 2, 2020 | Beta[45] | October 27, 2005 |

| 25 | Delta[46] | October 5, 2020 | Gamma[46] | November 15, 2005 |

| 26 | Epsilon[47] | October 19, 2020 | Delta[47] | November 22, 2005 |

| 27 | Zeta[48] | October 25, 2020 | Epsilon[49] | November 29, 2005 |

| 28 | Eta[50] | November 1, 2020 | Zeta[51] | December 30, 2005 |

| 29 | Theta[52] | November 10, 2020 | Earliest formation by virtue of being the only of that number | |

| 30 | Iota[53] | November 13, 2020 | ||

Intensity

Most intense

Generally speaking, the intensity of a tropical cyclone is determined by either the storm's maximum sustained winds or lowest barometric pressure. The following table lists the most intense Atlantic hurricanes in terms of their lowest barometric pressure. In terms of wind speed, Allen from 1980 was the strongest Atlantic tropical cyclone on record, with maximum sustained winds of 190 mph (310 km/h). For many years, it was thought that Hurricane Camille also attained this intensity, but this conclusion was changed in 2014. The original measurements of Camille are suspect since wind speed instrumentation used at the time would likely be damaged by winds of such intensity.[54] Nonetheless, their central pressures are low enough to rank them among the strongest recorded Atlantic hurricanes.[11]

Owing to their intensity, the strongest Atlantic hurricanes have all attained Category 5 classification. Hurricane Opal, the most intense Category 4 hurricane recorded, intensified to reach a minimum pressure of 916 mbar (hPa; 27.05 inHg),[55] a pressure typical of Category 5 hurricanes.[56] Nonetheless, the pressure remains too high to list Opal as one of the ten strongest Atlantic tropical cyclones.[11] Currently, Hurricane Wilma is the strongest Atlantic hurricane ever recorded, after reaching an intensity of 882 mbar (hPa; 26.05 inHg) in October 2005;[54] at the time, this also made Wilma the strongest tropical cyclone worldwide outside of the West Pacific,[57][58][59][60][61] where seven tropical cyclones have been recorded to intensify to lower pressures.[62] However, this was later superseded by Hurricane Patricia in 2015 in the east Pacific, which had a pressure reading of 872 mbar. Preceding Wilma is Hurricane Gilbert, which had also held the record for most intense Atlantic hurricane for 17 years.[63] The 1935 Labor Day hurricane, with a pressure of 892 mbar (hPa; 26.34 inHg), is the third strongest Atlantic hurricane and the strongest documented tropical cyclone prior to 1950.[11] Since the measurements taken during Wilma and Gilbert were documented using dropsonde, this pressure remains the lowest measured over land.[64]

Hurricane Rita is the fourth strongest Atlantic hurricane in terms of barometric pressure and one of three tropical cyclones from 2005 on the list, with the others being Wilma and Katrina at first and seventh, respectively.[11] However, with a barometric pressure of 895 mbar (hPa; 26.43 inHg), Rita is the strongest tropical cyclone ever recorded in the Gulf of Mexico.[65] In between Rita and Katrina is Hurricane Allen. Allen's pressure was measured at 899 mbar. Hurricane Camille is the sixth strongest hurricane on record. Camille is the only storm to have been moved down the list due to post-storm analysis. Camille was originally recognized as the fifth strongest hurricane on record, but was dropped to the seventh strongest in 2014, with an estimated pressure at 905 mbars, tying it with Hurricanes Mitch, and Dean. Camille then was recategorized with a new pressure of 900 mbars. Currently, Mitch and Dean share intensities for the eighth strongest Atlantic hurricane at 905 mbar (hPa; 26.73 inHg).[64] Hurricane Maria is in tenth place for most intense Atlantic tropical cyclone, with a pressure as low as 908 mbar (hPa; 26.81 inHg).[66] In addition, the most intense Atlantic hurricane outside of the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico is Hurricane Dorian of 2019, with a pressure of 910 mbar (hPa; 26.9 inHg).[67]

Many of the strongest recorded tropical cyclones weakened prior to their eventual landfall or demise. However, four of the storms remained intense enough at landfall to be considered some of the strongest landfalling hurricanes – four of the ten hurricanes on the list constitute four of the top ten most intense Atlantic landfalls in recorded history. The 1935 Labor Day hurricane made landfall at peak intensity, the most intense Atlantic hurricane landfall.[68] Hurricane Camille made landfall in Waveland, Mississippi with a pressure of 900 mbar (hPa; 26.58 inHg), making it the second most intense Atlantic hurricane landfall.[69] Though it weakened slightly before its eventual landfall on the Yucatán Peninsula, Hurricane Gilbert maintained a pressure of 900 mbar (hPa; 26.58 inHg) at landfall, making its landfall the second strongest, tied with Camille. Similarly, Hurricane Dean made landfall on the peninsula, though it did so at peak intensity and with a higher barometric pressure; its landfall marked the fourth strongest in Atlantic hurricane history.[64]

- Note: Dropsondes have only been GPS-based for use in eyewalls since 1997,[70] and the quantity of aircraft reconnaissance and surface observation stations has changed over time, such that values from storms in different periods may not be 100% consistent.

Most intense by minimum barometric pressure

| Most intense Atlantic hurricanes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hurricane | Season | By peak pressure | By pressure at landfall | ||

| mbar | inHg | mbar | inHg | ||

| Wilma | 2005 | 882 | 26.05 | ||

| Gilbert | 1988 | 888 | 26.22 | 900 | 26.58 |

| "Labor Day" | 1935 | 892 | 26.34 | 892 | 26.34 |

| Rita | 2005 | 895 | 26.43 | ||

| Allen | 1980 | 899 | 26.55 | ||

| Camille | 1969 | 900 | 26.58 | 900 | 26.58 |

| Katrina | 2005 | 902 | 26.64 | ||

| Mitch | 1998 | 905 | 26.72 | ||

| Dean | 2007 | 905 | 26.72 | 905 | 26.72 |

| Maria | 2017 | 908 | 26.81 | ||

| "Cuba" | 1924 | 910 | 26.87 | ||

| Dorian | 2019 | 910 | 26.87 | ||

| Janet | 1955 | 914 | 26.99 | ||

| Irma | 2017 | 914 | 26.99 | ||

| "Cuba" | 1932 | 918 | 27.10 | ||

| Michael | 2018 | 919 | 27.14 | ||

| Note: Grey shading indicates that the pressure was not a record, only the top ten storms for each category are included here. | |||||

Strongest by 1-minute sustained wind speed

| Strongest Atlantic hurricanes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hurricane | Season | By peak sustained wind speed | By wind speed at landfall | ||

| mph | km/h | mph | km/h | ||

| Allen | 1980 | 190 | 305 | ||

| "Labor Day" | 1935 | 185 | 295 | 185 | 295 |

| Gilbert | 1988 | 185 | 295 | ||

| Dorian | 2019 | 185 | 295 | 185 | 295 |

| Wilma | 2005 | 185 | 295 | ||

| Mitch | 1998 | 180 | 285 | ||

| Rita | 2005 | 180 | 285 | ||

| Irma | 2017 | 180 | 285 | 180 | 285 |

| "Cuba" | 1932 | 175 | 280 | ||

| Janet | 1955 | 175 | 280 | 175 | 280 |

| Camille | 1969 | 175 | 280 | 175 | 280 |

| Anita | 1977 | 175 | 280 | 175 | 280 |

| David | 1979 | 175 | 280 | 175 | 280 |

| Andrew | 1992 | 175 | 280 | 165 | 270 |

| Katrina | 2005 | 175 | 280 | ||

| Dean | 2007 | 175 | 280 | 175 | 280 |

| Felix | 2007 | 175 | 280 | 165 | 270 |

| Maria | 2017 | 175 | 280 | 165 | 270 |

| Note: Grey shading indicates that the wind speed was not a record, only the highest ranking storms for each category are included here. | |||||

Hurricane Severity Index

| Most severe landfalling Atlantic hurricanes in the United States Based on size and intensity for total points on the Hurricane Severity Index[71] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Year | Intensity | Size | Total |

| 1 | 4 Carla | 1961 | 17 | 25 | 42 |

| 2 | 4 Betsy | 1965 | 15 | 25 | 40 |

| 3 | 5 Camille | 1969 | 22 | 14 | 36 |

| 4 Opal | 1995 | 11 | 25 | 36 | |

| 5 Katrina | 2005 | 13 | 23 | 36 | |

| 6 | 3 Audrey | 1957 | 17 | 16 | 33 |

| 5 Wilma | 2005 | 12 | 21 | 33 | |

| 8 | 5 Ivan | 2004 | 12 | 20 | 32 |

| 9 | 4 Ike | 2008 | 10 | 20 | 30 |

| 10 | 5 Andrew | 1992 | 16 | 11 | 27 |

Chicago Mercantile Exchange Hurricane Index

| Most severe landfalling Atlantic hurricanes in the United States Based on size and intensity for total points on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange Hurricane Index[72] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Year | Landfall | Windspeed at/near landfall (operational) |

Radius of hurricane–force winds at/near landfall |

CMEHI index |

| 1 | 4 Hugo* | 1989 | South Carolina | 140 mph (220 km/h) | 140 mi (225 km) | 19.3 |

| 2 | 4 Katrina* | 2005 | Louisiana | 145 mph (230 km/h) | 120 mi (195 km) | 19.0 |

| 3 | 4 Maria | 2017 | Puerto Rico | 155 mph (250 km/h) | 60 mi (95 km) | 15.8 |

| 4 | 4 Laura | 2020 | Louisiana | 150 mph (240 km/h) | 60 mi (95 km) | 14.5 |

| 5 | 3 Fran | 1996 | North Carolina | 115 mph (185 km/h) | 175 mi (280 km) | 14.3 |

| 6 | 4 Michael | 2018 | Florida | 155 mph (250 km/h) | 45 mi (70 km) | 14.1 |

| 4 Ian* | 2022 | Florida | 155 mph (250 km/h) | 45 mi (70 km) | 14.1 | |

| 8 | 4 Ivan | 2004 | Alabama | 130 mph (215 km/h) | 105 mi (170 km) | 13.5 |

| 4 Ida | 2021 | Louisiana | 150 mph (240 km/h) | 50 mi (80 km) | 13.5 | |

| 10 | 4 Irma | 2017 | Florida | 130 mph (215 km/h) | 80 mi (130 km) | 11.6 |

| Note: * Indicates that the storm made landfall as a hurricane in multiple regions of the U.S., therefore only the highest index is listed | ||||||

Fastest intensification

- Fastest intensification from a tropical depression to a hurricane (1-minute sustained surface winds) – 12 hours

Harvey 1981 – 35 mph (55 km/h) to 80 mph (130 km/h) – from 1200 UTC September 12 to 0000 UTC September 13[11] - Fastest intensification from a tropical depression to a Category 5 hurricane (1-minute sustained surface winds) – 54 hours

Wilma 2005 – 35 mph (55 km/h) to 175 mph (280 km/h) – from 0000 UTC October 17 to 0600 UTC October 19[11]

Felix 2007 – 35 mph (55 km/h) to 175 mph (280 km/h) – from 1800 UTC August 31 to 0000 UTC September 3[11] - Fastest intensification from a tropical storm to a Category 5 hurricane (1-minute sustained surface winds) – 24 hours

Wilma 2005 – 70 mph (110 km/h) to 175 mph (275 km/h) – from 0600 UTC October 18 to 0600 UTC October 19[11] - Maximum pressure drop in 12 hours – 83 mbar

Wilma 2005 – 975 millibars (28.8 inHg) to 892 millibars (26.3 inHg) – from 1800 UTC October 18 to 0600 UTC October 19[11] - Maximum pressure drop in 24 hours – 97 mbar

Wilma 2005 – 979 millibars (28.9 inHg) to 882 millibars (26.0 inHg) – from 1200 UTC October 18 to 1200 UTC October 19[11]

Effects

Costliest Atlantic hurricanes

| Costliest Atlantic hurricanes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Damage[nb 10] |

| 1 | 5 Katrina | 2005 | $125 billion |

| 4 Harvey | 2017 | ||

| 3 | 5 Ian | 2022 | $113 billion |

| 4 | 5 Maria | 2017 | $91.6 billion |

| 5 | 5 Irma | 2017 | $77.2 billion |

| 6 | 4 Ida | 2021 | $75.3 billion |

| 7 | 3 Sandy | 2012 | $68.7 billion |

| 8 | 4 Ike | 2008 | $38 billion |

| 9 | 5 Andrew | 1992 | $27.3 billion |

| 10 | 5 Ivan | 2004 | $26.1 billion |

Deadliest Atlantic hurricanes

| Deadliest Atlantic hurricanes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Fatalities |

| 1 | ? "Great Hurricane" | 1780 | 22,000–27,501 |

| 2 | 5 Mitch | 1998 | 11,374+ |

| 3 | 2 Fifi | 1974 | 8,210–10,000 |

| 4 | 4 "Galveston" | 1900 | 8,000–12,000 |

| 5 | 4 Flora | 1963 | 7,193 |

| 6 | ? "Pointe-à-Pitre" | 1776 | 6,000+ |

| 7 | 5 "Okeechobee" | 1928 | 4,112+ |

| 8 | ? "Newfoundland" | 1775 | 4,000–4,163 |

| 9 | 3 "Monterrey" | 1909 | 4,000 |

| 10 | 4 "San Ciriaco" | 1899 | 3,855 |

Most tornadoes spawned

| Number of tornadoes spawned[73] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Count | Name | Year |

| 1 | 120 | 5 Ivan | 2004 |

| 2 | 115 | 5 Beulah | 1967 |

| 3 | 103[74] | 4 Frances | 2004 |

| 4 | 101 | 5 Rita | 2005 |

| 5 | 57 | 5 Katrina | 2005 |

| 6 | 54 | 4 Harvey | 2017 |

| 7 | 50 | TS Fay | 2008 |

| 8 | 49 | 4 Gustav | 2008 |

| 9 | 47 | 4 Georges | 1998 |

| 10 | 46[75] | TS Lee | 2011 |

Miscellaneous records

| Miscellaneous records | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Record | Value | Name | Season |

| Distance traveled | 6,500 miles (10,500 km)[76] | 3 Alberto | 2000 |

| Highest forward speed | 69 mph (111 km/h)[11][77] | TS Six | 1961 |

| Largest in diameter | 1,150 miles (1,850 km)[78] | 3 Sandy | 2012 |

| Longest duration (non consecutive) | 28 days[11][79][80] | 4 "San Ciriaco" | 1899 |

| Longest duration (consecutive) | 27.25 days[11][79][80] | 2 Ginger | 1971 |

| Longest duration (at category 5) | 3.6 days[81] | 5 "Cuba" | 1932 |

| Northernmost tropical cyclone formation | 42.0°N; 23.0°W [11] | TS Five | 1952 |

| Southernmost tropical cyclone formation | 7.2°N; 23.4°W [11] | 2 Isidore | 1990 |

| Easternmost tropical cyclone formation | 11.0°N, 14.0°W [11] | TS Christine | 1973 |

| Westernmost tropical cyclone formation | 22.4°N, 97.4°W [11] | TD Eight | 2013 |

Worldwide cyclone records set by Atlantic storms

- Costliest tropical cyclone: Hurricane Katrina – 2005 and Hurricane Harvey – 2017 – US$125 billion in damages

- Fastest seafloor current produced by a tropical cyclone: Hurricane Ivan – 2004 – 2.25 m/s (5 mph)[82][83]

- Highest confirmed wave produced by a tropical cyclone: Hurricane Luis – 1995 – 98 feet (30 m)[84]

- Highest forward speed of a tropical cyclone: Tropical Storm Six – 1961 – 69 mph (111 km/h)

- Most tornadoes spawned by a tropical cyclone: Hurricane Ivan – 2004 – 120 confirmed tornadoes[85]

- Smallest tropical cyclone on record: Tropical Storm Marco – 2008 – gale-force winds extended 11.5 mi (18.5 km) from storm center (previous record: Cyclone Tracy 1974 – 30 mi (48 km))

- Smallest tropical cyclone eye on record: Hurricane Wilma – 2005 – diameter 2.3 miles (3.7 km)

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hurricanes reaching Category 3 (111 mph (179 km/h)) and higher on the 5-level Saffir–Simpson wind speed scale are considered major hurricanes.[10]

- ↑ Although Hurricane Iota in 2020 was operationally analyzed to be a Category 5 hurricane,[17] its peak strength was revised down to Category 4 in the post-season analysis.[18]

- ↑ 1954's Hurricane Alice and 2005's Tropical Storm Zeta both formed as tropical depressions on December 30; however, Alice formed around 06:00 UTC, about six hours later than Zeta.[11]

- ↑ 1954's Hurricane Alice and 2005's Tropical Storm Zeta both became tropical storms on December 30; however, Alice became a tropical storm around 12:00 UTC, about six hours later than Zeta.[11]

- 1 2 Highest number for month by virtue of being the only season on record to have a storm form during that month.

- ↑ 2020's Dolly and 2023's Cindy both formed on June 23; however, Cindy became a tropical storm around 3:00 UTC, about three hours before Dolly.

- ↑ 2005's Maria and 2011's Lee both formed on September 2 and each became a tropical storm around 12:00 UTC.

- ↑ 2011's Lee and 2005's Maria both formed on September 2 and each became a tropical storm around 12:00 UTC.

- ↑ 2005's Ophelia and 2011's Nate both formed on September 7; however, Ophelia became a tropical storm around 06:00 UTC, about 12 hours before Nate.

- ↑ All damage figures are in United States dollars, and are not adjusted for inflation.

References

- ↑ "North Atlantic Ocean Historical Tropical Cyclone Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Department of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Climatology". Miami, Florida: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ↑ Landsea, C. W. (2004). "The Atlantic hurricane database re-analysis project: Documentation for the 1851–1910 alterations and additions to the HURDAT database". In Murname, R. J.; Liu, K.-B. (eds.). Hurricanes and Typhoons: Past, Present and Future. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 177–221. ISBN 0-231-12388-4.

- ↑ Cortright, Edgar M., ed. (1968). "Section One: Above The Atmosphere". Exploring Space With A Camera. Washington, D.C.: NASA History Office. Bibcode:1968eswc.book.....C. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ↑ Staff writer (June 13, 1962). "Hurricane Season Upon Us". The Windsor Star. United Press International. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ↑ Neil L. Frank; H. M. Johnson (February 1969). "Vortical Cloud Systems Over the Tropical Atlantic During the 1967 Atlantic Hurricane Season" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 97 (2): 125. Bibcode:1969MWRv...97..124F. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1969)097<0124:vcsott>2.3.co;2. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- 1 2 "North Atlantic Ocean Historical Tropical Cyclone Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dorst, Neal (June 1, 2018). "Hurricane Season Information". Frequently Asked Questions About Hurricanes. Miami, Florida: NOAA Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- 1 2 Landsea, Chris; et al. (June 2013). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "1957 – Hurricane Audrey". hurricanescience.org. University of Rhode Island. Retrieved September 3, 2013.

- ↑ NHC Public Affairs (July 20, 2016). "Reanalysis of 1956 to 1960 Atlantic hurricane seasons completed: 10 new tropical storms discovered" (PDF). nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- 1 2 Franklin, James L.; Brown, Daniel P. (March 10, 2006). Hurricane Emily (PDF). National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report (Report). Miami, Florida: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 24, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2013.

- ↑ Hurricane.com. "Atlantic Hurricane and Tropical Storm Records". Hurricane.com. Archived from the original on March 14, 2006. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ↑ Chambers, Gillan (December 1999). "Late Hurricanes: a Message for the Region". Environment and development in coastal regions and in small islands. Coast and Beach Stability in the Lesser Antilles. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- 1 2 Eric Blake. "Hurricane Iota Discussion Number 13". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (May 18, 2021). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Iota (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 9, 2021. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ↑ Christopher W. Landsea; et al. Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ↑ Courson, Paul (August 26, 2005). "NOAA: More hurricanes to come". CNN. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ↑ Beven, John L.; Avila, Lixion A.; Blake, Eric S.; Brown, Daniel P.; Franklin, James L.; Knabb, Richard D.; Pasch, Richard J.; Rhome, Jamie R.; Stewart, Stacy R. (March 2008). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 2005" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Monthly Weather Review Atlantic Hurricane Season Summary. 136 (3): 1109–1173. Bibcode:2008MWRv..136.1109B. doi:10.1175/2007MWR2074.1. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 U.S. NOAA Coastal Service Center – Historical Hurricane Tracks Tool

- ↑ Erdman, Jonathan (January 31, 2020). "Yes, There Was Once a February Tropical Storm Off the East Coast". weather.com. The Weather Channel. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ Erdman, Jonathan (March 8, 2020). "Yes, There Was Once a March Atlantic Hurricane". weather.com. The Weather Channel. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ "State of the Climate: Hurricanes and Tropical Storms for July 2020". NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. August 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ Dolce, Chris (October 6, 2020). "All the Records the 2020 Hurricane Season has Broken So Far". weather.com. The Weather Channel. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ Philip Klotzbach [@philklotzbach] (November 14, 2020). "#Iota is the 3rd Atlantic named storm to form this November, along with Eta and #Theta" (Tweet). Retrieved November 14, 2020 – via Twitter.

- 1 2 Gray, Jennifer (June 2, 2020). "Cristobal becomes the earliest third Atlantic named storm on record". CNN. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- 1 2 Henson, Bob (June 23, 2023). "Unusual June Tropical Storms Bret and Cindy stir up the Atlantic". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ↑ Andrew Dockery. "Fifth named storm of the 2021 hurricane season and is now the earliest "E" named storm on record". www.wmbfnews.com. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Martucci, Joe (August 25, 2020). "Hurricane Laura continues record hurricane season pace, here's the forecast". The Press of Atlantic City. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- 1 2 Prociv, Kathryn (July 22, 2020). "Tropical Storm Gonzalo forecast to become 2020's first Atlantic hurricane of the year". NBC News. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Bellafiore, Sean (August 21, 2020). "Tropical Depression 14 not yet a tropical storm, could threaten Central Texas". Waco, Texas: KWTX News. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- 1 2 Cappucci, Matthew (September 1, 2020). "Tropical storm Nana nears formation in Caribbean as Atlantic hurricane season stays unusually active". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- 1 2 "Tropical Storm Omar, Record Earliest Fifteenth Storm, Tracking Well Off the U.S. East Coast". weather.com. The Weather Channel. September 1, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Erdman, Jonathan (September 7, 2020). "Tropical Storm Paulette, Record Earliest 16th Storm, Forms in Eastern Atlantic While Tropical Storm Rene is Soon to Follow". weather.com. The Weather Channel. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ↑ Niles, Nancy; Hauck, Grace; Aretakis, Rachel (September 12, 2020). "Tropical Storm Sally forms as it crosses South Florida; likely to strengthen into hurricane when it reaches Gulf". USA Today Network. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ↑ Masters, Jeff (September 23, 2021). "Tropical Storm Sam forms in central tropical Atlantic". New Haven Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ↑ Marchante, Michelle; Harris, Alex (September 14, 2020). "With newly formed Tropical Storm Teddy, NHC tracking five named systems at once". The Miami Herald. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ↑ Masters, Jeff (September 25, 2021). "Sam rapidly intensifies into a major category 3 hurricane". New Haven Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ↑ Michals, Chris (September 14, 2020). "Sally takes aim at the Gulf Coast; only one name left for hurricane season". wsls.com. Roanoke, Virginia: WSLS-TV. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ↑ Masters, Jeff; Henson, Bob (September 30, 2021). "Tropical Storm Victor joins category 4 Hurricane Sam in the Atlantic". New Haven Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- 1 2 Borenstein, Seth (September 18, 2020). "Running out of storm names, Atlantic season goes Greek". Chattanooga Times Free Press. Chattanooga, Tennessee. AP. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- 1 2 Bacon, John; Falcon, Meagan (September 20, 2020). "Texas prepares water rescue teams as Tropical Storm Beta threatens 'torrential rainfall'". USA Today. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- 1 2 Discher, Emma (October 2, 2020). "Tropical Storm Gamma develops over Caribbean Sea; here's the latest forecast". nola.com. New Orleans, Louisiana. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- 1 2 Morgan, Leigh (October 5, 2020). "Tropical Storm Delta forms and is headed for the Gulf Coast later this week - as a hurricane". al.com. The Birmingham News. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- 1 2 Masters, Jeff (October 19, 2020). "Tropical Storm Epsilon forms in the central Atlantic". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ↑ "UPDATE: Tropical Storm Zeta forms near Cuba; Georgia in cone". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. AP. October 25, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ↑ Shepherd, Marshall (October 23, 2020). "Zeta May Be Forming In The Caribbean - Why That's Odd (And Not)". forbes.com. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Eta ties record; expected to become hurricane". abcnews.go.com. ABC News Internet Ventures. AP. November 1, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ↑ Cappucci, Matthew (October 30, 2020). "Tropical Storm Eta likely to form in Caribbean to start potentially busy November in the tropics". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ↑ Cappucci, Matthew (November 9, 2020). "The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season is busiest on record as Subtropical Storm Theta forms". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ↑ Rice, Doyle (November 13, 2020). "Eta, Theta and now Iota: Tropical storm forecast to approach Central America as a hurricane next week". usatoday.com. USA Today. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- 1 2 Landsea, Chris (April 21, 2010). "E1) Which is the most intense tropical cyclone on record?". Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). 4.6. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ↑ Mayfield, Max (November 29, 1995). Hurricane Opal Preliminary Report (Preliminary Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ↑ Louisiana Geographic Information Center. "The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale". Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center (April 4, 2023). "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2022". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Best Track Information for the North Indian Ocean 1990-2008". India Meteorological Department. 2009. Archived from the original (XLS) on 16 November 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ↑ Royer, Stephane (7 February 2003). "Very Intense Tropical Cyclone Gafilo". Météo France. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Information for the Australian Region". Bureau of Meteorology. 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ MetService (May 22, 2009). "TCWC Wellington Best Track Data 1967–2006". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship.

- ↑ "Western North Pacific Typhoon best track file 1951-2024". Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ↑ Willoughby, H.E.; Masters, J. M.; Landsea, C. W. (December 1, 1989). "A Record Minimum Sea Level Pressure Observed in Hurricane Gilbert". Monthly Weather Review. 117 (12): 2824–2828. Bibcode:1989MWRv..117.2824W. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<2824:ARMSLP>2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 Franklin, James L. (January 31, 2008). "Hurricane Dean" (PDF). National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Reports. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ↑ National Weather Service (November 14, 2005). "Post Storm Data Acquisition – Hurricane Rita Peak Gust Analysis and Storm Surge Data" (PDF). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ↑ Brown, Daniel. "Hurricane Maria Intermediate Advisory Number 15A". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (September 1, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Forecast Discussion Number 34". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ↑ Bob Henson (September 6, 2017). "Category 5 Irma Hits Leeward Islands at Peak Strength". Weather Underground. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ↑ R.H. Simpson; Arnold L. Sugg (April 1970). "The Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1969" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 98 (4): 293. Bibcode:1970MWRv...98..293S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493-98.4.293. S2CID 123713109. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ↑ "AVAPS Dropsonde System | Earth Observing Laboratory". Eol.ucar.edu. Retrieved 2020-10-07.

- ↑ Hurricane Severity Index

- ↑

- ↑ Grazulis, Thomas P. (1993). "11". Significant Tornadoes 1680-1991, A Chronology and Analysis of Events. St. Johnsbury, VT: The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. pp. 124–127. ISBN 978-1-879362-03-1.

- ↑ John L. Beven II. Hurricane Frances. Retrieved on 2007-04-08.

- ↑ Brown, Daniel P (December 15, 2011). Tropical Storm Lee (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Hurricane Center. pp. 4–5. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ↑ Neal Dorst; Sandy Delgado (May 20, 2011). "Subject: E7) What is the farthest a tropical cyclone has traveled ?". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- ↑ "What is the average forward speed of a hurricane? (G16)". Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ↑ "Hurricane Sandy Grows to Largest Atlantic Tropical Storm Ever". 28 October 2012.

- 1 2 Neal Dorst (January 26, 2010). "Subject: E6) Which tropical cyclone lasted the longest?". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on September 24, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- 1 2 Lixion Avila & Robbie Berg (October 4, 2012). "Remnants of Nadine Discussion Eighty-Eight (Final)". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- ↑ Daniel Brown; Chris Landsea (September 5, 2017). Hurricane Irma Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Hurricane Ivan Uncovered a 60,000 year old Cypress Forest in the Gulf of Mexico". WordPress.com. 9 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ↑ "Hurricane and Storm Shutters in Gulf Shores Alabama". Hurricane Shutters Florida. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ↑ Staff Writer (2004). "Extremes of Weather: Horrifying hurricanes". The Canadian Atlas. Archived from the original on August 2, 2009. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ↑ "What is the largest known outbreak of tropical cyclone tornadoes?". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved 28 August 2018.