Tadao Ando | |

|---|---|

Tadao Ando in 2004 | |

| Born | 13 September 1941 Minato-ku, Osaka, Japan |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards |

|

| Practice | Tadao Ando Architects & Associates |

| Buildings |

|

| Projects | Rokko Housing I, II, III, Kobe, 1983–1999 |

Tadao Ando (安藤 忠雄, Andō Tadao, born 13 September 1941) is a Japanese autodidact architect[1][2] whose approach to architecture and landscape was categorized by architectural historian Francesco Dal Co as "critical regionalism". He is the winner of the 1995 Pritzker Prize.

Early life

Ando was born a few minutes before his twin brother in 1941 in Minato-ku, Osaka, Japan.[3] At the age of two, his family chose to separate them and have Tadao live with his great-grandmother.[3] He worked as a boxer and fighter before settling on the profession of architect, despite never having formal training in the field. Struck by the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Imperial Hotel on a trip to Tokyo as a second-year high school student, he eventually decided to end his boxing career less than two years after graduating from high school to pursue architecture.[4] He attended night classes to learn drawing and took correspondence courses on interior design.[5] He visited buildings designed by renowned architects like Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Louis Kahn before returning to Osaka in 1968 to establish his own design studio, Tadao Ando Architects and Associates.[6]

Career

Style

Ando was raised in Japan where the religion and style of life strongly influenced his architecture and design. Ando's architectural style is said to create a "haiku" effect, emphasizing nothingness and empty space to represent the beauty of simplicity. He favors designing complex spatial circulation while maintaining the appearance of simplicity. A self-taught architect, he keeps his Japanese culture and language in mind while he travels around Europe for research. As an architect, he believes that architecture can change society, that "to change the dwelling is to change the city and to reform society".[7] "Reform society" could be a promotion of a place or a change of the identity of that place. Werner Blaser has said, "Good buildings by Tadao Ando create memorable identity and therefore publicity, which in turn attracts the public and promotes market penetration".[8]

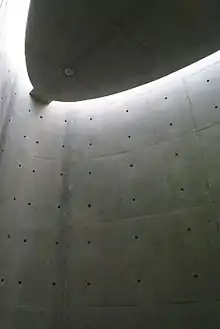

The simplicity of his architecture emphasizes the concept of sensation and physical experiences, mainly influenced by Japanese culture. The religious term Zen, focuses on the concept of simplicity and concentrates on inner feeling rather than outward appearance. Zen influences vividly show in Ando's work and became its distinguishing mark. In order to practice the idea of simplicity, Ando's architecture is mostly constructed with concrete, providing a sense of cleanliness and weightlessness (even though concrete is a heavy material) at the same time.[9] Due to the simplicity of the exterior, construction, and organization of the space are relatively potential in order to represent the aesthetic of sensation.

Besides Japanese religious architecture, Ando has also designed Christian churches, such as the Church of the Light (1989) and the Church in Tarumi (1993).[10] Although Japanese and Christian churches display distinct characteristics, Ando treats them in a similar way. He believes there should be no difference in designing religious architecture and houses. As he explains,

We do not need to differentiate one from the other. Dwelling in a house is not only a functional issue, but also a spiritual one. The house is the locus of heart (kokoro), and the heart is the locus of god. Dwelling in a house is a search for the heart (kokoro) as the locus of god, just as one goes to church to search for god. An important role of the church is to enhance this sense of the spiritual. In a spiritual place, people find peace in their heart (kokoro), as in their homeland.[11]

Besides speaking of the spirit of architecture, Ando also emphasises the association between nature and architecture.[12][13] He intends for people to easily experience the spirit and beauty of nature through architecture. He believes architecture is responsible for performing the attitude of the site and makes it visible. This not only represents his theory of the role of architecture in society but also shows why he spends so much time studying architecture from physical experience.

In 1995, Ando won the Pritzker Prize for architecture, considered the highest distinction in the field.[2] He donated the $100,000 prize money to the orphans of the 1995 Kobe earthquake.[14]

Buildings and works

Tadao Ando's body of work is known for the creative use of natural light and for structures that follow natural forms of the landscape, rather than disturbing the landscape by making it conform to the constructed space of a building. Ando's buildings are often characterized by complex three-dimensional circulation paths. These paths weave in between interior and exterior spaces formed both inside large-scale geometric shapes and in the spaces between them.

His "Row House in Sumiyoshi" (Azuma House, 住吉の長屋), a small two-story, cast-in-place concrete house completed in 1976, is an early work which began to show elements of his characteristic style. It consists of three equal rectangular volumes: two enclosed volumes of interior spaces separated by an open courtyard. The courtyard's position between the two interior volumes becomes an integral part of the house's circulation system. The house is famous for the contrast between appearance and spatial organization which allow people to experience the richness of the space within the geometry.[15]

Ando's housing complex at Rokko, just outside Kobe, is a complex warren of terraces and balconies, atriums and shafts. The designs for Rokko Housing One (1983) and for Rokko Housing Two (1993) illustrate a range of issues in traditional architectural vocabulary—the interplay of solid and void, the alternatives of open and closed, the contrasts of light and darkness. More significantly, Ando's noteworthy engineering achievement in these clustered buildings is site specific—the structures survived undamaged after the Great Hanshin earthquake of 1995.[16] New York Times architectural critic Paul Goldberger argues that:

Ando is right in the Japanese tradition: spareness has always been a part of Japanese architecture, at least since the 16th century; [and] it is not without reason that Frank Lloyd Wright more freely admitted to the influences of Japanese architecture than of anything American."[16]

Like Wright's Imperial Hotel in Tokyo Second Imperial Hotel 1923-1968, which did survive the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923, site specific decision-making, anticipates seismic activity in several of Ando's Hyōgo-Awaji buildings.[17]

Projects

| Building/project | Location | Country | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tomishima House | Osaka | Japan | 1973 |

| Uchida House | Japan | 1974 | |

| Uno House | Kyoto | Japan | 1974 |

| Hiraoka House | Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1974 |

| Shibata House | Ashiya, Hyogo Prefecture | Japan | 1974 |

| Tatsumi House | Osaka | Japan | 1975 |

| Soseikan-Yamaguchi House | Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1975 |

| Takahashi House | Ashiya, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1975 |

| Matsumura House | Kobe | Japan | 1975 |

| Row House in Sumiyoshi (Azuma House) | Sumiyoshi, Osaka | Japan | 1976 |

| Hirabayashi House | Osaka Prefecture | Japan | 1976 |

| Bansho House | Aichi Prefecture | Japan | 1976 |

| Tezukayama Tower Plaza | Sumiyoshi, Osaka | Japan | 1976 |

| Tezukayama House-Manabe House | Osaka | Japan | 1977 |

| Wall House (Matsumoto House) | Ashiya, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1977 |

| Glass Block House (Ishihara House) | Osaka | Japan | 1978 |

| Okusu House | Setagaya, Tokyo | Japan | 1978 |

| Glass Block Wall (Horiuchi House) | Sumiyoshi, Osaka | Japan | 1979 |

| Katayama Building | Nishinomiya, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1979 |

| Onishi House | Sumiyoshi, Osaka | Japan | 1979 |

| Matsutani House | Kyoto | Japan | 1979 |

| Ueda House | Okayama Prefecture | Japan | 1979 |

| Step | Takamatsu, Kagawa | Japan | 1980 |

| Matsumoto House | Wakayama, Wakayama Prefecture | Japan | 1980 |

| Fuku House | Wakayama, Wakayama Prefecture | Japan | 1980 |

| Bansho House Addition | Aichi Prefecture | Japan | 1981 |

| Koshino House | Ashiya, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1981 |

| Kojima Housing (Sato House) | Okayama Prefecture | Japan | 1981 |

| Atelier in Oyodo | Osaka | Japan | 1981 |

| Tea House for Soseikan-Yamaguchi House | Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1982 |

| Ishii House | Shizuoka Prefecture | Japan | 1982 |

| Akabane House | Setagaya, Tokyo | Japan | 1982 |

| Kujo Townhouse (Izutsu House) | Osaka | Japan | 1982 |

| Rokko Housing One (34°43′32″N 135°13′39″E / 34.725613°N 135.227564°E) | Rokko, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1983 |

| Bigi Atelier | Shibuya, Tokyo | Japan | 1983 |

| Umemiya House | Kobe | Japan | 1983 |

| Kaneko House | Shibuya, Tokyo | Japan | 1983 |

| Festival | Naha, Okinawa prefecture | Japan | 1984 |

| Time's | Kyoto | Japan | 1984 |

| Koshino House Addition | Ashiya, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1984 |

| Melrose, Meguro | Tokyo | Japan | 1984 |

| Uejo House | Osaka Prefecture | Japan | 1984 |

| Ota House | Okayama Prefecture | Japan | 1984 |

| Moteki House | Kobe | Japan | 1984 |

| Shinsaibashi Tokyu Building | Osaka Prefecture | Japan | 1984[18] |

| Iwasa House | Ashiya, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1984 |

| Hata House (34°46′05″N 135°19′26″E / 34.76805°N 135.32397°E) | Nishinomiya, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1984 |

| Atelier Yoshie Inaba | Shibuya, Tokyo | Japan | 1985 |

| Jun Port Island Building | Kobe | Japan | 1985 |

| Mon-petit-chou | Kyoto | Japan | 1985 |

| Guest House for Hattori House | Osaka | Japan | 1985 |

| Taiyō Cement Headquarters Building | Osaka | Japan | 1986 |

| TS Building | Osaka | Japan | 1986 |

| Chapel on Mount Rokko | Kobe | Japan | 1986 |

| Old/New Rokkov | Kobe | Japan | 1986 |

| Kidosaki House | Setagaya, Tokyo | Japan | 1986 |

| Fukuhara Clinic | Setagaya, Tokyo | Japan | 1986 |

| Sasaki House | Minato, Tokyo | Japan | 1986 |

| Main Pavilion for Tennoji Fair | Osaka | Japan | 1987 |

| Karaza Theater | Tokyo | Japan | 1987 |

| Ueda House Addition | Okayama Prefecture | Japan | 1987 |

| Church on the Water | Tomamu, Hokkaido | Japan | 1988 |

| Galleria Akka | Osaka | Japan | 1988 |

| Children's Museum | Himeji, Hyōgo | Japan | 1989 |

| Church of the Light (34°49′08″N 135°22′19″E / 34.818763°N 135.37201°E) | Ibaraki Osaka Prefecture | Japan | 1989[19][20] |

| Collezione | Minato, Tokyo | Japan | 1989 |

| Morozoff P&P Studio | Kobe | Japan | 1989 |

| Raika Headquarters | Osaka | Japan | 1989 |

| Natsukawa Memorial Hall | Hikone, Shiga | Japan | 1989 |

| Yao Clinic, Neyagawa | Osaka Prefecture | Japan | 1989 |

| Matsutani House Addition | Kyoto | Japan | 1990 |

| Ito House, Setagaya | Tokyo | Japan | 1990 |

| Iwasa House Addition | Ashiya, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1990 |

| Garden of Fine Arts | Osaka | Japan | 1990 |

| S Building | Osaka | Japan | 1990 |

| Water Temple (34°32′47″N 134°59′17″E / 34.546406°N 134.98813°E) | Awaji Island, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1991[21] |

| Atelier in Oyodo II | Osaka | Japan | 1991 |

| Time's II | Kyoto | Japan | 1991 |

| Museum of Literature | Himeji, Hyōgo | Japan | 1991 |

| Sayoh Housing | Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1991 |

| Minolta Seminar House | Kobe | Japan | 1991 |

| Benesse House | Naoshima, Kagawa | Japan | 1992[22] |

| Japanese Pavilion for Expo 92 | Seville | Spain | 1992 |

| Otemae Art Center | Nishinomiya, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1992 |

| Forest of Tombs Museum | Kumamoto Prefecture | Japan | 1992 |

| Rokko Housing Two | Rokko, Kobe | Japan | 1993 |

| Vitra Seminar House | Weil am Rhein | Germany | 1993 |

| Gallery Noda | Kobe | Japan | 1993 |

| YKK Seminar House | Chiba Prefecture | Japan | 1993 |

| Suntory Museum | Osaka | Japan | 1994 |

| Maxray Headquarters Building | Osaka | Japan | 1994 |

| Chikatsu Asuka Museum | Osaka Prefecture | Japan | 1994 |

| Kiyo Bank, Sakai Building | Sakai, Osaka | Japan | 1994 |

| Garden of Fine Art | Kyoto | Japan | 1994 |

| Museum of wood culture | Kami, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1994 |

| Inamori Auditorium | Kagoshima | Japan | 1994 |

| Nariwa Museum | Okayama Prefecture | Japan | 1994 |

| Naoshima Contemporary Art Museum | Naoshima, Kagawa | Japan | 1995[23] |

| Atelier in Oyodo Annex | Osaka | Japan | 1995 |

| Nagaragawa Convention Center | Gifu | Japan | 1995 |

| Naoshima Contemporary Art Museum Annex | Naoshima, Kagawa Prefecture | Japan | 1995 |

| Meditation Space, UNESCO | Paris | France | 1995[24] |

| Asahi Beer Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art | Kyoto Prefecture | Japan | 1995[25] |

| Shanghai Pusan Ferry Terminal | Osaka | Japan | 1996 |

| Museum of Literature II, Himeji | Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1996 |

| Gallery Chiisaime (Sawada House) | Nishinomiya, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1996 |

| Museum of Gojo Culture & Annex | Gojo, Nara Prefecture | Japan | 1997 |

| Toto Seminar House | Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1997 |

| Yokogurayama Natural Forest Museum | Kōchi Prefecture | Japan | 1997 |

| Harima Kogen Higashi Primary School & Junior High School | Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1997 |

| Koumi Kogen Museum | Nagano Prefecture | Japan | 1997 |

| Eychaner/Lee House | Chicago, Illinois | United States | 1997 |

| Daikoku Denki Headquarters Building | Aichi Prefecture | Japan | 1998 |

| Daylight Museum | Shiga Prefecture | Japan | 1998 |

| Junichi Watanabe Memorial Hall | Sapporo | Japan | 1998 |

| Asahi Shimbun Okayama Bureau | Okayama | Japan | 1998 |

| Siddhartha Children and Women Hospital | Butwal | Nepal | 1998 |

| Church of the Light Sunday School | Ibaraki, Osaka Prefecture | Japan | 1999 |

| Rokko Housing III' | Kobe | Japan | 1999 |

| Shell Museum, Nishinomiya | Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 1999 |

| Fabrica (Benetton Communication Research Center) | Villorba | Italy | 2000 |

| Awaji-Yumebutai (34°33′40″N 135°00′29″E / 34.560983°N 135.008144°E[26]) | Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 2000 |

| Rockfield Shizuoka Factory | Shizuoka | Japan | 2000 |

| Pulitzer Arts Foundation | St. Louis, Missouri | United States | 2001 |

| Komyo-ji (shrine) | Saijō, Ehime | Japan | 2001 |

| Ryotaro Shiba Memorial Museum | Higashiosaka, Osaka prefecture | Japan | 2001 |

| Osaka Prefectural Sayamaike Museum | Ōsakasayama,Osaka | Japan | 2001 |

| Teatro Armani-Armani World Headquarters | Milan | Italy | 2001 |

| Hyōgo Prefectural Museum of Art | Kobe, Hyōgo Prefecture | Japan | 2002[27] |

| Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth | Fort Worth, Texas | United States | 2002[28] |

| Piccadilly Gardens | Manchester | United Kingdom | 2002; part-demolished 2020.[29] |

| 4x4 house | Kobe | Japan | 2003 |

| Invisible House | Ponzano Veneto | Italy | 2004 |

| Chichu Art Museum | Naoshima, Kagawa | Japan | 2004[30] |

| Langen Foundation | Neuss | Germany | 2004[31] |

| Gunma Insect World Insect Observation Hall | Kiryū, Gunma | Japan | 2005 |

| Picture Book Museum | Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture | Japan | 2005[32] |

| Saka no Ue no Kumo Museum | Matsuyama, Ehime | Japan | 2006 |

| Morimoto (restaurant) | Chelsea Market, Manhattan | United States | 2005 |

| Sakura Garden | Osaka | Japan | 2006 |

| Omotesando Hills, Jingumae 4-Chome | Tokyo | Japan | 2006 |

| House in Shiga | Ōtsu, Shiga | Japan | 2006 |

| 21 21 Design Sight | Minato, Tokyo | Japan | 2007 |

| Stone Hill Center expansion for the Clark Art Institute | Williamstown, Massachusetts | United States | 2008[33] |

| Glass House | Seopjikoji | South Korea | 2008[34] |

| Genius Loci | Seopjikoji | South Korea | 2008[34] |

| Punta della Dogana (restoration) | Venice | Italy | 2009[35] |

| House, stable, and mausoleum for fashion designer and film director Tom Ford's Cerro Pelon Ranch | near Santa Fe, New Mexico | United States | 2009 |

| Rebuilding the Kobe Kaisei Hospital | Nada Ward, Kobe | Japan | 2009 |

| Gate of Creation, Universidad de Monterrey | Monterrey | Mexico | 2009 |

| NIWAKA Building | Kyoto | Japan | 2009[36] |

| Capella Niseko Resort and Residences | Niseko, Abuta District, Shiribeshi, Hokkaido Prefecture | Japan | 2010 |

| Interior design of Miklós Ybl Villa | Budapest | Hungary | 2010 |

| Kaminoge Station, Tokyu Corporation | Tokyo | Japan | 2011 |

| Centro Roberto Garza Sada of Art Architecture and Design | Monterrey | Mexico | 2012 |

| Akita Museum of Art | Akita, Akita | Japan | 2012 |

| Bonte Museum | Seogwipo | South Korea | 2012[34] |

| Asia Museum of Modern Art | Wufeng, Taichung | Taiwan | 2013 |

| Hansol Museum[37] (Museum SAN) | Wonju | South Korea | 2013 |

| Aurora Museum | Shanghai | China | 2013 |

| Richard Sachs Residence[38][39] | Malibu | United States | 2013 |

| Visitor, Exhibition and Conference Center, Clark Art Institute | Williamstown, Massachusetts | United States | 2014 |

| Casa Wabi | Puerto Escondido, Oax | Mexico | 2014[40] |

| JCC (Jaeneung Culture Center) | Seoul | South Korea | 2015[41] |

| Hill of the Buddha | Sapporo | Japan | 2015 |

| Setouchi Aonagi | Matsuyama, Ehime | Japan | 2015 |

| 27712 Pacific Coast Highway | Malibu, California | United States | 2015 |

| Pearl Art Museum | Shanghai | China | 2017 |

| 152 Elizabeth Street Condominiums | New York, New York | United States | 2018 |

| Wrightwood 659 | Chicago | United States | 2018[42] |

| Nakanoshima Children's Book Forest | Osaka | Japan | 2020[43] |

| LG Arts Center SEOUL | Seoul | South Korea | 2022[44] |

| Realm of the Light | New Taipei City | Taiwan | 2023 |

| MPavilion | Melbourne, Australia | Australia | 2023 |

- Works and details of different works by Tadao Ando

Asahi Beer Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art, Kyoto

Asahi Beer Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art, Kyoto Lincoln park house, Chicago

Lincoln park house, Chicago Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, showing the reflecting pool

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, showing the reflecting pool Himeji City Museum of Literature

Himeji City Museum of Literature Azuma House

Azuma House View from Akita Museum of Art

View from Akita Museum of Art Mount Rokko Chapel

Mount Rokko Chapel Suntory Museum, showing the staircase and the inside structure

Suntory Museum, showing the staircase and the inside structure City Museum of Literature

City Museum of Literature Chikatsu Asuka museum

Chikatsu Asuka museum Awaji Yumebutai in Awaji, Hyogo prefecture, Japan

Awaji Yumebutai in Awaji, Hyogo prefecture, Japan Awaji Yumebutai, showing the view and the stairs down

Awaji Yumebutai, showing the view and the stairs down Suntory Museum, the parallelepiped intersecting the spherical body of the IMAX theatre, shown in profile

Suntory Museum, the parallelepiped intersecting the spherical body of the IMAX theatre, shown in profile Rokko Housing I and II, Kobe

Rokko Housing I and II, Kobe Vitra Conference Pavillon

Vitra Conference Pavillon Langen Foundation at night

Langen Foundation at night Osaka Prefectural Sayamaike Museum

Osaka Prefectural Sayamaike Museum

LungYen Realm of the Light Service Center at night

LungYen Realm of the Light Service Center at night

Awards

References

- ↑ "Tadao Ando - Great Buildings Online". www.greatbuildings.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- 1 2 "Biography: Tadao Ando". The Pritzker Architecture Prize. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- 1 2 "Tadao Ando". Encyclopedia of World Biography. Advameg, Inc. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ↑ 헤럴드경제 (2012-08-29). "일본의 건축 거장 안도 다다오..."늘 도전하고 스스로 깨뜨려라"" (in Korean). Archived from the original on 2017-10-16. Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ↑ Makiko Kitamura (September 29, 2009), Bono’s Home Designer Ando Plans Art Center at Provence Winery Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine Bloomberg.

- ↑ "Tadao Ando". Yatzer. 2016-11-08. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ↑ Masao Furuyama. “Tadao Ando”. Taschen, 2006. ISBN 978-3-8228-4895-1.

- ↑ Werner Blaser, Tadao Ando, Architecktur der Stille, Architecture of Silence Birkhäuser, 2001. ISBN 3-7643-6448-3.

- ↑ Goldberger, Paul (1995-04-23). "ARCHITECTURE VIEW; 'Laureate' in a Land of Zen and Microchips". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ↑ Jin Baek. (2009). Nothingness : Tadao Ando's Christian Sacred Space. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-282-15316-5. OCLC 742294296.

- ↑ Jin Baek, Nothingness: Tadao Ando’s Christian Sacred Space. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 978-0-415-47854-0.

- ↑ "Tadao Ando Builds With Nature In Mind". Christian Science Monitor. 1994-02-18. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ↑ Allen, Eric (23 July 2016). "13 Examples of Modern Architecture by Tadao Ando". Architectural Digest. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ↑ Muschamp, Herbert. (1995). "Among the Fountains with Tadao Ando; Concrete Dreams In the Sun King's Court," New York Times. September 21, 1995.

- ↑ Brandon, Elissaveta M. (23 October 2019). "50 Years of Japan's Changing Architectural Landscape". Architectural Digest. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- 1 2 Goldberger, Paul. "Architecture View: 'Laureate' in a Land of Zen and Microchips," The New York Times. April 23, 1995.

- ↑ Bassin, Joan. "Frank Lloyd Wright's Imperial Hotel" Archived 2007-10-19 at the Wayback Machine, National Building Museum exhibition.

- ↑ Nobi, Sacré (25 October 2006). "An Encounter". What We Do Is Secret. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- ↑ "The Church of Light - Tadao Ando". 25 November 2001. Archived from the original on 8 April 2007. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- ↑ Michelle Chan (2000-02-23). "Church of the Light - Tadao Ando". Arch.mcgill.ca. Archived from the original on 2015-09-09. Retrieved 2014-01-03.

- ↑ Floornature - architectural news, design and information resource for ceramic tile and stone Archived 2004-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Williams, Ingrid K (26 August 2011). "Japanese Island as Unlikely Arts Installation". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ "ベネッセアートサイト直島". ベネッセアートサイト直島. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ↑ Furuyama, Masao. "Ando (Basic Art Series)". www.taschen.com. pp. 71–72. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- ↑ "Asahi Beer Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art". Asahibeer-oyamazaki.com. 2013-12-26. Archived from the original on 2014-01-03. Retrieved 2014-01-03.

- ↑ "Wikimapia - Let's describe the whole world!". wikimapia.org. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ↑ "Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art". Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art_Architectural Overview. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ↑ Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth Archived 2004-08-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "C20 condemns the demolition of Tadao Ando's wall in Manchester". Twentieth Century Society. 17 November 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ↑ Chichu Art Museum Archived 2005-04-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Langen Foundation". Langenfoundation.de. Archived from the original on 2013-01-24. Retrieved 2014-01-03.

- ↑ "Works 安藤忠雄 Tadao Ando". Tadao-ando.com. Archived from the original on 2014-01-28. Retrieved 2014-01-03.

- ↑ "Clark Art Institute". Andotadao.org. 2009-03-14. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2014-01-03.

- 1 2 3 Shim, Youngkyu (19 November 2013). "Here, Now, Ando Tadao". Space Magazine. Seoul. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ↑ "Arte contemporanea | Palazzo Grassi" (in Italian). Palazzograssi.it. 2013-12-18. Archived from the original on 2014-01-11. Retrieved 2014-01-03.

- ↑ "NIWAKA Kyoto flagship store / Tadao Ando: TATEMOG". kenchiqoo.net. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ↑ Woo-young, Lee (16 May 2013). "Nature and art become one at Hansol Museum". The Korea Herald. Seoul. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ↑ Katherine Clarke (February 24, 2020), In Malibu, A Concrete Compound Designed By Japanese Starchitect Asks $75 Million Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ James McClain (September 21, 2021), Kanye West Buys Tadao Ando-Designed Malibu House ARTnews.

- ↑ "Acerca de..About". casawabi. Archived from the original on 2017-04-10. Retrieved 2017-04-09.

- ↑ "Insight Trip_Jaeneung Culture Center and Naksan Park". webzine.etri.re.kr. Archived from the original on 2017-09-28. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- ↑ "Inside Wrightwood 659, a New Home for Art and Architecture". WTTW News. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- ↑ "Nakanoshima Children's Book Forest". Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ↑ "LG Arts Center Seoul to reopen in western Seoul this week". Yonhap News Agency. October 12, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ↑ "ENV college awards architect Tadao Ando". The Poly Post. Archived from the original on 2012-05-09. Retrieved 2017-09-29.

- ↑ web, Segretariato generale della Presidenza della Repubblica-Servizio sistemi informatici- reparto. "Le onorificenze della Repubblica Italiana". Quirinale. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ↑ Ambafrance

- ↑ Ambafrance

Literature

- Francesco Dal Co. Tadao Ando: Complete Works. Phaidon Press, 1997. ISBN 0-7148-3717-2

- Kenneth Frampton. Tadao Ando: Buildings, Projects, Writings. Rizzoli International Publications, 1984. ISBN 0-8478-0547-6

- Randall J. Van Vynckt. International Dictionary of Architects and Architecture. St. James Press, 1993. ISBN 1-55862-087-7

- Masao Furuyama. “Tadao Ando”. Taschen, 2006. ISBN 978-3-8228-4895-1

- Werner Blaser, “Tadao Ando, Architecktur der Stille, Architecture of silence” Birkhäuser, 2001. ISBN 3-7643-6448-3

- Jin Baek, “Nothingness: Tadao Ando’s Christian Sacred Space”. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 978-0-415-47854-0