| Citadel of Aleppo | |

|---|---|

قلعة حلب | |

| Aleppo, Syria | |

The Citadel of Aleppo in 2010 | |

Citadel of Aleppo | |

| Coordinates | 36°11′57″N 37°09′45″E / 36.19917°N 37.16250°E |

| Type | Castle/Citadel |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Government of Syria |

| Controlled by | |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Partially ruined (some parts repaired and destroyed) |

| Site history | |

| Built | 3rd millennium BC – 12th century AD |

| In use | Until 21st century |

| Materials | Limestone |

| Battles/wars | Syrian Civil War |

.jpg.webp)

The Citadel of Aleppo (Arabic: قلعة حلب, romanized: Qalʿat Ḥalab) is a large medieval fortified palace in the centre of the old city of Aleppo, northern Syria. It is considered to be one of the oldest and largest castles in the world. Usage of the Citadel hill dates back at least to the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. Occupied by many civilizations over time – including the Greeks, Armenians, Romans, Byzantines, Ayyubids, Mamluks and Ottomans – the majority of the construction as it stands today is thought to originate from the Ayyubid period. An extensive conservation work took place in the 2000s by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, in collaboration with Aleppo Archeological Society. Dominating the city, the Citadel is part of the Ancient City of Aleppo, an UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1986.[1] During the 2010s, the Citadel received significant damage during the lengthy Battle of Aleppo.[2][3] It was reopened to the public in early 2018 with repairs to damaged parts underway, though some of the damage will be purposefully preserved as part of the history of the citadel.[4] The citadel was damaged by the 2023 Turkey–Syria earthquake.

History

The recently discovered temple of the ancient storm-god Hadad dates use of the hill to the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, as referenced in cuneiform texts from Ebla and Mari.[5] The city became the capital of Yamhad and was known as the "City of Hadad".[6] The temple remained in use from the 24th century BC[7] to at least the 9th century BC,[8] as evidenced by reliefs discovered at it during excavations by German archaeologist Kay Kohlmeyer.

The patriarch Abraham is said to have milked his sheep on the citadel hill.[9] After the decline of the Neo-Hittite state centered in Aleppo, the Assyrians dominated the area (8th–4th century BC), followed by the Neo-Babylonians and the Persians (539–333).[10]

Seleucid period

After Aleppo was taken by the armies of Alexander the Great, Aleppo was ruled by Seleucus I Nicator, who undertook the revival of the city under the name Beroia. Medieval Arab historians say that the history of the citadel as a fortified acropolis began under Nicator.[9] In some areas of the citadel there are up to two meters of remains of Hellenistic settlement. A colonnaded street led up to the citadel hill from the west, where the south area of Aleppo still retains the Hellenistic grid street plan.[11]

Roman and Byzantine periods

After the Romans deposed the Seleucid dynasty in 64 BC, the citadel hill continued to have religious significance. Emperor Julian, in his 363 AD visit to Aleppo noted "I stayed there for a day, visited the acropolis, offered a white bull to Zeus according to imperial customs, and held a short talk with the town council about worshiping the gods." Very few physical remains have been found from the Roman age in the Citadel.[10]

The Roman Empire was divided into two parts in 395. Aleppo was in the eastern half, Byzantium. During the clashes with the Sassanian king Khosrau II in the 7th century, the population of Aleppo is said to have taken refuge in the Citadel because the city wall was in a deplorable state. Currently, very few remains from the Byzantine period have been found on the Citadel Hill, although the two mosques inside the Citadel are known to be converted from churches originally built by the Byzantines.[9][10]

Early Islamic period

Muslim troops captured Aleppo in 636 AD. Written sources document repairs being made on the citadel after a major earthquake. Little is known about the citadel in the period of early Islam, except that Aleppo was a frontier town on the edges of the Ummayad and Abbasid empires.[10]

Sayf al-Dawla, a Hamdanid prince, conquered the city in 944, and it subsequently rose to a political and economic renaissance.[10][12] The Hamdanids built a reputedly splendid palace on the banks of the river, but moved to the Citadel after Byzantine troops attacked in 962. A period of instability followed Hamdanid rule, marked by Byzantine and Beduin attacks, as well as a short-term rule by the Egyptian-based Fatimids. The Mirdasids were said to have converted the two churches into mosques.[10]

Zengid and Ayyubid periods

The citadel rose to the peak of its importance in the period during and after the Crusader presence in the Near East. Zengid ruler Imad ad-Din Zengi – followed by his son Nur ad-Din (ruled 1147–1174) – successfully unified Aleppo and Damascus and held back the Crusaders from their repeated assaults on the cities. Several famous crusaders were imprisoned in the citadel, among them Count of Edessa, Joscelin II, who died there, Raynald of Châtillon, and the King of Jerusalem, Baldwin II, who was held for two years. In addition to his many works in both Aleppo and Damascus, Nur ad-Din rebuilt the Aleppo city walls and fortified the citadel. Arab sources report that he also made several other improvements, such as a high, brick-walled entrance ramp, a palace, and a racecourse likely covered with grass. Nur ad-Din additionally restored or rebuilt the two mosques and donated an elaborate wooden mihrab (prayer niche) to the Mosque of Abraham. The mihrab disappeared during the French Mandate.[13]

Saladin's son, al-Zahir al-Ghazi, ruled Aleppo between 1193 and 1215. During this time, the citadel went through major reconstruction, fortification and addition of new structures that create the complex of the Citadel in its current form today. Sultan Ghazi strengthened the walls, smoothed the surface of the outcrop and covered sections of the slope at the entrance area with stone cladding. The depth of the moat was increased, connected with water canals and spanned by a tall bridge-cum-viaduct, which today still serves as the entrance into the Citadel. During the first decade of the 13th century the citadel evolved into a palatial city that included functions ranging from residential (palaces and baths), religious (mosque and shrines), military installations (arsenal, training ground, defence towers and the entrance block) and supporting elements (water cisterns and granaries). The most prominent renovation is the entrance block rebuilt in 1213. Sultan Ghazi also had the two mosques on the Citadel restored, and expanded the city walls to include the southern and eastern suburbs, making the citadel the centre of the fortifications, rather than alongside the wall.[13]

Mongol and Mamluk periods

The citadel was damaged by the Mongol invasion of 1260 and again destroyed by the invasion led by the Turco-Mongol leader Timur which swept through Aleppo in 1400–1401.[13]

In 1415 the Mamluk governor of Aleppo, prince Sayf al-Din, was authorized to rebuild the citadel, which by then stood at the centre of a significant trading city of between 50,000–100,000 inhabitants.[14] Sayf al-Din's additions included two new advance towers on the north and south slopes of the citadel, and the new Mamluk palace built on top of the higher of the two entrance towers. The Ayyubid palace was almost completely abandoned during this period. The Mamluk period also administered restoration and preservation projects on the Citadel. The final Mamluk sultan, al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghawri, replaced the flat ceiling of the Throne Hall with nine domes.[15]

Ottoman period

During the Ottoman period, the military role of the citadel as a defense fortress slowly diminished as the city began to grow outside the city walls and was taking its form as a commercial metropolis. The Citadel was still used as a barracks for Ottoman soldiers, although it is not known exactly how many were stationed there. An anonymous Venetian traveler mentions some 2,000 people living in the Citadel in 1556. In 1679, the French consul d’Arvieux reports 1,400 people there, 350 of whom were Janissaries, the elite military corps in the service of the Ottoman Empire. Sultan Süleyman ordered a restoration of the citadel in 1521.[9][16]

Aleppo and the citadel were heavily damaged in the earthquake of 1822. After the earthquake only soldiers lived in the citadel.[9] The Ottoman Governor of the time, Ibrahim Pasha, used stones from destroyed buildings in the citadel to build a barracks in the north of the crown. It was later restored under the rule of Sultan Abdülmecid in 1850–51. A windmill, also on the northern edge of the crown, was probably built around the same time.[16]

French Mandate

Soldiers continued to be stationed in the citadel during the French Mandate (1920–45). The French began archaeological excavations and extensive restoration work in the 1930s, particularly on the perimeter wall. The Mamluk Throne Hall was also completely restored during this time and given a new flat roof decorated in 19th-century Damascene style. A modern amphitheater was constructed on a section of an unexcavated surface of the citadel in 1980 to hold events and concerts.[17]

Modern day

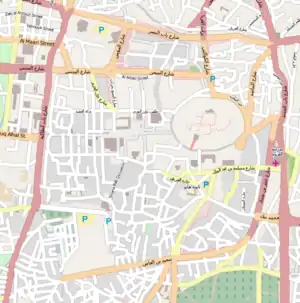

The citadel in its present form is on a mound, which has an elliptical base with a length of 450 metres (1,480 feet) and width of 325 metres (1,066 feet). At the top this ellipse measures 285 metres (935 feet) by 160 metres (520 feet) with the height of this slanting foundation measuring 50 metres (160 feet). In the past, the entire mound was covered with large blocks of gleaming limestone, some of which still remain today.[17]

The mound is surrounded by a 22-metre-deep (72-foot) and 30-metre-wide (98-foot) moat, dating from the 12th century. Notable is the fortified gateway, accessible though an arched bridge. This feature was an addition from the Mamluk government in the 16th century. A succession of five right-angle turns and three large gates (with carved figures) leads to the main inner castle entrance.[17] In the interior of the Citadel, are the Weapons' Hall, the Byzantine Hall and the Throne Hall, with a restored decorated ceiling. Prior to the Syrian civil war, the citadel was a tourist attraction and a site of archaeological digs and studies. The amphitheater was often used for musical concerts or cultural events.[17]

In August 2012, during the Battle of Aleppo of the Syrian Civil War, the external gate of the citadel was damaged after being shelled during a clash between the Free Syrian Army and the Syrian Army to gain control over the citadel.[18] In July 2015, a bomb was set off in a tunnel under one of the outer walls causing further damage to the citadel, in an attempt for the Free Syrian Army to dislodge the Syrian Army.[19] During the conflict, the Syrian Army used the Citadel as a military base, and according to the opposition fighters, with the walls acting as cover while shelling surrounding areas and ancient arrow slits in walls being used by snipers to target rebels.[20] As a result of this contemporary usage, the Citadel has received significant damage.[2][3][21]

The citadel was extensively damaged by the magnitude 7.8 2023 Turkey–Syria earthquake on February 6, 2023.[22]

Internal sites

There are many structural remains inside the citadel. Notable sites include:

Entrance block

The enormous stone bridge constructed by Sultan Ghazi over the moat led to an imposing bent entrance complex. Would-be assailants to the castle would have to take over six turns up a vaulted entrance ramp, over which were machicolations for pouring hot liquids on attackers from the mezzanine above. Secret passageways wind through the complex, and the main passages are decorated with figurative reliefs. The Ayyubid block is topped by the Mamluk "Throne Hall", a hall where Mamluk sultans entertained large audiences and held official functions.[23]

Ayyubid Palace and Hammam

Ghazi's "palace of glory" burned down on his wedding night, but it was later rebuilt and today stands as one of the most important and impressive monuments in the citadel crown. The Ayyubids were not the first to build a palace on the citadel. Today, numerous architectural details remain from the Ayyubid period, including an entrance portal with muqarnas, or honeycomb vaulting, and a courtyard on the four-iwan layout, with tiling.[24]

Laid out in traditional medieval Islamic style, the palace hammam has three sections. The first was used for dressing, undressing, and resting. The second was an unheated but warmer room, and this was followed by a hot room, and a steam room equipped with alcoves. Hot and cold water was piped through to the hammam with earthenware pipes.[24]

Satura, Hellenistic Well, and underground passages

The construction in the citadel was not confined to above-ground. Several wells penetrate down to 125 m (410 ft) below the surface of the crown. Underground passageways connect to the advance towers and possibly under the moat to the city.[24]

References

- ↑ "Ancient City of Aleppo". UNESCO. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved Mar 7, 2012.

- 1 2 @edwardedark (July 29, 2014). "Video: rebels blow up historic building in front of Aleppo citadel today" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- 1 2 "Syrian heritage destruction revealed in satellite images". BBC News. September 19, 2014. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Aleppo Citadel reopens its doors as thousands of visitors regain their memories in". SANA. 16 June 2018. Archived from the original on 18 January 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ↑ DayPress News, "Temple of Hadad in Aleppo Citadel Sheds Light on Important Periods" Archived 2020-05-07 at the Wayback Machine, Jan 16, 2010.

- ↑ Lluís Feliu (January 2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. BRILL. p. 192. ISBN 9004131582.

- ↑ Hugh N. Kennedy (2006). Muslim Military Architecture in Greater Syria. BRILL. p. 166. ISBN 9004147136.

- ↑ Gülru Necipoğlu,Karen Leal (11 November 2010). Muqarnas. BRILL. p. 114. ISBN 978-9004185111.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bianca and Gaube, 2007, pp. 73–103

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gonnela, 2008, pp. 12–13

- ↑ Gonnela, 2008, p.11

- ↑ Burns, Ross, Monuments of Syria; An Historical Guide, London: Tauris

- 1 2 3 Gonnela, 2008, pp. 14–19

- ↑ Hourani, A. (1992). A History of the Arab Peoples. New York: Warner. ISBN 9780446393928.

- ↑ Gonnela, 2008, pp. 19–20

- 1 2 Gonnela, 2008, pp. 21–24

- 1 2 3 4 Gonnela, 2008, p.25

- ↑ "Aleppo citadel hit by shelling, says opposition". The Daily Star Lebanon. Agence France Presse. 11 August 2012. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ↑ "Syria civil war: Bomb damages Aleppo's ancient citadel". BBC News. July 12, 2015. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ↑ Abigail Hauslohner and Ahmed Ramadan (5 May 2013). "Ancient Syrian castles serve again as fighting positions". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ↑ UNESCO [49267] (2017). "Five years of conflict: the state of cultural heritage in the Ancient City of Aleppo; A comprehensive multi-temporal satellite imagery-based damage analysis for the Ancient City of Aleppo". unesdoc.unesco.org. pp. 34–56. Archived from the original on 2019-07-22. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "آثار سوريا لم تسلم من الزلزال.. تضرر قلعتي حلب والمرقب" (in Arabic). Al Arabiya. 6 February 2023. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ↑ Gonnela, 2008, pp. 31 35

- 1 2 3 Gonnela, 2008, pp. 46 48

Sources

- Julia Gonella, Wahid Khayyata, Kay Kohlmeyer: Die Zitadelle von Aleppo und der Tempel des Wettergottes. Rhema-Verlag, Münster 2005, ISBN 978-3-930454-44-0.

- Gonnella, Julia (2008), The Citadel of Aleppo: Description, History, Site Plan and Visitor Tour (Guidebook), Aga Khan Trust for Culture and the Syrian Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums, ISBN 978-2-940212-02-6, archived from the original on 2012-06-09.

- Bianca, Stefano (2007), Syria: Medieval Citadels Between East and West, Aga Khan Trust for Culture, ISBN 978-2-940212-02-6, archived from the original on 2011-06-04, retrieved 2009-07-24.

External links

- Syrian Ministry of Tourism Archived 2019-11-16 at the Wayback Machine, Arabic section

- Historic Cities Support Programme, Aga Khan Trust for Culture

- Extensive photo site about the citadel