| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

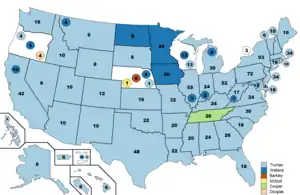

All 1,176 delegate votes of the Democratic National Convention 589 delegate votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Senator from Missouri

33rd President of the United States

First term Second term Presidential and Vice presidential campaigns Post-presidency

|

||

The Democratic Party's 1944 nomination for Vice President of the United States was determined at the 1944 Democratic National Convention, on July 21, 1944. U.S. Senator Harry S. Truman from Missouri was nominated to be President Franklin D. Roosevelt's running-mate in his bid to be re-elected for a fourth term.

How the nomination went to Truman, who did not actively seek it, is, in the words of his biographer Robert H. Ferrell, "one of the great political stories of our century".[1] The fundamental issue was that Roosevelt's health was seriously declining, and everyone who saw Roosevelt, including the leaders of the Democratic Party, realized it. If he died during his next term, the vice president would become president, making the vice presidential nomination very important. Truman's predecessor as vice president, the incumbent Henry A. Wallace, was unpopular with some of the leaders of the Democratic Party, who disliked his liberal politics and considered him unreliable and eccentric in general. Wallace was the popular candidate and favored by the Convention delegates.

As the Convention began, Wallace had more than half the votes necessary to secure his re-nomination.[2] By contrast, the Gallup poll said that 2% of those surveyed wanted then-Senator Truman to become the vice president.[3] To overcome this initial deficit, the leaders of the Democratic Party worked to influence the Convention delegates, such that Truman received the nomination.[4]

Anti-Wallace movement

A powerful group of party leaders tried to persuade Roosevelt to not keep Wallace as vice president. Ferrell calls this process "a veritable conspiracy".[4] The group consisted of Edwin W. Pauley, treasurer of the Democratic National Committee (DNC); Robert E. Hannegan, Democratic national chairman; Frank C. Walker, Postmaster General; George E. Allen, the Democratic party secretary; and Edward J. Flynn, political boss of New York. They considered several people to replace Wallace. Among the possible candidates were James F. Byrnes, Roosevelt's "assisting president", who initially was the prominent alternative, Associate Justice William O. Douglas, U.S. Senators Alben W. Barkley and Harry S. Truman as well as the industrialist Henry J. Kaiser and Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn.[5] Finally the group decided on Truman, but this decision was secondary to the goal of not nominating Wallace.[6] By late spring 1944, the group had succeeded in turning Roosevelt against Wallace, but the president did not tell Wallace directly and still refused to endorse anybody other than him.[7] In May, the president sent Wallace on a trip to China and the Soviet Union, probably with the intention to get him out of the country at an inconvenient time and to obstruct his campaign.[8]

Roosevelt preferred Byrnes as the best alternative and decided to push him as the party's nominee for the vice presidency if the party delegates refused to renominate Wallace at the 1944 Democratic National Convention.[7] On July 11, the leaders met with Roosevelt in the White House. They recommended Truman. The names of Rayburn, Barkley, Byrnes, and John G. Winant were also raised, but they were dismissed, Byrnes because of his unpopularity among blacks and in the labor movement.[9] Furthermore, Byrnes, who had been born a Roman Catholic, had left the church to become an Episcopalian, which would have alienated many Catholic voters who were a central part of the New Deal coalition.[10] Truman was an ideal compromise candidate. He supported the administration on most issues, was acceptable to the unions, and he had opposed Roosevelt's reelection to a third term, which pleased conservative anti-Roosevelt Democrats. He had supported Roosevelt's foreign policy but was close to Senate isolationists like Burton K. Wheeler.[11] Roosevelt did not know Truman well, but he knew of the senator's leadership of the Truman Committee, and that he was a loyal supporter of the New Deal. Roosevelt suggested William O. Douglas but party officials countered by suggesting Truman.[7]

After much debate, the president said, "Bob [Hannegan], I think you and everyone else here want Truman."[12] There are, however, other accounts of Roosevelt's exact statement. Pauley, for example, claimed that he said, "If that's the case, it's Truman."[13] Just before the meeting ended, Roosevelt instructed Hannegan and Walker to notify Wallace and Byrnes, respectively, that they were out.[14] After the group left the meeting, Hannegan asked Roosevelt to put his decision down in writing. Roosevelt wrote a note on a piece of scratch paper and gave it to Hannegan.

The next day Hannegan and Walker thus tried to convince Wallace and Byrnes to withdraw, but they refused unless the president himself asked them. Roosevelt did not want to disappoint any candidate.[7] He told Wallace, "I hope it will be the same old team." But Wallace nevertheless understood the president's real intentions, and he wrote in his diary, "He wanted to ditch me as noiselessly as possible." Roosevelt also promised to write a letter, saying that if he, Roosevelt, were a delegate to the convention he would vote for Wallace.[7] To Byrnes Roosevelt said, "You are the best qualified man in the whole outfit and you must not get out of the race.[7] If you stay in the race you are certain to win." He also explained to Byrnes that he was having trouble with Wallace, who refused to withdraw unless the president told him so, and that he would write Wallace a lukewarm letter.[15]

Maneuvering

On July 15, Roosevelt was en route to San Diego. He stopped in Chicago, where the Democratic national convention was to be held. Hannegan and Edward J. Kelly, mayor of Chicago, met Roosevelt on board the train. They obtained a typewritten version of the note from July 11:[7]

Dear Bob:

You have written me about Harry Truman and Bill Douglas. I should, of course, be very glad to run with either of them and believe that either one of them would bring real strength to the ticket.

- Always Sincerely,

- Franklin D. Roosevelt

Grace Tully, the president's private secretary, asserted in her memoirs that the letter as originally written put Douglas's name first, but Hannegan asked her to switch the position of the names so it would appear as if Roosevelt preferred Truman. Hannegan, however, has denied this.[16] Truman biographer Conrad Black wrote that Tully did switch the positions of the names, but it was probably at Roosevelt's wish.[17] Truman later claimed that Hannegan had shown him a letter from Roosevelt that did not mention Douglas's name, saying "Bob, it's Truman. FDR." This letter has never been found.[18]

A photograph of FDR's original letter appears in a biography of Douglas.[19]

Hannegan also tried to get Roosevelt to tone down the Wallace letter. The situation became even more complicated because Roosevelt said pleasant things about Byrnes, so Hannegan believed the president had changed his mind and wanted Byrnes. However, Roosevelt also said that Hannegan must clear Byrnes' nomination with labor leader Sidney Hillman, whom he knew opposed Byrnes.[20] The line "Clear it with Sidney" was subsequently used by Thomas Dewey and the Republicans in their campaign.[21]

On July 17, the chairman of the convention, Samuel D. Jackson, released Roosevelt's Wallace letter. Roosevelt said, somewhat ambiguously, that he, if a delegate, would vote for Wallace, but that he did not want to dictate to the convention. Because it was a lukewarm endorsement, the letter became known as the "kiss-of-death" letter among the Byrnes and Truman supporters, but on the other hand, as some people pointed out, Wallace was the only candidate who had received a written endorsement. Hannegan had not told anyone about the letter he received on July 15, but now he said that he had a letter in which the president mentioned Truman.[22]

On July 16 and 17, Sunday and Monday, Byrnes had several setbacks. One was Flynn's concern about losing black votes in case Byrnes got the nomination. The other, more serious, was the increasing opposition against Byrnes from labor, in particular Hillman.[23] On Monday evening the party leaders telephoned Roosevelt, saying that labor would not accept Byrnes and mentioned Flynn's concern as well.[24] Roosevelt concurred and told them to "go all out for Truman". Now, when the president had really decided on Truman, the leader's next step was to convince Truman that he was Roosevelt's pick.[25] They let Byrnes's friend Leo Crowley inform Byrnes. Truman probably learned of Roosevelt's endorsement the same evening, but he was aware of the president's inconsistency and could not be sure of what it meant. Truman had previously, just like Hannegan, got the impression that Roosevelt wanted Byrnes. But the next morning Truman met with Hillman, who refused to accept Byrnes and said that labor's first choice was Wallace, and if that was impossible they could also consent to Truman or Douglas. Roosevelt had met Hillman the previous Thursday. There is no proof that Roosevelt conspired and struck a deal with Hillman not to accept Byrnes, but it might very well have been like that, according to Ferrell. Byrnes believed that Roosevelt had betrayed him.[26][27]

Only now, after his meeting with Hillman, did Truman know that he had a good chance to be nominated[28] although Truman had planned to nominate Byrnes, and had the text of a nomination speech for him in his pocket.[27] Truman had repeatedly said that he was not in the race and that he did not want to be vice president, and he remained reluctant.[29] One reason was that he had put his wife Bess on his Senate office payroll and he didn't want her name "drug over the front pages of the papers". Since 1943 he also had his sister Mary Jane on the payroll. Moreover, Bess disliked Roosevelt and the White House in general. Byrnes, who was disappointed with Roosevelt, withdrew on Wednesday, July 19, "in deference to the wishes of the president."[30]

On Wednesday, Truman and the leaders gathered in Hannegan's suite in Blackstone Hotel. Hannegan called Roosevelt while Truman listened, and told him that Truman was a contrary Missouri mule. Roosevelt replied loudly, so everyone in the room could hear, "Well, tell him if he wants to break up the Democratic Party in the middle of a war, that's his responsibility," and slammed down the receiver. Truman was dumbstruck, but after a few moments replied, "Well, if that is the situation, I'll have to say yes. But why the hell didn't he tell me in the first place?" By another account he just said, "Jesus Christ." Before the call, Hannegan and Roosevelt had agreed what each one should say.[31]

On Thursday, July 20, Hannegan released the letter which Roosevelt had given him on board the train, and its text appeared in the newspapers the next morning, but as it mentioned both Truman and Douglas it made people confused. The ballot was also held on Thursday. Wallace supporters had packed the convention hall and tried to stampede the convention, as Wendell Willkie had successfully done at the Republican convention four years earlier for the presidential nomination. There were parades and chants for Wallace, and banners for him were everywhere. The organist played the Iowa song, "Iowa, Iowa, that's where the tall corn grows!" Entrance tickets for each day to the Chicago Stadium had been printed in the same color, and probably the Wallace supporters used all their tickets for the Thursday, and the ushers and takers at the gates couldn't see the difference. It is also possible that they counterfeited the tickets.[32] To avoid a victory for Wallace, the leaders got the organist to change his tune and they had Jackson, a Wallace supporter, recognize Mayor David L. Lawrence of Pittsburgh, who moved an adjournment until the next morning.[33]

Until the next day, according to Truman biographer David McCullough, the leaders tried to convince the delegates to vote for Truman. He writes in his book Truman: "But Hannegan, Flynn, Kelly, and the others had been working through the night, talking to delegates and applying 'a good deal of pressure' to help them see the sense in selecting Harry Truman. No one knows how many deals were cut, how many ambassadorships or postmaster jobs were promised, but reportedly, by the time morning came, Postmaster General Frank Walker had telephoned every chairman of every delegation." But Robert Ferrell states that their tactics were not to make deals with delegates during the night, but to talk to the delegates during Friday and tell them the president wanted Truman.[34] Meanwhile, police kept large numbers of Wallace supporters out of the convention venue.[35]

Vote

At the presidential balloting, Roosevelt got an overwhelming majority, 1086 votes, far ahead of Harry F. Byrd with 89 votes and James A. Farley with one vote.

| Vice Presidential Balloting | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | 1st | 2nd (Before Shifts) | 2nd (After Shifts) |

| Truman | 319.5 | 477.5 | 1,031 |

| Wallace | 429.5 | 473 | 105 |

| Bankhead II | 98 | 23.5 | 0 |

| Lucas | 61 | 58 | 0 |

| Barkley | 49.5 | 40 | 6 |

| Broughton | 43 | 30 | 0 |

| McNutt | 31 | 28 | 1 |

| O'Mahoney | 27 | 8 | 0 |

| Cooper | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| Kerr | 23 | 1 | 0 |

| O'Conor | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| Thomas | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Douglas | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Pepper | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Murphy | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Rayburn | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Timmons | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Not Voting | 29.5 | 4 | 0 |

| Absent | 3 | 3 | 3 |

- Balloting for the Vice Presidential nomination at the 1944 Democratic National Convention

1st Vice Presidential Ballot

1st Vice Presidential Ballot 2nd Vice Presidential Ballot (Before Shifts)

2nd Vice Presidential Ballot (Before Shifts) 2nd Vice Presidential Ballot (After Shifts)

2nd Vice Presidential Ballot (After Shifts)

Analysis and aftermath

Both Ferrell and McCullough compare the way Truman was nominated with more recent presidential elections, where the candidates must participate in state primaries to receive delegates to the national convention. Ferrell remarks that Truman was a product of the boss system in Kansas City, and that he was nominated in 1944 by the boss system[36] who had made it clear to Roosevelt that Wallace was unacceptable to them.[27]

Ferrell also writes that Roosevelt was disingenuous, in particular towards Byrnes, and "elevated untruthfulness to a high art." Roosevelt used subordinates for tasks that were unpleasant, like telling Byrnes and Wallace to withdraw. The Roosevelt administration, writes Ferrell, saw many examples of the president welcoming enemies into the oval office, charming them, and giving every evidence of friendship, whereupon they later received unmistakable evidence of where they stood within the administration.[37] Edward Flynn, however, believed that because of his poor health Roosevelt was reluctant to get involved in a quarrel: "I believe that in order to rid himself of distress or strife and rather than argue, he permitted all aspirants for the nomination to believe it would be an open convention."[38]

Ferrell asks himself if Truman, who appeared to gain the office without the effort, in reality was playing a calculated and sly game. Ferrell claims that everything suggests that Truman was trying to achieve the office he insisted he was not interested in. He would have been a strange politician otherwise, according to Ferrell. Roosevelt disliked ambitious people, and Truman knew this, so it was probably an advantage to be humble and deny he was a candidate.[39]

As a border state senator and a political moderate compared with the liberal Wallace and the conservative Byrnes, Truman was humorously dubbed the "Missouri compromise." The liberal group of the party was disappointed with Truman's nomination. Some newspapers falsely claimed that he had been a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Additionally, he was criticized for having his wife Bess on the payroll. However, these controversies had no impact.[7] Few Americans wanted to change their leadership as the Second World War was still going on, so Roosevelt and Truman easily defeated the Republican nominee Thomas E. Dewey and his running mate John W. Bricker. On January 20, 1945, Truman was sworn in as Vice President of the United States. He eventually held the job for just 82 days. On April 12, 1945, he succeeded to the presidency on Roosevelt's death, just as the Democratic leaders had thought about.

Historical comparisons have been drawn between the 1944 vice presidential selection and the 2020 Democratic Party presidential primaries. In the 2020 primaries, progressive Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont was the clear frontrunner in a crowded field of candidates, but most of the candidates dropped out and endorsed former Vice President and former Senator Joe Biden of Delaware, giving Biden a decisive victory over Sanders.[40] The "Stop Sanders"[41] movement has been compared with the anti-Wallace movement.

Notes

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, preface, page x.

- ↑ "Here Is How Vice President Race Stands". St. Petersburg Times. St. Petersburg, Florida. Associated Press. July 20, 1944. p. 3. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ↑ "An Editorial: Yesterday's Defeat, Tomorrow's Hope". St. Petersburg Times. St. Petersburg, Florida. July 22, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- 1 2 Ferrell, Harry S. Truman: a Life, page 163.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 4-6.

- ↑ Ferrell, Harry S. Truman: a life, page 164.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Harry S. Truman, 34th Vice President (1945)", U.S. Senate.

- ↑ Ferrell, Harry S. Truman: a Life, page 164.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 12-13.

- ↑ "SC Governors – James Francis Byrnes, 1951-1955". SCIWay. South Carolina Government. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ↑ Lubell, Samuel (1956). The Future of American Politics (2nd ed.). Anchor Press. p. 21. OL 6193934M.

- ↑ "U.S. Senate: Harry S. Truman, 34th Vice President (1945)". Senate.gov. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, page 14.

- ↑ Ferrell, Harry S. Truman: a Life, page 165.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 25, 28-29.

- ↑ McCullough, pages 306-307; "William O. Douglas 'Political Ambitions' and the 1944 Vice-Presidential Nomination: A Reinterpretation."

- ↑ Conrad Black, Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Champion of Freedom (2003), ISBN 1-58648-184-3, page 971.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 82-83, 120n. Years later Hannegan's son William P. Hannegan visited the Truman library in Independence. The retired president asked if William's mother had the letter. He wanted them to look for it. (Ibid).

- ↑ Murphy, Bruce Allen. Wild Bill: The Legend and Life of William O. Douglas. New York: Random House, 2003. ISBN 0-394-57628-4. pg. 9 of photographs between pages 366 and 367

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 36-; Ferrell, Harry S. Truman: a Life, pages 166-167; Arnold A. Offner, Another Such Victory: President Truman and the Cold War, 1945-1953,page 15.

- ↑ Tom Robbins, "SIDNEY HILLMAN CONSTRUCTIVE COOPERATION", Daily News, May 4, 1999; "End of Strife", Time, 22 July 1946; Marc Karson, "Labor Will Rule: Sidney Hillman and the Rise of American Labor." - book reviews, The Progressive, June 1994.

- ↑ McCullough; Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 74-75, 82.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 43-44.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, page 47.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, page 50.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 44-45, 54; Ferrell, Harry S. Truman: a Life, page 167.

- 1 2 3 Gunther, John (1950). Roosevelt in Retrospect. Harper & Brothers. pp. 349–350.

- ↑ Ferrell, Harry S. Truman: a Life, page 167; Choosing Truman, page 53.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 50-52.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, page 61.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 61-62; Ferrell, Harry S. Truman: a Life, page 170

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 78, 118n.

- ↑ "Oral History Interview with David L. Lawrence", trumanlibrary.org

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 85-86.

- ↑ "Oliver Stone's Untold History of the United States", Hour 2

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 90-91.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, pages 91-92.

- ↑ Jean Edward Smith, FDR (2006), page 619.

- ↑ Ferrell, Choosing Truman, page 93.

- ↑ "Op-Ed: How Democrats dealt with the Bernie Sanders of 1944". Los Angeles Times. March 8, 2020.

- ↑ "The Stop Sanders movement has gone public". CNN. March 2, 2020.

References

- Robert H. Ferrell, Harry S. Truman: A Life (1995), ISBN 0-8262-1050-3.

- David McCullough, Truman (1992), ISBN 0-671-45654-7.

- Robert H. Ferrell, Choosing Truman: The Democratic Convention of 1944 (1994), Columbia: University of Missouri Press, ISBN 0-8262-1308-1.

- Heaster, Brenda L. "Who's on Second: The 1944 Democratic Vice Presidential Nomination." Missouri Historical Review 80.2 (1986): 156-175.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)