| |

Shown within Turkey | |

| Location | Çorum Province, Turkey |

|---|---|

| Region | Anatolia |

| Coordinates | 40°15′18.03″N 35°14′9.70″E / 40.2550083°N 35.2360278°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Cultures | Hittite |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

Sapinuwa (sometimes Shapinuwa; Hittite: Šapinuwa) was a Bronze Age Hittite city at the location of modern Ortaköy in the province Çorum in Turkey about 70 kilometers east of the Hittite capital of Hattusa. It was one of the major Hittite religious and administrative centres, a military base and an occasional residence of several Hittite kings. The palace at Sapinuwa is discussed in several texts from Hattusa.

Digs

Ortaköy was identified as the site of ancient Sapinuwa after a local farmer contacted Çorum Museum; he found two clay cuneiform tablets in his field. This led to a survey conducted in 1989, and more discoveries.[1]

Ankara University quickly obtained permission from the Ministry of Culture to begin excavation. This commenced in the following year, in 1990, under the leadership of Aygül and Mustafa Süel, and has continued since.

Building A was excavated first, and then Building B in 1995. The building with the Yazılıkaya-style orthostate and 14th century BC charcoal was excavated after 2000. Aygül Süel has been the head of excavations at this site from 1996 onward.

In the first excavated region was a Cyclopean-walled building dubbed "Building A". Building A has yielded 5000 tablets and fragments, dated to the time of Hittite ruler Tudhaliya II (c. 1360 – 1344 BC). They were stored in three separate archives on an upper floor, which collapsed when the building was burnt.

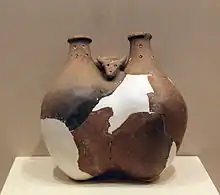

At Kadilar Hoyuk, 150 meters southeast of Building A, "Building B" has proven to be a depot filled with earthenware jars. Another building features an "orthostat that looks like the relief of Tudhaliyas at Yazilikaya".

Findings

The fire which destroyed Sapinuwa also damaged its archive. Most of the tablets are fragmentary, and must be pieced together before interpretation and translation.[2]

Identification of the site as Sapinuwa[3] immediately corrected a misunderstanding in Hittite geography. Due to the archives so far discovered at Hattusas, Sapinuwa had been thought to be a primarily Hurri-influenced city. Scholars of the Hattusas archive therefore positioned Sapinuwa to the southeast of Hattusa. Now Sapinuwa (and therefore the cities associated with it) are known to be to Hattusas's northeast.

The Building A tablets are mostly in Hittite (1500); but also in Hurrian (600), "Hitto-Hurrian", Akkadian, and Hattian.[4] In addition, there are bilingual texts, not heretofore known, in Hittite / Hattian and in Hittite / Hurrian; vocabulary lists in Hittite / Sumerian / Akkadian; and seal impressions in Hieroglyphic Luwian. The Hittite texts include many letters; Hurrian was mostly used for itkalzi (purification) rituals.[4] Several of the letters corresponded with those mentioned in the Maşat Höyük archive. The dialect of Hittite in that correspondence was Middle Hittite, but the site was in use for centuries afterward.[5][6]

The first English-language publication from the excavation was by Aygul Süel, 2002.[7] As of 2014,[8] the archive had not been published. The first English-language publication of any text, a fragmentary vocabulary text listing useful plants, perhaps an advanced school tablet of the 14th century BCE, along with further discussion of the site, appeared in Aygul Süel and Oguz Soysal, "A Practical Vocabulary from Ortakoy";[9] also published is a letter from a queen.[10]

History

The site is divided into an Upper and a Lower City. The latter is divided into two main districts: the Ağılönü region and Tepelerarası; they are separated by a stream which flows through the area.[11]

According to Erdal Atak,

- "The strategic location of Shapinuwa is very important. The mountains surrounding the city, the plateau ascending in terraces on the Amasya Plain, and the fortification facilities starting as far as 5 km enable the city to be easily defendable. Since the city has a key location in between Alaca and Amasya plains, as long as the city, which is two-days distance from Hattusas, stands still, the roads to Bogazkoy-Hattusas are under control. As well as there are traces of military and religious architecture of the upper city on the hills to the west, the need for water and timber were being supplied from these hills."[12]

Northeast of Building D in the Tepelerarası district there is located Area G. A workshop has been uncovered here, featuring finds of intricately carved moulds. These moulds were used for fine silver work; large amounts of obsidian were also found nearby.

These finds date to the end of the Middle Hittite period; this was the time of Tudhaliya II (also known as Tudhaliya III according to some scholars).[11]

This Tudhaliya II also had a Hurrian name Tasmi-Sarri, in common with many other Hittite kings of that time, who also had Hurrian names. His queen was Tadu-Heba, which is also a Hurrian name. Their wedding ceremony is mentioned in many tablets from Sapinuwa, as well as from Hattusa.[13]

Sapinuwa is where Tudhaliya II resided for much of his reign, and many cuneiform tablets mentioning him were found, including international treaties.

This was the time known in literature as ‘concentric invasions’, when the Hittite state was besieged by many enemies on all sides.

At that time, the Kaskans repeatedly invaded Hittite territory. They also probably sacked the capital Hattusa, after which the court moved to Sapinuwa. A destruction of the capital, however, is neither archaeologically proven nor mentioned in contemporary reports.[14]

Nevertheless, Sapinuwa was burned down, after which the court moved to Samuha. Other Hittite cities in the area, such as Tapikka and Sarissa, also suffered destruction at this time.

It is at this time of Hittite weakness that Arzawa in western Anatolia rose to international prominence reflected in the Amarna letters of Amenhotep III. These letters used Hittite language.

Suppiluliuma I was the son of Tudhaliya II, and both of them spent much time fighting the Kaskans, as well as the Hayasans and Arzawa.[15]

Role of Hattians

The Hittites commonly invoked the storm god of Sapinuwa alongside the storm god of Nerik. Given that Hattusa was to the south and Nerik likely further north, both of which had initially been Hattic speaking; that the Hattic language is found in the Sapinuwa archive alongside an apparent paucity of the Palaic language; and that the name of the city makes sense in Hattic as a theophoric (sapi "god", Sapinuwa "[land] of the god"), it is likely that Hattians founded Sapinuwa as well.

It is generally believed that it was Hattusili I who destroyed Nerik in the mid to late 17th century BCE.[16] So it's possible that the Nesite-speaking people would have taken over Sapinuwa at the same time as well.

The Hittites' enemy at that frontier during the 15th century BC were the Kaskas.

Oguz Soysal writes: "The excavators of Ortaköy believe that this city was a second capital of the Hittites or a royal residence, for a specific period, namely during the Middle Hittite Kingdom, ca. late 15th century B.C."[6] However, "[m]ost of the epigraphic finds are dated to the last phase of the Hittite Middle Kingdom (ca. 1400-1380 B.C.)", contemporary with Tudhaliya I and the archive at Maşat Höyük.

It is possible that the Kaskas were responsible for the burnings that turned some of the building materials into coal in the 14th century BC. The Hittite court then moved away to Samuha.

See also

References

- ↑ Şapinuwa (2016) turkisharchaeonews.net

- ↑ Süel (2002), pp. 157–166, 163.

- ↑ Aygul Süel, M. Süel (K. Kamborian, tr.) "Sapinuwa : Découverte d'une ville hittite", Archaeologia (1997:68-74).

- 1 2 Süel (2002), p. 163.

- ↑ Süel (2002), p. 165.

- 1 2 Oguz Soysal, on behalf of the Ortaköy-Sapinuwa Epigraphical Research project, summarizes the contents that the documents include as "letters, lists of persons, tablet-catalogs, oracular texts, prayers, rituals and festival descriptions". Description of the Ortaköy-Sapinuwa Epigraphical Research project Archived August 20, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Süel (2002); see review by Billie Jean Collins in Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 337 (February 2005):96), called the only English-language report to date.

- ↑ Mark Weeden (2014). "State Correspondence in the Hittite World". In Karen Radner (ed.). State Correspondence in the Ancient World. Oxford University Press. pp. 32–63, 215–222. Also Trevor Bryce (2006). "Preface". The Kingdom of the Hittites, new ed. Oxford University Press. pp. xvii. ISBN 978-0-19-928132-9.

- ↑ Süel, Aygul; Soysal, Oguz (2003). "A Practical Vocabulary from Ortakoy". In G. Beckman; R. Beal; G. McMahon (eds.). Hittite Studies in Honor of Harry A. Hoffner Jr. on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. pp. 349–365.

- ↑ Süel (2002), p. 158, figure 1

- 1 2 Süel, A. and Weeden, M. (2019), A Silver Signet-Ring from Ortaköy-Sapinuwa. in N. Bolatti Guzzo and P. Taracha (eds) ‘And I knew 12 Languages.’ A Tribute to Massimo Poetto on the Occasion of his 70th Birthday. Warsaw: Agade. Pp. 661-668

- ↑ Erdal Atak, Sapinuva

- ↑ Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, D. T. Potts, eds (2022), The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC. Oxford University Press - Dassow, p.570

- ↑ Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, D. T. Potts, eds (2022), The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC. Oxford University Press - Dassow, p.571

- ↑ Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, D. T. Potts, eds (2022), The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume III: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC. Oxford University Press - Dassow, p.574

- ↑ Herrmann, Virginia, et al., (2020). "Iron Age Urbanization and Middle Bronze Age Networks at Zincirli Höyük: Recent Results from the Chicago-Tübingen Excavations", in ASOR 2020 Annual Meeting.

Sources

- Süel, Aygul (2002). "Ortaköy-Sapinuwa". In Hans Gustav Güterbock; K. Aslihan Yener; Harry A. Hoffner; Simrit Dhesi (eds.). Recent developments in Hittite archaeology and history. Eisenbrauns. pp. 157–166.